Courthouse of 1770 Architectural Report, Block 19, Building 3Originally entitled: "Order in the Court:

Recommendations for the Restoration of the James City County/Williamsburg Courthouse"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1217

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ORDER IN THE COURT: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE RESTORATION OF THE JAMES CITY COUNTY/WILLIAMSBURG COURTHOUSE

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Architectural Research

Williamsburg, Virginia,

1985

This research was funded in part by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities, "Planning for the Interpretation of the Courthouse of 1770" (GM-22355-85), the L.J. and Mary C. Skaggs Foundation, The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Jeffress and the Gwathmey Trusts, and the Dyson Foundation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

In the course of this research, I have received the help and advice of numerous friends and colleagues. I would like to especially recognize the work of Douglas R. Taylor, whose many courthouse drawings illustrate this report and who accompanied me in most of the fieldwork. David Konig and John Hemphill provided important information and insights into the workings of the Virginia legal system in the eighteenth century. Dr. Konig, Mark R. Wenger, and Edward Chappell have been kind enough to comment on several drafts of this report. I would also like to thank Dell Upton, who allowed me to read his book on Virginia parish churches before it was published.

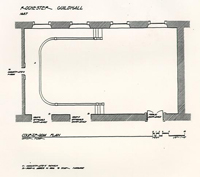

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse, c. 1876.

INTRODUCTION

The burning of colonial court books and papers stored in a warehouse in Richmond in 1865 destroyed forever any detailed history we might have had of the early public buildings in counties such as James City, New Kent and Hanover. It is ironic that the courthouses in these and other peninsular counties managed to withstand the vagaries of war only to have their records obliterated.1 Shorn of its documentary history, the James City County/Williamsburg Courthouse further suffered a disastrous fire in 1911 which left nothing but its brick walls standing, and in 1932 it underwent a vigorous restoration which destroyed much of the archaeological evidence.2 Almost nothing, therefore, is known of the construction, furnishing, and function of the building which stands on the north side of Market Square (figs. 1-3). Reconstruction of the eighteenth-century interior thus must rest upon the public records of other counties and the precedent of a few surviving buildings.

The primary source of architectural information for colonial public buildings is the county court order books. Besides being a summary of court suits, petitions, and administrative actions, these books often recorded specifications and orders for the construction and repair of

3

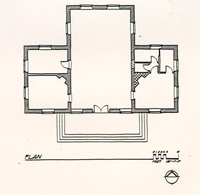

Fig. 2

Fig. 2

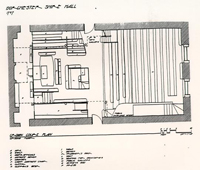

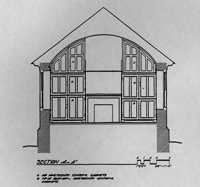

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, October, 1983. Drawn by DRT.

4

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse Interior, Late Nineteenth Century. Photo: Coleman Collection.

5

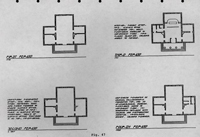

courthouses, many of which are detailed accounts of the shape, materials, and arrangement of courtroom fittings. Other references provide much useful information about the problems and procedures of selecting a county seat, the maintenance and storage of court papers and books, the undertakers and workmen involved in the fabrication and installation of furnishings, and more general information about court process and the activities of court participants. Although important information from the "burnt counties" has disappeared, a sizeable amount of material survives from dozens of others. In the course of research, the records from nearly seventy counties constituting more than a thousand court order books, ranging in date from the mid-seventeenth century though the first quarter of the nineteenth century, have been examined. Loose court papers, private manuscripts, and theVirginia Gazette have also provided a small number of useful references. The investigation of order books and other court documents turned up a handful of eighteenth-century courthouse plans. Particularly informative are the 1767 and 1791 plans for Amelia County courthouse which illustrate the arrangement of such features as the semicircular magistrates' bench, lawyers' bar, and sheriff's boxes (figs. 4, 5).

Complementary to the documentary material is the information gleaned from the field investigation of more than a hundred public buildings in Virginia, East Coast states, and England. Unfortunately, the dozen surviving

6

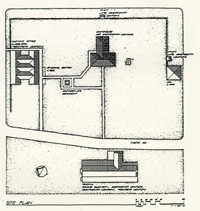

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Plan of Amelia County Courthouse, 1767. Copied from Loose Papers in Amelia County Clerk's Office.

7

Fig. 5

Fig. 5

Plan of Amelia County Courthouse, 1791. Copied from Amelia County Deed Book 1789-1791, p. 337.

8

eighteenth-century courthouses in Virginia have had their interiors altered to such an extent that very little original fabric remains. However, valuable information about the arrangement of the magistrates' bench was obtained from a close examination of the King William County courthouse. Much more useful to the study of furnishings were a score of English town halls and guildhalls which retained many early fittings, and the courthouse in Edenton, North Carolina which has preserved its original magistrates' platform, remnants of the justices' bench and panelling, and the presiding judge's chair (figs. 10, 26, 35). Eighteenth-century fittings found in several English public buildings along with surviving furnishings from Virginia's colonial parish churches are important sources of precedent that have been and should be further examined for details of the courthouse interior. Many shelves, benches, chairs, and balusters have been photographed and measured. Of course, much of the field research has been helpful in discerning the disposition and function of ancillary rooms. Material from the field has made it possible to closely analyze patterns of circulation and communication within the courtroom and between it and ancillary rooms and detached auxiliary buildings.

In eighteenth-century Virginia, court day was an experience as familiar to the lives of most free men as attending church or working in the fields. In both physical 9 eminence and practical consequence, the county court was central to the organization and ordering of colonial society. All roads wound their way past farmsteads and plantations, through forests and fields to the courthouse square and emanating from this motley collection of brick, frame and log buildings, a web of community ties and obligations spread the length and breadth of the county (fig. 6). For two, three, or four days of every month, gentlemen justices presided over the legal and administrative affairs of the county while scores of inhabitants participated in the myriad of activities which occurred inside the court and on the courthouse grounds.

The county courthouse did not stand majestically aloof from its surroundings as a symbolic monument to the power and authority of the gentry who built it and who ruled over local government, as some scholars would suggest, but was an integral part of county life. People came to the courthouse to be entertained and informed. Men and boys hung out of windows to hear the arguments of popular cases, athletes played fives against the brick walls much to the annoyance of those presiding inside, hawkers peddled spirituous beverages to hundreds of eager indulgers, merchants pinned notices on the front door calling attention to new merchandise, slave sales, and land auctions, and when court rose, itinerant ministers preached the gospel from the steps.

10

Fig. 6

Fig. 6

Hanover County: Courthouse Complex. Measured by Carl Lounsbury, November, 1983. Drawn by Douglas R. Taylor.

11

On election day freeholders filed into the courtroom to give their verbal assent and sometimes strong-arm support for their candidate. Enthusiastic voters in Essex County in 1752 demolished the lawyers' bar in an animated demonstration of electoral support.3 Those members of the community discouraged by the outcome of court proceedings had a habit of venting their frustrations and displeasure on the magistrates and the public buildings. Fearing he was about to temporarily lose his freedom for disrespectful behavior in Richmond County court, Emanuel Cleve threatened further proceedings by uttering "God dam the courte and the Justices, If they shall putt me in the stocks, I will fire the courthouse about their eares."4 Elsewhere, windows were smashed, judges' chairs defiled by excrement or a "dead and stinking hog," and entire buildings burned to the ground by those like Cleve who believed the scales of justices to be tipped in the wrong direction.5

Under the strain of continuous use and abuse, courthouses were always in need of repair. In specifying the work that was to be done, magistrates insisted that "proper" and "decent" furnishings that were "strong, workmanlike, and plain" were much preferred over those that could not withstand hard wear. Also on their mind was the limited budget that they typically had to work with. The construction and repair of public buildings was paid for out of the yearly 12 levy exacted from all tithables. Raising the levy more than what was considered needed for public works risked provoking the ire of many penurious inhabitants. The best brick courthouses complete with their fittings could be built for about half the cost of a parish church. Rarely were the words "best" or "genteel" applied to courtroom fittings.

However plain, the objects in the courtroom were not socially neutral. The chairs, benches, and tables were subtle expressions of the power and status of those who used them. To eighteenth-century society, a canopied armchair with a cushioned seat raised on a platform and a backless bench were not merely two different forms of seating; the former was viewed as a seat of honour, the latter as a seat of commonality. Placed in the same setting, the implications were that the occupant of the bench was in a subservient position and as a matter of course would defer to the occupant of the chair.

A significant transformation occurred in courtroom furnishings from the late seventeenth century to the middle of the eighteenth. Although buildings specifically erected to house county courts had appeared in Virginia by the mid-seventeenth century, these early courthouses were no more than impermanent hole-set structures barely distinguishable from neighboring farmhouses. Inside, there was little to inform the visitor of its public function. On occasion, the 13 size of the room may have been slightly larger than the halls of contemporary dwellings. Except for the bar that sometimes stretched across one end of the court, the tables, benches, and armchairs used by court officials were no different from the type of furniture found in the houses of the wealthier planters. Space within the courtroom was scarcely demarcated into areas of specialized use. The magistrates' table and benches might be arranged within the room in any number of ways. Gradually, this undifferentiated spatial appearance gave way to a courtroom where the form and arrangement of the fittings became specialized and fixed. The inside of a courtroom in 1750 could be mistaken for nothing else. It was as distinct as the inside of a church or store.

The subdivision of the courtroom into specific places and fittings for the court participants--judges, lawyers, sheriffs, clerks, the public--can be attributed to two basic causes. First, by the middle of the eighteenth century the routine and procedures of the Virginia legal system had become more regularized. There were more rules and regulations to follow in all legal matters and this affected what transpired in the courtroom. More than ever, individuals needed the help of a lawyer to successfully negotiate a case through the intricacies of the court system. As integral members of the court's routine, lawyers required a prominent place in the courtroom to follow the court's 14 actions. As the number of cases that went before a jury increased, the need arose for a permanent place for jurymen to sit in the courtroom as well. The makeshift furnishings of the earlier period would have been deemed inadequate and insufficient for the court's proper functioning.

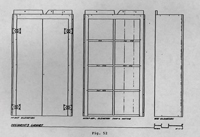

Secondly, during the same period that court routine was becoming more regularized, there was a tremendous growth of a consumer-oriented society in England and America. Economic prosperity allowed an ever-increasing number of people to purchase a wide range of consumer goods never before available. More and more goods with specialized uses appeared in an expanding market. Virginians in the first half of the eighteenth century filled their houses with new types of ceramics, textiles, and furniture. The taste for new and more specialized forms of seating furniture was carried over by county justices in equipping their courtrooms. No longer did simple backless benches suffice for magistrates' seating in the courtroom and withdrawing room. Armed chairs and panelled benches softened by cushions as well as leather-bottom side chairs took their place. Specialized furniture even appeared for the storage of papers and books. Uncompartmentalized chests gave way to specially made book presses with subdivided shelves and pigeonholes (figs. 7, 8). As much as the planters house, the appearance of the magistrate's courtroom was a product of the new consumer society.

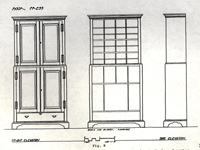

15 Fig. 7

Fig. 7

Sandwich, Kent: Guildhall, town chests.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8

Northampton County: Courthouse. Measured and drawn by Douglas R. Taylor, December, 1983.

THE MAGISTRATES' PLATFORM AND BENCH

The principal figures in the routine of court sessions were his majesty's justices of the peace, the local gentry who dominated county government in Virginia in the eighteenth century. At the far end of the courtroom opposite the entrance, the gentlemen justices sat in session upon a panelled bench raised three or four steps above the courtroom floor. To accommodate the half dozen or so attending magistrates, the long bench curved around the back wall to form a semi or quarter circle with steps at either end. Enclosing this platform on the front was a banistered railing atop which, in some cases, was fastened a shelf for books and papers. In the center of this curvilinear bench sat the first in the commission or chief magistrate who presided over the proceedings. Other members of the magistracy occupied seats on either side of him according to their rank in county society and seniority in the commission. Elevated a step above his fellow magistrates, the chief justice sat in a deep-seated armchair of imposing proportions with a canopy or pediment overhead.

The carefully devised fittings of the magistrates' bench was intended to inform court participants of the 18 hierarchical structure of the county judicial system and to identify the source of its power. This authority was expressed as the county magistrates were figuratively and literally elevated above the rest of the courtroom participants. Such seats of honour were long familiar to English custom where rigidly defined protocol dictated that the royal throne, bishop's cathedra, speaker's chair in the House of Commons, and seat of the king's justice at the county assizes be raised above all others (figs. 9, 10).6 Although relaxed and simplified by English standards, notions of status and rules of precedence also governed the placement and shape of courtroom fittings in colonial Virginia.

Centrally placed and directly above the chief magistrate's chair hung the arms of the monarch in whose name justice was carried out and to whom each justice reaffirmed his allegiance in the oaths repeated at the beginning of each new commission. Befitting the dignity of his office, the presiding justice's chair received the most elaborate ornamentation in order to distinguish it from the seats of his lesser associates. The justices of Spotsylvania County marked this distinction clearly by calling for "a handsom Chair for the Judge of ye Court with a Canopy over it" in their new courthouse in 1736.7 A rare example of this ceremonial chair survives in the 1767 courthouse in Edenton where, standing more than nine feet at the apex of its

19

Fig. 9

Fig. 9

The Speaker's Chair, House of Commons. Drawn by Sir James Thornhill. FromH. M. Colvin (ed.),The History of the King's Works, V,London,1976.

20

Fig. 10

Fig. 10

Hugh Lupus, Earl of Chester, Sitting in his Parliament. FromGeorge Omerod. History of Cheshire,London,1882. Print after a plate by Hollar.

21

pediment, it towers over the rest of the magistrates' bench (fig. 11) .

The elevated platform of the magistrates' bench was further distinguished from the rest of the courtroom by the panelled wainscotting which covered the lower part of the wall behind the seat. The plans for the 1767 courthouse in Amelia County called for "Wainscott round ye Justices seat 3 ½ foot high."8 The wainscot in the Edenton courtroom rises nearly four and a half feet above the bench and is divided into two raised panel bands of uneven size. Sometimes the area below the justices' seats, that is the lower part of the platform, was "divided wainscott fashion" as in the 1740 Lancaster County courthouse and 1791 Amelia County courthouse.9

The elevated platform and fittings with graduated ornamentation had become standard features in colonial courtrooms of Virginia by the mid-eighteenth century. Prior to this period and continuing sporadically during the next four decades in newly-settled western counties, justices were obliged to hold court in less specialized interiors. As was true of minor English courts, most seventeenth-century magistrates conducted their business around a long table on benches at the same level as the rest of the courtroom (fig. 12). Typical of Virginia courts were the fittings provided in 1685 for Rappahannock County court which consisted of a

22

Fig. 11

Fig. 11

Chowan County, North Carolina: Courthouse. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1983. Drawn by DRT.

23

Fig. 12

Fig. 12

Courtroom c. 1685. FromJohann Comenus,Orbis Sensualium Pictus,London,1685.

24

table for the justices with a "Bench of Plank sufficient to sitt upon" and "a Chaire for the President of ye Court at ye upper end of ye Table."10 York County orders in 1692 specified a ten foot long "tennant" table with two equally long forms and one three feet in length.11 In 1682 the "Seat of judicature" in the Charles County, Maryland courthouse had a six by eight foot table.12 A surviving seventeenth-century magistrates' table in the Yelde [Guild] Hall in Chippenham measures twelve by two and a half feet and separates into two pieces (fig. 13). The longest (and oldest ?) section extends more than eight feet. Other than size which varied, the tables, which justices gathered around, were no different than domestic or ecclesiastical ones (fig.14). Most probably resembled the one at Chippenham or the one in the Town Hall at Fordwich. They are joined tables with rectilinear tops and turned legs connected by plain stretchers. Undistinguished in their own right, they were often covered with cloth like communion tables.13 The justices of Surry County enhanced the dignity of their courtroom by purchasing a "carpitt for ye courthouse table" in 1678.14

Some late seventeenth-century Virginia justices chose to further emphasize the "east" or upper end of the courtroom through variations in wall, ceiling, and flooring materials and finishes. The Northumberland County courthouse was "to be lathed, filled and white limed or filled

25 Fig. 13

Fig. 13

Chippenham, Wiltshire: Yelde Hall; magistrates' table.

26 Fig. 14

Fig. 14

Table in kitchen at Shirley, Charles City, County. Photograph by Willie Graham, CWF.27

and sealed as farre as the Rayles goe at the session end of the house on both sides."15 For the rest of this 1681 structure, the framing members were to be left exposed. Floors too, were treated differently with the justices' end generally laid with plank while the public space at the lower end of the building was paved with a variety of materials. Such distinction appears in the 1704 specifications for the framed Middlesex County courthouse when the space where the "congregation" stood was to have a "good even clay floor" and the area within the bar was to be laid with grooved planks.16

The architectural demarcation between the dispensers and seekers of justice was clearly drawn. Railings had long been used in European and English society to restrict access to important places in palaces and churches. State bedchambers would often have a balustrade in front of the bed to separate the area around the bed from the rest of the room and keep all but the most favored at a distance.17 Similarly, Anglican reforms in the sixteenth century required the communion table to be surrounded by a railing in the east end of parish churches in order to provide it with a greater sense of dignity, a canon followed in seventeenth-century Virginia churches.18

The notion of restricted space was an integral part of English legal tradition as well through the employment of a "bar" to physically separate judges from the judged. Bars 28 ranged from simple movable barriers consisting of no more than a railing attached to posts such as the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century one in the Guildhall in Rochester (Figs. 15, 17, 18). Early court records in Virginia suggest that magistrates preferred a fixed balustrade of turned banisters. Such bar was to run straight across the width of the 1673 Westmoreland County courtroom at a distance of ten feet from the back wall.19 Although a powerful reminder of authority and a useful means of separating the court from the public, a bar was not always present in seventeenth-century courtrooms as the 1671 minutes of Northampton County court make clear. "For want of a Barr," a number of court sessions were disrupted by crowds of people pushing their way forward toward the seated magistrates.20

From the little evidence that survives, it appears that the fittings and finish of the justices' end of the courtroom varied widely from one county to another. In counties where no courthouse had yet been constructed, magistrates held court in dwellings, tobacco barns, or taverns and made do with whatever furniture was at hand. In wealthier or more established counties the small framed courthouse sometimes had "decent" and "convenient" seats and tables with perhaps a balustraded bar.

Even if every county had the ability and desire to build substantial courthouses, late seventeenth-century

29

Fig. 15

Fig. 15

Courtroom, Town Hall, Fordwich, Kent.P. H. Ditchfield,The Charm of the English Village,London,1908. Drawing by Sydney R. Jones.

31

Fig. 16

Fig. 16

Westminster Hall, Courts of Chancery and King's Bench in the seventeenth century, anonymous drawing in the British Museum. FromH. M. Colvin (ed.),The History of the King's Works, V,London,1976.

32

number of courtrooms were provided with fine panelled woodwork, an ornamental principal magistrate's chair surrounded by a curved bench, and a balustraded bar enclosing a raised platform. In courtrooms such as the ones in the Rochester Guildhall (1687) and Hedon Town Hall (c. 1693) the panelled and curved form of the magistrates' bench was meant to focus attention upon the entire bench, not just the chief magistrate (Figs. 17, 18, 30). It was meant to lend greater dignity to both the local squire who sat in the quarter sessions court and the wealthy merchant who sat on the borough court.

The ceremonial chair of the presiding justice retained its central position and distinctive features but it now shared its place of honour with the raised flanking built-in bench of the associate magistrates. The panelled back and occasionally the cushioned armrests marked a significant improvement over the backless benches and forms previously allotted to the junior members of the court. The enhanced status of the elevated bench curving outward from the center chair conveyed an image of corporate power and responsibility shared by an entire class of gentry officeholders. Men didn't walk into courtrooms to learn the rules of deference and the social structure of the community, since they experienced it constantly in their daily routines; what they found when they came to court was confirmation of the

33

Fig. 17

Fig. 17

Rochester, Kent: Guildhall; Magistrates' platform.

34

Fig. 18

Fig. 18

Rochester, Kent: Guildhall. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1984. Drawn by DRT.

35

hierarchy of local power.

Compared to the magistrates' bench, the rest of the courtroom was treated in a simple, if not austere manner-- plastered walls, paved floors, and little else. It was unnecessary to embellish those areas of the room such as the public space which were considered of little importance.

It was this last source of English courtroom planning which Virginians found most useful in the early eighteenth century. The seminal conduit for the spread of these English ideas was the General Court, the highest court in Virginia located in the new Capitol in Williamsburg. Looking to avoid the shabbiness and inconveniences of the old General Courthouse in Jamestown, the committee charged with devising plans for the new Capitol clearly had in mind the highly specialized arrangement of fittings found in the latest English borough and assize courts. Reviewing the progress of construction in April 1703, the committee directed:

21 36

- -That the ffootsteps of the Generall Court house be rais'd two feet from the ffloor, and the seats of benches whereon the court is to sit rais'd a convenient highth above that

- -That the circular part thereof be rais'd from the seat up to the windows

- -That there be a seat rais'd one step above the bench in the middle of the circular end of the court made chairwise

- -That the Queens Arm's be provided to set over it

Although novel for early eighteenth-century Virginia, the arrangements were straightforward in English terms. Two feet above the courtroom floor stood the magistrates' platform in the semicircular apse. The fixed "Seats or Benches" lined the apsidal wall with the seat of the chief justice (the governor) in the center. This seat was raised a step above the platform and constructed "chairwise" with arms and a tall back. Above it hung the Queen's Arms. The back of the semicircular bench was finished with raised panelling up to the lower edge of the three oeil-de-boeuf windows in the apse.

In the 1930s limited research and an unfamiliarity with early English courtrooms led the architects who designed the General Courtroom in the reconstructed Capitol to seriously misinterpret the cryptic recommendations of 1703. They unfortunately took the words "Seats or Benches" to mean individual seats or chairs rather than a fixed bench.22 The architects reasoned that chairs would have been more comfortable since General Court "sessions were often quite lengthy."23 A quick study of late seventeenth-century seating for English magistrates or even later examples from Virginia would have corrected this view. It is extremely rare to find eighteenth-century references to Virginia magistrates sitting in chairs on a raised platform.

37A second and more serious mistake was the architects' inability to decipher the instructions for "the Circular part thereof to be rais'd from the seat up to the windows." They interpreted it as being practically meaningless; what they failed to understand about this elliptic phrase was that the word "panelling" had been omitted.24 The colonial committee had intended for the courtroom to be panelled only the three and a half or four feet between the top of the bench and the lower part of the windows. Based on a 1705 specification for the "wanscote" to be painted "Like Marble," the reconstruction architects decided to construct floor to ceiling raised panelling with Ionic pilasters throughout the entire courtroom. They recognized that the term "wainscot" was applied in the eighteenth century to all heights of wooden wall panelling but felt that rooms used in the Capitol by the governor and council would have been richly decorated.25 The splendid woodwork installed in the 1930s sadly mitigates the contrast that the colonial builders had intended between an ornamented bench and a much plainer public space (Fig. 19).

The architectural influence of the capitol on public building in early eighteenth-century Virginia was profound. County courts selected elements of its plan and details in the construction of new courthouses. The bench in the 1726 Norfolk County courthouse was modelled "in the same manner as the General Courthouse."26 The plan and

38

Fig. 19

Fig. 19

The General Court in the Capitol as reconstructed by CWF, 1931-1934.

39

configuration of other county court benches varied but all conformed to the basic design established in the higher courtroom. Although raised platforms appeared in some late seventeenth-century courtrooms--the one in the Northumberland County courthouse in 1681 was "decently made with some assent"--after the completion of the General Court, almost no courtroom was planned without an elevated bench.27 A semicircular bench fixed to the back wall and fronted by a curved balustrade replaced the old haphazard arrangement of assorted benches and chairs spread around a large movable justices' table. Typical of new construction was the 1736 Spotsylvania County courthouse with its wainscotted justices bench raised "a proper height" above the courtroom floor with "a handsome chair for the judge of the court with a canopy over it."28 By mid-century this design had become so standardized that specifications for new construction rarely went into as much detail as the Spotsylvania example but merely noted that the magistrates' bench should be built "in the usual manner."

These fixed courtroom arrangements with the implicit emphasis on the permanence and prestige of the magistracy were apt expressions of the growing stability of a social order dominated by a small and powerful set of gentry families. This oligarchy who controlled the bench served the county out of a sense of civic responsibility and at the same time gained an important imprimatur of status. Their 40 status was acknowledged and reaffirmed each month as they climbed the steps of the elevated bench to occupy the seats of honour.

As long as the squirearchy collectively retained jurisdiction over local affairs there were few incentives to change the form of the bench. Not until the middle of the nineteenth century when the power of the justices of the peace was being slowly curbed by democratic reforms did any noticeable change occur in the arrangement or shape of the magistrates' bench. Whether from a change in the system of selecting justices or from a change in perceptions of comfort and taste, the old monolithic bench was being broken up in favor of chairs. The 1849 plans for the new Amelia County courthouse called for a space of sixteen feet be left in the center of the bench in order to fit armchairs for the four or five regular justices.29 Goochland County remodeled its bench in 1857 by removing a sizeable section in the center of the apsidal bench in order to install four armchairs.30 The 1869 Underwood Constitution abolished the system of multiple magistrates in lower courts in favour of a single justice, thus rendering the curved bench stretching across the back wall superfluous (Fig. 3).

Recommendations for the Magistrates' Platform and Bench.

1. The magistrates' platform should be elevated between two and three feet above the courtroom floor with flights of steps rising along both east and west walls of the Williamsburg Courthouse.

When the courtroom walls were partially stripped of modern plaster in 1973, traces of six steps were found on both the east and west walls (Figs. 20, 21). The heights of the platform was thus determined to be 3' 4" above the present floor level. However, the date of these stairs could not be established.31 Substantial but unspecified repairs were made to the courtroom in 1840, 1867, 1911, and 1932. The ghost marks discovered in 1973 are not necessarily those of the eighteenth-century stairs since they ascend approximately from the same level of the present courtroom floor. The colonial floor was several inches higher than the present floor level. It would be safe, therefore, to dismiss the stair ghosts as the remnants of some later pair of stairs, perhaps those of the post-Civil War repairs or even the marks of the steps installed following the 1911 fire.

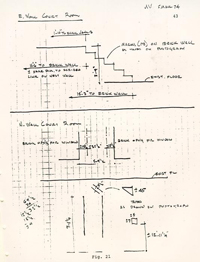

In the absence of direct structural evidence, surviving eighteenth-century platforms and documentary evidence provide the best information about platform heights. In the English courtrooms of Hedon, Blandford Forum, Malmesbury and Rochester platforms stand 1' 6", 2', 2', and 2' 4"

42

Fig. 20

Fig. 20

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse Interior, 1973.

43

Fig. 21.

Fig. 21.

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse Interior; Ghostmarks of woodwork discovered during 1973 investigations. Drawing by James F. Waite. March, 1974, CWF.

44

respectively off the courtroom floor (Figs. 22, 23, 24, 28). The 1767 platform in the Edenton Courthouse measures 2' 6" while joist pockets discovered in stripping the walls in the King William County courthouse indicate that an early nineteenth-century platform was raised about the same height. Evidence from Virginia court order books display a similar range; platforms of two feet in the 1702 Essex, 1704 Middlesex, 1726 Norfolk and 1791 Amelia courthouses; two and a half feet in the 1767 Amelia Courthouse, three feet in the 1737 Prince George County, Maryland, and 1740 Lancaster courthouses.32 Many specifications failed to give the exact dimensions for the platform, noting only that it should be "raised a proper height." There was probably no standard height during the eighteenth century, but it must have varied to accommodate individual circumstances.

With few exceptions, all platforms had stairs at each end of the bench. The center stair of the Edenton courtroom is rare. Typical was the 1726 specifications for "a pair of the stairs for the justices seat" in the Norfolk Courthouse.33 In the eighteenth century, these stairs rose along the two flanking courtroom walls as can be seen in the 1767 plan for Amelia Courthouse. By the second quarter of the nineteenth century these steps sometimes turned from the wall and curved back toward the center of the courtroom.

2. The front of the platform, should follow the curve of the bench and support a balustrade railing.

45 Fig. 22

Fig. 22

Hedon, Humberside: Town Hall. Measured by Edward Chappell, April, 1984. Drawn by DRT.

Fig. 23

Fig. 23

Rochester, Kent: Guildhall. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1984. Drawn by DRT.

Fig. 24

Fig. 24

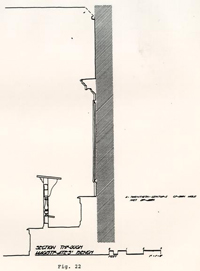

Malmesbury, Wiltshire: Courthouse, Magistrates' platform and bench.

Surviving eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century plans show the correlation between the curve of the platform and the configuration of the bench. The depth of the platform varied to meet two criteria. It had to be deep enough to allow passage for judges to and from their places on the bench but narrow enough to allow them to easily reach their papers, which sometimes rested on a ledge atop the railing.

Documents always describe the bar in front of the bench as a balustrade. As evident in the 1767 and 1791 Amelia plans, it extended from the foot of the steps along the edge of the platform (Figs. 4, 5). To ensure the seated magistrates an unobstructed view of the courtroom, balustrade heights varied between two and a half and three feet.

Railing shelves used to hold papers and books appear in some English courtrooms, notably Hedon, Malmesbury and Richmond (Figs. 22, 24, 25). Occasionally, these shelves or desks were confined to the space in front of the presiding magistrate, presumably because he was involved in most of the paper work of the bench. Whether such shelves were a part of the magistrates' bench in colonial Virginia is uncertain. An 1806 order for Richmond County court mentions a "new strong blue or green cloth to be provided for the top railing" which suggests the possibility of the balustrade supporting a shelf covered with baize as seen in some English Courts.34 A more oblique reference a few years later to the "cloth and

49 Fig. 25

Fig. 25

Malmesbury, Wiltshire: Courthouse. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1984. Drawn by DRT.50

lining of the banisters on front of the bench" in neighboring Lancaster County court again might connote the presence of a shelf. In 1816 Southampton County magistrates wanted alterations "made to the front of the banisters so as to make the same more convenient to write upon," but this order may refer to the lawyers' bar rather than the bench.35

3. There should be a curvilinear bench for the justices with a pedimented armchair for the presiding magistrate.

The most common, if not universal, seating arrangement for county magistrates in the last two-thirds of the eighteenth century was a curved bench. In the 1726 Norfolk, 1740 Lancaster, 1750 Richmond, 1752 Prince William, 1758 Loudoun, 1767 Edenton and 1791 Amelia courthouses, the bench formed a semicircle (Figs. 5, 26, 27). There were variants of the dominant form, among them one with a flattened arc in the middle of the semicircle. With the back part of the bench running parallel with the back wall, an elongated semicircle was planned for the 1767 Amelia Courthouse, and a very similar arrangement appears in the 1734 Town Hall in Blandford Forum, Dorset (Figs. 4, 28, 29). By flattening out the curve, less dead space was produced in the corners by the side and back walls. The quarter circles specified for the 1766 Bedford and 1779 Rockbridge courthouses also reduced the amount of dead corner space (Fig. 45). In the late seventeenth-century Hedon Town Hall and in Thomas

51

RICHMOND COUNTY COURTHOUSE

RICHMOND COUNTY COURTHOUSE

Fig. 26

Richmond County: Courthouse. Plan based on drawings by T. Buckler Ghequiere, published inThe American Architect and Building News,June 23, 1877. Additional measurements by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1983. Drawn by DRT.

52

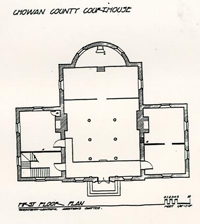

CHOWAN COUNTY COURTHOUSE

CHOWAN COUNTY COURTHOUSE

Fig. 27

Chowan County, North Carolina: Courthouse. Measured by Carl Lounsbury, Susan Lounsbury, and Douglas R. Taylor, September, 1983. Drawn by DRT.

53

Fig. 28

Fig. 28

Blandford Forum, Dorset: Town Hall; Magistrates' platform.

54

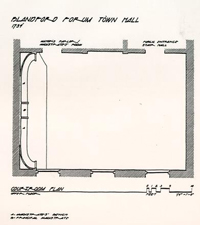

BLANDFORD FORUM TOWN HALL

BLANDFORD FORUM TOWN HALL

Fig. 29

Blandford Forum, Dorset: Town Hall. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1984. Drawn by DRT.

55

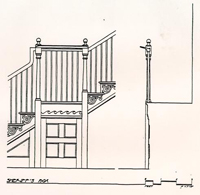

Jefferson's 1821 plan for the Buckingham County courthouse, the bench stretched around the back of the room in three segments of a polygon (Figs. 30, 31). In this latter plan, the presiding magistrate's chair was designed to stand separately from the bench. In all other plans and in the English examples, the chair was connected to the bench.

There is no indication that Virginia magistrates sat in any type of furniture other than a long curvilinear bench with a back. Chairs can be found in use in some late seventeenth-century Virginia courtrooms, but by the second quarter of the eighteenth century they had been replaced by the built-in bench. References appear in court order books after 1725 concerning the purchase of chairs for the use of the court but these were intended for seating in the ancillary magistrates' room. The dozen "leather chairs" purchased by Spotsylvania justices in 1746 were certainly used in this way since the courtroom had a magistrates' bench.36 For slightly different purposes the justices of Westmoreland County purchased "twelve good Flag chairs and a large strong table to hold a dozen people to dine at for the room adjoining the courthouse."37

All chairs except one disappeared from the bench. The chair of the presiding magistrate stood a step or two above the platform. This relationship is evident in the surviving chair in Edenton as well as in numerous English

56

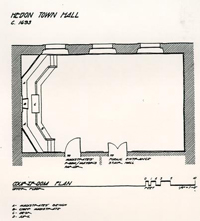

HEDON TOWN HALL c. 1693

HEDON TOWN HALL c. 1693

Fig. 30

Hedon, Humberside: Town Hall. Measured by Edward Chappell, Carl Lounsbury, and Douglas R. Taylor, April, 1984. Drawn by DRT.

57

Fig. 31

Fig. 31

Plan for Buckingham County Courthouse, 1821. Thomas Jefferson delin. FromFiske Kimball,Thomas Jefferson Architect, Boston,1916, reprint,New York:DeCapo Press,1968.

58

examples. The 1703 General Court specification and several later county references indicate that such practice was common. Less is known about the appearance of these chairs. Most probably had arms with a tall panelled or plain wooden back and capped by a pediment or canopy. The depth of the seat was probably deeper than any other in the courtroom; the depth of the one in Edenton is nearly two inches deeper than the associates' bench. Surviving chairs at Blandford Forum, Edenton, and the Speaker's chair in the House of Burgesses were probably typical of the style and degree of ornamentation of the many that were constructed in Virginia courtrooms (Figs. 11, 28, 32, 33). Evidence for a chair was fortuitously discovered during the 1973 investigation of the Williamsburg courthouse. Centered between the two back (north) windows were ghost marks of the back edge of the eighteenth-century presiding justices' chair. Approximately three feet in width, the marks appear a few inches above the level of the windowsill and run vertically up the wall to a point just over nine feet from the present floor level. Just above these two parallel lines, marks were discovered revealing the position of the pediment (Fig. 21).38

4. The relationship of the back of the bench to the back wall is ambiguous. Several eighteenth-century precedents for tying a curvilinear bench to rectilinear walls should be examined in light of the constraints imposed by the position

59

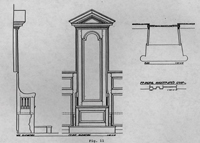

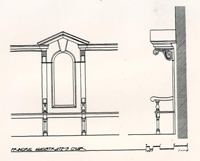

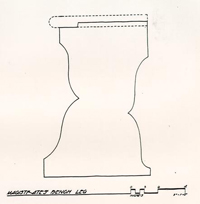

PRINCIPAL MAGISTRATE'S CHAIR

PRINCIPAL MAGISTRATE'S CHAIR

Fig. 32

Blandford Forum, Dorset: Town Hall. Measured and drawn by Douglas R. Taylor, March, 1984.

60

Fig. 33

Fig. 33

Speaker's Chair, Virginia House of Burgesses.

61

of the back windows in the Williamsburg courthouse.

Unfortunately, the two Amelia plans as well as the 1779 Rockbridge one provide few clues about handling this problem (Figs. 4, 5, 45). How was the dead space in the corners treated? Was it panelled up to a certain height and then boarded over at the top as was done in the English courtrooms at Hedon and Blandford Forum (Fig. 28)? In several rectilinear courtrooms (as opposed to apsidal ones where no problem of dead space existed) such as Spotsylvania (1736), Amelia (1767), and Surry (1795), the back of the bench was wainscoted three to four feet above the bench. How was this paneling applied--to the back and side walls free of the bench or were the corners paneled and plastered up to the ceiling?

Questions also arise about the relationship of the two back windows to the bench and back paneling. The windowsills are going to be near the floor level of the magistrates' platform. A bench that connects to the presiding justice's chair will block the lower part of the windows. Such an arrangement can be found in the galleries of several Virginia churches. If the bench has a paneled back, then that much more of the window will be blocked. If it curves sharply from the center to form a semicircle, there will be deep window reveals.

5. There should be individual cushions for the bench and chair. In the eighteenth-century cushions connoted luxury and ease and still bore intimations of status and dignity. They were requisite fittings for all ceremonial chairs. The General Court had thirteen green cloth cushions by 1722, if not earlier. A 1703 order called for all the seats in the General Court to be covered with "Green Serge and Stuft with hair."39 Cushions also provided some measure of relief from the long hours on the bench as the magistrates of Richmond County understood when they ordered "one for the chair, six on each side…for the convenience of doing business."40

6. The king's arms should be hung directly above the presiding magistrate's chair.

The significance of the royal coat of arms and its position in the courtroom has already been pointed out. A painting of the king's arms appeared in the statehouse in Jamestown in 1684.41 The earliest reference to this symbol of authority in county courts is in the courthouse built by Robert "King" Carter for Lancaster in 1699.42 The 1703 specification for the General Court instructed the arms of Queen Anne to be set above the chair of the principal magistrate (the governor). This precedent was followed in the lower courts; Westmoreland court had the Queen's arms "fixed in a large handsome frame…sett upp over the 63 the Justices seat."43 Investigation of the Williamsburg courthouse revealed a nailing block in the center of the back wall almost thirteen feet above the present floor and directly above the pediment of the chair to which the royal arms would have been attached (Fig. 21).

The question arises as to the medium employed for depicting the coat of arms. In England dozens of royal arms painted on wood and canvas, carved in wood, and moulded in plaster survive in town halls and market houses (Figs. 17, 34, 35). They range in date from Charles I to Victoria. In Virginia, framed paintings (whether on wood or canvas is uncertain) must have been the most prevalent medium. In the late 1730s painter Charles Bridges executed a number of paintings of the king's arms for county courts.44 Examples of carved arms have not been found, but this does not preclude the possibility that such carvings existed in the county courts, particularly in Williamsburg where there would have been some skilled woodworkers capable of such work. George Cooke's 1820s painting of the Hanover Courthouse interior depicts a carved coat of arms above the justices' bench and suggests that such carved work may have been in existence in the eighteenth century.

7. The fittings of the judges' platform should have the most elaborate finished in the courtroom.

64 Fig. 34

Fig. 34

Dorchester, Dorset: Shire Hall; Carved coat of arms and canopy above the presiding justice's chair. Clerk's table in foreground.

Fig. 35

Fig. 35

Amersham, Buckinghamshire: Town Hall; Charles II coat of arms on canvas.

From small details to larger forms, the architectural treatment of the magistrates' platform should be indicative of the high status of its occupants. No other area of the courtroom, with the exception of the sheriff's box, should rival the platform in its richness of ornament and detail. Rarely did eighteenth-century specifications call for wainscoting except around the platform. In English and Virginia courtrooms, the seat of the magistrates' bench was invariably the deepest. Goochland justices in 1826 called for their bench to be two inches deeper than those built for the jury and lawyers.45 In several English courtrooms such minor details on railings and door architraves were much more elaborate around the justices' bench than anywhere else. This hierarchical treatment of fittings should be kept in mind when designing the courtroom arrangements.

THE JURY BENCH

Directly below the bench of the gentlemen justices was a narrower empanelled bench of the same curvilinear form reserved for the occasional sitting of petit juries. Legal authority may have emanated from the magistrates' bench; however, the close proximity of this less ornate but similar seating arrangement indicated that the jury system provided freeholders of the county with an important instrument for exercising some power in local affairs. Although found in a few English courtrooms, the placement of a jury bench in such a position varied from standard practice in England and other American colonies. In most eighteenth-century courtrooms, the petit jury was accommodated in a "box" which consisted of two or three rows of benches enclosed by panels or a balustrade. Jury boxes stood to one side of the justices' bench with the jurymen seated at right angles to the justices and the rest of the courtroom. In Virginia, the appearance of a long jury bench that faced the courtroom closely followed the development of the curvilinear justices' bench in the early eighteenth century.

Until the very late seventeenth century, there was no place specifically set aside for petit juries in 68 Virginia courtrooms. This can be explained in part by the fact that jury trials occurred so rarely. From 1681 to 1686 only two cases went before a jury in Lancaster County while in the older and more populous county of York there were only thirteen trials heard by a jury over a similar five-year period.46 Months passed in many counties between jury trials. When a jury was summoned to hear a case, they gathered in the courtroom and stood close by the magistrates' table to hear the arguments of a case. By 1691 Westmoreland had provided a railing for the jury to stand behind during a trial.47 Other counties such as Essex in 1702 and Middlesex in 1704 followed suit by building an enclosed "place for the jury."48 Although information is scanty, probably by the first quarter of the eighteenth century, most courtrooms had some sort of "suitable rails and balusters round where the petit jurys must stand."49

In 1709 and 1710 the first references to a jury sitting in a courtroom appear. Middlesex judges ordered a bench to be set up for the jury in front of the justices' seat, while Lancaster magistrates purchased two forms (backless benches) for the jury.50 No doubt this marked a significant relief for jurors who previously stood through long involved cases, but more importantly, it confirmed the notion that the petit jury was an integral part of the judicial system. Courtroom etiquette dictated that subservient 69 persons stand in the presence of those of higher status. During court sessions the public stood at the back of the courtroom. Lawyers seated at the bar rose to address the seated members of the bench. Once jurymen were provided with seats, they were in effect, treated in the same deferential manner accorded the magistrates.

Freestanding benches or forms were used in many Virginia courtrooms through the end of the colonial period but more and more courts chose, as did the Lancaster Court in 1740, to build a curved and fixed "seat for the jury under the justices."51 All surviving eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century plans show this arrangement which must have become standard by the time of the Revolution.

Recommendations for the Jury Bench.

1. There should be a built-in jury bench located below the justices' bench and it should follow the same curvilinear shape of the platform.

Although there are few specifications for jury benches in eighteenth-century court orders, the 1767 and 1791 Amelia plans as well as the 1779 Rockbridge and 1821 Buckingham plans show it following the outline of the magistrates' bench (Figs. 4, 5, 31, 45). The late 1820s painting depicting Patrick Henry speaking before the justices in the 70 Hanover Courthouse shows the jurors sitting on a plain bench in front of the magistrates' platform (Fig. 39).

2. Like the magistrates' bench, the narrower jury bench should be supported on a series of double ogee-faced legs.

The magistrates' benches in the Edenton Courthouse and in the Richmond (North Yorkshire) Town Hall have surviving double ogee-faced bench legs (Figs. 36, 37). In colonial Virginia churches such as Christ Church, Lancaster and St. Mary's White Chapel, pews are supported by similar type legs.

71 Fig. 36

Fig. 36

Chowan County, North Carolina: Courthouse Interior; Detail of presiding justice's chair and bench leg of associate magistrates' bench.

Fig. 37

Fig. 37

MAGISTRATES' BENCH LEG

Richmond, North Yorkshire: Town Hall. Measured by Carl Lounsbury, April, 1984. Drawn by Douglas R. Taylor.

THE CLERK'S TABLE

Just in front of the jury bench and facing the courtroom stood the table and chair of the county clerk, a man trained and appointed by the provincial secretary in Williamsburg. The clerk's principal responsibilities during court sessions were to help schedule the business of the court, keep track of the papers connected with each case, and take minutes of the court's proceedings. The central location of the clerk within the curved space created by the justices' platform allowed him to be cognizant of the proceedings from the bench, sheriff's box and lawyers' bar.

From the formation of the first county courts, clerks were an integral part of the judicial process but strangely, it is not until 1696 that any mention is made in county order books about accommodating the clerk in the courtroom. Presumably, through most of the seventeenth century the clerk sat at a small table near the justices' table or sat at the same table as the magistrates. After the Essex County magistrates ordered a table and chair for their clerk in 1696, Warwick and Middlesex courts soon followed suit.52 Unfortunately, most eighteenth-century references to the clerk's table fail to be very specific about its size or 74 fittings. It is clear from a 1735 order for Prince George's County, Maryland, the 1821 Jefferson plan for Buckingham Courthouse, and the illustration of the Hanover courtroom that the clerk was centered directly below the justices and in front of the jury bench (Figs. 31, 39).53 This position corresponds to numerous eighteenth-century English plans as well (Figs. 34, 40, 41). It can also be established that from the 1750s onward a large percentage of Virginia tables were enclosed on the front, sides and occasionally the back by a balustraded railing. In the 1773 reference to the Goochland clerk's table, the banisters were to stand six inches above the surface of the table.54 This railing, as well as others, may have in fact been attached only to the surface of the table and not reached all the way down to the floor.

What remains uncertain is the size of the desk. Clerks in English courtrooms shared a large desk with counsel and other court officials. The table in the crown courtroom in the Dorchester Shire Hall measures five by ten feet with benches on three sides for court participants and a chair for the clerk on the side fronting the justices' bench (Fig. 34, 40). In Virginia there was a clear separation between clerks and lawyers. Clerks sat alone, or at least with their deputies, at a table that stood several feet away from the benches provided for lawyers and litigants.

75 Fig. 38

Fig. 38

Clerk at the Earl of Chester's Parliament. Print after Hollar. FromGeorge Omerod. History of Cheshire,London,1882.

Fig. 39

Fig. 39

Clerk, Hanover Courthouse. Detail of a painting by George Cooke, c. 1825. Virginia Historical Society.

DORCHESTER SHIRE HALL

DORCHESTER SHIRE HALL

Fig. 40

Dorchester, Dorset: Shire Hall. Measured by Carl Lounsbury and Douglas R. Taylor, March,1984. Drawn by DRT.

Recommendations for the Clerk's Table.

There should be a table and side chair for the clerk at a convenient distance in front of the jury bench.

From the evidence presented above, the position of the clerk should be just forward of the jury bench. The size of the table remains an open question. It should range from two and a half to four feet in width and from five to six and a half feet in length. To a certain extent the size of the table will be dictated by the space available. It should have a drawer with lock on it for the storage of papers. Several eighteenth-century court orders specified such a feature so that the clerk could secure his papers during the recess of court sessions. The number of references to banistered tables suggests that the practice was fairly widespread. With railing on three sides, this would mean that the position of the table would be fixed and not moveable (Fig. 41). An alternative would be to have a short balustrade of a few inches in height atop the table.

Clerks sat in chairs; however, there are no descriptions of the type or quality of chair provided him. Presumably, it would have been a relatively plain side chair.

79 Fig. 41

Fig. 41

"Paul before Felix," by William Hogarth. FromRonald Paulson (ed.),Hogarth's Graphic Works,New Haven,1965.

THE SHERIFF'S BOX

At the foot of the steps leading to the magistrates' bench and roughly parallel to the clerk's table stood an enclosed elevated platform. The position of the sheriff's box was devised to allow the court's chief executive officer to effectively perform his various courtroom duties. The proximity of the box to the bench and clerk enabled the sheriff to inform and follow the court's proceedings as well as pass papers back and forth to other officials. Its location along the side wall near the gate of the lawyer's bar made it possible for the sheriff to prohibit unauthorized persons from entering into the area within the bar. Advantageously perched on his platform, he could monitor the behavior of the public and deal with those who disrupted the orderly decorum of the courtroom.

The office of sheriff rotated among the justices of the peace; the most senior member of the commission was appointed to this lucrative office for a year or two before it descended to the next ranking magistrate. The paneled box raised three or four steps above the courtroom floor underscored the fact that the status of the sheriff was equal to that of his former colleagues on the bench.

81As is true of other courtroom features, early court records are mute about fittings for the sheriff and his subordinates. The sheriff appeared at each court session (the function of court business would have been nearly impossible without him), and it seems likely that he took a seat at the magistrates' table or sat on a bench nearby. Presumably, undersheriffs, constables, and cryers remained standing around the periphery of the courtroom when they were not engaged in their duties. The earliest reference to accommodations for a sheriff sheds little light on the nature of the seating or its location. In 1704 the Middlesex County court directed that its new courtroom be made with a "convenient place for the sheriff."56 Not until thirty years later do the next references appear in Virginia court books, and these only cryptically mention benches for the sheriff and his deputies and provide no information about their placement.57

By the 1740s a significant change had taken place, one that must have started some years before. Elevated built-in boxes had been constructed at the end of the justices' platform for the sheriff and undersheriff or cryer. Such an arrangement is first mentioned in a 1744 Spotsylvania record, but the order noted that it was "Usuall in Courthouses" which implies a widespread acceptance by that time.58 Certainly after mid-century, the sheriff's box had become

82

SHERIFF'S BOX

SHERIFF'S BOX

Fig. 42

Fluvanna County: Courthouse. Measured and drawn by Douglas R. Taylor, November, 1983.

83

a standard fitting for no other furnishings appear in Virginia records through the middle of the nineteenth century.

Recommendations for the Sheriff's Box.

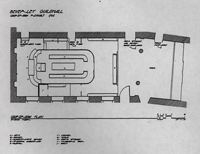

1. There should be two sheriff's boxes located at the foot of the steps leading to the magistrates' bench.

Some courtrooms had only one box for the sheriff, but most had another at the opposite end of the magistrates' platform which was used by the undersheriff or court cryer to announce each case as it came before the court. Excavation of the 1762 Prince William County courthouse revealed that a nine by six foot space was provided at the juncture of the apsidal justices' platform and the courtroom for two sheriff boxes (Fig. 43). They are also shown in this same position in the 1779 Rockbridge County plan, the 1791 Amelia County plan, and three of the 1809 Nelson County plans (Figs. 5, 44, 45).

2. The sheriff's boxes should be elevated three or four steps above the courtroom floor.

Befitting his station, the sheriff sat at the same height as his former colleagues on the bench. The 1791 Amelia plan shows the two boxes raised three steps, the same number as the magistrates' platform. An 1849 specification for yet another Amelia Courthouse required the box to be

84

PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY COURTHOUSE

PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY COURTHOUSE

Fig. 43

Dumfries, Prince William County: 1762 courthouse plan. Position of the sheriff's boxes marked A.

85

1809 DRAFT PROPOSALS FOR NELSON COUNTY COURTHOUSE

1809 DRAFT PROPOSALS FOR NELSON COUNTY COURTHOUSE

Fig. 44

Nelson County: Courthouse Proposals. Drawn from plans in the Massie Family Papers, Virginia Historical Society by Douglas R. Taylor.

86

two feet.59

3. The sheriff's boxes should be enclosed by panelling with a shelf and seat.

In many respects similar to a simplified pulpit, the sheriff's box was a small cubicle, perhaps three by four feet in dimension, ornamented with raised paneling. Because the sheriff dealt with many court papers, his box had a tilted shelf for their accommodation. The sheriff sat either on a built-in bench or, if space was sufficient, in a side chair. The only illustration of a box appears in the late 1820s painting depicting the Hanover courtroom in the mid-eighteenth century. The similarity of this box with the reading desk in the pulpits at Christ Church in Lancaster County and Aquia Church in Stafford County suggests that an ecclesiastical form may have been the source for this courtroom fitting. Since churches and courthouses were often built and repaired by the same undertakers and workmen, surviving church furnishings should prove to be useful in the design details for much of the courtroom furniture.

THE LAWYERS' BAR

Stretching across the center of the courtroom and separating public space from the area reserved for court officials, the lawyers' bar provided seating for attorneys and perhaps litigants and witnesses. Consisting of one or two long rows of benches enclosed by a balustrade, it stood in the noisy courtroom within easy earshot of the magistrates' platform. Small ledges or shelves were built in front of the narrow benches to give the lawyers a place to write or hold their papers. Whether the bar was subdivided or arranged with specific seats for plaintiffs, defendants, lawyers, and the king's attorney is uncertain, but it must have been a very crowded space during busy sessions. A late eighteenth century attorney complained to the justices of Lunenburg County about the cramped accommodations that he and his colleagues suffered in their court. While magistrates "loll upon the bench," lawyers were:

Confin'd within a compass three yards long, We scarce can stand admist the brawling throng, Wedg'd in by shoulders, outstretch'd arms and knees, Each poor Attorney scarce can fairly squeeze His carcase to a seat within the bar, Or stir his joints, so crouded is he there.60

The poem proceeds to gently mock the parsimony of the justices in a suppliant tone of sarcasm which underscores 88 the fact that through the latter half of the eighteenth century the relationship between the legal profession and county magistrates was often an adversarial one. Professional lawyers deplored the inadequacies of an untrained bench and challenged its authority. In turn, those who argued their cases on the strength of precedent and points of procedure faced independent-minded members of the bench who either ignored or treated with contempt learned arguments.61

The rise of the legal profession and the confrontations which ensued can be observed in changes in courtroom fittings. Lawyers were an integral part of the county courts through the seventeenth century but largely in the role of untrained advocates. They stood before the bar separating them from the magistrates' table to plead their client's cases. In Richmond County court and perhaps in several others, people created great confusion by crowding around the lawyers while they were at the bar.62 After each case, the lawyer stepped unceremoniously back into the undifferentiated mass of spectators. Not until 1709 do county records mention any type of accommodation for attorneys. In that year, Middlesex court ordered that a bench be set up within the bar.63 Other counties followed the Middlesex example over the next quarter century, but seating was by no means adequate, much less elegant. As late as 1723 lawyers in King George County had to make do with a simple plank seat.64

89By the middle of the century the stature of lawyers had risen. The most important change in courtroom fittings was the installation of a second bar behind their bench. The interposition of this bar between public space and the magistrates' bench acknowledged the importance of lawyers in the Virginia legal system. Whereas, in early courtrooms the public was separated from the justices by a single bar, the erection of a second one meant that face-to-face proceedings were restricted to a small few. This bar helped prevent what was now seen as the unwanted intrusion of the public in the space immediately in front of the clerk, jury, and magistrates. It confirmed the privilege of certified lawyers to pass freely into the area reserved for court officials. It also made the public more dependent than ever on lawyers. Most members of the public now faced their magistrates only through the intermediary services of a lawyer. Perhaps indicative of their growing professionalism, attorneys demanded and frequently received more elaborate benches, as well as shelves or ledges to hold their books and papers. In 1737 the bar in Essex court was constructed "with a place for them to write upon with six drawers."65

Despite improvements and the introduction of specialized fittings, there was still little doubt about the source of courtroom authority. If there was a strong confrontation between bench and bar, the fittings would suggest 90 that the magistrates still maintained control of the court. The expansive judicial platform stood well above the floorbound confinement of the lawyers' bar. The cushioned magistrates' bench itself was two or more inches deeper than the attorney seats. Cramped narrow seats did little to encourage the prolonged occupancy of the bar. Not until well into the nineteenth century did the balance of comfort become more equitable. The three-tiered bar of the 1826 Goochland courtroom stood well off the floor but not quite as high as the bench. However, it was a spacious affair, occupying more space than the magistrates' platform.66 As the power of the profession expanded at the expense of an increasingly beleaguered magistracy, lawyers began to see a substantial improvement in their accommodations in most Virginia courtrooms.

Recommendations for the Lawyer's Bar.

1. The lawyers' bar should consist of one or two rows of benches enclosed partially within a balustrade.

From the early eighteenth century onward, lawyers in Virginia sat on benches with their backs to the public facing the magistrates' bench. The 1779 Rockbridge County courthouse plan shows a long bench for the attorneys stretching across the full width of the courtroom with only a narrow space at each end separating it from the two parallel sheriff's boxes (Fig. 45). The back of the bench is

91

Fig. 45

Fig. 45

Plan of Rockbridge County Courthouse, 1779. FromRoyster Lyle,"Courthouse of Rockbridge County,"Virginia Cavalcade, XXV, (Winter,1926), p. 122.

92

balustraded. The earlier 1767 Amelia County plan doubled the space for attorneys by providing two rows of benches, each one balustraded along its back (Fig. 4). A more complex arrangement appears in the 1791 Amelia plan where the lawyers' bar consists of two rows of benches, the back one being enclosed on the side and front by a balustrade (Fig. 5). The front row is divided in half in the center, allowing access to the enclosed and undivided back bench.

Sometime in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century, the lawyers' bar began to be raised off the floor, perhaps literally, in recognition in the rising status of lawyers. If the bar consisted of two or three rows of benches, the back rows would be raised additional steps in order to give back benchers a better view of magistrates and juries. In the 1826 specifications for Goochland Courthouse, the first range of the bar was to be raised eight inches off the courtroom floor; the second range elevated eight inches above the first; and, the last range elevated eight inches above the middle one.67 The Hanover courtroom painting of the same period depicts an elevated rear bench (Fig. 46).

2. The lawyer's bar should have a ledge or shelf supported by or attached to the front balustrade.

In order to give lawyers a place to write upon as well as lay their books and papers, a small ledge should be

93

Fig. 46

Fig. 46

Patrick Henry speaking from the lawyers' bar, Hanover Courthouse. From a painting c.1825 by George Cooke, Virginia Historical Society.

94

erected atop the balustrade. From the mid-eighteenth century onward they became a standard feature.

3. Banistered gates should be placed at each end of the lawyers' bar.

In order to control access to the upper end of the courtroom, Virginia magistrates had gates built at the end of the lawyer's bar. The 1791 Amelia specifications called for "banistered Gates from the sheriffs desks to lawyers bar."68 Thus, access was restricted to two small spaces between the ends of the attorneys' bars and the two sheriff's boxes and made supervision by the sheriff and undersheriff fairly easy.

THE ANCILLARY ROOMS

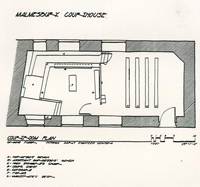

The four ancillary rooms that open off the courtroom in the Williamsburg Courthouse present a challenging problem of interpretation. Why were there so many rooms and how were they used? No other surviving or known courthouse in colonial Virginia had as many ancillary rooms; most had only one or two. Since the building on Market Square housed the Williamsburg Hustings court as well as the James City County court, there has been some speculation that the increased number of rooms was related specifically to the requirements of two separate judicatory bodies.

Ancillary rooms were generally used for three purposes in eighteenth-century Virginia: for the deliberation of juries; for private meetings of the magistrates; and for the clerk's office. However, rarely did all three groups have a separate room for their use within the same courthouse. No courthouse was without one or two jury rooms. In fact, most specifications and orders refer only to jury rooms without mentioning other specifically-named rooms. The placement of these jury rooms varied only slightly. In the simple rectangular courthouses built during the seventeenth century and occasionally in the eighteenth, a jury

96

Fig. 47

Fig. 47

James City County/Williamsburg: Courthouse. Sequential Plans. Drawn by Douglas R. Taylor, November, 1983.

97

room was sometimes constructed in a partially enclosed space in the loft. Access to the roughly finished room was by a stair usually tucked into a back corner opposite the magistrates. In the elongated rectangular plan popular throughout the eighteenth century, a partition was laid off at the opposite end of the courtroom from the magistrates' bench. As can be seen from the 1767 Amelia plan, this partitioned space was sometimes subdivided to create two small jury rooms, each roughly twelve feet square (Fig. 4). A third plan, one that appeared increasingly from the 1730s onward, had complementary jury rooms flanking the courtroom, forming a T-shaped structure (Fig. 48, 49). The advantage of the plan over the more common rectilinear plan was two-fold: first, it eliminated the need to divide part of the courtroom for jury rooms and thus provided more space for both court officials and the public and; secondly, no longer constrained by the width of the courtroom, larger jury rooms could be built. The T-shaped courthouse of King and Queen County had jury rooms fifteen by twenty-two feet and the ones at Gloucester County courthouse measure twenty by twenty-three feet. The wings of the Williamsburg Courthouse follow this pattern of enlargement (seventeen by twenty-seven feet), however, their subdivision into four rooms mitigates any sense of spaciousness.

As the name would suggest, the jury room was reserved for the meeting of juries. Grand juries which

98

Fig. 48

Fig. 48

King William County; Courthouse; T-shaped plan with jury rooms flanking the courtroom.

99

Fig. 49

Fig. 49

King William County: Courthouse. Based on Historic American Building Survey Drawings of 1936, and additional measurements by Edward Chappell, Willie Graham, Glenn Jessee, Carl Lounsbury, Douglas Taylor, and Mark R. Wenger, January, 1983. Drawn by DRT.

100

numbered up to twenty-four members sat twice a year and presumably retired to a jury room to pass on the bills of indictment brought before them. Petit juries, who sat on a bench below the magistrates, filed out of the courtroom to be closeted in a jury room for deliberations. From the early eighteenth century onward, the twelve members of the jury generally sat around a large table in the middle of the room on backless benches. Chairs could be found in only a few places.

As noted in a previous section, jury trials occurred infrequently in colonial Virginia. In the seventeenth century, many court sessions would pass between trials decided by a petit jury. Although there was a wide variation from county to county, by the end of the colonial period the number of cases heard before a jury had risen but was still only a handful, generally no more than two or three per court session. Considering that court sessions lasted from two to four days and that jury trials were sometimes heard on one particular day, then the amount of time a jury room was actually being used by juries was quite small. In the many courthouses which had more than one jury room, it is likely that some were only rarely used for their ostensible purpose. Why then did eighteenth-century Virginians go to so much trouble to build rooms that would see only limited use by juries? After all, the central element in the planning of courthouses 101 was deciding the placement of these ancillary spaces. In contrast, English town halls and market houses were rarely built with prominent jury rooms opening directly off the courtroom. What warranted their conspicuous inclusion in every single colonial courthouse built in Virginia? If infrequently occupied by juries, how then were they used?

Jury rooms must have been filled with activities which, though peripheral to the immediate action in the courtroom, were nonetheless essential for the orderly operation of court proceedings. An empty room provided a relatively private space where an attorney and his client or parties involved in litigation could confer before they were scheduled to appear in court. Minor court officials may have also periodically used the room to carry out their duties. In the many counties where no separate clerk's office had been built (James City County, for example), deputy clerks may have availed themselves of the secondary jury rooms in order to handle and keep track of the steady flow of the court's process papers that would be generated during a session. Plaintiffs, defendants, witnesses, constables, and undersheriffs sought out the clerk's deputy to file papers, check on the status of pending cases, and answer summonses.

Justices also required the services of a private room in order to set the agenda of the court's business, discuss the issues of a particularly difficult case, and 102 socialize at the court's rising. During the winter months, a small warm room, where the justices could retire to deal with many administrative matters, was much preferred over an unheated courtroom. Important county issues such as the laying of the levy or the placement and construction of new public buildings which were discussed and decided solely behind closed doors risked the censure of irate freeholders. In the late 1670s petitioners from Surry County noted that "it has been the custome of County Courts att the laying of the levy to withdraw into a private Roome by wch meanes the poore people not knowing for what they paid their levy did allways admire how their taxes could be so high." They requested that "for the future the County levy may be laid publickly in the Court house."69 Prudent magistrates were more circumspect and chose to deal with county expenditures in the open under the scrutiny of the public eye.