"The Old Theatre Near the Capital": Archaeological and Documentary Investigations into the Site of the Third Theatre

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1676

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2003

"The Old Theatre Near the Capital":

Archaeological and Documentary

Investigations into the Site

of the Third Theatre

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

April 1998

Table of Contents

| Page | |

| List of Figures | ii |

| Acknowledgments | iii |

| Chapter 1: Introduction | 1 |

| Chapter 2: Theatre Building in the American Colonies | 3 |

| Williamsburg's Second Theatre (1751-1755) | 6 |

| Williamsburg's Third Theatre (October 1760-June 1780) | 9 |

| Chapter 3: Previous Archaeology | 11 |

| Chapter 4: 1996 Archaeological Results | 13 |

| Chapter 5: 1997-98 Archaeological Results | 17 |

| Chapter 6: Interpretations | 23 |

| Chapter 7: Conclusions and Recommendations | 26 |

| References Cited | 27 |

| Page | |

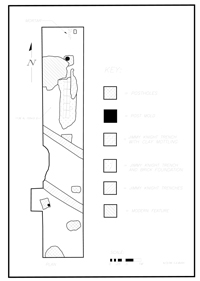

| 1. Location of excavation area | 1 |

| 2. 1731 Hogarth painting entitled "The Indian Emperor" | 4 |

| 3. 1733 Hograth etching entitled "The Laughing Audience" | 5 |

| 4. Plan showing 30 x 35 foot area on the Davenport/Draper lot mentioned in 1780 deed. | 10 |

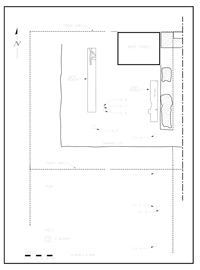

| 5. Plan view and profile of pit feature and foundations uncovered in 1942 | 11 |

| 6. Plan view of west trench | 13 |

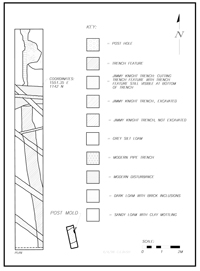

| 7. W. Davis wine bottle seal | 13 |

| 8. Plan view of east trench | 14 |

| 9. Location of test units, Moir lot | 14 |

| 10. Location of test units, Davenport/Draper lot | 14 |

| 11. Plan view of features in northwestern corner of Davenport/Draper lot | 15 |

| 12. Plan view of large postholes and molds on Davenport/Draper lot | 16 |

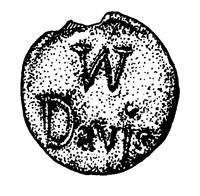

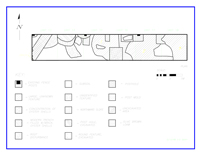

| 13. Plan view of 1997-98 excavations on Davenport/Draper lot | 17 |

| 14. Plan view of structural posts, 1997/98 excavations | 18 |

| 15. Plan view of units on north edge of Davenport/Draper lot | 20 |

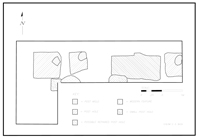

| 16. Plan view of brick foundation, 1997/98 excavations | 21 |

| 17. Plan view of bricks recovered in 1942 and 1997/98 excavations | 21 |

| 18. Plan view of possible post structure | 24 |

| 19. Plan view of possible brick foundation with northward return | 24 |

| 20. Plan view of possible brick foundation with southward return | 24 |

| 21. Area recommended to be cleared for further excavation | 26 |

Acknowledgments

Without the help of a number of people, this project would not have been successful. The field crew, which changed at various times, included Whitney Battle, Elizabeth Gallucci, Elizabeth Grzymala, Gary Robinson, Ashley Tupper, Josh Beatty, Lucie Vinciguerra, R. Grant Gilmore and Lily Richards. Lab Technicians Cheryl Beck and Susan Wiard processed the artifacts, Heather Harvey illustrated the wine bottle seal in Figure 7, and David Muraca supervised the project. Charles Bush, who served as theatre consultant, drafted all the 1996 AutoCAD maps and Lucie Vinciguerra drafted the 1997-98 maps contained in this report.

Chapter 1:

Introduction

The 'old Theatre near the Capital'...was so far old, that the walls were well browned by time, and the shutters to the windows of a pleasant neutral tint between rust and dust colored.... Within, the play-house presented a somewhat more attractive appearance. There was 'box,' 'pit,' and 'gallery,' as in our own day; and the relative prices were arranged in much the same manner.(Cooke 1854:44)

Interest in Williamsburg's three colonial theatres has not only inspired novelists such as John Esten Cooke, whose fictional description is quoted above, but also several generations of Foundation researchers. In fact, Williamsburg was the home to British North America's first theatre, built in 1716. Thirty-six years later, in 1752, Williamsburg had another first, by hosting the Hallam Company. This was the first professional company of English actors and actresses to perform in the colonies.

Intrigued by Williamsburg's place in theatre history, attempts to reconstruct one of Williamsburg's three theatres were undertaken in the 1930s, when buildings related to the old colonial capital were being restored and rebuilt. The Reverend Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin was interested in reconstructing the First Playhouse of 1716, but actual attempts were not undertaken until the 1940s.

Ironically, archaeology resulted in the abandonment of the first attempt at reconstruction. In 1947, the suspected remains of the First Theatre were uncovered by architect James Knight south of the Brush-Everard House in the northwest part of town. Based on historical research, it was thought that the theatre ran parallel to Palace Street. Unfortunately, the uncovered foundations ran perpendicular to this street. Since planners were

Figure 1. Location of excavation area.

2

unable to reconcile this discrepancy, the project was abandoned. In the 1950s, Colonial Williamsburg again considered reconstructing the First Theatre, but concerns about the building's design and safeguards mandated by modern laws forced the project to be put on hold (Bush 1995).

Figure 1. Location of excavation area.

2

unable to reconcile this discrepancy, the project was abandoned. In the 1950s, Colonial Williamsburg again considered reconstructing the First Theatre, but concerns about the building's design and safeguards mandated by modern laws forced the project to be put on hold (Bush 1995).

Today, nearly forty years later, reconstructing one of Williamsburg's three colonial theatres is a distinct possibility. Although an outdoor stage was reconstructed on the site of the First Theatre (since moved to the site of the third theatre), the lack of substantial documentation has made full reconstruction problematic. More information has survived about the Second Theatre, but it lies partially beneath the reconstructed Christiana Campbell's Tavern.

The site of the Third Theatre, located behind the Capitol, is being considered for reconstruction because of the amount of information known about it as well as its accessibility. The information contained in this report is the result of recent attempts to pinpoint the exact location of the Third Theatre, determine its construction date, and to ascertain its size, layout and fate. Documentary research combined with archaeological excavations has answered some of these questions, but further excavations will no doubt uncover more information about Williamsburg's Third Theatre.

Chapter 2:

Theatre Building in the American Colonies

The history of theatre architecture in the American colonies is largely incomplete. Before 1800, plays were typically performed in temporary or insubstantial structures. The impermanence of these buildings was due mainly to the nomadic tendencies of theatrical companies. It would have been impractical to build substantial theatres for amateur or semi-professional acting companies that traveled from town to town. Even after the arrival of the first professional English acting company in 1752, theater architecture, although slightly improved, was still impermanent in nature. Since few companies could depend on making a living in just one town, they were forced to tour the colonies, performing and erecting theatres where they could. Needless to say, this did not lend itself well to the construction of more permanent playhouses. Not until the 1790s would well-known architects such as James Hoban, who designed the White House, begin to fashion theatres (McNamara 1969). One of the earliest references to a play being performed in the colonies is a 1665 court case. In that year, William Darby and two accomplices from Accomac County, Virginia were charged with illegally presenting a play called Ye Bare and Ye Cubbe. Unfortunately, no information about the play or its location has survived (Young 1973).

Fifty-one years later, in 1716, the first theatre in the English colonies was erected in Williamsburg. In 1947, a brick foundation, which measured 86 feet 6 inches by 30 feet 2¼ inches, was uncovered on the Coleman-Tucker lot on Palace Green. These remains are suspected to be the remnants of the First Theatre (Knight 1947). When converted into a courthouse in 1745, the First Theatre was said to have been weatherboarded and roofed with shingles. It has been assumed that there were few windows and doors in the original structure since five windows and another door were later added (Bullock 1935).

The use of rooms, warehouses, and insubstantial buildings as theatres was not uncommon in the eighteenth century. A 1731 William Hogarth painting depicts a private performance of The Indian Emperor in a large room of a dwelling (Figure 2). In 1735, plays were performed in a Charleston South Carolina courtroom before a theatre opened there a year later. In New York City, plays were performed in the long room of a dwelling in 1739, and in the room of a wooden building in 1750.

Around mid-century in Philadelphia and Annapolis, warehouses were used as temporary theatres. Even after the Revolutionary War, when theatre architecture was improving, plays in the outlying areas were still performed in temporary or insubstantial structures (McNamara 1969).

Throughout the eighteenth century, buildings originally devoted to the performance of plays were constructed, but most appear to have been poorly built. A 1766 theatre riot destroyed the Chapel Street playhouse in New York City, and a storm blew down the theatre in Newport, Rhode Island, which was described as a "slight wooden structure, hastily erected" (McNamara 1969:48). The Second Theatre, built in Williamsburg in 1751,

4

Figure 2. 1731 Hogarth painting entitled "The Indian Emperor."

was constructed in approximately eight weeks, suggesting it was also hastily erected (Stephenson 1946b). The 1766 Southwark Theatre in Philadelphia was said to have been "built in too great a hurry" because it "leaked a good deal, and it was scarcely ever dry" (McNamara 1969:54-55). Although the Southwark Theatre was one of the finest playhouses yet built in the colonies, it was described in 1786 as "an ugly ill-contrived affair inside and outside" (McNamara 1969:54-55). Painted red, it stood two-and-a-half stories tall with a brick first story. George Seilhamer, a nineteenth-century theatre historian, described it by stating:

Figure 2. 1731 Hogarth painting entitled "The Indian Emperor."

was constructed in approximately eight weeks, suggesting it was also hastily erected (Stephenson 1946b). The 1766 Southwark Theatre in Philadelphia was said to have been "built in too great a hurry" because it "leaked a good deal, and it was scarcely ever dry" (McNamara 1969:54-55). Although the Southwark Theatre was one of the finest playhouses yet built in the colonies, it was described in 1786 as "an ugly ill-contrived affair inside and outside" (McNamara 1969:54-55). Painted red, it stood two-and-a-half stories tall with a brick first story. George Seilhamer, a nineteenth-century theatre historian, described it by stating:

The brick work was rude but strong, and the wooden part of the building rough and primitive. The whole was painted glaring red. The stage was lighted by plain oil lamps, without glasses, and the view from the boxes was intercepted by large wooden pillars supporting the upper tier and the roof.(Young 1973:18)

Little documentation about the exterior or interior appearance of early American theatres has survived. In the 1750s, after the arrival of Lewis Hallam's professional company of actors, Hallam began to alter and construct playhouses that contained differential seating. The wealthy sat in side boxes, the middling classes sat on backless benches in the pit in front of the stage, and the lower classes sat on benches upstairs in the gallery. The pit or main floor of early theatres was frequently sunk below ground level, sloping from the rear of the auditorium toward the stage (McNamara 1969:24). Candles and oil lamps provided lighting and spikes were sometimes placed around the outer edge of the stage in order to protect the performers from unruly audience members. A 1752 account documented the presence of spikes at Williamsburg's Second Theatre. In that year, three men

5

Figure 3. 1733 Hogarth etching entitled "The Laughing Audience."

Figure 3. 1733 Hogarth etching entitled "The Laughing Audience."

violently assaulted and wounded PATRICK MALONEY, Servant to the company, by knocking him down, and throwing him upon the Iron-Spikes, one of which run into his leg, by which he hung for a consideredable Time.(Stephenson 1946b:13)

A 1733 etching by William Hograth entitled The Laughing Audience shows the internal arrangement of an eighteenth-century English playhouse (Figure 3). The gentry can be seen in the boxes entertaining their lady friends, while the middling classes, below in the pit, laugh at the performance. A partition covered with spikes separates the audience from the orchestra and the stage (Antal 1962).

There are two surviving accounts of pre-Revolutionary War theatres that reveal insight into their dimensions. In 1764, the New York Gazette ran an advertisement which indicated that the Chapel Street Theatre was for rent. The ad stated that it was "very convenient for a Store, being upwards of 90 feet in Length, nigh 40 feet wide" (McNamara 1969:48). The Southwark Theatre, constructed just outside of Philadelphia in 1766, was said to have been 95 feet long and 50 feet wide, and the suspected remains of the First Theatre in Williamsburg measured approximately 86 feet by 30 feet. After the Revolutionary War, long narrow theatres continued to be constructed. The Charleston Theatre, for example, measured 125 feet by 56 feet, while the theatres in Providence and Petersburg measured 81 feet by 50 feet and 85 feet by 45 feet, respectively (McNamara 1969).

6From the construction of the First Theatre in Williamsburg in 1716 to the end of the eighteenth century, theatre architecture was, by most accounts, modest. The use of rooms, warehouses, and "hastily erected" buildings to perform plays was very common before the arrival of Lewis Hallam's professional company of actors in 1752. Although Hallam and his successor David Douglas built and altered theatres to make them "regular" (containing boxes, pits and galleries), the structures themselves remained relatively insubstantial.

WILLIAMSBURG'S SECOND THEATRE1 (1751-1755)

On August 27, 1751, a week before purchasing lots 21 and 22 from Benjamin Waller, Alexander Finnie placed an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette to notify the public that a Company of Comedians, then in New York, intended to give performances in Williamsburg. He stated, "There being no Room suitable for a Play-House, 'tis propos'd that a THEATRE shall be built by Way of Subscription." Each subscriber who advanced a pistole would be entitled to a box ticket for the first night's performance. A notation at the bottom of the advertisement declared that "The House [is] to be completed by October court" (Hunter, August 29, 1751). Interest in building a theatre came approximately six years after Williamsburg's First Theatre was turned over to city officials for use as a hustings court. The Company of Comedians included at least two renowned actors and producers, Walter Murray and Thomas Kean (Farish 1940:1; York County Deed Book 5:154-155; Stephenson 1946a: 7).

On September 26, 1751, only twenty-four days after Finnie purchased lots 21 and 22, it was announced that "King Richard the Third" would be performed in the "new Theatre" on October 21. Tickets were available for seats in the boxes, pit and gallery (Hunter, September 26 and October 17, 1751). A week after the Company of Comedians announced the opening of their first play, they advertised for investors because they had been "at a greater Expense than they at first expected in erecting a Theatre" and also because they needed "to procure proper Scenes and Dresses." They asked those who loved the theatre "to assist them, by way of subscription, for the Payment of the House and Lots" (Hunter, October 24, 1751). Unless it was recorded in the General Court, the absence of a deed from Finnie to the Company of Comedians raises the possibility that the actors were leasing the property from him or had an option to buy it. On April 17, 1752, the public was advised that The Constant Couple or A Trip to the Jubilee would be presented "at the new Theatre in Williamsburg" (Hunter, April 17, 1752). Two weeks later, the Company of Comedians announced that they would be giving performances at Hobb's Hole (Tappahannock) from May 10 through 14 and would be in Fredericksburg in time for the June Fair (Hunter, April 30, 1752).

In June 1752, Lewis Hallam of Goodmansfields, London, and his company of actors arrived at Yorktown aboard the Laughing Sally and proceeded to Williamsburg. They 7 reportedly came equipped with scenery, costumes and decorations that were "all entirely new, extremely rich and finished in the highest Taste, the Scenes being painted by the best Hands in London" (Hunter, June 12 and July 3, 1752). On August 8, 1752, Hallam purchased lots 21 and 22 from Alexander Finnie for 150 pounds 10 shillings. Finnie, as grantor, noted in his deed that he had bought the lots from Benjamin Waller on September 2, 1751, and that he and his wife Sarah were relinquishing all interest "in the said Play House and lotts of land," which lay "on the East side of the Eastern Street of the City of Williamsburgh." At the time the transaction occurred, Hallam signed a memorandum stating that Finnie was not liable to him, if he (Hallam) "or his assigns do not perform and strictly comply with the proviso and condition in the within mentioned indenture from the sd. Benjamin Waller ... to the sd. Alexander Finnie" (York County Deed Book 5:497). This "proviso or condition" apparently referred to Waller's requirement that Finne, within three years, erect a solitary structure that measured at least 20 feet by 50 feet with brick chimneys or a 16 foot by 20 foot building upon each lot. If Finnie or his assignees failed to fulfill Waller's development requirements within the prescribed time, the lots would revert back to Waller. Thus, Hallam agreed to free Finnie from Waller's building requirements. Finnie and John Hyndman, on the other hand, signed an agreement whereby they became bound to Hallam for 301 pounds, if the August 8, 1752, deed were to prove invalid (York County Deed Book 5:499).

On August 21, 1752, Lewis Hallam announced that he had "with great Expense, entirely altered the Play-House ... to a regular Theatre, fit for the Reception of Ladies and Gentlemen." An announcement that followed a week later indicated that the remodeled theatre not only had a pit, boxes, and a gallery, but also a balcony. The Merchant of Venice and The Anatomist or Sham Doctor were performed in Hallam's theatre on September 5, 1752, and Othello was presented on November 9 (Hunter, August 21, August 28, and November 17, 1752).

On November 14, 1752, Dr. George Gilmer2 informed a correspondent that the governor was opposed to Lewis Hallam and his "Company of Strollers" on account of their "loose behavior." He added, however, that public sentiment had persuaded the governor to give Hallam's group permission to perform. Gilmer said that Hallam "purchased Finnie's theatre, enlarged it mostly lining it, so altering it to make it a regular house." He indicated that performances given by Hallam's Company were well received and that they sometimes earned as much as 300 pounds a night. Even so, Gilmer stated that "Never were debts worse paid" (Farish 1940:4-5).

On May 19, 1753, Lewis Hallam of Williamsburg deeded lots 21 and 22 "whereon the Play House now stands" to John Stretch and Edward Charlton in exchange for five shillings. Hallam noted that certain members of his acting company (Charles Bell, William Rigby, William Adcock and John Singleton) were indebted to Stretch 8 and Charlton, and that action against them was pending in Williamsburg's Hustings Court. He added that the four men agreed to repay Stretch and Charlton by October 20, whereupon Hallam's deed with the grantees would become invalid (York County Deed Book 5:553-554). This transaction indicated that Lewis Hallam used the playhouse and the lots upon which it stood as collateral to secure his performers' debts. Doing so would have kept the actors out of jail, enabling them to perform. Lewis Hallam and his acting company departed Williamsburg in the fall, as they were scheduled to appear in New York on December 13, 1753 (Stephenson 1946b:13).3 Thus, Hallam's theatre and lots were left in the hands of John Stretch and Edward Charlton.

Between September 2 and 16, 1754, lots 21 and 22 reverted to Benjamin Waller, who, on September 16, conveyed them to printer John Stretch for 10 pounds 15 shillings. Waller's deed stated that he had previously sold the lots to Alexander Finnie, who failed to develop them in a prescribed manner within three years. Waller reiterated his building requirements and noted that Stretch's failure to comply would result in forfeiture (York County Deed Book 5:627-628). However, no reference was made to the theatre or the fact that Finnie had conveyed the lots to Lewis Hallam, who had assigned them to Stretch and Charlton. The Theatre was in existence in October 1755, when an exhibition called The Microcosm, or The World in Miniature was "to be seen and heard at the late Play-House" (Parks, October 10, 1755).

On April 22, 1757, when John Stretch deeded lots 21 and 22 in back to Alexander Finnie, he cited the September 1754 date upon which he had purchased them from Benjamin Waller. As Stretch conferred fee simple (outright) ownership upon Finnie and made no reference to Waller's building requirements, those conditions had most likely been met. Yet, approximately five months remained of the three years Stretch had to develop the property. When he purchased the lots, Finnie mortgaged them back to John Stretch, whom he agreed to pay an annuity of 40 pounds sterling for life, based upon the exchange rate in London (York County Deed Book 6:93). Despite these arrangements, on December 15, 1757, Finnie sold lots 21 and 22 to Nathaniel Walthoe for 450 pounds, noting that he had purchased them from John Stretch (York County Deed Book 6:112-113).4 Court documents, dating to the 1760s, revealed that Finnie's obligation to pay John Stretch an annuity was on-going, despite his sale of the lots (York County Land Causes 1746-1769:153-155).

Although it is certain that the Second Theatre was in existence in October 1755, when The Microcosm was on display there, by September 1757 it had been replaced by a structure that met Benjamin Waller's specifications for development. On that date, Alexander Finnie acquired an unencumbered title to the two lots. The theatre building might have been razed, dismantled, or simply moved to a new location.

WILLIAMSBURG'S THIRD THEATRE (OCTOBER 1760 - JUNE 1780)

George Washingtons' diaries and ledgers contain entries for "play tickets" he purchased in Williamsburg in 1760 and 1763 (Fitzpatrick 1917:151, 162-165). Although it is uncertain where the theatrical productions he attended were held, they probably were in a theatre, perhaps the one that, only eight years later, was described as "old." Several issues of the Virginia Gazette, from March, April and May 1768, refer to performances given in the "old theatre" near the capitol (Purdie and Dixon, March 31, April 14, May 19, and May 26, 1768). This structure may have been termed "old" because it was built after 1755, when the Finnie-Hallam theatre ceased to exist, or it may have been "old" in another sense: because it included basic structural elements of the Second Theatre that had been moved across the street from Waller subdivision lots 21 and 22.

During 1768, William Page, who took in lodgers, and Thomas Brammer, a merchant, successively rented the Blue Bell (Block 8, Lot 62). Both men described the location of their businesses as "fronting the play house" and "opposite the play-house" (Rind, March 17 and July 28, 1768). In September 1768, gunsmith William Willis, who also occupied part of the Blue Bell lot during Brammer's tenure, informed the public that he had "lately opened shop near the playhouse." In September 1773, when the Blue Bell was offered for sale, it was described as the house in which Mr. Brammer formerly lived, "opposite to the Playhouse" (Purdie and Dixon, September 22, 1768; January 12, 1769; August 30, 1770; September 23, 1773).

In April 1769, Peter Gardner put a set of figures on display "at the theatre," where they were to appear "upon the stage as if alive" (Purdie and Dixon, April 14, 1769). During September 1769, Joseph McAusland announced that he had been using the playhouse as a school for the past six weeks (Purdie and Dixon, September 7, 1769). In 1770, 1771 and 1772, plays were given at the theatre in Williamsburg, where tickets were available for the boxes, pit and gallery (Purdie and Dixon, April 25, October 24, November 7, and November 21, 1771; April 2, April 16, April 23, and November 19, 1772; Stephenson 1946b:20, Illustration #5). According to Hudson Muse, who spent eleven days in Williamsburg during the spring of 1771, theatrical performances were held nightly. He declared that "Miss Hallam was super fine" and that "The house was crowded every night" (Farish 1940:endnotes; Stephenson 1946b:20-21).

The theatre was scheduled to close at the end of the April 1772 court. The announcement of a final performance appeared in the Virginia Gazette on May 7. David Douglas and his American Company left Williamsburg and were not expected to return for several years (Purdie and Dixon, April 9, April 16, April 23, and May 7, 1772). In November 1772, a puppet show and an exhibit entitled A Curious Set of Figurines were held in the theatre (Rind, November 19, 1772).

A 1774 resolution by the Continental Congress to ban "all kinds of gaming," including the exhibitions of shows and plays, probably temporarily put a damper upon interest in the performing arts (Farish 1940:7). However, the theatre building was still standing on July 1, 1775, when John Lockley advertised that he had found a pair of new saddlebags

10

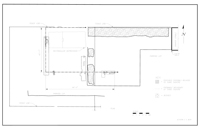

Figure 4. Plan showing 30 x 35 foot area on the Davenport/Draper lot mentioned in 1780 deed.

"near the Playhouse" (Dixon and Hunter, July 1, 1775). How this building was being used during this period is open to conjecture.

Figure 4. Plan showing 30 x 35 foot area on the Davenport/Draper lot mentioned in 1780 deed.

"near the Playhouse" (Dixon and Hunter, July 1, 1775). How this building was being used during this period is open to conjecture.

By June 1780, the theatre was gone. A deed which conveyed a 30 foot by 35 foot parcel in the northwest corner of the Davenport/Draper lot, in Block 8, made reference to the acreage as the land "whereon the Old Play House lately stood" (York County Deed Book 6 [1777-1791]:94). Figure 4 shows this area in detail. On January 26, 1787, James Moir, owner of an adjacent lot, gave the bricks from the old theatre to builder Humphrey Harwood in exchange for some work (Harwood Account Book B:88).

Chapter 3:

Previous Archaeology

In 1942, during the cross-trenching of Block 8, a large rectangular feature and three fragmentary sections of brick foundation were discovered in the rear of the James Moir lot (Figure 5). Architect James Knight suspected that these were remnants of the Third Theatre (Knight 1942:8). The rectangular depression measured 37 feet 7 inches by 16 feet 2 inches and sloped from west to east . The western end of the feature was 2 feet 6 inches below grade, while the eastern end was 4 feet below the surface. A drop of 9 inches was evident in the middle. In the bottom of the pit, at the eastern end, was a 6 foot by 3 foot wooden box, which was covered with a wooden lid. Just to the west of the box was a 2 foot by 6 foot rectangular feature filled mostly with wood chips and shavings. These two unexplained features appeared to be later, possibly modern, intrusions that were unrelated to the original function of the pit.

Figure 5. Plan view and profile pit feature and foundations uncovered in 1942.

Figure 5. Plan view and profile pit feature and foundations uncovered in 1942.

Surrounding this feature on all sides, except the south, were three fragmentary sections of brick foundation. These sections were laid in English bond, one brick wide and deep, forming the shape of a building which measured 44 feet wide and over 33 feet long (Knight 1942). A building of similar size was depicted in this area on the 1781 Frenchman's Map.

Knight proposed that these brick remains were originally part of a small theater building that had later used as a shop or tannery. The pit feature, Knight suggested, may have been related to tanning activities. He interpreted the brickwork to the north and west as examples of early masonry, both built at the same time. The brickwork to the southeast was comprised of different-sized bricks from the other two sections, and, Knight suggested, may have been part of a later addition corresponding to a change in the use of the structure.

The current interpretation of these finds and their possible relationship to the Third Theatre will be explored later in this report in conjunction with the information acquired through present research. Currently the site is covered by a parking lot and landscaping shed.

Chapter 4:

1996 Archaeological Results

In order to find the full dimensions of the building uncovered in 1942, the east and west sections of the foundation were re-exposed in May 1996, with the help of a backhoe. It was hoped that features, such as robber's trenches and postholes not normally observed during cross-trenching would be found. A 40-foot-long trench, excavated over the western section of foundation, uncovered a long linear feature (Figure 6). This feature, which ran north to south at a slight angle, contained eighteenth- and nineteenth-century domestic refuse and was cut by the 1942 cross trenches. The presence of nineteenth-century material ruled out the possibility that this feature was a robber's trench associated with the sale of the theatre bricks in 1787. One notable artifact, a wine bottle seal bearing the name W. Davis, was retrieved from this area (Figure 7). To date, this was only the second seal with this name recovered in Williamsburg's Historic Area. The other was found behind the Golden Ball on Block 17.

Over the eastern section of foundation, a 24½-foot-long trench was excavated, which revealed several small postholes but no robber's trench (Figure 8). A total of six postholes were uncovered which appear to have been part of a fence line that ran north/south. These holes were not excavated; since the overlying layers had been removed during the construction of the parking lot, no date could be assigned to them.

Figure 6. Plan view of west trench.

Figure 6. Plan view of west trench.

Figure 7. W. Davis wine bottle seal shown at actual size. Drawing by Heather Harvey.

Figure 7. W. Davis wine bottle seal shown at actual size. Drawing by Heather Harvey.

Due to the lack of evidence in the two trenches, nine 50-cm-square test units were excavated on the James Moir lot in hopes of discovering the building's continuation (Figure 9). Test Units 2 and 3 uncovered a small posthole most likely related to the fence line discovered in the east trench. Just east of the west trench, shovel tests 6, 7

14

Figure 8. Plan view of east trench.

Figure 8. Plan view of east trench.

Figure 9. Location of test units, Moir lot.

and 8 revealed the presence of a large posthole and mold. Its size and shape suggest that it could have been used to support a structure.

Figure 9. Location of test units, Moir lot.

and 8 revealed the presence of a large posthole and mold. Its size and shape suggest that it could have been used to support a structure.

Since documentary evidence suggested the Theatre extended onto the adjacent Davenport/Draper lot, testing was also undertaken in that area (Figure 10). Three 75-cm-square and fourteen one-meter-square test units were excavated on this lot in order to determine its stratigraphic sequence and to find evidence of the theatre. The stratigraphy consisted of a thin layer of topsoil above a thick, olive brown loam plowed layer. This plowed layer contained a variety of late eighteenth and nineteenth-century domestic artifacts.

Figure 10. Location of test units, Davenport/Draper lot.

Figure 10. Location of test units, Davenport/Draper lot.

In order to discover this building's extension onto the Davenport/Draper lot, six test units were excavated in the

15

Figure 11. Plan view of features in northwestern corner of Davenport/Draper lot.

northwest corner, where the Theatre was said to have "lately stood" (Figure 11). The test units were aligned with a section of foundation discovered in 1942 on the Moir lot. No evidence of the Theatre's presence was discovered, but five postholes and several unknown features were found. The postholes formed an east/west running fence line that appears to have been erected in the early nineteenth century. One of the holes contained domestic refuse which dated no earlier than 1795. Aside from the fence line, three large unknown features were also discovered. Although only partially excavated, the feature in Test Unit 18 dated to the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The other two features were not excavated, but appeared to date earlier than the partially excavated one. Despite the fact that no conclusive evidence of the Theatre was discovered, it still may have existed in this area. The large features and postholes, which appeared to date after the sale of the Theatre's bricks in 1787, could have destroyed any evidence of associated robber's trenches and postholes.

Figure 11. Plan view of features in northwestern corner of Davenport/Draper lot.

northwest corner, where the Theatre was said to have "lately stood" (Figure 11). The test units were aligned with a section of foundation discovered in 1942 on the Moir lot. No evidence of the Theatre's presence was discovered, but five postholes and several unknown features were found. The postholes formed an east/west running fence line that appears to have been erected in the early nineteenth century. One of the holes contained domestic refuse which dated no earlier than 1795. Aside from the fence line, three large unknown features were also discovered. Although only partially excavated, the feature in Test Unit 18 dated to the second quarter of the nineteenth century. The other two features were not excavated, but appeared to date earlier than the partially excavated one. Despite the fact that no conclusive evidence of the Theatre was discovered, it still may have existed in this area. The large features and postholes, which appeared to date after the sale of the Theatre's bricks in 1787, could have destroyed any evidence of associated robber's trenches and postholes.

Since the area in the northwest corner was heavily disturbed by other features, five additional test units were excavated on the Davenport/Draper lot opposite the brick foundation re-exposed in the east trench. In Test Unit 20, a large posthole and mold was discovered which lined up with the one discovered on the Moir lot. In order to determine the presence of additional postholes, three units were excavated east of Test Unit 20 (Figure 12). This resulted in the discovery of four large postholes, one of which appeared to have been replaced with another.

16 Figure 12. Plan view of large postholes and molds on Davenport/Draper lot.

Figure 12. Plan view of large postholes and molds on Davenport/Draper lot.

Including the posthole found on the Moir lot, a total of six large postholes were discovered which formed an east/west line over 59 feet long. Their location, in the middle of the back lots, as well as the fact that they crossed the property line between the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots, suggested that they were not related to a fence line but, instead, may have been used to support a structure.

Chapter 5:

1997-98 Archaeological Results

Between October 1997 and February 1998, archaeologists returned to the site of Williamsburg's Third Theatre to conduct further excavations. These excavations were designed to investigate the east-to-west line of large, potentially structural posts uncovered in 1996 on the Davenport/Draper lot and to determine the relationship these posts may have had with the eighteenth-century theatre. Of larger interest was the potential recovery of the dimensions and floor plan for the theatre (Figure 13).

The initial excavation area included a 124-square-foot area to the east and north of the posts discovered in 1996. In this area, three additional, possibly structural posts and one fence post were recovered. Following these discoveries, the excavation was expanded to the east into the parking lot on the Davenport/Draper lot, where four more fence posts but no structural features were recovered. Finally, the area along the north edge of the Davenport/Draper property was excavated, where the fragmentary remains of an eighteenth-century brick foundation were discovered. These finds will be discussed in greater detail below.

The 1997/98 excavations involved removal of the plowzone in the northwest corner of the Davenport/Draper lot. After the plowzone was removed, the undisturbed subsoil was investigated for eighteenth-century structural features that may relate to the theatre

Figure 13. Plan view of 1997-98 excavations on Davenport/Draper lot.

18

building. The area initially investigated included thirty-eight excavation units, each measuring one meter square. Four new postholes were uncovered along the same east-west axis as the four postholes discovered in 1996. No other features with potentially structural functions were recovered in this initial excavation area.

Figure 13. Plan view of 1997-98 excavations on Davenport/Draper lot.

18

building. The area initially investigated included thirty-eight excavation units, each measuring one meter square. Four new postholes were uncovered along the same east-west axis as the four postholes discovered in 1996. No other features with potentially structural functions were recovered in this initial excavation area.

The first post was 5 feet 3 inches east of the 1996 excavations. It measured 23 inches by 19 inches wide and contained a large, 9 x 8 inch wide post mold. The fill of the posthole was a mix of olive brown sandy loam (Munsell color 2.5Y4/4), yellowish brown clay (10YR5/8), brick flecks and marl. The size of the post mold suggested that this post was potentially structural. The eastern edge of this posthole was cut by another posthole with similar fill. This second post may have been a replacement for the first. The mold of the second was also large, measuring 8 x 8 inches. The second mold was shifted 24 inches east of the first. Again, this may have served as a structural post.

Located 7 feet 2 inches east of the second post mold was another large mold within a very large posthole. This third posthole was 33 inches by 23 inches wide and contained a mixed fill of yellowish brown clay (10YR5/8), olive brown sandy loam (2.5Y4/4), and brick flecks. The post mold, 12 x 12 inches in size, was placed in the northeast corner of the posthole. This third post was also of adequate size to support a structure.

All three of these possibly structural posts were documented but not excavated, thus it is difficult to assign a date to them with certainty. The lack of artifacts visible in the fill suggests that they were placed in the earlier phase of Williamsburg's history, and may relate to the eighteenth-century theatre building (Figure 14).

The size and orientation of these three posts are similar to the five posts uncovered in the 1996 excavation. These previously discovered posts averaged 24 inches across, with molds located in the northeast quadrant of the hole measuring about 8 inches in diameter. Four posts and one replacement post were located in four excavation units adjacent to the west edge of the 1997/98 excavation, and one post was located on the Moir lot. Together, the 1996 and 1997/98 posts form an east/west line over 62 feet long.

Figure 14. Plan view of structural posts, 1997/98 excavations.

Figure 14. Plan view of structural posts, 1997/98 excavations.

A fourth post was uncovered along this same east to west axis. The post mold, situated in the center of the 24 x 24 inch hole, was located 7 feet 2 inches east and 4 inches south of the third post mold. This mold was 8 inches by 5 inches wide, significantly smaller than the three previous molds. This post most likely supported a fence, yet initially this use could not be clearly assigned. It was not excavated.

In order to determine the function of the last post with more certainty, the excavation was expanded toward the east to an area of 28 feet by 21 feet. This area initially contained a gravel-paved parking lot. A Grade-All was used remove the disturbed layers of soil. Several features were uncovered at the subsoil level in this area, but most of these features did not date to the eighteenth century. A modern fence line with intact posts crossed the north and west edges of the stripped area. Also visible were the areas that James Knight excavated in 1942. Near the center of the stripped area was a wide but shallow circular feature that contained late nineteenth-century artifacts.

More significant was the discovery of four posts in line along the south edge of the excavation. These posts appeared to connect with the fence post uncovered to the east in the initial excavation area. The post molds were located at roughly 7 foot 10 inch-intervals. To find the extent of this new line of posts, three additional excavation units, each measuring one meter square, were placed within the parking lot to the east of this stripped area. These units revealed two more posts at similar intervals. The last post was located 7 feet west of the eastern edge of the Davenport/Draper lot. These posts contained molds averaging 6 inches by 6 inches wide within holes averaging 25 inches by 25 inches wide. These posts were in the same line as the structural posts to the west; however, the marked change in post mold size indicated a different function for these posts. It appears that they are too small to be structural.

Overall, seven of the recovered posts appeared to belong to an east-west fence line that ran to the edge of the Davenport/Draper lot, possibly during the eighteenth century. One was discovered in the initial excavation area, four within the stripped parking lot, and two in the excavation units placed in the parking lot. These seven posts form a line of at least 63 feet long situated 44 feet south of the northern lot line for the Davenport/Draper property (see Figure 18).

Further investigation for the Theatre building was directed towards substantiating the placement of the north wall, which had been tentatively assigned to a fragment of a brick foundation that James Knight uncovered in 1942. These bricks were located beneath the north wall of the present landscaping shed. In 1996, archaeologists excavated a series of test units east of the shed. These test units were placed beneath the existing east-west fence that adjoins the landscaping shed with the Davenport/Draper stable. As mentioned previously in this report, features post-dating the theatre were found, which obliterated any evidence of eighteenth-century activities in this area (see Figure 11). In the 1997/98 excavations, another attempt was made to recover a portion of this wall. Three 1 x 1 meter excavation units were placed along the present fence. Again, it was found that post-theatre activities had destroyed any eighteenth-century features in this area (Figure 15).

During February 1998, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation took on the task of replacing the existing fence between the landscaping shed on the Moir lot and the Davenport/

20

Figure 15. Plan view of units on north edge of Davenport/Draper lot.

Draper stable. During this fence replacement, a section of brick was recovered 6 feet 6 inches west of the Davenport/Draper stable. In order to protect the brick foundation, the modern replacement fence was repositioned.

Figure 15. Plan view of units on north edge of Davenport/Draper lot.

Draper stable. During this fence replacement, a section of brick was recovered 6 feet 6 inches west of the Davenport/Draper stable. In order to protect the brick foundation, the modern replacement fence was repositioned.

Archaeologists investigated the extent of this brick, and revealed two sections of a fragmented, eighteenth-century brick foundation along an east-west axis (Figure 16). These two sections were interrupted at each end by modern disturbances and probably were originally connected. The eastern brick cluster was 3 feet 9 inches long, one brick wide and only one course deep. The bricks were irregularly bonded and held in place with shell mortar. Located 5 feet 4 inches to the west was a cluster of bricks 3 feet long, one brick wide and two courses deep. These bricks were also irregularly bonded with shell mortar. The individual bricks ranged in color from yellowish-red to red. The whole bricks measured approximately 8.6 inches long, 4.1 inches wide and 2.6 inches thick. These two sections formed an 11 foot 9 inch-long section of an eighteenth-century brick foundation. A limited search to the east and west along the line of the foundation did not reveal any other intact sections of brick or any evidence of a robber's trench.

During the 1942 excavations, several other sections of eighteenth-century brick foundations had been recovered on the north edges of the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots. These fragmentary remains potentially relate to the newly discovered brick foundation on the north edge of the Davenport/Draper lot (Figure 17).

Located on the Moir lot, were three sections of brick, one on an east axis and two on a north axis. All sections were one brick wide and one brick deep. Knight described the two sections of brick on a north axis as light red in color, in English bond with shell mortar. The bricks on the east axis were located on the north edge of the Moir lot, on the same northern plane as bricks uncovered during this excavation. These bricks were described by Knight as reddish buff in color, with English bond and shell mortar (Knight 1942).

21 Figure 16. Plan view of brick foundation, 1997/98 excavations.

Figure 16. Plan view of brick foundation, 1997/98 excavations.

Figure 17. Plan view of bricks recovered in 1942 and 1997/98 excavations.

Figure 17. Plan view of bricks recovered in 1942 and 1997/98 excavations.

On the northeast corner of the Davenport/Draper lot Knight recovered other brick foundation fragments. The largest fragment was 29 inches long and was situated on a north axis beneath the eastern side of the existing Davenport/Draper stable. Knight described this foundation as badly broken, English bond, one brick wide and two courses deep (Knight 1942). It is possible that this foundation section was the southward return for the newly recovered section of brick. Unfortunately, the Davenport/Draper stable inhibited any further testing in the area between these two sections. At this point, it is not possible to determine if any of these three sections were associated with the foundation recently recovered on the Davenport/Draper lot. Further research may clarify this issue.

In summary, the 1997/98 excavations succeeded in defining two eighteenth-century structural components in the area known to have contained the Theatre. The first was a line of large posts at least 77 feet long and 44 feet south of the north edge of the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots. The second, a fragmentary brick foundation, was located along the north edge of the Davenport/Draper lot. The relationship, if any, that these features may have had to the Theatre will be explored below.

Chapter 6:

Interpretations

As the eighteenth-century capital of Virginia, Williamsburg became the center of cultural activities. One of the things that made it a cultural center was the presence of a theatre. The latest plays, shows, and music from England were performed there for a diverse audience, which helped to narrow the cultural gap between Britain and the colonies. The Third Theatre not only accommodated individuals of notoriety, such as George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, but also people of the lower and middling orders. Although seated according to social position, everyone watched the same performance.

Documentary evidence has shown that the Second Theatre occupied colonial lots 21 and 22. The Third Theatre, which existed throughout the third quarter of the eighteenth century, also spanned two lots. In 1780, a deed conveying a small parcel of land in the northwest corner of the Davenport/Draper lot was referred to as the place where the "old playhouse lately stood." Seven years later, in 1787, James Moir would sell bricks from the Theatre to help pay for repairs to his property.

The integration of the archaeological evidence from the 1996 and 1997/98 field seasons with the historical evidence has produced intriguing but incomplete information. The archaeology revealed the existence of eighteenth-century features of brick and post construction, which spanned both the Moir lot and the northwest corner of the Davenport/Draper lot. These lengthy architectural components were placed in the area where, as historical documents have indicated, the Theatre once stood. These features will require further research to positively associate them, or disassociate them, with the Third Theatre building. The most likely building configurations that can be discerned with the information known at present are depicted in Figures 18, 19 and 20.

The first feature, a series of structural, eighteenth-century posts, was identified in the 1996 excavations and more clearly defined during the 1997/98 season. This series was composed of seven large structural posts and two replacement posts. These posts spanned 62 feet 4 inches along an east-west axis about 44 feet south of the northern edge of the Davenport/Draper lot. The posts were spaced at irregular intervals and may not all be contemporaneous. The largest interval between molds was 7 feet 6 inches, while the smallest was 2 feet. Some of these posts may have formed a structural component of the theater, but which component is unclear. No northward return of posts or any other structural material was recovered perpendicular to this line of large posts. The possibility of a southward return has not yet been investigated.

The documentary evidence has suggested that the Theatre contained brick structural components. This may seem to eliminate the posts as a potential Theatre component; however, a combination brick and post structure, though uncommon in the later eighteenth century, may have been constructed to save costs for the financially strapped theatre company. By most accounts, colonial theatres were insubstantial, hastily erected structures

23

Figure 18. Plan view of possible post structure.

Figure 18. Plan view of possible post structure.

Figure 19. Plan view of possible brick foundations with northward return.

Figure 19. Plan view of possible brick foundations with northward return.

Figure 20. Plan view of possible brick foundations with southward return.

24

which were usually long and narrow. One of the finest theatres in the colonies, Philadelphia's Southwark Theatre, was apparently built too quickly because it leaked a great deal and was described as "ugly" both inside and out. Williamsburg's Second Theatre was built in about eight weeks, and it seems likely that the Third Theatre was also quickly erected, possibly incorporating elements of the former theatre.

Figure 20. Plan view of possible brick foundations with southward return.

24

which were usually long and narrow. One of the finest theatres in the colonies, Philadelphia's Southwark Theatre, was apparently built too quickly because it leaked a great deal and was described as "ugly" both inside and out. Williamsburg's Second Theatre was built in about eight weeks, and it seems likely that the Third Theatre was also quickly erected, possibly incorporating elements of the former theatre.

The second feature with a potential relationship to the Third Theatre was a brick foundation discovered along the north edge of the Davenport/Draper lot. The remains of this foundation were fragmentary and had been disturbed by the occasional replacement of a fence along this same axis. In 1942, James Knight discovered three other sections of brick foundations on the northern end of the Moir lot, and one section near the northeast corner of the Davenport/Draper lot. Any of these sections could potentially connect with the newly uncovered brick foundation. The two mostly likely scenarios are depicted in Figures 19 and 20. These fragments of brick would have formed structures ranging from at least 85 feet to 118 feet in length respectively.

These sizes are comparable to other eighteenth-century theaters in the colonies. The Chapel Street Theatre in New York City, for example, measured approximately 90 feet by 40 feet and the Southwark Theatre in Philadelphia was 95 feet by 50 feet in size. Therefore, the overall extent of the Third Theatre could have exceeded 90 feet in length. Thus the location, materials used and size of the brick foundation on the northern edge of the Davenport/Draper and Moir lots are consistent with the historical documentation of the Third Theatre.

Finally, another feature discovered in 1942 by James Knight may have been related to the Theatre. This feature was a large rectangular depression, 37 feet 7 inches by 16 feet 2 inches, which may have been the "pit." This depression was located in front of the stage and would have usually seated the middling classes. According to theatre historian Brooks McNamara, the "pit" usually sank below ground and sloped down toward the stage (McNamara 1969:24). The rectangular depression uncovered by James Knight extended below ground and sloped from west to east.

Chapter 7:

Conclusions and Recommendations

According to the documentary evidence gathered, the Third Theatre existed on both the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Further excavations are necessary in order to determine if either the eighteenth-century brick or post building elements discovered during the three phases of archaeological testing were indeed part of the Third Theatre.

To begin these excavations, it is recommended that both lots be mechanically stripped down to subsoil in order to reveal possible features. Soil disturbances have occurred on these properties and there is no need to excavate any overlying layers by hand. A large section of the Moir lot is covered by a parking lot and a landscaping shed, which have disturbed the underlying stratigraphy and covered a portion of the brick foundation. The Davenport/Draper lot has been plowed, mixing the layers and artifacts, and a stable in the northeast corner overlies a brick foundation potentially related to the Theatre. Several disturbed or modern components are recommended for removal. These include the area of soil surrounding and between both features on the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots, the existing landscaping shed, the existing Davenport/Draper stable, and the existing northern fence between these two lots (Figure 21).

After clearing the area, the excavation can then be directed towards the investigation of the brick foundation along the northern edge of the Moir and Davenport/Draper lots, and the wooden post remains that span the north sections of both lots. With this investigation, the structural layout and floor plan of the Theatre may be recovered, and the reconstruction of this building may proceed.

Figure 21. Area recommended to be cleared for further excavation.

Figure 21. Area recommended to be cleared for further excavation.

Footnotes

References Cited

- 1962

- Hogarth and his Place in European Art. Basic Books, Inc., New York.

- 1935

- The Playhouse (NB) Historical Report, Block 29 Building 17 A Lot 163-164-169. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1995

- "'all the best Plays, Opera's Farces, and Pantomines' Revival of an old idea: bringing back an 18th-century playhouse in the town where American theatre began." The Colonial Williamsburg Journal.

- 1854

- The Virginia Comedians or Old Days in the Old Dominion. D. Appleton and Company, New York.

- 1775

- Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg. Photostats on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1940a

- Second Theatre (NB), Block 7 Colonial Lots 21 and 22. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1940b

- Capitol Historical Report, Block 8 Building 11. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1917

- George Washington's Accounts of Expenses ... 1775-1783. Houghton-Mifflin, Boston and New York.

- Harwood, Humphrey 1784-1792 Account Books. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1751-1752

- Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg. Photostats on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1942

- George Davenport House Archaeological Report, Block 8 Building 27. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1947

- The Playhouse (First Theatre) Archaeological Report, Block 29 Building 178. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg. 27

- 1969

- The American Playhouse in the Eighteenth Century. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- 1745-1755

- Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg. Photostats on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1766-1778

- Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg. Photostats on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1986

- First Theatre, Block 29, Bldg. 17A (NB), Archaeological Briefing. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1946a

- The First Theatre. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1946b

- Second Theatre Historical Report, Block 7 Lot 21 and 22. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1745-1830

- Deeds, Orders, Wills, Judgments, Land and Personal Property Tax Lists. Microfilm on file, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg

- 1973

- Documents of American Theater History, Volume I: Famous American Playhouses 1716-1899. American Library Association, Chicago.