James Geddy House Architectural Report, Block 19 Building 11 Lot 161 Originally entitled: "The James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop Block 19, Building 11, Colonial Lot 161 (61)"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Research Report Series-1450

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

The Summary Architectural Report is a résumé of information on the subject building, condensed from data filed in the Architects' Office. It is intended for the use of authorized personnel within Colonial Williamsburg, and visitors having a serious interest in colonial American architecture. It is not for public distribution.

THE JAMES GEDDY HOUSE AND SILVERSMITH

SHOP

BLOCK 19, BUILDING 11

COLONIAL LOT 161 (61)

SUMMARY ARCHITECTURAL REPORTPRELIMINARY

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

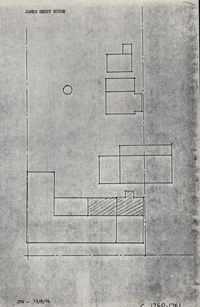

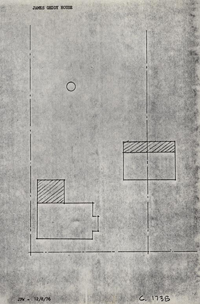

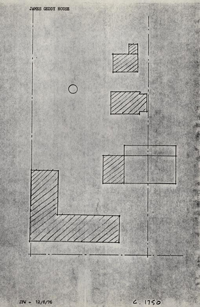

JFW-12/8/76 C. 1738

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

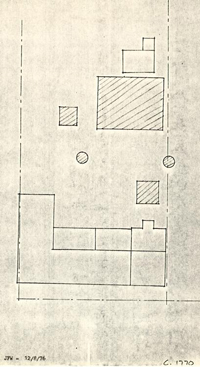

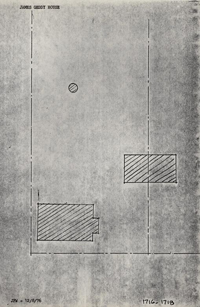

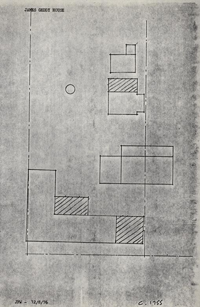

JFW-12/8/76 1716-1718

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JFW-12/8/76 c. 1750

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JFW-12/8/76 c. 1755

THE JAMES GEDDY HOUSE AND SILVERSMITH SHOP

SUMMARY ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

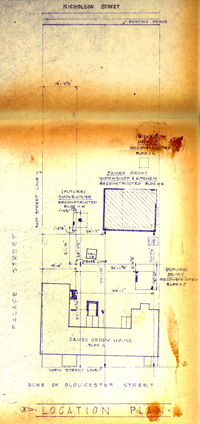

LOCATION:

The James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop is located

on Colonial Lot 161 (61)1 at the northeast on

corner of Palace Green and Duke of Gloucester Street. The lot, which measures

4/10 of an acre, is contiguous to Nicholson Street on the north and is bound on

the east by the adjoining Norton-Cole lot [Colonial Lot 162 (62)].

HISTORY:

Lot 161 was created in the town plan of 1699, but was

not sold by the trustees of Williamsburg until 1716. Samuel Cobbs, the first

owner, purchased lots 161 and 162 together. Apparently Cobbs fulfilled the

statutory building requirements, for the land did not revert to the city and the

consideration increased from thirty shillings to forty pounds by the next

conveyance. In 1719 Cobbs deeded both lots to Samuel Boush, Jr. James Geddy, a

gunsmith, bought lot 162 from him in 1738, having previously acquired lot 161.

The date and nature of Geddy's first transaction are enigmatic obscure,

but the deed of 1738 describes lot 62 (162) as "adjoining the Lot whereon

the said James Geddy now dwells".2 That Geddy

legally possessed both lots is proved by subsequent deeds. The two lots were

held by the Geddy family until 1750, when Anne Geddy, widow of the gunsmith,

sold lot 162 to James Taylor, a tailor. James Geddy, Jr., a silversmith, bought

lot 161 from his mother in 1760 and continued to live there for the next eleven

years. In 1777 he moved to Dinwiddie County, renting his Williamsburg property

until he sold the lot to Robert Jackson in 1778.3

The Geddy family occupied lot 161 for at least forty

years during the eighteenth century. This The Geddy ownership was the

longest ownership in the history of the lot. Archaeological and

documentary research confirm that James Geddy and three (3) of his sons operated

their trades in the same place they resided. David and William

Page 2

Geddy worked in their father's gunsmithing craft and

apparently engaged in brass founding. James Geddy, Jr. was a silversmith who

dealt in all the branches of his trade. Though the Geddys owned lot 162 (62) for

twelve years, their domestic and craft activities were concentrated on lot 161.4

The only eighteenth-century building on lot 161 dates from the Geddy Tenure.

GENERAL APPEARANCE:

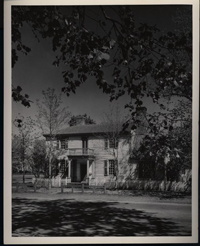

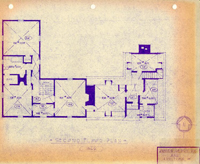

The present James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop is a large, frame, U-shaped building composed of three architectural elements. The south front, measuring approximately 68' 6", extends almost the full breadth of the lot.5 The expanse is an aggregate of distinct units: a dwelling and two shops. Though the size of the structure reflects three periods of eighteenth century construction, the building is a composite of restored and reconstructed entities. It has been restored to the period of James Geddy Jr.'s ownership of lot 161 (1760-1778).

The two-story, L-shaped James Geddy House, situated at the southwest corner of the property, was built ca. 1750 and is the only original building on the site.6 Its south facade measures 41' 2-5/8" along Duke of Gloucester Street and the west ell projects 40'½" toward the back of the lot. Two reconstructed one and-one-half-story shops, occupying original foundations, are attached against the east elevation of the house. The two-story house and the middle shop were built simultaneously in the eighteenth century. Since no Interior doorway initially linked them, the 16' x 16' one-room shop was in essence a separate building. The east shop is two rooms deep and has exterior dimensions of 15' 11" x 26' 7". Its south portion, a room corresponding in size to the middle shop (about 16' x 16'), was originally built prior to 1760. The shop was elongated in that year by the addition of a 15' 11" x 10' 8" room on its north elevation.

HOUSE HISTORY:

The existing James Geddy House was not the first colonial dwelling on lot Page 3 161. Vestiges of an early eighteenth-century structure, located near the southwest corner of the property, were discovered during archaeological excavation in 1967. The surviving foundation segments lie directly beneath and partially incorporated into the foundations of the extant James Geddy House. The appearance of the building can be generalized from archaeological evidence. Its dimensions were approximately 32' 6" x 20' 0". The foundation walls, laid in English bond, were 9 inches thick, indicating that the building was frame. Presumably it was a one-and-one-half-story structure. The interior arrangement could have consisted of one or two rooms and a passage on the first floor and an unfinished area or additional living quarters beneath the roof. A large exterior chimney was located at the east end of the building, (It is conjectured that portions of this chimney are still encased within the existing chimney between the Geddy House and middle shop.) An exterior fireplace, or forge, which seems to have been used for smithery, projected from the north side of the chimney. Its fireplace opening faced east, in the opposite direction of the interior hearth, Brick step foundations, remaining beneath the present south porch of the Geddy House, indicate that the entrance door was in the center of the street elevation. Fragments of a marl path terminate slightly east of center on the north side of the building, suggesting the occurrence of a back door in that location. The dwelling was enlarged at an undetermined date by the addition of a room, measuring about 16' 6" x 12' 6", at the northwest corner. A forge was subsequently built into the east wall of the addition.

Among the artifacts discovered in the context of these foundations were the residue of metal crafting and a ca. 1730 wine battle with the initials "JG" scratched into its surface. Archaeological evidence conclusively associates the building with the tenum of James Geddy, I,7 though it may have been built by an earlier owner of lot 161.8

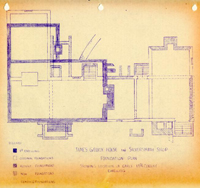

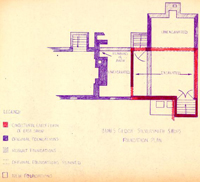

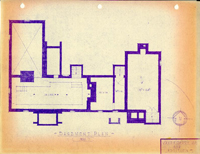

JAMES

GEDDY and SILVERSMITH SHOP

JAMES

GEDDY and SILVERSMITH SHOP

FOUNDATION PLAN

SHOWING LOCATION of EARLY 18TH-CENTURY

DWELLING

The precise construction date of the James Geddy House is unknown. On the basis of available information, it has been tentatively established that the dwelling was built ca. 1750. By the fall of 1760 the building seems to have been as large as the James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop is today. To determine the approximate age of the house and interpret the chronology of eighteenth-century changes to its appearance, it has been necessary to infer conclusions from archaeological, architectural and historical research.

James Geddy, Jr. bought lot 161 from his mother on August 18, 1760. The following month he rented the east end of a house, or tenement, on the property to Hugh Walker and John Goode, merchants. Walker and Goode had already "repaired and improved" the building at their own expense and proposed to enlarge it with a one-room addition. Consequently, with five shillings paid in confirmation of the agreement, the two men obtained a fifteen-year, rent-free lease. The deed of lease specified that:

... in Pursuance of an Agreement made between the Parties aforesaid the said Hugh Walker and John Goode at their own proper Cost and Charge have repaired and improved a Messuage house or Tenement Scituate and being on the north Side of Duke of Gloucester Street and are to Erect and Build a Shed to the same Sixteen feet long and ten feet wide with an out Side Chimney upon the Lot of Ground belonging to the said James Geddy where he now dwells which Lot is numbered in the Plan of the said city by the figures 161 ... the said James Geddy hath Demised, Granted and Letten and by these Presents doth Demise devise Grant and Lett unto the said Hugh Walker and John Goode part of the Messuage house or Tenement by them repaired and Improved as aforesaid that is to Say the East End or Room of the said house with the Chamber or Room over the Same and the Cellar under neath with the said Shed when built as aforesaid in the whole containing Sixteen feet in front and twenty Six feet in width with leave to Erect and Build an Outside Chimney to the back room or Shed also the free use of the necessary house and Well belonging to the said Lot ... 9Page 5

Walker and Goode were to occupy only part of the building. They leased the end of the tenement which measured 16' x 16' and included an east room, a chamber above the east room, and a cellar below it. The back room they intended to build was to be ten feet wide and sixteen feet long and was to have an exterior chimney. As Walker and Goode were merchants, they probably planned to operate a store in the rented space.

Foundations of an eighteenth-century building located near the southeast corner of the lot were excavated in 1954. From their appearance the foundations were irrefutably identified as those of the tenement described in the lease of 1760. The size of the brick walls coincided with the dimensions noted in the deed. Beneath the 16' x 16' south portion of the building was a full basement. There vas a 10' x 16' addition on the north side and an exterior chimney foundation located at the center of the addition's rear wall. (The reconstructed east shop was built over these foundations.)

Related documentary evidence indicates that Walker and Goode forfeited their lease before its expiration in 1775. Geddy continued to rent the tenement. In July, 1771 he advertised:

THE STORE, adjoining the Subscriber's Shop, lately occupied by William Russel, is to be LET, and May be entered on Immediately.10

Geddy vas evidently successful in finding a tenant, for in October, 1771 Mary Dickinson was operating a millinery shop "next door to MR. JAMES GEDDY'S Shop, near the Church, in Williamsburg."11

The connotations of the foregoing references are important. The agreement of 1760 rented "the east end or room of the said house", stating that Walker and Goode were granted only "part of the Messuage house or Tenement". William Russell occupied a store "adjoining" James Geddy's Shop, and Mary Dickinson was located "next door to Mr. James Geddy's shop."

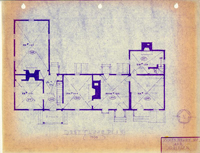

JAMES GEDDY SILVERSMITH SHOPS

JAMES GEDDY SILVERSMITH SHOPS

FOUNDATION PLAN

Archaeological investigation in 1967 proved that the two-story Geddy House and the middle shop were originally built concurrently. The foundations of the early colonial dwelling were reused as far as they extended, but new brickwork was bonded into the old walls in laying the foundations under the shop and the north ell of the house. Several continuous courses of brick were then laid on top of the united foundations to complete the height of the walls. The absence of a vertical joint in the upper courses of the north and south foundation walls at the point of conjunction between the house and shop means that those two parts of the building were constructed at the same time.

A vertical joint does occur in the original brickwork where the south wall of the east shop abuts the foundation of the middle shop. This condition verifies that the two shops were built at different times.

By co-ordinating the archaeological and historical information, it seems reasonable to assume that the Geddy House and both shops were in existence by September, 1760; that the north addition to the east shop was built shortly after September, 1760; that James Geddy, Jr. used the middle shop for his own silversmith trade; and that he rented out the east shop.

One clue hints that the east shop was an independent building before the Geddy House and middle shop were built. The position of a north/south foundation wall indicates that the basement under the east shop originally measured 16' x 20' rather than 16' x 16'. The cross wall stands about eight feet east of the chimney at the east end of the Geddy House. Between the cross wall and the chimney, the earth was not dug out for a basement in the eighteenth century, but an original cellar did extend from the cross wall to the end of the east shop. Another eighteenth-century foundation wall, which was removed in 1930, divided the area beneath the two shops in half. The cross walls stood about four feet apart. The placement of the subdividing walls suggests that the east basement was not coeval with the structural division of the shops into two equal rooms. The west cross wall possibly marks the end of a 16' x 20' shop or outbuilding located at the southeast corner of the property during the same period that the early/colonial building existed at the southwest edge of the lot. When the Geddy House and middle shop were built, the east building may have been incorporated into the new building. Two square shops, equally 16' x 16', could have been contrived adjacent to the two-story house by reducing the length of the east shop and erecting the 12' x 16' west portion of the middle shop.

Page 7The circumstance which most logically motivated the construction of the Geddy House was Anne Geddy's sale of lot 162 in 1750. While the Geddy family owned the whole block between Market Square and Palace Green (1738-1750), they may have lived on lot 162 and worked on lot 161. The necessity of consolidating their mercantile and domestic activities on a smaller acreage could have compelled the construction of new buildings on lot 161 or enlargement of ones already standing there.

The one direct eighteenth century reference to the construction of the Geddy House implies, however, that it was built much later than 1750. On May 2, 1777 James Geddy, Jr. entered an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette which read:

FOR SALE

THE houses and lot whereon I now live in Williamsburg, well improved, and the whole built within these few years; one fourth of the purchase money to be paid down, and the remainder at four annual payments. If not sold before the 10th of June next, they will be set up to the highest bidder,12

If the Geddy House was built ca.1750, the phrase "within these few years" would embrace a quarter of a century. Taken literally, the advertisement indicates that the Geddy House was built while James Geddy, Jr. owned lot 161. A preponderance of evidence, however, intimates that the dwelling was constructed before 1760. Unless additional information is found to resolve the ambiguity, the wording of Geddy's notice must be accepted as an exaggeration.

It might be contended that Geddy "well improved" a one-and-one-half-story house already situated at the corner of the lot by adding a second story to it or building the north ell as an addition. Tangible evidence disproves both these possibilities. The ell is an integral part of the building, not an addition. The structural framework is uniform in character and undeniably intended for a two-story, L-shaped house. The corner and intermediary posts are all eighteen-foot timbers, Page 8 spanning the full height from foundation to roof.

After James Geddy, Jr. moved to Dinwiddie County, Humphrey Harwood, a local carpenter, made repairs to the buildings on lot 161. Harwood itemized the account in his ledger. His notations reveal certain architectural features of the Geddy House as they appeared several months before Robert Jackson bought the property. Among Harwood's work were the following repairs:

1778 May 19th To 1700 bricks @ 5/6 32 bushs of lime @ 1/6. hare 1/6 £ 7. 3. 0 To Repairing Cellar wall 60/. 8 Days labr a 4/ 4.12.00 To Mendin plastering in D. House. Dary of landary 15/ 15. 0 To laying harth of mindg Chimney in Chamber 10/ 10. 0 To White Washing 7 Rooms 2 passages, 4 Clossets, & 3 poarches @ 7/6 4.13. 9 To Whiting Dary 2/6. of Mendg Kitchg & Layg harth 10/ 17. 6 July 2nd To Mortar of Repairin Steps 10/ 10. - £ 19. 1. 3 13

See - Robt. Martin's Accts. with Harwood Ledger B, p. 1 1782-1787

By the middle of 1778, the house had at least seven rooms, two halls, four closets, a basement and three porches. Brick steps led to an entrance door, one of the porches or a basement entrance. The interior walls were plastered and whitewashed. The house could not have been new, for a cellar wall and a second floor fireplace (in the "chamber") were in poor condition.

Several eighteenth-century changes were made to the house at undetermined periods. 1.) A door was inserted in the east wall of the house to connect the dwelling and middle shop. The doorway vas converted from an original closet located south of the fireplace. 2.) A low basement, only a few feet high, was dug beneath the north ell of the house. The bulkhead entrance was cut through the east foundation wall about three feet from the north corner. During the first decade of the 19th century the outside entrance was closed. 3.) A one-story shed-roof addition was built across Page 9 the north elevation of the house between the north ell and the north room of the east shop. The addition was built in two stages, with the first portion attached to the back of the two-story house. As the shed room covered the north bulkhead, a new basement entrance was built at the back of the addition. Whether these alterations were among James Geddy, Jr.'s "improvements" has not been ascertained.

Also - incidental Repairs & Implication of Geddy & Martin accts w/ Harwood for repairs in relation to 1777 Adv. for sale

The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg (ca. 1782) shows the Geddy House as a large, square building. The representation would be dismissed as an error if the unknown cartographer had not correctly depicted the L-shape of the house next door on lot 162 (see Page 11), It is unlikely that the Frenchman accurately observed the L-shape of one house and failed to note the other. Taking the north shed addition into consideration, a first floor outline of the building would appear nearly square when drawn in plan. The Frenchman's version of the Geddy House must be a rough sketch of its shape, after the construction of the north shed so it seems that the shed addition was in existence by the Revolutionary period.

But see Wren Bldg & others

During the late eighteenth century a second floor was added to the east shop. Nineteenth-century alterations completely transformed the appearance of both shops. A one-story brick addition was built at the back of the east shop in substitution of the room constructed in 1760 by Walker and Goode. The east shop was veneered with a false Victorian shop front, which completely disguised the intrinsic colonial core of the building. The middle shop was elevated to two-story height during the 1800's, making the shop appear an unbroken continuation of the two-story house. When the restoration of the Geddy House was first begun, the nineteenth-century portions were stripped from the building and only in the final stages of dismantling were the eighteenth-century structural remnants revealed. The eighteenth-century framing members that remained were salvaged for reuse in restoring the Geddy House.

FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP

FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP

PLAN

The original James Geddy House is an unusual example of eighteenth-century architecture in Williamsburg. The combination of a two-story elevation with an L-plan and a resultant corner-hipped roof distinguishes the design. The idea evidently was premeditated, for investigation of the structural framework verifies that the two-story dwelling was originally built as a whole. Perhaps the plan was a direct consequence of the location. In an effort to utilize the advantage of a corner lot and exposure along two of Williamsburg's prominent streets -- Palace Green and Duke of Gloucester Street -- it may be that the early builder conceived the design as a conscious adaptation to the surroundings. The recent discovery of original structural markings for a probable door on the west elevation, in the position of the present first floor middle window, emphasizes the possibility that the site influenced a dual orientation (even a double facade) for the building.14

It is significant that the antecedent of the Geddy House was an L-shaped dwelling (see Page 3). Although the plan of the early eighteenth- century house on lot 161 resulted from an addition, it plausibly exercised a direct influence upon the design of the Geddy House.

Available records show that there were apparently several other houses similar to the Geddy House in Williamsburg during the eighteenth century. Only one of these, the Powell-Waller House, has survived. In contrast to the Geddy House, it is a one-and-one-half-story structure that developed as an alteration. When the frame west ell was constructed in the eighteenth century to connect with an earlier brick dwelling, the A-roof of the first house was extended, with a hip at the north corner, to cover the addition.

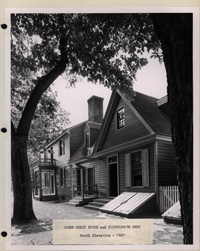

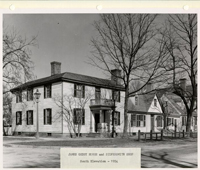

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE and SILVERSMITH SHOP

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE and SILVERSMITH SHOP

South Elevation--1967

A frame house which stood on the Norton-Cole lot until the first decade of the nineteenth century was also analogous to the Geddy House. Records prove that it was a one-and-one-half-story, L-shaped dwelling with a roof hipped at the southwest corner. It was oriented toward Market Square and Duke of Gloucester Street. Like the Geddy House, it seems that the structure was initially planned as an L-shaped unit. The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg clearly shows the contour of the house as it looked around 1782. In the early 1800's the east ell was torn down and replaced with the existing two-story brick dwelling. An L-arrangement was maintained since the brick Norton-Cole House was linked to the west portion of the first building. The present frame, story-and-a-half section facing Duke of Gloucester Street and the shop attached to its east end are reconstructions.

The historical correlation associating lots 161 and 162

increases the significance of an architectural correspondence between the Geddy

House and the

early dwelling on the Norton-Cole lot. Archaeological discoveries confirm the

concentration of extensive gunsmithing and brass founding activities on lot 161

before the middle of the eighteenth century (as well as during the Revolutionary

period) and suggest that the early eighteenth-century dwelling there may have

functioned exclusively as a shop at one time. The Geddys may have lived on lot

162 and worked on lot 161 while they owned the lots jointly. If so, they would

have resided in the early dwelling on the Norton-Cole from ca. 1738 to 1750.

Assuming that the Geddy House was built around the time that Anne Geddy sold lot

162 (1750), it is seems reasonable to conclude that its L-plan was substantially influenced by

the house the Geddys formerly occupied on the Norton-Cole lot.

Casey's Store, a colonial building no longer in existence, apparently bore the most striking resemblance to the Geddy House of any structure in Williamsburg. It stood on the northeast corner of Duke of Gloucester and Henry Streets until 1930, when it was removed in developing Merchants' Square, the modern Page 12 commercial district. Photographs and records made prior to its demolition reveal that the L-plan, the south and west elevations, the corner-hipped roof and the two chimneys of the building were comparable to features at the Geddy House. Though the superficial likeness is extraordinary, a satisfactory study of the relationship between the two buildings is inhibited by insufficient knowledge of the historical and architectural origins of both.

The facade of the original Geddy House is similar to those of several other two-story, eighteenth-century houses in Williamsburg. Three-bay compositions occur at the Semple, Carter-Saunders, Allen-Byrd (south elevation) and St. George Tucker houses. The arrangements are alike at these original houses: two windows flank a central doorway on the first floor and three windows occur on the second floor. The Geddy House composition is distinct in having a second-story doorway directly above the entrance door. The customary facade in eighteenth-century Williamsburg houses was five-bays wide.

Marcus Whiffin, in The Eighteenth-Century Houses of Williamsburg, cites another local comparison regarding the Geddy House. He states that "its low-pitched roof, without dormers, relates to the Archibald Blair and Peyton Randolph Houses, with which...it may be contemporary."15

The duality of the James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop would not have been unusual in the eighteenth century. The practice of maintaining domestic and craft operations in a single location, even within the same building, seems to have been common in colonial Williamsburg. Though no original structures of the type exist, the reconstructed George Jackson House and Shop, Anderson House and Draper House attest to similar house-and-shop arrangements.

RESTORATION:

The restoration of the James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop has been an intermittent program of thirty-eight year's duration. The-original building was restored in 1930. In 1954 the two east shops were reconstructed over original foundations. Preparation for opening the structure as an exhibition building was begun in 1966. Interspersed among the three major projects of restoration, minor modifications have been made to the building over the years. Though the restoration is essentially complete, several refinements are projected before the program is finished.

THE JAMES GEDDY HOUSE:

The Geddy House was one of the first buildings restored in Williamsburg. The initial restoration was comprehensive and only superficial changes have been made to the two-story house since 1930. Its eighteenth-century fabric was found virtually intact at the onset of restoration. Either the whole or a remnant of most architectural details remained in situ and, if too deteriorated for retention, did provide basis for accurate replacement. By estimation only about one-third of the total work demanded new material.

The condition of the house can be summarized in terms

of its eighteenth-century components. The foundations are original, though

extensively repaired. The brickwork of chimney stacks and gutters is new. The

lower portions of the chimneys are original, but patched. The flues are lined

with modern terra cotta. About eighty-five per cent of the structural framework

is original. Besides minor substitutions, most of the roof timbers and sills are

new members. The cement-asbestos roof shingles simulate eighteenth-century wood

shingles. The house is insulated with modern material. About one-half of the

exterior woodwork is original. On the south and west elevations, the cornice,

weatherboards, window sash and frames, shutters

Page 14

and cornerboards are original. Counterparts on the

north and east elevations are generally new features, designed to match the old.

Three window sashes, six window frames, three shutters and two basement grilles

and frames are reproductions. Ninety per cent of the window glass is original.

The front door and both first floor exterior door frames are new. The second

floor doorway on the south elevation is entirely original. The entrance porch

and the north bulkhead are reconstructed. The new north stoop is a temporary

feature. The exterior paint colors are not original to the Geddy House. The

interior architectural details are almost wholly original. All of the

eighteenth-century interior doors remain. The floors, with minimal patching, are

original. All the H-and-L door hinges and the floor nails in three second floor

rooms are original; otherwise, the hardware pieces are reproductions. The

stairs, except for the treads, are original. The woodwork is essentially

original, or old. One second floor mantel is a replacement. Four original

closets remain. New lath and plaster cover the walls and ceilings. The interior

paint colors match original samples.

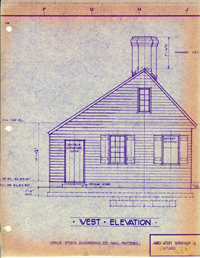

EXTERIOR:

The brickwork of the Geddy House required extensive repair in 1930. Modern stucco, which entirely concealed the exterior surfaces of the foundations and chimney stacks, had to be removed before the masonry could be patched. Approximately 8,400 eighteenth-century bricks (taken from the original foundations and other local sources) were relaid in the foundation walls. New bricks, selected to harmonize with the original bricks in size and color, were used for underpinning the foundations, for rebuilding the chimneys above the roof line, and for laying the gutters.

The foundations are laid in English bond. The house has

two interior chimneys: the west chimney is located between the south portion of

the building and the north ell; the other is situated at the east end of the

original dwelling. Both chimney stacks are

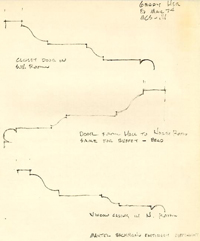

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

West Elevation-1967

Showing Probable Door Location

Page 15

laid in common bond. The original lower portion of the

east chimney (from the ground to the upper necking) is laid in English bond.16

The chimney caps, copied from the damaged originals, are of a typical colonial

design. They have a double projecting brick course supported by two corbelled

rows and are surmounted with a protective band of cement wash which simulates

eighteenth-century, oyster shell-lime mortar.

The type of ground gutter installed against the basement walls was used extensively throughout Tidewater, Virginia in eighteenth-century construction. The gutters consist of six rows of stretchers laid parallel to the building and one outside course of bricks set on edge. The stretchers are laid slanting toward the center. Similar original gutters, though typically not as wide as these,17 were found at the Dr. Barraud House, at the flanking buildings in the forecourt of the Governor's Palace and elsewhere in Williamsburg.

The majority of yellow pine structural timbers were sufficiently reinforced in 1930 with minor repairs and substitutions. The sills, however, were almost entirely replaced with new heart pine, pressure-creosoted members. The original corner and intermediary posts, corner braces and first floor studs were retained. On the second floor a number of studs were renewed. Two new wall partitions have been installed on the second floor since 1930.

An unusual roof shape results from the L-plan of the

Geddy House. The formation is actually a union of two perpendicular A-roofs,

joined by a hip where they meet at the southwest corner. A deep valley

consequently occurs at the north west corner and gable ends appear on the north

and east elevations. The low pitch of the roof signifies that the house dates

from the mid-eighteenth century, or later. The roof was entirely reframed in

1930, though a few original collar beams were renailed in place. A modern tin

roof covering, existing at the beginning of restoration, was supplanted with

square-butt, cement-asbestos shingles. The shingles are a modern, fire-resistant

product

Page 16

representing simulating eighteenth-century, hand-split, wood

shingles.

The building is faced with beaded weatherboards.

Two-directional corner-boards, finished with a bead at the corner angle, are

mounted at each corner. A full cornice, consisting of crown mold, beaded fascia,

modillion blocks, and bed mold, trims the eaves.18 The windows in the house are

double hung and of two sizes: those on the first floor have eighteen lights, but

fifteen-light windows appear on the second story. The diminution in size for the

second floor windows is an aesthetic detail. The sash muntins and two-member window

frames have typical colonial profiles. Most of the window panes are

eighteenth-century, hand-blown, "bull's eye" glass. Louvered shutters,

designed with center cross rails, flank the windows. They are secured against

the building with reproduction, rat-tail, wrought iron shutter stops. The pine

basement grilles are fashioned with three horizontal, square bars, framed

diagonally into a center stile and the jambs. The grilles are set within

single-member frames.

The three exterior doors are similar in design, but varying in size. Each door has six panels, the panel side out, arranged with two square panels over four rectangular panels. The doors are framed with three-member architraves. To sustain the wear anticipated after the house becomes an exhibition building, a cast iron plate was inset in the front door sill in 1966.

The Geddy House has been painted a number of times since its first restoration. The succession of colors has included coats of white, salmon and gray on the weatherboards with contrasting tones on the trim. A tri-color paint scheme was adopted in 1966, combining gray-green on the weatherboards, light gray on the trim, and red on the doors and window sash. The gray-green color was reproduced from an eighteenth-century paint sample disclosed at the Brush-Everard House. Traces of red paint on doors and window sash have been found at several eighteenth-century Williamsburg houses.19

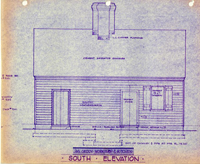

SOUTH ELEVATION:

The three-bay facade is composed of two windows ranged on either side of two Page 17 central doorways. The second floor windows and door are aligned exactly above those on the first floor. The effect is one of balanced scale and proportion.20

As noted above, the details of the south elevation are almost entirely original. Only the porch, front door, roof framing and shingles are new.

The character of the entrance porch was chiefly determined by evidence that the second-story exterior door was an original feature and by the discovery of outlines of halved newel posts and pilasters on weatherboards covering the south face of the building. Though similar in design to a nineteenth-century porch it superseded, the new porch was based on an example existing in Williamsburg. Architectural precedent was taken from the entrance porch at the Semple House, using eighteenth-century builders' handbooks as supplementary reference. The classical details of both porches reflect the pervasive eighteenth-century interest in Greek and Roman cultures.21 Colonial builders were eclectic in copying English and Italian variations of ancient architectural motifs and often indiscriminately mingled aspects of the different orders. The Geddy House porch represents a typical vernacular adaptation of the classical idiom. In contradiction of strict classical rules, fluted Doric columns and pilasters are used in combination with an Ionic pulvinated frieze. A reproduction wrought iron handrail extends between the two columns at the south side of the porch.

The occurrence of a doorway on the second floor, leading to a balustraded porch, is unusual in eighteenth-century architecture. A detail of the doorway--the four-light transom above it;-is not an uncommon feature in Williamsburg, for many original examples have been found in local eighteenth-century houses. This, however, is the sole instance of an original second-story transom. Two conditions justify the location and use of the Geddy House transom. As a design feature, it allows continuance of the door trim up to the bottom of the cornice, exactly in line with Page 18 the tops of the second floor windows. Functionally, it provided an exterior light source for the original second floor passage, which was window-less.

In 1931 the sheathing around the entrance door was modified. To accentuate focal emphasis upon the doorway, the beaded weatherboards within the inner porch perimeter were overlaid with flush, random-width, quarter-inch beaded boards.

WEST ELEVATION:

The west elevation is the longest side of the original building. It is virtually unadorned and is relieved only by six windows. The three second story windows are directly above those on the first floor. The fenestration is uneven, but the spacing was an unavoidable consequence of the chimney location and interior plan. The pair of south windows is widely separated from the four north windows. From the interior it can be seen that the north windows were placed symmetrically in the rooms they light. The south windows were pulled as far as possible toward the back walls of the first and second floor southwest rooms in order to diminish the gap between the three sets of windows and improve the exterior appearance. The first floor middle window on this elevation may have originally been a door. (see page 10).

Three Several minor details on the west elevation were

missing in 1930. The south basement grille and frame are new. Two shutters are

replacements (the south shutter on the first floor south window and the south

shutter on the second floor middle window). As already noted, the roof framing

and shingles are substitutions. otherwise the features are original, or at least

old.

NORTH ELEVATION:

Because of the L-plan, the north elevation of the house has two sections: the north end of the ell and the north side of the arm of the building that lies parallel to Duke of Gloucester Street. Most of the eighteenth-century features on the north side of the house had disappeared by 1930. The cornice, weatherboards and Page 19 cornerboards are duplicates of originals on the south and west elevations.

NORTH ELL: The gable end of the roof appears on this elevation. A heavy, nineteenth-century molded cornice, returned at both ends, was mounted along the roof line when restoration began. The original rake boards, tapered and beaded on the lower edges, were found in place under the cornice; they were repaired and retained. Curved end boards copied from typical colonial models, were applied against the ends of the east and west cornices. Two windows occur in the center of the elevation. Both window frames and the lower window sash are new. The basement grille and frame are also reproductions.

insert "South Portion" from p 20

EAST ELEVATION:

Like the north elevation, this elevation has two separate portions: the east side of the north ell and the east end of the south arm of the house. As stated before, the cornice, weatherboards, cornerboards and chimney stack are copies of surviving original features. The roof framing and shingles are new.

NORTH ELL: When restoration began, there were only two windows, located near the north corner, on this elevation. Both were in such poor condition that only the sash of the second floor window were retained. Two new windows were installed near the south corner. Investigation in 1967 revealed that the first floor south window was unsubstantiated by framing marks, so it has been removed. The authenticity of the second floor south window is questionable.

A bulkhead entrance was cut through the foundation wall near the north corner during the last quarter of the eighteenth-century. The bulkhead was apparently abandoned within a few decades and has not been honored with a reconstructed feature.

louvre: attic ventilation

EAST END: The rake boards here are copies of original ones found on the north elevation of the ell. The original east chimney rises against this elevation. The chimney stack alone is unobscured, for the middle shop is attached to the east Page 20 end of the house. (See page 29 for discussion of the middle shop.)

Put on p. 19

SOUTH PORTION: This elevationsection has Two windows and a door penetrate. The frames and sash of both windows are new. The doorway, which has a new

frame, is unusually low. The door opens directly under the stair landing in the

first floor passage, where the height of the landing allows only a six-foot

clearance for the door. It is Interestingly that the second floor structural timbers above the door

are framed for the inclusion of a window that was never inserted.

A bulkhead, validated by archaeological evidence, was added near the east corner in 1930. It is a sloping bulkhead, typifying the sort that was prevalent in Virginia in the eighteenth-century. The only access to the basement beneath the original house is through this entrance.

An open shed-roof porch, occupying the angle between the north and south projections of the house was built in 1930. (The longest dimension of the porch was attached against the east elevation of the ell. It was approached by wood steps at the north end.) Though arbitrarily constructed for practical reasons,22 it was copied from a porch at Fauntleroy, near Aylett, King William County, Virginia. It was removed in 1967 because recent archaeological findings determined that a porch of this kind did not exist during the colonial period. There is proof that an eighteenth-century shed-roof addition did extend across the north elevation in an east/west direction, so an appropriate feature will be reconstructed after further research. A temporary wood stoop (like the one at the back of the middle shop) will suffice until the authentic addition is rebuilt.

INTERIOR PLAN:

The plan of the Geddy House, despite its L-shape, is

not completely antithetic to typical eighteenth-century prototypes. Its

intrinsic asymmetry is incompatible with eighteenth-century concepts of ordered

and balanced proportion,

Page 21

but the interior spatial divisions follow customary

patterns. The original layout of the two floors was identical. Each Both storyies had

three rooms grouped around a central stair passage. The first floor rooms, which

will be open for exhibition in the summer of 1968, have been named the Counting

room (north southeast room), the Passage (southwest room), the Chamber (southwest room) and the

Hall room (southeastnorth room). The second floor will not be open to the public. The rooms

there were probably chambers, or bedrooms, originally.

Several changes were made to the floor plan in the

early 1900's prior to the acquisition of the house for restoration. In reverting

to the original plan, one modern partition which subdivided the first floor

north room into two rooms was taken out and three similar partitions in the

second floor north room were removed. Slight rearrangement of the second floor

was necessary to include bathrooms. In 1930 a stud wall was erected across the

south end of the north room, providing a bathroom between the two rooms on the

west side of the house. Unfortunately, the alteration relegated the north room's

fireplace to the bathroom. Several years later another bathroom was added to the

second floor by partitioning off the south end of the passage. The fixtures of

the second bathroom were removed in 1966, but the wall was left standing. No

actual changes were made to the floor plan in 1966; however, all but two of the doors

opening into the second floor passage however,were permanently sealed in

compliance with fire regulations. One new door was cut through the north wall of

the second floor southwest room.

The interior fabric of the structure was essentially

intact in 1930 and minimal refurbishing was necessary to restore its original

appearance. Original pine floorboards remained in every room and patching was

requisite in few instances. Reproduction cut nails, duplicates of an

eighteenth-century type, were used in the rooms where original nails did not

exist. All other hardware, except the H-and-L door hinges, had to be replaced

with suitable reproductions. Original or old woodwork was

22

extant in each room, surviving in a condition

necessitating little carpentry. The interior trim of the Geddy House was found

to be simple in design and execution and modest in quantity. Beaded baseboards,

encircling each room, were painted black. The door and window architraves,

consisting eitherof two or three members, were of similar character throughout

the house. The original doors (mostly six-panel doors) required rehanging and

patching of the rails where unauthentic locks had been mounted. The hearths and

supporting brick arches were relaid. New plaster fireplace surrounds were

applied and painted black, as was customary in the eighteenth-century. Colonial

lath and plaster still covered the walls and ceilings in 1930, but were too

inferior in

condition to be kept. The new lath was metal. Though constituted of modern

materials, the plaster was trowelled unevenly to simulate the rough texture of

eighteenth-century oyster-shell lime plaster. The white paint for all walls and

ceilings was a modern product representing approximating whitewash. Interior paint colors were selected to

match original hues revealed in investigation of the woodwork. The house was

equipped with contemporary heating, plumbing and electrical facilities.

Since 1930 changes to the interior have been trivial ones, made generally in the nature of maintenance. In 1966 the obtrusive modern conveniences on the first floor, such as light switches, base plugs and heating outlets, were concealed where possible. This was done only in areas to be opened for exhibition. The house was also equipped with air conditioning at that time.

The ceiling heights in the Geddy House are approximately nine feet on the first floor and seven feet on the second floor.

BASEMENT:

The original basement was small, comprising part of the

area below the first floor stair hall and southeast room. It extended from the

east end of the house to a cross wall situated slightly east of the east

foundation of the north ell. The north

BASEMENT PLAN

BASEMENT PLAN

900

JAMES GEDDY HO. AND ADDITION

Page 23

segment of the cross wall, which was all that remained

in 1930, was removed during restoration. The earth was then dug out below the

first floor southwest room creating a full basement under the south portion of

the house. Currently the cellar is filled with mechanical equipment.

A shallow cellar was excavated underneath the north ell in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, but was in-filled in the early 1800's. In 1930 a concrete floor was poured there. The crawl space under the ell is about three feet high.

FIRST FLOOR:

Southeast room (Counting Room): The room is lit lighted by

two windows, located

centrally in the north and south walls. There are two doors, both near the south

corners on the east of and west sides of the room. The southeast door which is not

original, was inserted at an uncertain date (possibly during the eighteenth

century) in place of an original closet beside the fireplace. A chair board,

beaded on the top and bottom edges, encircles the room. The mantel piece

consists of a three-member architrave set on beveled plinths and mounted against

a flush board backing. The mantel shelf, a detached member applied at the upper

edge of the board backing, has moldings reminiscent of an exterior cornice. It

is returned at either end and trimmed with dentils. Most of the dentils were

missing in 1930 and their replacement was guided by marks in the paint. The trim

is painted gray.

PASSAGE:

The Passage, like the southeast room, has a chair board in lieu of a chair rail. Original beaded cornerboards protect the plaster at all external angles. Five doors open into the passage: two from the exterior and one from each of the first floor rooms.

The narrow, U-shaped stairway is finished in a

conventional eighteenth-

FIRST FLOOR PLAN

FIRST FLOOR PLAN

1300

Page 24

century manner. It is a closed string stair. The first

run rises against the east wall, terminates in a cantilevered landing that

extends almost the full width of the stair hall, and the second run continues in

reverse direction to the upstairs passage. Except for the treads, the stairs are

entirely original, The turned balusters have a typical eighteenth-century

profile, as do the square, flat newel caps which rest atop unpaneled, square

newel posts. The profile of the stair rail repeats that of the newel caps. The

stringers, beaded on the upper edge, match the baseboards in the house. A curved

end board, similar to those normally found trimming exterior cornices, is

mounted on the string board behind the base of the newel post at the termination

of the second run. A nineteenth-century wrought iron hook, for the support of a

light fixture, was found in the soffit of the second floor newel in 1930. It was

replaced with a suitable eighteenth-century facsimile. The most unusual stair

detail is the second floor outer newel, which rises from floor to ceiling. The

square portion at the bottom is topped with a turned post. Marcus Whiffen, in

The Eighteenth-Century Houses of Williamsburg, cites this feature as speculative

evidence for an early eighteenth-century construction date for the Geddy House,

pointing out that it "is a throwback to the scheme from which English open

well stairs evolved..." It may be that the newel post was reused from an earlier

building on the site. At Walnut Valley in Surry County, Virginia, the same kind

of original newel is still in existence.

A closet originally existed against the north wall of the passage under the stairway. The space was converted to a basement staircase prior to the restoration and because of its usefulness, was not changed in 1930. In 1966 the area was rebuilt as a closet.

Woodwork is painted the same color gray as used in the

Southeast room.

SOUTHWEST ROOM (CHAMBER):

Purchased by John Christoffel (ca. 1968). [Demolished 5/31/68] (Bl. 36, #9)

This is the only room in the house decorated with a chair rail, cornice and dado. The cornice is not an elaborate feature, as it has only a crown mold, beaded fascia and soffit. The break in the cornice over the mantel was effected to conceal the brick arch supporting the hearth in the room above. The dado has raised panels of varying sizes, some of which are replacements. The mantel, which has a new shelf, is similar to a marble mantel formerly at Wheatlands and also black marble mantel in Wetherburn's Tavern (storage) which was original to Chiswell House in Williamsburg.(North Henry Street) NB Its moldings are of a character usually executed in marble rather than wood. It is possible that the mantel was originally intended to be marbelized, though no traces of such painting were found. The origin and connotation of the name "E-Shield", carved crudely in the upper left side of the architrave, are unknown. The woodwork is painted gray, a slightly darker color than appears in the passage and southeast room.

An original closet remains in the north wall, west of the fireplace. Its six-panel door and the door in the center of the east wall (opening into the passage) are the only two doors in the room. One window is located in the middle of the south wall and another is situated in the west wall close to the north corner (see Page 16).

NORTH ROOM (HALL):

In the north room the cupboard, or closet, is the only unusual decorative detail. The cupboard was undoubtedly converted from an original closet like the one behind it (in the southwest room), using woodwork from another source. The date of the alteration is ambiguous. A door architrave, resting on beveled plinths, surrounds the cupboard. Its upper portion is set within a window frame; the pulley blocks and sash grooves still remain in the pulley stiles. The inner architrave in the upper part is an arch, trimmed with two crude pilasters and a keystone. The arch enframes three butterfly shelves, which are built against a vertical board backing. Two paneled doors are fitted below the arch and the space between is finished with a molding resembling a chair rail segment. The makeshift Page 26 quality of the cupboard implies that it is a product of carpenter construction. Two similar eighteenth-century cupboards exist at the Benjamin Waller House, flanking the fireplace in the west wall of the northwest (living room). Like the Geddy House cupboard, those in the Benjamin Waller House resulted from alteration. During the restoration of Bassett Hall, the remains of a related closet were discovered in the studding of the northwest (living) room. Framing and paint marks revealed that its character was nearly identical to the design of the Geddy House cupboard, which served as reference for its restoration. (e.g.) Griffin House

The door from the Passage is located in the south wall

at the corner opposite the cupboard. Unlike the other six-panel doors in the

house, this one has four-panels. The fireplace is also in the south wall of the

room. The mantel, which is very much like the one in the first floor southeast

room, is not spaced equidistantly between the door and the cupboard, but is

off-center to the east. A two-member architrave surrounds the fireplace opening.

Another molding extends from either side of the mantel shelf to and terminates on

rectangular plinths at the base. The dentils below the mantel shelf, as in the

case of the mantel in the southeast room, were largely missing in 1930 and were

replaced according to paint marks. The woodwork in the room is painted tan, a

tone which tends toward an ochre shade.

The room was never trimmed with cornice, chair rail, chair board, dado or paneling. It has been conjectured, from the absence of woodwork, that the walls were originally papered. The Curator's Department has recently hung antique wallpaper in the room.

The room has four windows: two on the west wall, one at

the north end, and one in the east wall. A south window in the east wall, added

in 1930, was deleted in 1968 (see page 20). As already noted, the southwest

window may be a conversion of an original doorway (see Page 10). The depth of

the reveal of the north window shows that the end wall is thicker than others in

the house. It was

SECOND FLOOR PLAN

SECOND FLOOR PLAN

1360

Page 27

furred out in 1930 for the accommodation of heating

ducts.

SECOND FLOOR SOUTHEAST ROOM:

The room is almost

identical to the one below. It does not, however, have a chair board. The

mantel matches the one in the first floor southeast room with two exceptions:

the architrave has two members instead of three and the missing dentils below

the mantel shelf have not been replaced. Since the room is on the second floor

and not subject to general view, it was felt unnecessary to reproduce the

dentils. The board-and-batten door south of the fireplace was added in 1930 when

a closet was built into the room. The closet was removed in 1954 to provide an

entrance to the room above the middle shop. The door at the southwest corner was also

also added in the 1950's. The original doorway is in the west wall, but the door itself (an

eighteenth-century door) was taken from an unauthentic partition in the first

floor north room in 1930 and rehung here. The floor nails are original. The

paint color on the trim is gray.

Passage: The second floor passage is narrower than the

one on the first floor, because it was shortened in 1950 by a partition across

the south end, it is smaller than its original size. These conditions and the

absence of any exterior light source make it a dark, cramped hallway. The

original attic scuttle is located near the southwest corner; when the a new scuttle

was built in the north room, this one was permanently sealed. The gray paint

color is the same that is

used on the woodwork in the first floor Passage.

SOUTHWEST ROOM:

The East/West dimension of this room is slightly larger greaterthan that of the one below itof the first floor S.W. room. Instead of a mantel

piece, an original molded mantel shelf is set above the fireplace. The original

fireplace opening was smaller largerthan it now appears; the disparity between its

width and the size of the hearth shows the extent of the reduction. The closet

west of the fireplace is original, though the door in its

Page 28

back wall, connecting the room with the bathroom, is

not. A new door was cut through the east wall in the 1950's and in 1966 another door

was inserted beside the fireplace in the north wall. The original door is

approximately in the center of the east wall. The floor nails are original. The

woodwork is painted a dark beige.

NORTH ROOM:

Because of the provision of a bathroom at

its south end, this room is appreciably smaller than it was originally. The

closet and doorway in the southeast corner date from 1930, though the door is

original to the north

room. An attic scuttle in the closet ceiling was added in 1930. The baseboard on

the south wall is new. The floor nails are original. When the house is opened for

exhibition, this room will be used at asthe hostess room. The trim is painted the

same dark beige that is in the southwest room.

BATHROOM:

The window architrave and the baseboard on

the south wall are the only original trim in this room. All other features are

new. A short Passage east of

the bathroom was built in 1966 to connect the bathroom and southwest room with

the second floor Passage. The woodwork is paintedblueish-gray.

MIDDLE SHOP:

The Middle Shop is a one-and-one-half-story, one-room frame building confined between the original Geddy House and the reconstructed east shop. It faces Duke of Gloucester Street. Although it is a subsidiary of the Geddy House, it stands as an independent architectural element.

The shop was rebuilt in two stages. Its west portion, measuring 12' x 15', was reconstructed in 1930. The shop was enlarged to its present size (and accurate eighteenth-century dimensions) in 1954. It now measures approximately 15'11" x 15'11". Its appearance was modified in 1966 to return the building to its original character as a Silversmith Shop.

RECONSTRUCTION:

When restoration of the Geddy House began in 1930, the east end of the building (a two-story section beyond the east chimney) was believed to be a nineteenth-century addition. In the process of dismantling the segment, its one-and-one-half-story, eighteenth-century nucleus was found (see Page 9). At the time, it was thought that the colonial portion was a domestic wing of the Geddy House and not until several years later was its original shop function interpreted from historical records. Enough structural evidence remained to verify the original form of the structure, but its eighteenth-century components were inadequate for restoration.

The exact dimensions of the shop were deduced from the extant foundations. The wing, however, was only partially reconstructed in 1930. Its east end was aligned over the north/south foundation wall located about eight feet east of the original dwelling's east chimney (See Page 6). The original brick pattern, English bond, was readily evident and was matched in repairing the south and west foundation walls. (The west foundation is the east wall of the Geddy House.) The north and east foundations were entirely rebuilt. Ground gutters, like those around Page 30 the Geddy House, were laid on the north and south elevations. No basement originally existed under the 12' x 15' portion of the shop, so the ground was left unexcavated. (See Page 6). Structural markings encased within the section authenticated the shop's eighteenth-century characteristics. The pitch for the A-roof was established from an outline of the original roof peak discovered on the east face of the east chimney. The sash design was derived from eighteenth-century sash remnants unearthed beneath the floor of the razed portion. In general, the exterior details were copied from the Geddy House. Precedent for the box cornice was taken from an eighteenth-century cornice at the Moody House. The materials used in the reconstruction were new, except for scattered structural timbers and window panes and eighteenth-century floorboards salvaged from the dismantled east end and from diverse local sources.

EXTERIOR:

The exterior of the wing was faced with beaded

weatherboards. Cornerboards like those on the Geddy House were installed. End

boards, cut to follow the profile of the cornice, were mounted on the east and

west elevations. As the original roof ridge extended in an east/west direction,

only the east gable end was visible on the reconstructed wing. Tapered rake

boards, similar to original ones found on the north ell of the Geddy House, were

affixed along the east roof line. Square-butt, cement-asbestos shingles were

used as roof covering. An eighteenth-light window, matching the first floor

windows in the original house, was installed in the center of the south

elevation. Its louvered shutters were reproductions of originals on the Geddy

House. A basement grille was centered below the window. The back door vas placed

in the middle of the north elevation. The door was designed with nine window

panes over four panels. A simple wood stoop, classified as a adaptation based on

colonial details, was

Page 31

constructed in front of the door. Colonial Williamsburg

has designed a series of similar stoops for the convenience of modern residents.

A four-light window was placed east of the north door. An identical window was

inserted on the east elevation for attic ventilation.

INTERIOR:

The first floor interior was fitted as a modern kitchen. Eighteenth-century pine floorboards were laid, but all other architectural features were based on colonial precedent. A 3' x 4½' pantry was created on the west side of the room in the location of an original closet which has been converted to a doorway before 1930. A new closet was built on the north side of the chimney. The space under the roof was left as an unfinished storage closet.

In 1936 a one-story "lean-to" was built on the north side of the wing. It measured about 11½' x 11½' and contained a maid's room, bathroom and passage. Though loosely based on eighteenth-century precedent, it was an unauthentic feature. The addition was removed in 1954.

ENLARGEMENT:

The middle shop was amplified in 1954 to reinstate its

accurate original size. The east end was lengthened by about three feet and a

full basement was dug beneath the shop. Several changes were made to the

exterior. A new east window matching the one in place, was inserted on the south

elevation. Beneath it was added another basement grille. An uncovered wood stoop

was replaced on the north elevation. (The one built in 1930 was removed in 1936

when the "leanto" was constructed.) A sloping bulkhead, exactly like

the one on the north elevation of the Geddy House, was put at the northeast

corner of the shop. The roof covering was changed to round-butt, cement-asbestos

shingles. Two gable

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE

South Elevation-Restored

1930

Page 32

dormers were framed into the roof: one dormer was built

in the center of the south r slope; the other was added on the north elevation.

The details of the dormers include tapered rake boards, flush boarded tympana,

diagonal, beaded flush boards covering the cheeks and fifteen-light, double-hung

sash. Similar original A-roofed dormers are found at the Dr. Barraud, Braken and

Coke-Garrett houses. As a result of the alteration, the floor area was increased

in the modern kitchen on the first floor of the shop. The second-story room was

finished with typical colonial details and connected to the original house as a

bedroom.

REVISION:

After the decision to include the James Geddy House and Silversmith Shop in Colonial Williamsburg's expanded exhibition program, the two east shops had to be transformed to their original shop appearance. The buildings were adapted for residential use when reconstructed in 1954.

EXTERIOR:

As part of the 1966 project, several features were altered on the exterior the middle shop. The west window on the south elevation was converted to a rectangular bay window, copied from an original shop window at the Printing Office.23 Bay window were typical features of shop buildings in the eighteenth-century. The window was topped with a pediment gable, harmonizing with the gable end of the east Geddy Shop (see Page 55). The use of a pediment as a window detail denotes a late eighteenth-century embellishment. The motif occurred frequently in Southern and New England architecture and original examples are found, for instance, at the Edward Dexter House in Providence, Rhode Island, the Governor Woolcott House in Litchfield, Connecticut, and the William Gibbs House in Charleston, South Carolina. The projection of the Geddy House bay window allows sash and glass on three sides: the front has twelve lights and each side has a vertical row of four panes. To enclose the three sides of the shop window, four-valve paneled shutters, hinged and secured with a wrought iron Page 33 bar, were fashioned following a model at Port Royal, Caroline County, Virginia. The profile of the shutter panels was copied from shutters that were placed on the southeast window of the east shop in 1954. For reasons of security, paneled shutters were commonly used on shops and stores in eighteenth-century Williamsburg. The east window on the street elevation of the middle shop was changed to a door in 1966. A wood stoop, like the one on the north elevation, was constructed in front of the door-way.

A wood gutter was suspended from wrought iron straps against the cornice on the north elevation. The occurrence of wood eaves gutters in eighteenth-century Williamsburg has been documented, but examples are rare.

A roughly finished, pine fire ladder was installed on the roof of the shop. It was reproduced as a double ladder and, straddling the roof ridge, it has rungs on both the north and south roof slopes. Fire ladders were liberally scattered throughout Williamsburg in colonial times. A French traveler commented in 1781 that "upon [nearly all] the roofs are to be seen fire ladders."24 The purpose of the ladders was to provide speedy access to roof fires ignited by chimney sparks falling on the combustible wood shingles. The ladders were permanent, though moveable, features and could be reached by secondary ladders on the ground or from second story windows.

The exterior of the middle shop was repainted in 1966 with the same three colors used on the Geddy House: gray-green, light gray and red (see Page 16).

INTERIOR:

Changes to the first floor room in 1966 involved

removal of the modern kitchen fixtures and installation of authentic shop

furniture. Architraves for the

new door and shop window in the south wall were copied from original examples in

the Geddy House. The other basic trim was already of appropriate colonial

character. The woodwork in the room was painted a pale green color. Shelves were

fitted into the

34

the shop window for the display of silversmith wares.

Two walnut hanging cabinets were designed according to eighteenth-century

precedent and mounted on the east and west walls. The doors across the front of

both cabinets were finished with glass panes. Two jeweller's benches and

a draw bench, pieces of moveable furniture, were reproduced for the room. The

poplar jeweller's benches have heavy, kidney-shaped, gum tops and are fitted

with leather aprons. Eighteenth-century prototypes were reference for the design

of the work benches. Diderot's The Book of English Trades Diderot's Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire [illegible] des [illegible] Arts des [illegible], published in London in

1821 Paris in 1762, contains drawings

of similar benches.25 The furniture was given a natural wood

finish , except that the lower portions of the work benches were painted pale green.

No attempt was made to complete the second floor with authentic appointments. Modern cabinets, shelves and work benches were built along the walls of the room, so that it could be used for storage when the shops become craft exhibitions.

EAST SHOP:

Reconstruction of the east shop was implemented in

1954. The shop was rebuilt as a one-and-one-half-story, frame structure two

rooms deep in plan. In conformity with the original foundations, its outside

measurements are approximately 16' x 26'. The shop stands at the southeast

corner of the lot, within five feeta foot of the east property line. It and fronts on Duke of

Gloucester Street. Though incorporated into the entire building, it is, like the

middle shop, an independent entity. The east shop is the part of the building

construed as the "east end" described in the lease of 1760.

RECONSTRUCTION:

The original foundations, in conjunction with the 1760

deed of lease, revealed many fundamental aspects of the original shop.

Specifically authenticated were the dimensions of the shop and its rooms, the

circumstance of a north addition, the size of the basement, the locations and measurements of the north chimney

and

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE and SILVERSMITH SHOP

JAMES GEDDY HOUSE and SILVERSMITH SHOP

South Elevation-1954

35

south bulkhead, the bond of the foundation brickwork,

and the placement of stone steps on the south elevation. Otherwise, the design

of the shop was based on typical eighteenth-century precedents. New materials

were used in the reconstruction.

EXTERIOR:

The foundation walls were rebuilt in English bond.

Beaded weatherboards were

used as facing. The cornerboards were replicas of originals on the Geddy House.

Indicative of original eighteenth-centuryalterations at different periods, the south

cornerboard between the two shops was left in place and cornerboards were

applied on the east and West elevations about ten feet from the north end. The

same profile of the box cornice on the intermediary shop was carried over to the

new cornice. The end boards on the north elevation were transposed from the east

end of the middle shop.

The ridge of the A-roof was set at right angles to the roofs over the Geddy House and middle shop; consequently, the gable ends were oriented to the north and south. Tapered rake boards were mounted along the north roof line. On the south elevation a pediment gable was created by continuing the box cornice along the roof eaves and horizontally across the front of the shop. The tympanum was finished with horizontal, beaded flush boards. A similar pediment gable facing Duke of Gloucester Street occurs on the original, brick Prentis Store. The Geddy Shop roof was covered with square-butt, cement-asbestos shingles. Two dormers, exactly like the ones added to the middle shop, were framed into the roof on the east elevation; another dormer was built into the west roof slope.

Two features on the south elevation, the stone steps and the bulkhead, were confirmed by archaeological evidence. The sloping bulkhead was modeled after the one reconstructed on the north elevation of the Geddy House in 1930. American cut stone, a blue stone with split face approximating English stone imported in the eighteenth-century was used for the steps. The stone segments were arranged with a return on 36 the west side and were secured together with mortared joints and wrought iron cramps imbedded in lead. The steps were abutted against the bulkhead on the east side. An eighteen-light window, duplicating the original first floor windows in the Geddy House, was placed near the southeast corner. In contrast to the original louvered shutters on the Geddy House, paneled shutters were installed. Similar three-panel shutters are found at Wales in Dinwiddie County, Virginia. A twelve-light, double hung window, without shutters, was inserted in the tympanum near the roof peak. The front door was put on the west side of the south elevation. It was enframed within a three-member architrave and decorated with a four-light transom. The design of the doorway aesthetically links the original house and the shop, for it relates to the second story doorway on the south elevation of the Geddy House. The feature is typical in the locality; at least twenty original doorways with overhead transoms exist in Williamsburg.

On the west side, the south portion of the shop was attached to the middle shop. This left only the west elevation of the north room visible. A ten-light window, with a board-and-batten shutter hinged at its south side, was framed into the north room's west wall. An identical window was placed opposite on the east elevation. Below the east window a basement grille was built into the foundation wall. A wood gutter on the west elevation was joined to the gutter at the back of the middle shop.

An exterior chimney was replaced over original foundations at the center of the north elevation. Its lower portion was laid in Flemish bond and the T-shaped chimney stack was laid in common bond. The chimney cap differed slightly from the original design of the ones on the Geddy House, though it followed a common colonial pattern. Above the band of cement wash, a single row of bricks was set at the top of the cap. Casey's Gift, an eighteenth-century building formerly in Williamsburg, had identical chimney caps, which served as precedent for a number of reconstructed chimneys in town.

INTERIOR:

The interior of the shop was arranged as a modern residence in 1954, though the architectural features were based on colonial details. Eighteenth-century pine floorboards were used. Though they shared a common wall, no connection was provided between the larger house and the east shop. The shop was planned as a detached dwelling.

REVISION:

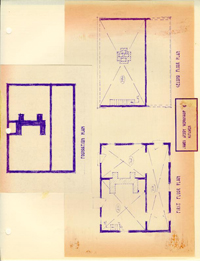

Few exterior modifications were requisite in preparing the east shop for exhibition in 1966. The stone steps in front of the south door were rearranged, omitting the return. A wrought iron hand rail was added on the west side of the steps. The alteration to the steps is evident in the sliced cramps which remain on the east and west sides. The hand rail reflects the design of the wrought iron railing spanning the south end of the Geddy House entrance porch. A sign for the Geddy Silversmith Shop was influenced by shop signs depicted in various eighteenth-century prints. It was copied specifically from a silver cup made in London, ca. 1738, by Peter Archambo. The chalice is owned by Colonial Williamsburg and is displayed at Craig's Golden Ball. Signifying James Geddy, Jr.'s., ownership, the sign was inscribed with the initials "I.G." It was mounted on the cornerboard between the two shops. The exterior paint colors used in 1966 on the Geddy House were repeated on the east shop.

Because no pretense was made in 1954 to reinstate the

east shop's original

interior shop arrangement, the floor plan was wholly remodeled in 1966. An

archetypal eighteenth-century shop plan is illustrated in Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises, published in England in 1703.26 The plan is rudimentary and

presents the essential attributes of a well-organized shop. It consists of a

front, sales room supplemented with a rear work, or counting, room. The

back room only is heated with a chimney. Archaeological investigation of the east

shop's foundation clearly showed that its plan resembled Moxon's pattern, as did

many of Williamsburg's eighteenth-century

PLAN of SHOP or STORE

PLAN of SHOP or STORE

Joseph Moxon

Mechanick Exercises

London, 1703

38

shops. In renovating the east shop, the first floor

south room abovealone was returned to authentic shop appearance. The first floor

north room and the second floor were equipped with facilities for back-up

silversmith activities. Two doorways were cut through the east wall of the shop

(one on each floor) to give access to the rest of the building. The stairway was

put in the north room.

The side walls of the south room have no windows and

are sheathed with horizontal boarding. A similar sheathing is original to the

first floor southwest room of the Market Square Tavern, Shelves, counters and

cabinets were designed on eighteenth-century basis and installed along the

north, east and west walls. Shelves were also fitted inside the southeast

window. The woodwork was constructed of pine, poplar and gum and painted pale

green. The gum counter tops were given a natural finish. A false scuttle was

built into the ceiling near the north wall and a ladder attached beneath it. The

exigencies of modern safety and utility required the inclusion of an actual

stairway in the building, but it was considered suitable to include the scuttle

in the exhibition room since it would have existed thereoriginally.

OUTBUILDINGS: