Peyton Randolph House Architectural Report, Block 28 Building 6Originally entitled: " Building An Image: An Architectural Report on the Peyton Randolph Site"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1542

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

Portrait of Peyton Randolph

Portrait of Peyton Randolph

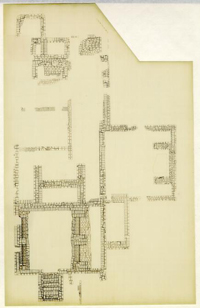

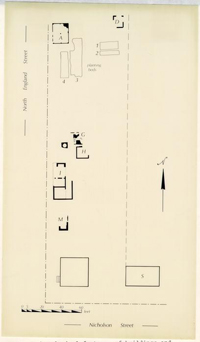

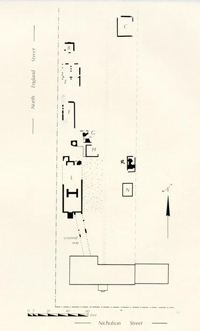

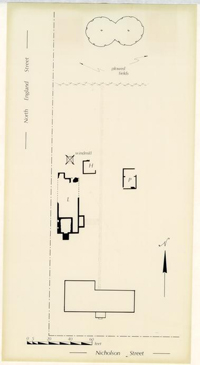

Figure 1 - Site Plan of all excavated features on lot 207, north of the Peyton Randolph House. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 1 - Site Plan of all excavated features on lot 207, north of the Peyton Randolph House. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

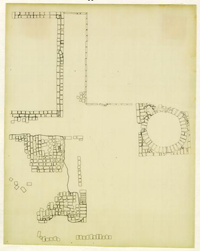

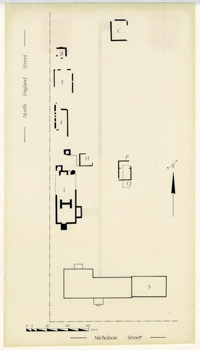

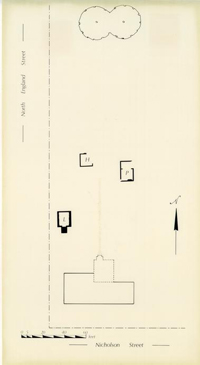

Figure 2 - Archaeological features thought to date to the first period of development. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 2 - Archaeological features thought to date to the first period of development. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

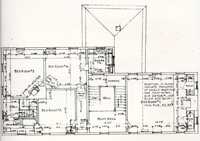

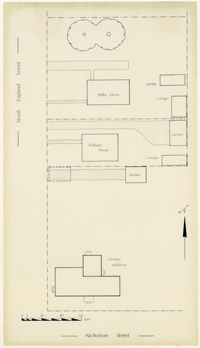

Figure 3 - First Floor Plan, Mount Airy southeast dependency. Measure by Charles Bergengren, S. Allan Chambers, Edward A. Chapell, Willie Graham, Mark Schara and Douglas Taylor. Drawn by Mark Schara and Douglas Taylor, CWF, 1981.

Figure 3 - First Floor Plan, Mount Airy southeast dependency. Measure by Charles Bergengren, S. Allan Chambers, Edward A. Chapell, Willie Graham, Mark Schara and Douglas Taylor. Drawn by Mark Schara and Douglas Taylor, CWF, 1981.

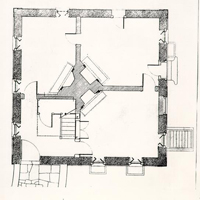

Figure 4 - First-floor plan of Peyton Randolph House as it existed before restoration. Drawn by R. A. W. (probably Richard Walker), CWF, 1938.

Figure 4 - First-floor plan of Peyton Randolph House as it existed before restoration. Drawn by R. A. W. (probably Richard Walker), CWF, 1938.

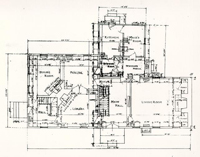

Figure 5 - Second-floor plan of Peyton Randolph House as it existed before restoration. Drawn by R. A. W., CWF, 1938.

Figure 5 - Second-floor plan of Peyton Randolph House as it existed before restoration. Drawn by R. A. W., CWF, 1938.

Figure 6 - Pre-restoration photograph of the south elevation of the first-floor southeast room in oldest section of Peyton Randolph House. Photographer unknown, CWF, circa

1938.

Figure 6 - Pre-restoration photograph of the south elevation of the first-floor southeast room in oldest section of Peyton Randolph House. Photographer unknown, CWF, circa

1938.

Figure 7 - Pre-restoration photograph of north and east wall elevations, first floor northeast room, Peyton Randolph House. Photographer unknown, CWF, circa

1938.

Figure 7 - Pre-restoration photograph of north and east wall elevations, first floor northeast room, Peyton Randolph House. Photographer unknown, CWF, circa

1938.

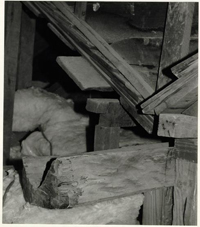

Figure 8 - Tar-lined oak gutters servicing original roof system. Douglas Taylor, CWF, 1982.

Figure 8 - Tar-lined oak gutters servicing original roof system. Douglas Taylor, CWF, 1982.

Figure 9 - Original multi-ridge roof with square-butt shingles. The tarred clapboard and weatherboard wall is coped over the shingles without the use of flashing. Original roof enclosed by period-two roof. Edward A. Chappell, CWF, 1982.

Figure 9 - Original multi-ridge roof with square-butt shingles. The tarred clapboard and weatherboard wall is coped over the shingles without the use of flashing. Original roof enclosed by period-two roof. Edward A. Chappell, CWF, 1982.

Figure 10 - Archaeological drawing of planting beds one and two. Beds were lined with bottle, ceramic and bone fragments, as well as oyster shells. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1983.

Figure 10 - Archaeological drawing of planting beds one and two. Beds were lined with bottle, ceramic and bone fragments, as well as oyster shells. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1983.

Figure 11 - Foundations for Structures J, K, and L. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 11 - Foundations for Structures J, K, and L. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

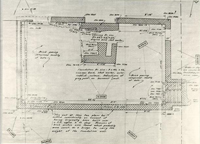

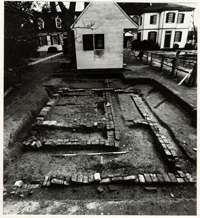

Figure 12 - Foundations for Structure S. Drawn by James Knight, CWF, 1938.

Figure 12 - Foundations for Structure S. Drawn by James Knight, CWF, 1938.

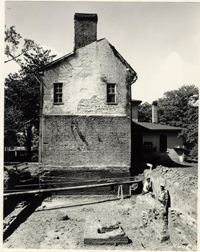

Figure 13 - East facade of period-two addition to Peyton Randolph House looking across the excavated foundations of Structure S. Plaster on wall reveals outline of roof from structure S. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1938.

Figure 13 - East facade of period-two addition to Peyton Randolph House looking across the excavated foundations of Structure S. Plaster on wall reveals outline of roof from structure S. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1938.

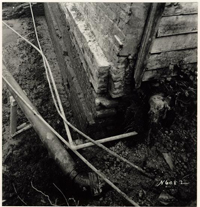

Figure 14 - Northeast corner of Peyton Randolph House showing foundations of Structure S below those of house. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1938.

Figure 14 - Northeast corner of Peyton Randolph House showing foundations of Structure S below those of house. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1938.

Figure 15A - Archaeological features of buildings and planting beds thought to have existed during Sir John Randolph's ownership. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 15A - Archaeological features of buildings and planting beds thought to have existed during Sir John Randolph's ownership. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 15B - Archaeological features thought to have existed circa

1740. The dating of Structure F is highly speculative. Structure E might also have been constructed at mid-century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 15B - Archaeological features thought to have existed circa

1740. The dating of Structure F is highly speculative. Structure E might also have been constructed at mid-century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 16 - Early twentieth-century photograph of the Peyton Randolph House from the southwest. A late-nineteenth century windmill over the well, a smokehouse (Structure H), a dairy (Structure P), the main house, and an unidentified outbuilding located in an unexcavated area are all visible. Photographer unknown, CWF.

Figure 16 - Early twentieth-century photograph of the Peyton Randolph House from the southwest. A late-nineteenth century windmill over the well, a smokehouse (Structure H), a dairy (Structure P), the main house, and an unidentified outbuilding located in an unexcavated area are all visible. Photographer unknown, CWF.

Figure 17 - Archaeological drawing of the appendage to Structure H. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 17 - Archaeological drawing of the appendage to Structure H. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 18 - Archaeological features thought to have existed during Peyton Randolph's ownership of the site. Note that the house was enlarged in this period, and that a substantial amount of rebuilding took place in the yard. Drawn by Natalie Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 18 - Archaeological features thought to have existed during Peyton Randolph's ownership of the site. Note that the house was enlarged in this period, and that a substantial amount of rebuilding took place in the yard. Drawn by Natalie Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 19 - Pre-1870's photograph of the Peyton Randolph House showing an eighteenth or early nineteenth-century porch, the original chimney stack to the house, and the building that served as the kitchen, laundry and servants quarter. Photographer unknown. Copy from CWF Library files.

Figure 19 - Pre-1870's photograph of the Peyton Randolph House showing an eighteenth or early nineteenth-century porch, the original chimney stack to the house, and the building that served as the kitchen, laundry and servants quarter. Photographer unknown. Copy from CWF Library files.

Figure 20 - Photograph of the Peyton Randolph House, identified as dating to the 1870s. Note the replacement front porch and the kitchen to the west. Photographer unknown. Copy from the CWF Library files.

Figure 20 - Photograph of the Peyton Randolph House, identified as dating to the 1870s. Note the replacement front porch and the kitchen to the west. Photographer unknown. Copy from the CWF Library files.

Figure 21 - Pre-restoration photo of east wall elevation of the first floor east room, Peyton Randolph House. Photograph by Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond, Virginia circa

1930.

Figure 21 - Pre-restoration photo of east wall elevation of the first floor east room, Peyton Randolph House. Photograph by Metropolitan Engraving Company, Richmond, Virginia circa

1930.

Figure 22 - Photograph of the demolition of the passage partition in the second-floor southeast chamber, oldest section of the house. S. M. T., CWF, 1968.

Figure 22 - Photograph of the demolition of the passage partition in the second-floor southeast chamber, oldest section of the house. S. M. T., CWF, 1968.

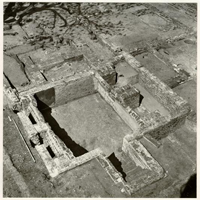

Figure 23 - Aerial view of the archaeological remains of Structure L from the southwest, showing the vaulted cellar and bulkhead cellar entrance. Andrew Edwards, CWF, 1984.

Figure 23 - Aerial view of the archaeological remains of Structure L from the southwest, showing the vaulted cellar and bulkhead cellar entrance. Andrew Edwards, CWF, 1984.

Figure 24 - Archaeological plan of Structure E. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 24 - Archaeological plan of Structure E. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 25 - Photograph of the remnants of Structures P, Q, and R from the north. Roy Jackson, CWF, 1984.

Figure 25 - Photograph of the remnants of Structures P, Q, and R from the north. Roy Jackson, CWF, 1984.

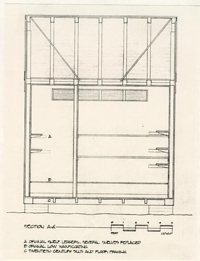

Figure 26 - Section through Elm Grove dairy, Southhampton County. Entrance to the small storage room on the left is through the larger room. Measured by Willie Graham, Mark Schara, Sallie Smith and Douglas Taylor. Drawn by Sallie Smith, CWF, 1982.

Figure 26 - Section through Elm Grove dairy, Southhampton County. Entrance to the small storage room on the left is through the larger room. Measured by Willie Graham, Mark Schara, Sallie Smith and Douglas Taylor. Drawn by Sallie Smith, CWF, 1982.

Figure 27 - Archaeological features thought to have existed during the ownership of Joseph Hornsby. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 27 - Archaeological features thought to have existed during the ownership of Joseph Hornsby. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 28 - Early twentieth-century photograph, subject identified as outbuildings at the Peyton Randolph site. If they are at this site, the building to the left is likely a late eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century dairy (Structure P). No foundations were discovered for the pyramidal roof building on the right. If the image has been accidentally reversed, this building may have been located in an unexcavated area. Photographer unknown, copy by Paul Buchanan, in CWF Library.

Figure 28 - Early twentieth-century photograph, subject identified as outbuildings at the Peyton Randolph site. If they are at this site, the building to the left is likely a late eighteenth- or early-nineteenth-century dairy (Structure P). No foundations were discovered for the pyramidal roof building on the right. If the image has been accidentally reversed, this building may have been located in an unexcavated area. Photographer unknown, copy by Paul Buchanan, in CWF Library.

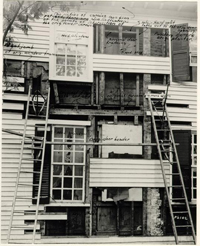

Figure 29 - Framing from north wall of house with notes by A. Lawrence Kocher. Openings to the porch tower were aligned vertically between windows. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1939.

Figure 29 - Framing from north wall of house with notes by A. Lawrence Kocher. Openings to the porch tower were aligned vertically between windows. Photographer unknown, CWF, 1939.

Figure 30 - Archaeological plan of the site as it appeared in the early-nineteenth century. Structures P and Q and the porch tower possibly were built late in the eighteenth century, but probably existed into the next century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 30 - Archaeological plan of the site as it appeared in the early-nineteenth century. Structures P and Q and the porch tower possibly were built late in the eighteenth century, but probably existed into the next century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 31 - Archaeological plan of the site, second half of the nineteenth century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 31 - Archaeological plan of the site, second half of the nineteenth century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 32 - Archaeological plan of the site, early twentieth century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 32 - Archaeological plan of the site, early twentieth century. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 33 - Archaeological plan of the site, circa

1920-1938. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

Figure 33 - Archaeological plan of the site, circa

1920-1938. Drawn by Natalie F. Larson, CWF, 1985.

BUILDING AN IMAGE:

AN ARCHITECTURAL REPORT ON THE

PEYTON RANDOLPH SITE

Willie Graham

Department of Architectural Research

Assisted by Andrew C. Edwards

Office of Archaeological Excavation

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

November, 1985

CONTENTS

| Acknowledgements | 1 |

| Introduction | 2 |

| Early Development of The Site | |

| First-Period Buildings on the Site | 8 |

| Main House | 11 |

| Structure A (Dwelling) | 27 |

| Structure D (Smokehouse) | 30 |

| Planting Beds One and Two | 32 |

| Structure J (Dwelling) | 34 |

| Structure M (Kitchen) | 37 |

| Well | 38 |

| Structure S (Dwelling) | 39 |

| Accumulation of Outbuildings | |

| Sir John and Lady Susannah's Tenure | 47 |

| Book Presses | 50 |

| Planting Beds Three and Four | 51 |

| Structure G (Dairy) | 52 |

| Structure H (Smokehouse) | 54 |

| Appendage to Structure H | 57 |

| Structure J Revisited and Structure K (Kitchen) | 59 |

| Structures F1 and F2 | 61 |

| Reordering the Site | |

| Peyton Randolph's Period | 62 |

| Expansion of the Main House | 67 |

| Structure L (Kitchen, Laundry, Servants Quarters and Forge) | 82 |

| Covered Way | 88 |

| Structure E (Granary) | 90 |

| Structure B | 94 |

| Structure R (Dairy) | 96 |

| Structure N | 101 |

| Betty Randolph | 103 |

| Maintaining the Site | |

| Joseph Hornsby's Period | 106 |

| Structure E (Granary) Repair | 108 |

| Structure C | 110 |

| Structure Q | 111 |

| Structure P (Dairy) | 112 |

| Porch Tower, Main House | 115 |

| Decline of the Site | |

| The Nineteenth Century | 119 |

| The Early Twentieth Century | 123 |

| Recommendations | 129 |

| Footnotes | 134 |

| Appendixes | |

| I: Paint Layers | 141 |

| II: Peyton Randolph Inventory | 144 |

| III: Humphrey Harwood Ledger Accounts with Betty Randolph | 149 |

| IV: Humphrey Harwood Ledger Accounts with Joseph Hornsby | 151 |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

In preparing this report, I am grateful for the assistance and advice I received from others. First and foremost, I would like to thank Andrew C. Edwards for briefing me on the history of the site and its examination by the Department of Archaeology and the office of Archaeological Excavation. All of the archaeological data used in the report came from his draft report on the site and from our discussions. Marley R. Brown, III, along with Andrew, provided helpful discussions about the interpretations of each feature and assisted in developing a framework for the analysis. I would like to especially thank Natalie F. Larson for providing the archaeological drawings from the recent excavation. Edward A. Chappell, in addition to editing several drafts of the report, helped in analyzing and interpreting the complexities of site development. Mark R. Wenger and Ronald L. Hurst shared their knowledge of house plans, inventories and libraries, and Orlando Ridout V, helped us unravel the mysteries of structures J, K and L. I am also indebted to Vanessa Patrick and George Yetter, who reviewed the final draft, and to Helen Tate, Gwen Miller, and my wife Karen, who typed the report.

INTRODUCTION

Excavations on lots 207 and 237, located on the corner of Nicholson and North England Streets in Williamsburg, were begun in 1939 by the Colonial Williamsburg Architectural Department. Analysis and restoration of the house and the reconstruction of two buildings began in 1939.1 Francis Duke directed the excavations and wrote the corresponding archaeological report, while James Knight did measured drawings of the excavated features and interpreted them.

The site was excavated three other times. in 1955, a somewhat more orderly approach was taken to the archaeology by the use of crosstrenching. Crosstrenching was carried throughout the rest of lot 207, but apparently lot 237, north of the reconstructed east wing, remains largely undisturbed to this day.

During the winter of 1977-78, the Department of Archaeology, under the direction of Ivor Noël Hume, reexcavated part of lot 207. This project was important in that, for the first time on this property, stratigraphic sequences were carefully analyzed.2

Most recently, careful excavation has beep continued by the Office of Excavation, under the direction of Marley R. Brown, III, and Andrew C. Edwards. Except for an area in the center section of the lot, the site was thoroughly 3 reexamined between its northern end and the kitchen (fig. 1). The unexcavated area is primarily that under the present driveway and the sites of two 1920s houses.

Because the site had previously been opened, stratigraphic relationships were difficult to establish. However, enough information was retrieved to help establish some relative dates, construction sequences, building functions, and structural techniques, and to either prove or dispel previous theories about the site.

Through a study of the new archaeological evidence and a reexamination of documentary sources, several construction patterns for the site have been identified. In its earliest phase, lot 207 probably consisted of the main house, structure J (a hall/chamber center-passage house), and structure A (a one-room house), all of which were adjacent to and faced North England Street. Structure M seems to have served as a kitchen for the main house and structure D served as an outbuilding to A. At about the same time, a lobby-entrance house designated as structure S was constructed on lot 237, facing Nicholson Street. Structures A, J and S appear to be rental property rather than support buildings for the main house.

The ownership of the two lots passed from William Robertson to John Holloway and then to John Randolph by 1724. 5 Some changes and additions were made during his ownership, but it was not until Randolph's son, Peyton took control of the site that major alterations were made. During the mid-eighteenth century, Peyton reoriented the main house, added a large addition to the east containing a new entertaining room, chamber and large central passage, and gave the building the appearance of a substantial, seven-bay Georgian house. The other dwellings on lot 207 were either torn down or were already gone by this time. A large walkway was installed down the center of the rear yard and new outbuildings were constructed flanking and facing the walkway, in contrast to the earlier orientation of buildings. The most substantial of these new outbuildings was a structure, possibly two stories high, that served as kitchen, laundry and servants quarters. A vaulted cellar was located under the southern portion, and the building was connected to the house by a hyphen. At the same time, a substantial amount of alterations were made to the interior of the house. These changes reflected not only a desire for up-to-date interior trim, but also an intention to introduce different room functions that were becoming fashionable in the mid-eighteenth century.

Throughout the rest of the century, the property was well maintained and all new construction related to the site order established by Peyton Randolph. The property was acquired by the Peachy family about 1800, and the house was 6 eventually turned into a boarding house. By mid-nineteenth century, most of the outbuildings in the rear had been demolished. The kitchen (structure L), smokehouse (structure H), dairy (structure P) and well survived into the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, as is evident in photographs of the site. By the 1920s, however, all eighteenth-century buildings had been demolished, except the main house.

EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE SITE

FIRST-PERIOD BUILDINGS ON THE SITE

In 1714, the Trustees of Williamsburg conveyed to William Robertson of York County a series of lots in Williamsburg. No contemporary plans survive that indicate lot numbers, but by reviewing a series of related deeds, tentative conclusions can be reached as to where these lots were located.3 Of the six lots conveyed to Robertson, this report concerns itself with the architectural development of what is thought to be adjacent lots 207 and 237. With its length running north and south, lot 207 appears to be that on the corner of North England and Nicholson Streets, the site of the main house and its mid-eighteenth century addition. Lot 207 probably extended northward to include structure A. Lot 237, then, would be immediately to the east.

The main house was constructed sometime between 1715 and 1723 and still in large part survives. At the same time the main house was constructed, or shortly thereafter, several other buildings were added to the site. As the site has been previously excavated, dating of features was fairly difficult. However, examining what stratigraphic and artifactual information remained, patterns of development on the rest of this lot, and partially on lot 237, became evident.

A series of buildings were constructed to the north of the main house during this period, most of which seem to 9 have been oriented towards North England Street. These features include structures A, D, J, M and S (commonly known in CWF reports as the "so-called east wing"), and probably the well (fig. 2). Structures A, J and S share some common features, and they may all have been dwellings. Structure M likely served as the kitchen for the main house, and structure D appears to have been some type of outbuilding for structure A, possibly a smokehouse.

MAIN HOUSE

The western portion of the main house has traditionally been dated to circa 1715. Typically, the deed transferring the eight lots to Robertson conditioned the sale, stating:

that if the said William Robertson his heirs or Assigns shall not within the space of Twenty four Months next Ensuing the date of these Presents begin to build & finish upon Each Lott of the said granted Premisses one good Dwelling house or houses of such dimensions and to be placed in such manner as by Once Act of Assembly . . . then it shall & may be lawful to & for the said Feoffers or Trustees . . . to have again as their former Estate to have hold & Enjoy in like manner as they might otherwise have done if these Presents had never been made.4

Whether or not Robertson complied with this stipulation in the required time is not known, but other evidence indicates that the house was built by the early 1720s at the latest.

In 1983-84, the American Institute of Dendrochronology was contracted to date the construction of the house using the key-year technique developed by H. J. Heikkenen.5 Tentative dates were established for the felling of trees used to fabricate some framing members and the oak gutters.6 Plates that carry part of the multiple-peaked roof and attic joists dated to 1715. Period-one rafters yielded a date of 1716 and the oak gutters came in at 1718. Problems related to analyzing tulip poplar samples, the lack of an adequate tulip 12 poplar area pattern, and short tree ring patterns combined to cast some doubt on the accuracy of these figures, but they seem to fall within the range of the traditional construction date for the house. The date derived from the oak gutter is reassuring in this regard.

On December 12, 1723, Robertson conveyed lots 236, 237, 207 and 208 "whereon the said William Robertson's Windmill stands together with the said Windmill and all Houses buildings Yards Orchards ways Waters profits Easements & Commodities . . . ." to John Holloway of the City of Williamsburg.7 Not long after this transaction, John Randolph acquired a lot, presumably number 207, from Holloway and moved his family into a house on the property.8 It can be deduced, then, that the construction of the house might have begun as early as 1715 or 1716, and it appears to have been up at least by the end of 1723. The house began as a relatively square, two-story frame building. Facing North England Street like most of the early buildings on the lot, it was constructed as a three-room-plan house with a corner passage. By arranging the three rooms and passage around a central chimney, the builder solved the problem of how to contain these spaces in a rather interesting manner.

In the early eighteenth century, the use of a passage as well as the expansion of the typical first-floor plan to include three rooms was in its early days of 13 development. This plan is similar to that of the mid-century Seven Springs in King William County and Mount Airy's southeast dependency in Richmond County (fig. 3). Following the conventional model of the period, one would expect the southeast room, with direct access to the passage, to be a hall.9 This room is not only the largest, but best finished room of the house. Diagonally across from it, also with direct access to the passage, was likely located the dining room. Finally, the rear corner room, without access to the passage but connected (most importantly) with the dining room, was the chamber. The use of a passage added a level of privacy that most earlier and many contemporary houses did not enjoy. By adding it, greater control was provided for circulation to the more formal rooms, and the chamber was further buffered from the public (fig. 4).

If the first-floor layout provided a reasonable solution to this type of plan, the second floor did not. The northwest and southeast chambers had direct access from the passage. Entrance to the northeast room, though, was gained through another chamber (fig. 5). The surprising feature of the second floor is the superior treatment of this northeast room. Not only was it the only second-floor room provided with above-chair rail panelling, it was unique in that oak, apparently unpainted, was selected for the task. How these rooms were used is unclear, as the more typical arrangement of second-floor rooms during this period amounted to a series 17 of plain and relatively undifferentiated spaces. The possible uses for this room range from simply a superior second-floor bedchamber to it serving as an anteroom associated with the room to the south.

Part of the early interior treatment of the house is known. The woodwork in the hall appears to be original and was certainly installed before the mid-century changes to the house. Room-height raised panelling with a boxed cornice encircles the room. As in all first-period rooms, the angled fireplace walls have been reconstructed. Cut through the bolection architraves of the windows (the only bolection molding to survive in the house) are square blocks with ovolos and flat panels. Above these panels the cornice breaks out, giving the effect of a keystone over each window (fig. 6). When the east window was removed in the mid-eighteenth century, the cornice over the window was not altered. At that time, a raised panel replaced the window, resulting in odd spacing for the panels on the wall. A new stile was added to the left of this panel, and it breaks through the top rail, indicating that the panelling, as well as the cornice, was installed before mid-century. Panels below the windows in the room, like those in the other rooms with early finishes, project from the wall. As one would expect of the hall, this is the most elaborately treated room in the house.

19The dining room originally was plastered. 10 Later, probably mid-eighteenth century, room-height panelling was installed over the plaster.11

The first-floor chamber contained room-height panelling with a box cornice. Having been heavily altered over the years, much of the panelling, chair rail, baseboard and door and window trim in this room is modern. The woodwork in the room appears to fit the pattern of the other early woodwork in the house, and there is no visible evidence that the panelling is later. It does seem unlikely, however, that the dining room, being a more public room, would have originally been plastered and that the chamber would have received full-height panelling. Further investigation should be pursued to determine the date of the chamber panelling.

A prerestoration photograph of the east wall elevation of the first-floor chamber (fig. 7) shows what appears to be an eighteenth-century doorway relocated for use as an entrance to the circa 1900 wing that was added to the rear. Since two interior doorways were removed from this room in the nineteenth century when wide openings were installed, this may represent one of them. Having a six-panel door with ovolos and flat panels on the room side surrounded by a three-part architrave, this differs from what was reconstructed for the two missing doors. Instead, bolection moldings similar to the early window surrounds in the hall were used.

21The first-floor stair passage contains no panelling and retains only part of its original trim. An original pair of follicated H and L hinges remain in place on the door below the stair. Most other early hardware throughout the house does not survive. Some fragmentary three-part door architraves still remain in this room. The top member, a cyma recta with a small bead, appears to be from the first period of the house. Used also in the second-floor northwest chamber, the same early architrave survived later alterations to the room. The date of these architraves is significant in dating the woodwork of some of the second-floor rooms. Like the other first-floor rooms, the passage contains a box cornice.

The second floor was greatly altered in the mid-eighteenth century. The passage received panelling below the chair rail, the southeast chamber had stiles and rails installed to carry wallpaper, and room-height panelling was placed over the earlier plaster walls in the northwest chamber. However, much early woodwork remains in the northeast chamber. It is the only room on the second floor to contain a box cornice, and its woodwork is of unpainted oak. Eventually, probably in the eighteenth century, the woodwork was painted, either to change its status to a less important room or simply to achieve a neater appearance.

The oak chamber has room-height raised panelling with a very flat profile for the panels. Two-part door 22 architraves were installed on the inside, with three-part architraves on the opposite side. The backbands on both sides are similar to those found in the first-floor stair passage, with the northeast room side being made of oak. It seems evident, then, that the panelling in this room was installed before mid-century.

Singleton P. Moorehead did paint analysis on the woodwork in each room.12 Except in the second-floor northeast (oak-panelled) room, all eighteenth-century woodwork, including later changes, exhibited red primer as its bottom coat. With the exception of the second sequence for the first-floor northeast room, the second coat (or first finish coat) was either gray or buff. This may prove a valuable tool for determining relative dates of woodwork installation. In addition, it suggests that the oak panelling in the second-floor room might not have originally been painted. The room's first coat of paint was buff or gray and may relate to the second finish coat of paints in other contemporary rooms.

The house being square in plan, the builder faced an unusual problem in designing a roof system. What he settled on was a multi-peaked roof structure which from the exterior appeared to be a version of a hipped roof topped with a flat deck. The chosen system was an alternative to a very large gable or pyramidal roof and may reflect both an economy of material and an aesthetic related to buildings of this depth.

23The Robert Carter house displays a similar system; the dependencies at Mount Airy reveal a different angle of the roof towards its peak forming a mansard-like roof, for the same reason. The James Geddy House, although not square, offers the same appearance when viewed from the south and west, its main facades.

At the two interior valleys of the roof, oak gutters lined with pine tar were installed to carry the water runoff (fig. 8). At both the east and west ends of this roof were interior walls covered with a mixture of unpainted riven clapboards and beaded and unbeaded weatherboards. Now protected by a later roof, the four interior planes still retain their early square-butt shingle roof (fig. 9). The combed ridge remains intact, providing a unique opportunity to study how a ridge was sealed from the weather. Where the shingle roof meets the walls, clapboards and weatherboards were cut out to fit tightly over the profile of the shingles. The walls were tarred, but there is no evidence for flashing between them and the roof covering.

Whether or not a square-butt shingle roof was used on visible surfaces is not known. The overwhelming majority of extant eighteenth-century shingle roofs on other surviving mid-century or later buildings have round-butt shingles.13 It appears that square-butt shingles may have become fashionable in the third quarter of the eighteenth century when a 26 cleaner aesthetic was in vogue. In the late nineteenth century, a square-butt shingle roof at the Randolph House was covered over with a standing-seam tin roof. our only evidence for the shape of visible shingles is from the hidden portion of the roof. It is possible that the visible roof utilized round-butt shingles and that, as an effort to economize on labor, square butts were used in hidden areas. However, if they were used on the outside, one might expect to find leftover round-butt shingles used on the interior, and no such evidence is present.

During initial excavation, the first-period stair foundation to the main (west) door was uncovered. In addition, a series of bulkheads corresponding to two separate cellar openings on the north, as well as the foundations for a later porch tower were found. The only one of these features that seems to have been contemporary with the construction of the house was the smallest central bulkhead foundation, sitting below foundations related to the covered way. Steps apparently led to a partially-excavated cellar, but no physical evidence of these steps survives.

STRUCTURE A (DWELLING)

In the northwest corner of the rear lot is a 16' x 20' foundation for a frame structure with an angled fireplace in its northeast corner. Earlier thought to have been Sir John Randolph's law office and later Lady Randolph's dower house, the building is now believed to have begun life as a dwelling. Artifacts from the occupation layer were primarily domestic debris, including a large amount of tea and tablewares apparently dating to the earliest period of the building's existence. In addition, very few craft or work-related items were found, suggesting that the structure initially served a domestic function and never had an extended life as a kitchen or craft building.

Brick piers with interstices filled by contemporary one-brick-thick walls supported a 4½" tall sill. Although the piers were bonded with shell mortar, the walls were partially dry laid. Rowlocks were laid below the piers to help span a seventeenth-century drainage ditch that ran diagonally across the site. A central row of piers likely supported a north-to-south summer beam. Several rows of nails were discovered that probably were used to secure floorboards in place. These nails indicated that floor joists were set approximately two feet on center and ran east to west.

28The corner fireplace was constructed of bricks that were different in appearance from those used in the foundations. Not enough brick remained to determine bond patterns. Brick infill between the chimney walls and the building walls were partially laid in mortar over the sills. Although the sill has long since rotted away, its impression remained in the masonry. The brick infill was not mortared to the chimney sides. on top of fill containing ash, mortar, plaster, brick and a fragment of manganese-decorated delft tile was laid a hearth, implying either that the hearth was rebuilt or that the fireplace was added. The delft tile is probably not connected to structure A, but a residual artifact already in the fill.

A layer containing numerous eighteenth-century artifacts, as well as plaster and additional delft tiles, earlier thought from previous excavations to have come from the remodeling of structure A, has been identified as fill, dispersed from a point on the North England Street side of the building. The material may have come from the-construction of the mid-eighteenth-century addition to the main house, which might have been carted down North England Street and discarded over the remains of the newly-demolished building.

Recent archaeological investigations determined that structure A was occupied sometime after 1720 based on the presence of white saltglazed stoneware and Yorktown 29 pottery. Its demolition layer had a TPQ of 1750, based on milled-edge clouded ware, refined agate ware and the absence of creamware, and it can be more tightly confined to the years between 1755 and 1765 due to the presence of milled-edge clouded ware.

Structure A probably did not serve as an outbuilding to the main house. Domestic artifacts recovered from the occupation layer suggest the presence of occupants with at least modest social standing, rather than slaves. Structure A bears an interesting resemblance to the planning of the other early structures on the site, several of which may have been houses that were rented. Structures A, J, M and S, as well as the main house itself, all reflect a relative lack of concern for symmetrical planning, possibly related to their early date. In all cases, chimneys were set into the corner of rooms. The main house had an off-centered front door, and when remodeled in the mid-century an attempt was made to not only change the orientation of the building, but to give it a symmetry that was not reflected on the interior. Unlike the later northern buildings on the two lots, these structures were oriented towards the street rather than the inside of the lots.

STRUCTURE D (SMOKEHOUSE?)

The earlier of two superimposed features located in the northeast corner of the yard, the foundations of structure D measure 12' 3" north to south by 11' 0". The walls are constructed with shell mortar and almost entirely of brickbats; what few whole bricks were found had mostly been used as stretchers.

The stratigraphy for both structures D and the upper feature, C, were disturbed when the site was plowed in the mid-nineteenth century, but enough information has remained intact to piece together a chronology. Below the destruction layer were three lenses. The top two were occupation layers with artifacts in the lowest lens dating to the early part of the century. No artifacts were recovered from the upper level. The bottom of these layers forms part of another which extends to the outside of the foundations. Artifacts in the layer on the outside were deposited between circa 1720 and circa 1800. Since D was constructed after the layer began collecting but before it was complete, the date of construction is sometime in between. The destruction layer contained creamware and therefore had a TPQ of 1762. The major occupation layer for structure C contained artifacts ranging in date from circa 1775 to the mid-nineteenth century. It can be concluded, then, that structure D was built sometime after 1720 and 31 destroyed before 1775.

Structure D probably served as an outbuilding for structure A. Unfortunately, the type of outbuilding function is not known. However, the existence of charcoal in the top occupation layer and the size of the building may suggest use as a smokehouse. The poor quality of materials (mostly bats) and construction techniques (use of the limited whole bricks almost entirely for stretchers and not for bonding the wall thickness) evident in the foundations imply a building that was less well constructed than structure A, as one would expect.

PLANTING BEDS ONE AND TWO

A total of four planting beds were uncovered in the rear of the lot. Located slightly to the southwest of structure D are the earliest planting beds, one and two. The beds, separated by about one foot of subsoil, measured twenty feet east to west. Planting bed one was eight feet wide, while the southern bed measured four feet.

The bottom of these beds was lined with numerous fragments of glass bottles, combined with ceramics, bone and oyster shell (fig. 10). Presumably these materials were applied to the bottom of the beds in an attempt to provide better drainage. In planting bed one there are indications that the fragments were placed against a board.

The artifacts associated with the features suggest the beds were laid out circa 1715-1720. Closeness to structure A and distance from the main house suggest that they were associated with the former. The beds, whether for flowers or vegetables, are interesting in that they may represent an attempt at experimentation. No comparable features have been found on other Virginia sites. The beds, along with beds three and four, were abandoned by circa 1740.

STRUCTURE J (DWELLING)

Identified by the letters J, K and L, this complex of foundations reveals several different stages of development, some of which must indicate drastic alterations to the frame and at least one of which seems to represent a complete change of structure (fig. 11 ). The first phase, structure J, was a center-passage, single-pile building. Measuring 31' 9" north to south by 12' 2½" with a 7' 0" shed, it contained an interior chimney, with a cooking-size fireplace and a rear (east) shod of undetermined length, both of which could either be original to this structure or added soon after initial construction (see fig. 2 ). The brickwork of the chimney is not bonded in, but is very similar to that of the foundations. Although the foundations are not complete, several features indicate that these were the original perimeter walls for the main block., Rowlocks used on the bottom course of the foundation tie most of the east walls together, along with the north partition wall. Halfway along its length, the east wall displays a more regular bond and is integral with the other partition wall. This partition is tied to a piece of the west wall, while the west wall is bonded to the southernmost wall. In general, all the foundation bricks of this period are light-colored and soft, contrasting with those of the later period, which are darker and harder.

36The interior dimensions of the north room containing the interior fireplace measured only 10' 9" square. A 7' 9" passage divided the north room from the unheated 10' 9" square room to the south. orientation of the building was towards North England Street as evidenced by the location of the early shed to the east. The function of the building was probably similar to that of structure A and the eastern-most section of the main house. All were probably residences, and the two northern buildings may have been rented. Both structures J and S contained cooking fireplaces, and structure M served as a kitchen for the main house. There is no evidence for kitchen services to structure A.

Little remains to date structure J. An ash layer over the hearth contained creamware (TPQ 1762), as well as a shoe buckle commemorating Admiral Vernon's victory over the Spanish in 1739. The deposit, however, is more likely associated with the later exterior chimney.

STRUCTURE M (KITCHEN)

Not much remains of structure M. The frame building was located to the south of structure L and its foundations were probably cut through by those of L. The remains consist of a north-facing 8'11 ¾" x 4' 9" corner fireplace and the remnants of two sections of wall foundations. The jagged remains of foundations imply a one-brick thick wall. Laid in a somewhat random English bond and shell mortar, the well-fired brickwork of the chimney contrasts with the disorderly laying of wall foundations. These bricks were predominately rowlocks and were in poor condition.

Separated from its stratigraphy during the 1938 excavation and offering few informative artifacts, structure M is difficult to date. It was down by the time structure L was constructed and was considered by Francis Duke, who dug the site in 1938,14 to date to the first or second period of the large kitchen complex. The size of its fireplace and close relationship to the house suggests it might have served as a kitchen. Destroyed by circa 1760 or before, it is likely to have been part of the earliest development of the site. Its off-centered fireplace appears to be related to the same type of planning that created structures A, J, S and even the first period of the house itself.

WELL

Located just north of the kitchen and to the west of structures G and H is an eighteenth-century well. This is the only well on the lot and probably served the site from the early eighteenth century. A windmill was constructed above the well in the late nineteenth century. Use of the well continued until the 1920s and by 1924, the date of construction for the Skillman House, it was completely filled in. Because wells are repeatedly cleaned and the use of this well extended into the 1920s, it is unlikely that excavation would yield many early artifacts. The dangers involved and the prospect of not recovering much useful information led to a decision not to excavate the well.

The well shaft measures about four feet in diameter and is roughly circular. Interestingly, it is constructed of conventional rectangular bricks instead of the more specialized, wedge-shaped well bricks. A square pad, constructed of brickbats, was added later. Possibly this is part of Humphrey Harwood's repair work on the well on August 19, 1784.15 There is no remaining evidence for a well head.

STRUCTURE S (DWELLING)

Connected to the eastern end of the mid-eighteenth-century addition to the main house, structure S was constructed on what is thought to be lot 237 (fig. 12) . Excavated in 1938 and reconstructed shortly thereafter, structure S appears to have been a dwelling separate from the main house and connected to it in the mid-eighteenth century. After construction of the middle unit, the two buildings shared a common wall, but there was no circulation between them.

Measuring approximately 34' 6" east to west by 20' 6", structure S appears to have been a lobby-entrance house. The chimney base sits slightly off center against the rear, north foundation wall, allowing for a hall, that is, the larger room to the west, and a chamber to the east. Both rooms were heated with a fireplace that was slightly angled into the rooms. Entrance to the two rooms was made more private than the conventional hall/chamber plan by the addition of a lobby16 that served as a small passage. Introduced to Virginia early in the eighteenth century, the passage was a relatively new component when the early buildings on lots 207 and 237 were being constructed. Structure S, in an effort to economize by building only one chimney, used the lobby-entrance plan in order to facilitate a circulation space. Structure J, requiring only one chimney, employed a center passage, which 41 became the most common eighteenth-century form. The main house, composed of three rooms and a corner passage, also economized and used one chimney to serve all fireplaces in the house.

The cellar must have been divided into two rooms, with possibly a third, smaller room between them. A similar arrangement can be found in the cellar at the Ridout House, Annapolis. On one side of the main cellar passage are two rooms, a kitchen and laundry. Between these two rooms is a much smaller room that serves as a passage between the two and contains shelving for storage. Entrance to the cellar of structure S is through a bulkhead to the south on the east facade. The bulkhead contained five steps with wood nosings. According to the archaeological drawings, the main foundation walls were built of common-bond brickwork using oyster shell mortar. The walls displayed evidence of grey paint. Two relieving arches were built into the east wall, apparently to span a section of earth suspected to be weak. In spite of this effort, part of the wall did sag. on the north wall behind the chimney the foundations break, apparently in an effort to save brick. The chimney was laid in English bond, and the floor was covered with brickbat paving.

At the time of the reconstruction of the house, all archaeological features associated with it are likely to have been destroyed. In addition, the construction of the parkway tunnel disturbed a large amount of this area. The information 42 which can be derived from this feature has to be analyzed from the photographs, drawings and an earlier archaeological report.

The first question is when was this structure constructed. The archaeological site drawing by James Knight indicates that the foundations are first period, colonial brickwork. A photograph (fig. 13) of the east end of the main house, looking at the archaeological remains of structure S, reveals much about the construction sequence of the two parts and provides an idea of what the destroyed building looked like. When the mid-century block was added to the main house, the framing for the gable end of structure S was removed and replaced with brick. Both the first-floor and the attic levels are demarcated by step-backs in the brickwork. Oddly, the new attic wall was coated with rough plaster, but not the first floor. Possibly the first-floor brick wall was firred out and plastered, or contained closets, hiding the brick wall beyond. Another photograph (fig. 14) taken during the excavation shows the northeast corners of the main house at the juncture of structure S. Here the brick end of the main house clearly sits on top of the foundations for S, establishing S as the earliest feature of the two.

The roof outline for structure S is delineated in plaster on the east facade of the mid-century addition to the house and describes roughly a 49 degree roof. What exterior brickwork was visible above the roof line of structure S was 45 laid in Flemish bond. The bonding changes to English below, where it would have been hidden from view.

After the demolition of structure S, two windows were cut into the east brick gable. It is possible that the first-floor level of brick wall was veneer added after demolition of the wing, which thus explains the absence of plaster at this level. The building is known to have stood at least until circa 1782, as it is shown on the Frenchman's Map.

Structure S was reconstructed in 1939-40 with modern interiors for use as a residence. For this reason, the present plan of the house does not reflect the original. An interesting feature of the reconstruction is the use of round-butt shingles for this portion of the house. The architectural report, describing the reconstruction, indicated that "recent research by the Architectural Department reveals the common type of hand split shingles have been cypress with round butts."17 The report also mentions the recent installation of round-butt shingles at the Wythe House, but even so, this must have been one of the earliest twentieth-century uses of round-butt shingles in the Historic Area.

ACCUMULATION OF OUTBUILDINGS

47SIR JOHN AND LADY SUSANNAH'S TENURE

John Randolph, educated at the College of William and Mary and the Inns of Court, was a member of the House of Burgesses. Serving as clerk to the House, Randolph was sent to England several times as its representative. On one of these occasions, he was knighted.

At his death in 1737, Sir John Randolph left his wife, Lady Susannah Randolph, with life rights to the property. Between the purchase of the lots in 1724 and the mid-eighteenth century when their son Peyton began to make major changes to the site, this generation of Randolphs added several outbuildings to the rear yard, but did little to change its general character. At least structures E, 11 and K were built during this period. Structure H, surviving into the twentieth century was oriented towards the house. This may have been the first step in reorienting the rear yard. Structure H served as a smokehouse, K as a kitchen, and G possibly as a dairy. Presumably structures J and M were destroyed by this time. In addition, two more planting beds were laid out in the vicinity of structure A (fig. 15).

BOOK PRESSES

In his will, Sir John Randolph left his son, Peyton, his "whole collection of books with the cases in which they are kept."18 These book cases must have taken up a substantial amount of space, and the possibility that a room was given over as a library cannot be ruled out. However, it has been suggested that it is very unusual to see the use of book presses this early in the century and even more rare to find rooms set aside as libraries.19 often books were stored in closets or trunks and were found in many rooms, including passages. William Byrd did have a library at Westover, but this seems quite unusual for the times. It appears most likely, then, that although the presses indicate an unusual level of sophistication in furnishing, they were probably distributed throughout the house.

PLANTING BEDS THREE AND FOUR

About twenty feet to the west of planting beds one and two were discovered two later beds, three and four, both oriented north and south. Planting bed three was thirty-two feet in length and twelve feet wide and was badly disturbed in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century. Bed four measured twenty-nine feet long, eight feet wide and about six inches deep. A series of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century postholes cut through much of bed four and structures B and E were constructed partially on top of it.

The two beds were laid out circa 1724 and were abandoned at the same time as the earlier beds, about 1740. The major paving material in the beds was bone, although it also contained glass, oyster shell and ceramics. Planting bed four used oyster shells as its predominate paving material, along with the rest of the materials found in the other beds. The use of paving materials for the bottom of the beds suggests horticulture experimentation, as does the selection of different principal paving materials for three of the four beds. Again, the closeness and similarity in date to structure A and the distance from the main house indicates that the beds were probably associated with the smaller dwelling.

STRUCTURE G (DAIRY?)

Aligned with the eastern edge of the earliest portion of the house and located to the north of the kitchen complex are two relatively small foundations, structures G and H. Structure G measures ten feet north to south and likely the same east to west. Regrettably, it too was separated from the adjoining stratigraphy during earlier excavations. As a result, dating the construction and destruction of the building has been difficult. Because the building roughly aligns with the eastern edge of the earliest portion of the house as well as buildings K and H, it may predate the mid-eighteenth century expansion of the house.

The marl yard spread (walkway 2, Block 28B), with a TPQ of 1779, appeared before structure G was demolished, providing the only solid evidence for its dating. Marl walkway no. 1., with a TPQ of 1820+, does cover the foundations, demonstrating it existed by this period.

English bond with shell mortar was attempted on the west facade in the north corner, but quickly gave way to a more casual bond, incorporating reused brickbats and rowlocks, as well as whole bricks. The foundations were partially repaired while other damaged areas were not patched. Whole bricks and bat bricks were aligned perpendicular to the walls as paving for the floor. There is little evidence remaining 53 to assist in determining building function. It may have originally been a dairy paired with a smokehouse and located next to the kitchen. If this was the case, the structure was eventually either supplemented or replaced by one or more later dairies to the northeast with structures P, Q and R.

STRUCTURE H (SMOKEHOUSE)

Structure H is located directly to the south of G and is also roughly aligned with the eastern edge of the first construction period of the house. Measuring 12' 4 ¾" north to south by approximately 12' east to west, this building was constructed with well-fired brick, and laid in English bond and shell mortar. The foundations are in very good condition.

Inside the building are two features which were likely hole-set posts. One is directly at the center of the building; the other is located in the northwest corner. The latter Ray have supported a bench, and the center post might have carried the apex of a pyramidal roof.

An interior refuse layer with a TPQ of 1820 (contains both whiteware and a dated 1769 Thomas Hornsby bottle seal) was located beneath the 1960s demolition layer from the Skillman House. Below this was a layer of clay, thought to be a floor surface. The clay layer was intruded into by the two post holes, and has a TPQ of 1779. Below this layer was another layer consisting of loam and sand with a TPQ of 1720. 20 The layer was relatively thin on the inside, thicker on the outside, and intruded into by the foundations. In the builder's trench to the west, thin layers with TPQ's ranging from 1700 to 1765 were discovered. A very small piece of pearlware was 55 discovered in one of these layers, but possibly it should be disregarded. In summary, the building was constructed sometime after 1720, a clay floor installed after 1779, and then the clay floor was sealed by a refuse layer after 1820.

In the layer with a TPQ of 1820, coal and a large amount of burnt material was found. This, along with a circa 1907-08 photograph of the site taken from the southwest, support the premise that structure H was a smokehouse (fig. 16). The photograph shows a square, pyramidal-roof frame building that faces to the south. Its central door opens out and is hinged to the east. Although unclear, the rafters apparently sit directly on the plates with no overhang and a crown molding carries the bottom row of shingles. The location of the door to the south suggests that the building was constructed before the central walkway was installed and the orientation of most buildings changed from facing North England Street to facing inward on the yard. This photograph will be discussed more fully under structure P.

APPENDAGE TO STRUCTURE H

A line of bricks set on edge, along with a vertically-set stone, connects to the southwest corner of structure H, runs parallel to its west facade, and makes a ninety-degree turn before meeting the southeast corner of the well (fig. 17). The feature was covered by a circa 1820 refuse layer. On the inside of the feature to the east are a series of lenses, with TPQ's of 1700 to 1765, which cover the builder's trench of structure H.

The function of the feature is unknown. Possibly it defined a narrow walkway to the east and north. However, it seems more likely that it defined the marl yard spread that runs along the eastern side of the kitchen and south to structure G. Although most of the spread is not well defined, from the northeast corner of the kitchen complex there extends an edging for the walkway that is quite similar to this feature. If both of these rows of brick define the yard spread, an odd configuration would result and the walk would be narrowed to about two feet at the smallest point.

STRUCTURE J REVISITED AND STRUCTURE K (KITCHEN)

Sometime before mid-century, the complex of foundations constructed as structure J (the center passage building with a rear shed), was heavily remodeled, once and perhaps twice. one possibility is that the earliest shed was replaced with another slightly deeper and extending the full length of the building. The relevant wall is constructed of darker bricks laid in a more regular pattern than the first-phase brickwork. In addition, like those of the first shed, these foundations were abandoned and at least partially covered by later foundations. It was also perhaps in the second phase that the old interior chimney was replaced with an exterior one, thus freeing up additional space in what must have been a very cramped room. There is a narrow opening in the masonry to the west of the new fireplace, possibly for an oven. However, to the east of the chimney there also survives a single-course pad of brick that appears to be contemporary with the second-period changes. This seems to be the base of an oven with access from the outside, despite the fact that we know of no surviving ovens that have floor-level hearths.

Conceivably constructed at the same time as the second-period shed, but possibly later, was a large room (Exterior dimensions of 16' 7½" north to south by 14' 6"). with a large interior cooking fireplace to the east (see 60 fig. 4). The addition, labeled structure K, was constructed of bricks that are similar in appearance to those of the second shed, but the two sections are not bonded together and in general more brickbats were used in the east room than in the shed. At this time, at least part of the building's function was changed to that of a kitchen. Whether this change involved downgrading a dwelling or adding a cooking room to a work building is unknown.

A more likely solution is that structure J was razed and completely rebuilt as a new building, except for a portion of its foundation, which was reused. Instead of the new west wall being the foundations for a very slightly deeper shed, it served to support a new structure that spanned from here to the old east wall of J. Structure K was incorporated into the plan running perpendicular to the east wall of the new building and flush with its south wall. This would allow for a much more believable intersection of the two parts. In the previous scenario, the roof of structure K would have extended over the new shed before meeting the main roof of structure J. The complete rebuilding of the feature would also be contemporary with the construction of exterior chimney and two ovens on the north wall.

STRUCTURES F1 and F2

Not much is known about structures F1 and F2, which were excavated previously and not reexcavated during the most recent project. They are likely to represent two separate buildings. F1, the older foundation of the two, is located slightly to the south of F2. On his archaeological map of the site, James Knight, labels Fl as first-period colonial brickwork and F2 as modern. F1 was constructed of English bond brickwork and oyster shell mortar. The brickwork from structure E that was labeled "modern" by Knight turned out to be mid-nineteenth century and could also be the case for structure F2.

When the driveway is relocated, these features should be reexamined in order to better determine their size. date and function.

REORDERING THE SITE

63PEYTON RANDOLPH'S PERIOD

In his will, Sir John left his wife life rights to this property, the ownership passing to their son Peyton at her death. Although Lady Randolph is known to have lived at least until 1755, Peyton seems to have taken control of the property before that date. As early as 1751, the house is referred to as "Mr. Attorney's." 21. About the same time, the house and site underwent major alterations. In general, this involved the construction of a two-story addition to the house that included a spacious center passage, a large entertaining room, and a second-floor chamber with numerous closets. The kitchen was torn down and replaced with a larger one. The new kitchen contained laundry facilities, servants' quarters, a vaulted cellar under the southern end, and a covered way connecting it to the main house. The rear yard was reoriented from North England Street inwards toward a raised marl path that ran from the new passage doorway of the main house to the back of the lot. New outbuildings were constructed while old ones were torn down. In addition, the main house also changed orientation to face Nicholson Street (fig. 18).

The changes to the site brought about by Peyton reflect a desire to either elevate his image, or at least to create a backdrop worthy of his ambitions. Like his father and younger brother John, he studied law at the Inns of Court. 65 Being named Attorney General for the Colony in 1748, he was known as "Mr. Attorney" until 1766 when he became speaker of the House of Burgesses and was from then on referred to as "Mr. Speaker." 22 In 1748, Peyton was elected to the House of Burgesses, a body which according to John Reardon, had become the focus of power in Virginia. 23 Working his way up the sociopolitical ladder, Peyton Randolph was named Speaker of the House and-later president of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia. During the course of the second Continental Congress, on October 22, 1775, Peyton Randolph died. A year later his body was returned to Williamsburg to be buried in a family vault in the chapel of the College of William and Mary.

New construction during Peyton Randolph's residence included replacement of earlier buildings probably thought of as inadequate, as well as the addition of new functions. As mentioned earlier, the kitchen was rebuilt. What seems likely to have been a large, two-room dairy (structure R) was constructed. This seems to have largely negated the need for structure G. A granary was built, as was a storage building and probably another large structure of unknown function (structure F).

Because of Peyton Randolph's social position and pretensions, his new outbuildings must have been among the best constructed in Williamsburg during this period. It is 66 interesting to note that the foundations had a strong orientation toward the yard, reflected by the use of better brickwork on these faces, and fairly crude work on the back sides. In the case of the new kitchen, old foundations were reused except for the sides facing the main house and interior of the yard. The yard face of structure E, likely to have been a granary, was well laid in English bond. The back side, facing North England Street, probably either had hole-set posts, or at most, sat on wood stump piers.

Features demolished during this phase include structures A, D and K. The four planting beds, structure J and structure M were all gone before mid-century.

EXPANSION OF THE MAIN HOUSE

By mid-century, large entertaining spaces were becoming fashionable for urban gentry houses. Public places, such as Raleigh and Wetherburn's taverns and the Governor's Palace, had by the early 1750s acquired new, large rooms for entertainment.24 Whether he was emulating the model of these more public places, or influenced by a broader pattern, Peyton Randolph began construction on his two-story addition in 1753. 25 The addition included a large, first-floor entertaining room, a large, second-floor chamber, and a fairly grand central passage that separated these rooms from the older portion of the house.

The new addition physically connected the house to the one-story structure S on the east, but did not allow for interior circulation between the two. The house was given a new orientation to the south, and although far from symmetrical on the interior, was designed to look like a seven-bay Georgian house on the exterior. In contrast, the back (north) elevation honestly reveals the building's growth.

Previous archaeology uncovered a 7' 0" deep by 9' 8" wide brick foundation for a stoop or porch for the new front door. Although there was little or no evidence for three-sided stone steps leading to a large stone platform, that is what 68 was reconstructed. A pre-1870s photograph of the house shows what could be a colonial porch on the front of this facade (fig. 19). Two unfluted, Doric columns support a three-part architrave and pediment. Pilasters are used against the wall. Another photograph, thought to have been taken during the 1870s, shows a different porch in a dilapidated condition (fig. 20). This porch probably reused the same foundations and pilasters, but incorporated square porch posts supporting a flat deck and balustrade. At this time the (period-two) second-floor passage window was enlarged as a doorway to the porch deck. A reference to the earlier porch was made in a circa 1875 letter by Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman, stating:

That historic Colonial porch has in these later days given place to a tawdry gimcrack affair which is an offense to the eye and to good taste.26

The wood belt course on the earlier building was continued across the new facade. The old eastern corner board on the south facade was retained as well as the hipped roof to the west. It was apparently at this time that the roof height was extended to form a peak.27 Dendrochronology dated one of the upper rafters to the same period as the mid-century changes, but the lack of an adequate number of samples should again make us cautious as to the accuracy of the results.

The new first-floor east room appears to be the principle entertaining room of the house. Not only is it the 71 largest room, but it was the most elaborate. A large and expensive marble mantel is flanked by two closets or buffets (fig. 21). Doors, sash and their jambs are of walnut. These doors, like most of the doors installed in this period, contain eight panels with four large, vertical, central panels flanked by top and bottom horizontal panels. These somewhat unusual doors were also used at Mount Vernon, Fairfax County; Scotchtown in Hanover County; and the Upton-Scott House in Annapolis. Hardware for the buffet doors, the room door, the door across the passage, and the doors in the new second-floor chamber were all expensive brass mortise hinges with turned finials. The room contained floor-to-ceiling raised panelling and a box cornice.

The second-floor chamber in the new east addition was also well finished. It contains room-height panelling that used ovolos and flat panels. Although at times this type of panelling was perceived as a superior room treatment.28 to Peyton Randolph it was not. A crown molding instead of a box cornice caps the room. Flanking the fireplace are two closets, utilizing the eight-panel doors found in the room below it. Unfortunately the backband for the fireplace has been replaced. The main door, sash and door and window surrounds are of walnut.

Evidence points towards Peyton Randolph having had this room constructed with a north to south partition between 73 the western two windows. This space presumably contained two closets. The northern closet lighted by a window probably was entered through the east chamber. The southern closet was lighted by a window and probably could have been entered either from the room, or more likely through the vestibule that the partition created.29 Mortises in the floor and lap joints in the attic joist for studs, paint ghosts on the floor, cornice repair, and extra wide stiles on the north and south walls all indicate that a partition had formerly been in this location. In addition, the inventory of Peyton Randolph's estate taken at his death lists, in what seems to be a bedchamber, "4 pr Window Curtains 40/."30 As Ron Hurst points out, if this room were partitioned, it would be the only room of the house with four windows. The framing behind the existing west wall should be examined to determine if this paneled wall had been relocated when the partition was removed.

The central stair passage was constructed to provide a fairly grand entrance to the house, as well as a barrier to the two new rooms. A heavily restored arched window lights a stair that has since been removed and later reconstructed. Walnut doors lead to the new room to the east and to the southeast room of the old house. Chair-rail-height raised-panel wainscoting was installed in the passage, and in the stairwell vertical stiles breaking up large panes of plaster were used. The door and casing below the stair appear to be 74 original, incorporating a pair of foliated H and L hinges from the period-one house. Interestingly, ceiling-height raised panelling was installed at the top of the stairs in the passage. This seems odd, as it would appear that the second floor was treated in a superior manner to the first-floor passage, unless the plaster walls were wallpapered. During the restoration, the door in the second floor passage was returned to a window.

At the same time as the addition was built, the old portion of the house received new interior trim. The first-floor northwest room acquired room-height raised panelling over the earlier plaster walls. The same treatment was possibly applied to the northeast room at this time. On the second floor, the northwest chamber received room-height panelling similar to that used in the new east chamber. Interestingly, this was also used below the chair rail in the old second-floor stair passage but was not added to the passage below it.

The southeast room was also altered at this time. Stiles and rails similar to those used in the new stair landing were added after the window on the east wall was removed. A wide beaded chair rail sat on a panel rail, as did the baseboard and cornice. The door cut into the room by Peyton Randolph had an extremely wide stile between it and the corner, another indication that this trim related to his period. 75 Shallow rabbets were cut out of the stiles and rails and were lined with tack holes.31 Wallpaper was likely tacked to the stiles and rails, and through the use of rabbets, the paper was set flush with them.

Circulation through the second-floor chambers was still awkward, even with the addition of the new passage. Neither the old passage (having been relegated to a back stairway) or the new passage gave direct access to the second-floor northeast chamber (oak-panelled room). After the other mid-century changes to the house, but presumably during Peyton Randolph's lifetime, a narrow passage was installed in the second-floor southeast chamber. The passage allowed for independent access to the oak-panelled room and the southeast chamber. Stiles and rails existed on the east wall of the passage but not the new west wall. Cut through the door jamb to the oak-panelled room, the partition did contain stiles and rails on the room side, possibly indicating that the wallpaper was reset after the southeast room was diminished in size. Colonial Williamsburg removed this partition in 1968 (fig. 22). Demolition photographs show that the studs were hewn and pit sawn. Whatever its practical advantages, the recent alteration is regrettable from the standpoint of interpretation as well as conservation, as the partition was an important illustration of increasing concern for privacy in the Randolph household.

77Room usage became more complicated during Peyton's period. Four types of information give us the most clues as to how the house was used. Room size, room finish, circulation patterns and the inventory for Peyton Randolph's estate begin to suggest how the house functioned.

The new first-floor east room, due to its larger size, superior finish, and location across the passage from the earlier room, probably served as the main entertainment space for the house. The first lines of the inventory list a number of items which indicate a room that was at least partially used for dining. According to Ron Hurst, these items fit best in this large room. If it is assumed that, in general, the inventory groups items from each room together, these pieces would literally cram the smaller rooms of the old house. Conversely, the items listed for other rooms are not enough to fill the new east room. Probably the most telling evidence is the "492 oz. Plate @ 7/6." With no piece of furniture listed to contain these items, they could be nicely stored in the buffets flanking the fireplace. Although shelving has been removed from the closets, clear evidence for them survives. The two mahogany tables and one sideboard, among other things listed in the inventory, give evidence of the room being used at least in part for dining. The typical house plan through at least the third quarter of the eighteenth century was one in which the hall or parlor was 78 the principal room and the dining room was secondary to it. Some alternatives to this formula are known to have existed. For instance, an eighteenth-century plan of Menokin, Richmond County, labels functions for each room. A study, two chambers and a dining room make up the first-floor plan. The dining room is the largest room of the house. Presumably this room served the function of both the dining room and parlor since no space was designated for parlor usage. At the Miles Brewton house in Charleston, dining was one of the functions of the main entertaining room.32 It is therefore possible that the new large room at the Peyton Randolph house served both as the principal dining room and as the location for other entertaining functions, even though another room seems to have been a parlor.

The most likely candidate for the parlor is the old southeast room. As the largest of the remaining first-floor rooms, it is located immediately across from the new entertaining room and is directly accessible through a major door from the new passage. The inventory includes a list of items that is typical of parlors, such as a dozen mahogany chairs, a card table, two tea tables and one looking glass.

Peyton also seems to have established a space primarily for use as a library, possibly in the northwest corner of the first floor. The inventory lists "6 mahogany Book Presses at 30/ . . . Do Writing Table £3 1 large Mahogany table 5 . . . 1 Round table 15/ 1 Paper Press 79 10/ . . . 1 Chaffing dish 5/ 1 dry rubbing Brush 3/ . . . 1 Clock £5 1 pr Back Gammon tables 10/." The next few items appear to be in the adjoining passage. They include "1 old pine table 3/. 6 Mahogany Chairs 40/" and "1 lantern." By establishing a room as a library, Randolph reduced the old house plan to a hall/chamber house with the third room being his library. It may also be for this reason, in part, that he saw a need to build the new addition.