Wetherburn's Tavern Archaeological Report, Block 9 Building 31 Lot 20 & 21Originally entitled: "Archaeological Excavations on Colonial Lots 21 and Parts of lots 20 & 22. Wetherburn's Tavern. 1965-1966"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1173

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHAEOLOGCIAL EXCAVATIONS ON

COLONIAL LOTS 21 AND PARTS OF LOTS

20 & 22. WETHERBURN'S TAVERN.

1965-1966

CONTENTS

| Introduction | |

| Method of Excavation | 3 |

| The Tavern | 3 |

| Phase I | 4 |

| Phase II | 5 |

| Phase III | 8 |

| The Porches, Phases I, II, & III | 9 |

| The Outbuildings | 15 |

| Outbuilding A. 1. | 16 |

| A. 2. (Smokehouse) | 17 |

| A. 3. (Smokehouse) | 17 |

| A. 4. (Smokehouse/Residence) | 18 |

| B. 1. (Dairy ?) | 18 |

| B. 2. | 19 |

| C. 1. (Kitchen) | 20 |

| D. 1. (First Kitchen) | 23 |

| D. 2. (Enlarged D. 1.) | 23 |

| Buildings Flanking Wetherburn's Tavern | 25 |

| Building East A | 25 |

| East B | 28 |

| West A | 29 |

| The Wells | 31 |

| Well A | 31 |

| B | 32 |

| C | 32 |

| Walkways and Yard Metalling | 39 |

| Fencelines | 40 |

| The Fire | 41 |

| The Artifacts (Summary) | 43 |

| Conclusions | 46 |

| Appendix I:Coffee House Evidence | 48 |

| Appendix II:Archaeological Precedents Used in Landscape Reconstruction | 62 |

| Appendix III:Table of Brick Sizes and Mortar Composition | 63 |

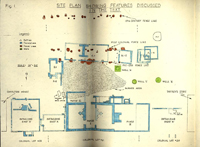

| Figure 1.Site plan showing features discussed in the text | Frontispiece |

| 2.Wetherburn's Tavern plan, Phases I, II & III | Following Page 4 |

| 3.The tavern's Phase II bulkhead sequence | Following Page 6 |

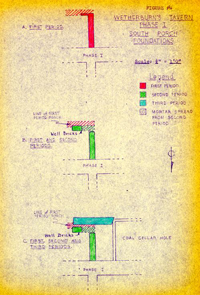

| 4.The tavern's Phase I south porch foundations | Following Page 8 |

| 5.The tavern's Phase I south porch | Following Page 10 |

| 6.Detail from the Frenchman's Map | Following Page 15 |

| 7.The foundations of the A.1-4 outbuilding complex | Following Page 17 |

| 8.The foundations of the kitchen (C.1.) and Outbuilding B. 1-2 | Following Page 21 |

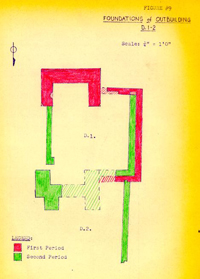

| 9.The foundations of Outbuilding D.1-2 | Following Page 24 |

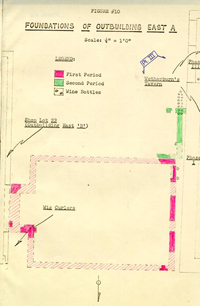

| 10.The foundations of Outbuilding East A. | Following Page 29 |

| 11.The foundations of Outbuilding West A. | Following Page 30 |

| 12.Section through Well C. | Following Page 34 |

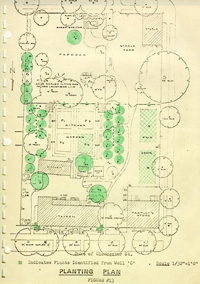

| 13.The Landscape Architect's proposed planting plan, 1967 | Following Page 61 |

| Plate I.Excavations south of Wetherburn's Tavern showing grid plan | 67 |

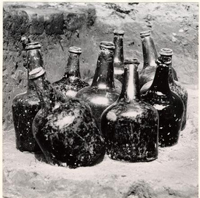

| II.Wine bottles in situ east of Outbuilding B.1. | 68 |

| III.Wine bottles in situ east of Wetherburn's Tavern | 69 |

| IV.Well B after excavation | 70 |

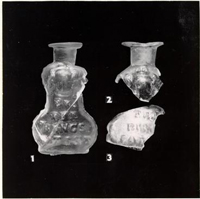

| V.A bottle for Turlington's Balsam dated 1750 | 71 |

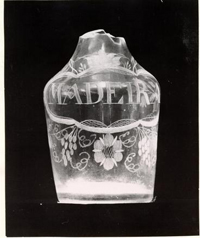

| VI.A small decanter engraved MADEIRA, c. 1755-65 | 72 |

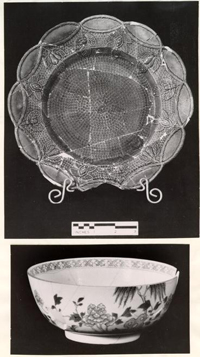

| VII.Chinese porcelain bowl and a green-glazed fruit-decorated bowl | 73 |

| VIII.The restored bucket from Well C. | 74 |

| (Plates at rear of volume) |

INTRODUCTION

The following summary of the Wetherburn Tavern archaeological excavations is intended to provide the Presentation Division with essential interpretive data. It is not intended as a substitute for a full archaeological report on the site. While a draft of that does exist, the manuscript requires substantial revision, a task that cannot be undertaken until the Research Department completes the assembling of all available documentary source material.

The archaeological information, though extensive and complex, leaves many of its own questions unanswered, and in certain respect remains at odds with both historical and architectural conclusions. However, it is hoped that much closer agreement will be reached when the new research report is available for study both by Architecture and Archaeology.

The excavations were carried out during the summers of 1965 and 1966 and resulted in the location of four seemingly contemporary outbuildings to the rear of the extant tavern (three of which have been restored or reconstructed), two other buildings between the tavern and the Charlton House and another between the tavern and Tarpley's Store. In addition, excavations around the exterior wall of the tavern exposed the remains of bulkheads and porches which were the basis for the reconstructed exterior appearance of the building.

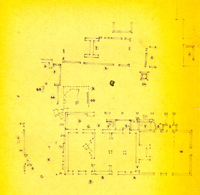

Figure 1 - Site Plan showing Features Discussed

Figure 1 - Site Plan showing Features Discussed

Besides the architectural features, something in the region of 200,000 artifacts was recovered from the site, and many of the items provided precedents for the Department of Collections' furnishing of the tavern. The artifacts also contributed to a tentative chronology for the various structural changes to the tavern and its outbuildings that occurred in the eighteenth century.

Although familiarity with the documentary evidence is necessary for a proper understanding of the archaeological reasoning, I do not propose to begin with the usual review of the Research Department's existing report.1 This omission is occasioned in part because it would make the archaeological summary unnecessarily bulky, and partly because some of Miss Stephenson's conclusions are in the process of being revised.

I propose to deal with the buildings unit by unit, beginning with the tavern itself, and because the outbuilding chronology is sometimes complex (more than one structure having occupied a single location), the sites are lettered and the structures numbered, beginning with the earliest. (See Fig. 1) Thus unit A1 refers to the first building that occupied the location of the most westerly of the reconstructed outbuildings.

7 December 1967

I.N.H.

METHOD OF EXCAVATION

The site was explored by the grid method, the lot being laid out in fifty-foot squares, each of which was subsequently divided into sixteen ten-foot squares. (Pl. 1) Balks, two and three feet in width, divided the ten-foot squares, enabling wheelbarrows of dirt to be pushed away from the site without damage to the exposed features, and at the same time preserving examples of the stratigraphy on all four sides of each square. This is the technique which has been in use in Williamsburg since 1957 (replacing the earlier cross-trenching) and is adapted from the methods used in excavating classical sites in Europe. As the work progressed, most of the balks were removed, completing the almost total excavation of the northern half of Lot 21 extending westward to Tarpley's Store on Lot 20.

THE TAVERN:

The building, as restored, evolved in three stages, a primary easterly unit, an extension to the west that almost doubled its size, and a shed addition to the southeast. These steps will hereafter be referred to as Phases I, II and III. (See Fig. 2) Numerous other changes occurred during the building's life and it remains uncertain how many of them coincided with the major expansions.

4Phase I:

Assuming that the extant superstructure is contemporary with the foundations, (Fig. 2) the extant building was originally a story and a half house measuring 45'1" x 26'2", with its first floor divided into four rooms, two on either side of a central passage, the rooms heated by corner fireplaces in triangular chimneys backing against the passage. The basement plan was rather similar, having three cellar areas divided by the rear walls of the chimneys. The date of the basement's construction has not been determined, but the thickness of the walls (2'0") is a little surprising, in that they could have supported a heavier structure. However, the same is true of the foundations of the Raleigh and King's Arms taverns. (See page 42). Unfortunately the exterior foundations had been underpinned and repaired in the mid-eighteenth century, the trenches for which had destroyed all traces of the original builders' trenches - if any had existed.

Dating for the secondary trenches is based on groups of tobacco pipe stem fragments which were recovered from those sections of the fill that were excavated. Based on the Harrington-Binford theory of stem hole dating, the groups ranged in date from

Figure 2 - Wetherburn's Tavern Plan: Phases I, II and III - oversized image

5

1738.99 to 1748.56. In an area west of the Phase I north stoop, the discovery of additional pipe fragments in a layer immediately overlying the secondary construction trench suggested a deposition date in the 1760's. Thus, it is reasonable to deduce that the underpinning and repairs occurred around 1745 or 1750 and therefore that the foundations were in existence prior to that period.

Figure 2 - Wetherburn's Tavern Plan: Phases I, II and III - oversized image

5

1738.99 to 1748.56. In an area west of the Phase I north stoop, the discovery of additional pipe fragments in a layer immediately overlying the secondary construction trench suggested a deposition date in the 1760's. Thus, it is reasonable to deduce that the underpinning and repairs occurred around 1745 or 1750 and therefore that the foundations were in existence prior to that period.

(for porch sequence see page 9.)

Phase II.

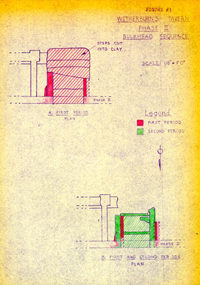

This, the westerly extension, derives most of its dating evidence from architectural data, the archaeological clues being contradictory and inconclusive. The addition measures 32'0" x 26'2" and possesses a massive chimney abutting against the Phase I west wall. (Fig. 2) At the outset, the Phase II basement measured only 24'0" x 20'0", the west end being left unexcavated. It is unclear as to whether the remaining dirt was held in place by a retaining wall or whether it was allowed to stand as a sloping bank. The fill was later dug out and the west end of the Phase II building underpinned to the same depth as the walls of the original basement. No dating evidence for this change was forthcoming from 6 within the building, but a hint is provided by the bulkhead sequence. (Fig. 3)

When first built (date uncertain) the Phase II basement was approached via a bulkhead close to its southeast corner. Only slight traces of this feature survived, but they were enough to show that it was roughly bonded into the south wall of the basement, making it likely that the bulkhead was contemporary with the construction of Phase II.2 Some time later the first bulkhead was replaced by another smaller bulkhead which was built over and in it. The date for this change is unlikely to have been before about 1770 as fragments of creamware were found in the destruction debris of the first unit. The second set of steps continued in use into the nineteenth century and was abandoned at a date after c.1820. At that time, the entrance through the wall was bricked up and converted into a basement window, while the bulkhead was plugged with yellow clay. This clay contained fragments of late transfer-printed pearlware, so providing the post 1820 terminal date. The bricks used in sealing the entrance were of similar color and size to those used in the Phase I chimneys; some of them were also soot-coated. (See Appendix III)

Figure 3 - Phase II: Bulkhead Sequence

7

On this evidence it was deduced that the bulkhead was closed at the same time that the West Phase I triangular chimney was dismantled. Thus the archaeological study of the Phase II bulkhead complex was able to contribute to our knowledge of a vanished chimney in another part of the building.

Figure 3 - Phase II: Bulkhead Sequence

7

On this evidence it was deduced that the bulkhead was closed at the same time that the West Phase I triangular chimney was dismantled. Thus the archaeological study of the Phase II bulkhead complex was able to contribute to our knowledge of a vanished chimney in another part of the building.

Architectural evidence pointed to the removal of the above-mentioned chimney around 1840, and the post 1620 terminal date for the bulkhead provided by archaeology did nothing to damage that conclusion. It can further be deduced that if c. 1840 is the true date of the bulkhead's abandonment, then that may also be the date at which the west end of the Phase II basement was dug out and underpinned: for the underpinning also contained sooted bricks at its southwest corner. At that time a new bulkhead was inserted to the west of the first two, and this opening existed until the building was restored.

In the course of the restoration works infilling within the Phase II basement fireplace was removed and behind it were found fragments of pottery and glass dating up to c.1820. However, the pieces were not seen until after they had been removed by the workmen, and it was not possible to determine how they came to be behind the brickwork.

Phase III.

The tavern building's third major eighteenth-century expansion involved the addition of a 17'5" x 10'0" shed to the southeast corner of the Phase I structure. (Fig. 2) No archaeological information was forthcoming to indicate the use to which this appendage was put, but there was evidence to indicate its construction date. Unfortunately, it did not tie in with the architectural conclusions.

The Phase III addition stands on a nine inch wall which appeared to have been constructed on the existing land surface without any builder's trench. It overlies a stratum of burned brick and clay (see page 41) which represents the residue of a fire that occurred no earlier than 1750 and probably no later than 1755. Architectural evidence demonstrated very convincingly that the Phase III shed was built against an already standing porch extending 6'1" south of the Phase I block. (Fig. 4) The corresponding foundation for that 6'1" porch was found to cut through strata containing tobacco pipe stems which, on the basis of the Harrington-Binford formula, would point to a deposition after 1761. If that is correct it follows that the shed is of a yet later date - after the demise of Henry Wetherburn.

The Porches, Phases I, II, & III.

While the principal steps in the tavern building's evolution can be fairly easily distinguished, the alterations to its entrances are far less easily correlated. Even if their various foundations survived intact, it would still be virtually impossible to be certain which stoop belonged to which combination of Phases. The difficulty has been greatly increased by the extremely mutilated condition of some of the footings and by the total absence of others.

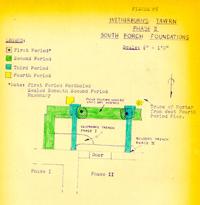

The north entrances for Phases I & II are most quickly dismissed. No foundations for either were encountered, though socket holes in the foundation of the Phase I north wall indicated the position and size of the first period entrance. (See Fig. 2) As already noted, the Phase I building possessed a north/south passage with an exit to the south, and traces of three southerly stoops or porches were located. Unfortunately, in all cases only the north-south measurements could be accurately determined, as most of the area once occupied by the porches had been dug out for the insertion of a modern bulkhead. (Fig. 4)

The first of the three south porches had a 9" foundation extending south from the tavern building for a distance of 5'3". This west side of the lost porch was 10 later overlaid by that of another extending only 4'9" from the tavern, a footing built from well bricks some 8' in length. The time span between the destruction of the first and the building of the second stoop should, in theory, have been very small. It was there fore surprising to find a 3" layer of black soil separating the two footings. The possibility exists that the first stoop belonged to an earlier building using the extant foundations.

The third stoop was more substantial than its predecessors, used a 1'1" foundation extending (as previously noted) 6'1" south from the tavern. Neither the east nor the west side of this foundation survived, that at the east having been cut by the modern bulkhead and that at the west by the insertion of a coal or root cellar following the destruction of the Phase I bulkhead. The line of the third stoop was the same as that of the eighteenth-century porch complex to the west of the cellar hole and which apparently provided entrance into the Phase II structure. (Fig. 5) For this reason Architecture decided to carry the south porch right across the reconstructed bulkhead, assuming that the southeast porch

Figure 5 - Phase II: Ssouth Porch Foundations

11

footing just described was of the same period as that of the first period porch leading into Phase II.

Figure 5 - Phase II: Ssouth Porch Foundations

11

footing just described was of the same period as that of the first period porch leading into Phase II.

The Phase II porch complex involved four different associations of foundations, the earliest being a post-supported unit measuring approximately 6'8" x 5'7". (Fig. 5) One of the post holes yielded fragments of pottery and glass of the period c.1735-45, providing a terminus post quem for the construction of the first brick foundation. This, the second entrance unit, abutted against the Phase I bulkhead, projected 6'1" from the tavern south face, and ran westward for a distance of 13'4: before being cut by the building of the Phase II first bulkhead. Thus the second porch projected from the Phase I tavern and extended westward parallel with the Phase II south wall. However, because of the loss of its west return, it is not possible to be positive that this unit was initially built as part of the Phase II expansion. The inability of either Archaeology or Architecture to provide a firm date for the construction of the Phase II building leaves the possibility that there was an earlier structure in the Phase II location, of which this entrance foundation (and also the post-supported stoop) could have been part.

12The foundation of the second porch was 1'9" in thickness including a 5 ½" exterior offset to the east, and possessed a similar offset on the inner face of the south wall. Thus the porch, if it was no more, was supported on a substantial spread footing with a brick-and-a-half wall above. It is evident that the wider foundation was considered important, otherwise it would have been omitted from the east footing where the structure abutted against the Phase I bulkhead. It has been conjectured that the setting back of the upper wall 5 ½" from the foundation was to enable the west bulkhead door to stand in the open position. It is only logical to ask: "Why so large a foundation for so light a structure?" It may be relevant to note that the substantially reconstructed steps to the two north entrances (Phases I & II) rest on one brick (9") wall, and that no traces of those foundations survived in the ground. Consequently it can be argued that the south porch must have been intended to carry a much greater load. This is acknowledged by Architecture in its decision to replace the 19" footings and the brick-and-a-half wall with a mere one brick wall, for that is patently all that is needed to support the porch as reconstructed. This decision also eliminated the 5 ½" space between 13 the bulkhead and the porch's east wall. As reconstructed, the south wall has been shortened at the west end and its 9" thickness left exposed.

Were it not for the fact that the tavern building is still standing and reveals no evidence in its superstructure of a massive appendage to the south, the archaeological evidence would be coupled with the documentary data to contend that the foundations belonged, not to an open porch, but to a porch and porch chamber - the porch chamber listed in the Dec. 19, 1760, Wetherburn inventory. This room housed a bed, two chairs, and nine chamber-pots, but it is not known whether the furnishings were merely stored there. However, if the room was actually used as a bedroom, it would have had to have been more than the 5'0" in width suggested by the foundations. In which case the room would have cut into the wall and roof line of the tavern - and no evidence of that was found. One is therefore forced back onto the unsupported theory that the Phase I foundation was not built for the present building and that another westerly extension was totally destroyed by the Phase II foundations - with the exception of the porch and porch chamber footings. All in all, this theory is based on much too much negative evidence; so one can do no 14 more than note that a very large question mark still hangs over the proper interpretation of the second porch foundation.

The second footing discussed above wrapped around an area of water-washed sand and small artifacts which seemed to have been deposited when the land surface was either unprotected by any sort of porch or by a porch that was open at either end for rain water to pass beneath it - as would have been possible during the life of the first, post-supported structure. These artifacts included 116 tobacco pipe stem fragments which provided a mean deposition date of 1740-41. It is significant that the sandy wash covered a builder's trench for the Phase I southwest corner and was cut through by the builder's trench for the Phase II basement. This is strong evidence to suggest that the first, post-supported porch belonged to an extension to the Phase I foundation predating that for the extant Phase II structure.

The third porch involved the partial dismantling of the heavy foundation at east and west, and the bonding into it of the north/south sides providing a stoop only 8'3" width. These new walls were only 9" in thickness as befitted a covered porch of that size. The new brickwork was built out into square piers at the south and west corners 15 to seat the pillars used to support the roof. Dating for this third porch is based on a single fragment of Chinese porcelain of a type one associates with the end of the eighteenth century. If this slender evidence is valid, then it is unlikely that the above described change occurred before c.1790. It is conceivable, however, that the sherd slipped into a space beside the foundation at some date later than that of the porch's construction.

A fourth stage in the porch sequence was indicated by the discovery of an L-shaped pier near the southeast corner and a spread of comparable mortar in a like position at the southwest. These remains probably date from the first half of the nineteenth century, presumably when new steps were constructed against the south face of the first period porch foundation.

THE OUTBUILDINGS

The Frenchman's map (c.1782) shows four outbuildings to the rear of the Tavern, one of them overlapping onto Lot 20. (Fig 6) Four outbuilding locations were discovered in the course of the excavations, but they did not include the unit that extended onto Lot 20. Instead, the digging revealed another structure between the kitchen and the Lot 23 property line. Not all of these buildings were erected at the same time, indeed, one outbuilding site

Figure 6 - From Frenchman's Map

16

had been occupied by four successive structures. In the interests of brevity and clarity, I propose to discuss the units in order from west to east (See Fig. 1) labeling the locations A, B, C, and D, and numbering the structures or changes to them in Arabic figures progressing from first to last. It must be remembered that this method of numbering indicates only a chronology associated with the cited location, it does not indicate any paralleling of construction or modifications on other lettered locations.

Figure 6 - From Frenchman's Map

16

had been occupied by four successive structures. In the interests of brevity and clarity, I propose to discuss the units in order from west to east (See Fig. 1) labeling the locations A, B, C, and D, and numbering the structures or changes to them in Arabic figures progressing from first to last. It must be remembered that this method of numbering indicates only a chronology associated with the cited location, it does not indicate any paralleling of construction or modifications on other lettered locations.

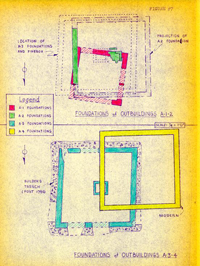

Outbuilding A.1.

A small 8'0" x 8'0" one brick foundationed structure doubtless of frame construction and perhaps used as a smokehouse. (Fig. 7) Ashes were found within it, but there was no sing of a firebox. However, the foundations and interior had been so disturbed by the building of later smokehouses on the same location that evidence of the firebox could well have been eliminated. The absence of any pit beneath the first building made it unlikely that it had been built as a privy. The building was not parallel with any of the other foundations discovered on the site, and it is possible that it was the earliest unit encountered. It has not been reconstructed.

Outbuilding A.2. (Smokehouse)

This structure was represented by nothing more than its trunkated east foundation and an incomplete firebox. (Fig.7) But going on the assumption that the box was located in the center of the building (and this was not always so) it may be deduced that the structure measured approximately 12'0" x 12'0". Artifacts found beneath the surviving wall fragment provided a construction date no earlier than 1750 and probably closer to 1760. A small number of pipe stem fragments (18) provided a mean date of 1753.56. It is this building that has been reconstructed.

Outbuilding A.3. (Smokehouse)

Another smokehouse foundation partially overlay Outbuilding A.2., and possessed comparable measurements (12'2" x 12'2") having a one brick foundation standing eight courses in height, two of them originally above the colonial grade. (Fig. 7) The firebox was virtually intact and measured 2'1" x 2'3". An informative number of artifacts was recovered from the builder's trench around this third foundation. The pottery fragments included rim sherds of both blue and green shell-edged pearlware unlikely to have been deposited before c.1790 at the earliest. This, therefore, must be considered the terminus post quem for the construction of the smokehouse. The building remained

Figure 7 - Foundations of Outbuildings

18

on this foundation until the 1920's when the then owner of the property, Mrs. Virginia Haughwout, moved the fame structure to a new location closer to the lot's west fenceline.

Figure 7 - Foundations of Outbuildings

18

on this foundation until the 1920's when the then owner of the property, Mrs. Virginia Haughwout, moved the fame structure to a new location closer to the lot's west fenceline.

Outbuilding A.4. (Smokehouse/residence)

As noted above, the building seated on the third foundation was moved in the 1920s to a new location slightly west and south of its original position. The architectural examination of this frame structure revealed that although it had clearly served as a smokehouse in the late eighteenth century (as was evidenced by the firebox), it had begun life as a dairy. The firebox had the appearance of being contemporary with the foundations, which suggested that throughout its life on the third foundation the building had been in its converted, smokehouse form. If this was so, it followed that the structure must have been moved from some other location for which it had been built as a dairy. It was therefore concluded that it had come from adjacent foundation complex here identified as Outbuilding B.

Outbuilding B.1. (Dairy)

This structure stood 5'0" to the east of foundation A.2. and 9'4" west of the kitchen (C.1.) and possessed a 19 one brick foundation measuring approximately 12'0"x 12'2". (Fig. 8) It will at once be apparent that these measurements are closely akin to those of the foundations A.2., A.3., and A.4. No evidence of fires or a firebox was found within Outbuilding B.1. and so it is reasonable to deduce that it was never used as a smokehouse. The most logical alternative would be a dairy, and for this reason the frame smokehouse from location A.4. has been restored on location B.1. - assuming that it had been moved first to A.2., then A.3, and finally to A. 4. (For dating evidence see below.)

Outbuilding B.2.

This feature is represented by a short section of a one brick foundation (rowlock course) abutting against the south interior face of the B.1. foundation and immediately inside the west foundation wall of that unit. (Fig. 8) The purpose of this inner wall is uncertain, but it is conjectured that after the dairy was removed to location A, a new and slightly smaller building was seated on the B.1. north, south, and east foundations, the rowlock course providing the new west footing. This would have created a building measuring approximately 12'0" x 11'0". The validity of this interpretation is in some doubt in view of the fact that the rowlock course is not at a right angle to the south foundation against which it abuts. While 20 it can be argued that the only complete eighteenth-century dairy/smokehouse foundation encountered (A.3.) was far from square, the interior would not have been as askew as that created by the combination of foundations B.1. and B.2. It is more reasonable to conclude therefore that B.2. was a footing for a feature within building B.1.

There is no firm dating evidence for the destruction of Outbuilding B.1., other than the fact that it predated the construction of foundation A.3. This was demonstrated by a layer of rust-stained soil that overlay the west wall of B.1. and which extended west to unit A.2., and was cut through by the foundation and builder's trench for Outbuilding A.3., i.e. circa 1790. Evidence for the construction of structure B.1. is no more precise: it rests on the evidence of a series of wine bottles buried immediately east of, and parallel to the east foundation wall. (Pl.II) The bottles had clearly been installed in the lea of structure B.1. and it therefore follows that the building was in existence prior to the date of deposition of the most recent bottle. That terminus ante quem is unlikely to have been before circa 1760 or, at best, 1755.

Outbuilding C.1. (Kitchen)

The structure measured 39'9" x 16'3", had a foundation one brick in thickness, and a large H-shaped chimney abutting 21 against the south wall close to the mid-section of the long, thin building. (Fig. 8) This division (with a linking 3'0" passage to the north of the chimney) crested two rooms on the first floor, that to the east measuring 13'9" x 12'3" and that to the west 18'0" x 14'9". The east hearth measured 8'1" x 3'1" and the west 8'3" x 3'3". There being so little to choose between the two hearth sizes, it was impossible to distinguish which room had been used for what. Both fireplaces seemed to have seen extensive service, and it is reasonable to conclude that either or both were used for general cooking. There was no evidence that either had been bricked in to provide a bake oven or a seating for laundry coppers. No evidence for the positioning of doors or windows was found, though sections of walkways were found heading in the general direction of the kitchen. However, these were of late date and stopped too far from the building to eliminate the possibility that they turned before reaching it.

Dating evidence for the destruction of the kitchen was not forthcoming as all the soil overlying the foundations had been disturbed during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. On the other hand, there is evidence for its construction, this stemming from further buried groups of bottles (See Outbuilding B.1.) deliberately interred on a straight line running east/west prior to the laying of

Figure 8 - Foundations of the Kitchen

22

the kitchen foundations. Assuming that all the bottles were buried at approximately the same time, it must be assumed that the kitchen building dates no earlier than c.1755. This conclusion is supported by the fact that a large burned area north of the kitchen and extending the southeast wing (Phase III) of the tavern also projected a short distance inside the kitchen, i.e. south of the north wall. There is irrefutable evidence that the fire could not have occurred before 1750. (See p. 41.)

Figure 8 - Foundations of the Kitchen

22

the kitchen foundations. Assuming that all the bottles were buried at approximately the same time, it must be assumed that the kitchen building dates no earlier than c.1755. This conclusion is supported by the fact that a large burned area north of the kitchen and extending the southeast wing (Phase III) of the tavern also projected a short distance inside the kitchen, i.e. south of the north wall. There is irrefutable evidence that the fire could not have occurred before 1750. (See p. 41.)

The bottle evidence not only gives a terminus post quem for the construction of the kitchen, but also shows that the dairy unit (B.1.) was in existence before that date. The bottles were buried in groups flanking the units of a series of post holes running east/west across the site. It is believed that the holes mark the line of a fence that existed when the bottles were buried - presumably in the lea of it. After the fence was removed, the north wall of the kitchen was placed on the same east/west line.

There were differences in the mortar and in the brick sizes and color, between the chimney and the wall foundations (See Appendix III) and it was conjectured that the chimney might have been built for an earlier structure. No other related evidence was forthcoming and therefore it must be supposed that the building is all of one period, 23 the differences being caused by the fact that the chimney was constructed separately, perhaps after the wall foundations had been completed. This building has been reconstructed.

Outbuilding D.1. (First kitchen?)

This small and fragmentary structure was situated a mere 1'6" from the northeast corner of the kitchen and measured approximately 12'2" by an estimated 18'3". (Fig. 9) It possessed a partial exterior chimney in the south wall with a hearth measuring 4'8" x 2'10" suggesting that the building may have resembled a smaller version of the colonial kitchen at Tutter's Neck,3 i.e. with the A-roof on the opposite axis to the chimney. The only dating evidence for this unit was provided by the fact that debris from the c.1750 fire came up to the northwest corner and did not appear inside, thus indicating that the building was in existence prior to the fire.

Outbuilding D.2. (Enlarged D.1.)

Substantial changes were made to Outbuilding D.1. at a date no earlier than about 1760, but unfortunately the 24 neither the extent nor purpose of them was revealed. (Fig. 9) An H-shaped chimney was inserted into the north wall, thus, equipping the small room of D.1., with two, facing hearths. There was no evidence that the south chimney had been pulled down when the new stack was built. An inner foundation had been constructed inside the original west and north walls (perhaps to seat the joists of a floor), while an extension had been added that projected the building at least another 10'8" to the north. Evidence for this rests on a single, one brick wall representing the west face of the addition, dating for which is provided by artifacts from a layer of ashes that passed beneath the foundation. Construction could have begun no earlier than circa 1760. A brick floor was later added to the south room (D.1.), the presence of fragments of green-edged pearl ware beneath the bricks indicating that the date of laying must have been after 1790 or even, perhaps, 1800.

So little of this building was found that no safe conclusions could be reached regarding its form, purpose, or longevity. What archaeological evidence there is suggests that it was in existence prior to 1750, that it was enlarged in the 1760s, and still standing at the end of the century. While the Frenchman's Map shows no building in the same relation to the kitchen, it does show one somewhat further to the south. The excavated building has not been reconstructed.

BUILDINGS FLANKING WETHERBURN'S TAVERN

No extant colonial buildings stood on either side of the tavern at the time it was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg, but the Frenchman's Map left no doubt that by 1782 it was hemmed in on both sides. (Fig. 6) The map proved extremely inaccurate in its rendering of the shapes and number of the units between the tavern and Tarpley's Store to the west and between the tavern and the Charlton House to the east. Archaeological evidence was more helpful. The remains of three related buildings were found and for convenience these are here designated Building East A, and East B, and Building West A, though there was no evidence of a unit B to the west.

Building East A (Tenement?)

The mutilated remains of a small building was found facing Duke of Gloucester Street virtually abutting the east wall of the tavern, there being a maximum of ten inches between the two foundations. Building East A measured 20'2" x 15'6" and seemed to have been built on piers one brick in thickness. (Fig. 10) A rowlock course extended southward on the west wall line for an additional 7'0", but the purpose of this addition is uncertain. It appears too narrow to have been a lean-to, and therefore it is more likely that it was associated either with steps or a stoop.

26The building possessed an exterior chimney to the east with a hearth measuring 4'4" x 2'0". This chimney abutted against Building East B, thus making it impossible to pass between the structures yet leaving dead space both north and south of the chimney.

The remains had been much disturbed (and in many sections, totally destroyed) by the root systems of extant trees, by planting holes, and by numerous nineteenth-century post holes along the north building line. Dating evidence was forthcoming, however, though not for the abandonment of the structure. Small deposits of domestic trash dating up to c. 1760 were found within the area of the building and it is believed that these were there before it was erected. More conclusive evidence came from beneath the southwest wall of the west pier where 31 pipe stem fragments (admittedly a small number) provided a terminus post quem having a mean date of 1765. It is also important to note that the southerly addition overlay the largest cache of once cherry-filled wine bottles. (Pl. III) Although none of these need have dated later than 1745, it is deduced that all the groups of bottles were interred at the same time, i.e. post 1755. (See page 20)

The relationship between Building East A and East B is indicated by a spread of small, hard-fired bricks of a type often described as English, which was found spreading 27 across the Lot 21-22 property line from the east. These bricks were identical to those used in the first period structure on Lot 22 (under Building East B) and other archaeological evidence suggested a construction date around 1740. The spread of bricks passed beneath the foundations of both Building East A and East B. As none of the bricks had mortar attached to them, it is concluded that they were left over after the completion of the c.1740 structure on Lot 22 and were used as a westerly yard metalling.4 If this is so, one can reasonably conclude that Lots 21 and 22 were then jointly owned. Such a contention is supported both by the Frenchman's Map (which shows no N/S division between the lots at the Duke of Gloucester Street junction ) and by the documentary evidence such as Mrs. Wetherburn's dower allotment of March 16, 1761, wherein she was left "the Dwelling House Outhouses and two Lotts of Land No. 21 & 22 in the City of Williamsburgh excepting the Tenement on Possession of James Martin Barber..." 5

It has been suggested that Building East A was, in fact, the above-mentioned tenement occupied by barber, 28 James Martin, at the time of Henry Wetherburn's death. If that is so, then the building must have been very new when Wetherburn died. However, we do know, on the evidence of the Frenchman's Map, that it existed in 1782. Furthermore, there is architectural evidence that the second floor east windows of the tavern were blocked in the eighteenth century, presumably when Building East A was constructed.

A considerable quantity of artifacts was found in the ten inch space between the tavern and Building East A. None of the items present (except two intrusive ? sherds of pearl ware) need have dated any later than c.1775, but it is uncertain how they came to be there.

The building has not been reconstructed.

Building East B (Barber's shop and office)

This structure stood on Lot 22, but because of the possible link between Lots 21 and 22, it was thought necessary to continue the Wetherburn excavations as far as the Charlton House. Building East B measured 30'0" x 26', and was divided into what are assumed to have been a shop with an office to the south. A full report on the 1966 excavations on the Charlton Site has been issued,6 and 29 therefore there is no necessity to discuss it at length. Inconclusive documentary evidence points to barber, Edward Charlton, having occupied Lot 22 from circa.1770 until 1779. His presence there could have accounted for the large number of wig curlers found in the space north of the chimney between Buildings East A and East B. (See Fig. 10) More were found to the rear of the presumed barber's shop - as well as in layers under the shop and clearly predating it. The discovery of the wig curlers was at first used as evidence to support the alleged presence of James Martin in Building East A.

Building East B was identified as an office on insurance plats dated 1796 and 1806, but it was missing from the 1823 plat, at which time it was noted as having been "pulled down". The accumulation of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century artifacts under the floor suggested that the structure had been in a poor state of repair for some years prior to its demolition.

Building West A.

This structure spanned the property boundary between Lots 20 and 21 and is shown on the Frenchman's Map as being one with the building now known as Tarpley's Store. During excavations in 1935, fragmentary foundations were found running east from the store, but they were far

Figure 10 - Foundations of Outbuilding East A

30

from informative, and the digging was not continued onto Lot 21. The section of the latter property west of Wetherburn's Tavern had been heavily used in the present century as an access route to the rear of the lot, with at least two driveway surfaces having been laid on it. In addition, most of the modern utilities followed the same line. Consequently, the eighteenth-century deposits and strata had been mutilated almost beyond recognition. Nevertheless, this area was carefully explored in 1966 and a further section of Building West A's south wall was found extending to within 3'9" of the tavern's west face. (Fig. 11) However, the corner had been destroyed and there was no way of determining the space between the two buildings - a space that the Frenchman's Map shows to have existed. (Fig. 6)

Figure 10 - Foundations of Outbuilding East A

30

from informative, and the digging was not continued onto Lot 21. The section of the latter property west of Wetherburn's Tavern had been heavily used in the present century as an access route to the rear of the lot, with at least two driveway surfaces having been laid on it. In addition, most of the modern utilities followed the same line. Consequently, the eighteenth-century deposits and strata had been mutilated almost beyond recognition. Nevertheless, this area was carefully explored in 1966 and a further section of Building West A's south wall was found extending to within 3'9" of the tavern's west face. (Fig. 11) However, the corner had been destroyed and there was no way of determining the space between the two buildings - a space that the Frenchman's Map shows to have existed. (Fig. 6)

No trace of the building's north wall was found, but it is probable that it once occupied the same line as did successive nineteenth and twentieth century fences. The holes for the fence posts created a linking chain running westward just as they did to the east of the tavern, thus destroying any foundations through which they had been cut. However, assuming that Building West A extended from the surviving south wall to the fenceline, it would have been approximately 20'7" in depth. The surviving south wall indicated that the building was at least 22'3" in east/west

Figure 11 - Foundations of Outbuilding West A

31

length.

Figure 11 - Foundations of Outbuilding West A

31

length.

No evidence of a chimney was found, but two parallel slots running north/south beyond the building line towards Duke of Gloucester Street suggest that the structure may have been entered via a stoop or steps measuring 5'9" (N/S) x 6'3" (E/W). The only other architectural information came from the 1935 excavations which yielded part of a brick tile floor extending northward from the south wall. The tiles were square and varied in size form 7" x 7" to 9" x 9". It is uncertain as to how large an area of the building they had covered.

It is assumed that the remains belonged to the building rented by Robert Bruce in 1774 and that it was subsequently used by Alexander Purdie as part of his printing office, but no archaeological dating evidence was forthcoming. The building has not been reconstructed.

THE WELLS

One well shaft was open when the property was leased by Colonial Williamsburg, and two others were found in the course of the 1966 excavations, but only one of them was ever completed. The existing shaft is hereafter identified as Well A, the unfinished hole, Well B, and the main colonial shaft, Well C. (See Fig. 1)

Well A.

This shaft was open and covered by a decaying wooden lid when 32 work began on the site. It had been in use by Mrs. Haughwout in the present century, and had almost certainly been cleaned out many times in the course of its life. Nevertheless, there was a good deal of trash in the bottom filling it up to a depth of 21'6" below modern grade. The interior diameter was very small, a mere 2'7", and the entire head foundation was only 4'6" square. It had been repaired on at least three occasions, the bricks of both lining and head foundation being of regular shape. However, shell mortar was used in the lower courses of the square foundation, indicating that it may have been built as early as the last quarter of the eighteenth century. That it could be no earlier is indicated by dating evidence retrieved from the filling of Well C. The filling at the bottom of Well A was not excavated. The shaft has not been restored.

Well B.

This well was actually located on the eastern section of colonial Lot 20 though it is evident that at the time it was dug that property line was no longer honored. (See Fig. 1) The hole was sealed by an area of nineteenth -century brick and reused-stone paving which may have been associated with the tavern's most westerly outbuilding shown on the Frenchman's Map (and later used as a school house) but for which no traces of wall foundations survived. (Fig. 6)

33An unlined hole measuring 4'9" in diameter had been sunk to a depth of 4'6" below modern grade and then abandoned. The sides were vertical and neatly trimmed, but the bottom was stepped down at the east and retained the impression of a spade blade that had been dug into it just before the work was stopped. It was evident that this hole represented the beginning of the digging of a well shaft and therefore it would have been brick-lined. However, the bricks must have been salvaged for use in another location. (Pl. IV)

The hole had been filled with yellow clay, and at the bottom, with a deposit of ashes and trash. The refuse included fragments of burned pharmaceutical bottles and, most importantly, a broken bottle of molded clear glass bearing the embossed wording "ROB TURLINGTON" BALSAM OF (LIFE) BY THE KINGS PATENT MARCH 25, 1750". (Pl. V) This provided an unequivocal terminus post quem for the filling of the hole and, presumably, for the abandonment of this particular well-digging venture.

Well C.

The unfinished Well B was located 44'6" south of the Duke of Gloucester Street building line as indicated by the north wall of the tavern. Well C occupied almost the same southerly relationship to the building line being 34 43'5" from the front of the tavern. (Fig. 1) It was dug 17'0" to the east of Well B, and it is deduced that the abandonment of the latter was occasioned by the property owner's desire to locate the shaft closer to the kitchen and the tavern's south entrance. If this is so, the archaeological dating evidence for the abandoning of Well B is also evidence for the digging of Well C.

As so often happened, Well C was robbed of its upper courses of brickwork and so, when found, resembled a deep rubbish pit. (Fig. 12) Indeed, the fill had settled from time to time and new layers of dirt had been dumped into it to fill the cavity. One of these later deposits contained a wine glass stem and a fragmentary bottle dating from the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Strata immediately beneath yielded sherds of creamware suggesting a deposition date after circa 1770. The top of the surviving intact brick courses was reached at a depth of 16'7" below modern grade, at which point the lined shaft had a somewhat elliptical shape measuring 3'0" x 3'3". At a depth of approximately 18'8" were found two clear glass medicine phials (one with its contents intact) and the boy of a miniature decanter engraved MADEIRA. The engraving was typical of a style known as a "lable" decanter which became popular in London around 1755. (Pl. VI)

Figure 12 - Wetherburn Tavern: Colonial Well- oversized image

Figure 12 - Wetherburn Tavern: Colonial Well- oversized image

At a depth of 19'7" below modern grade the bricks used in lining the shaft changed size, those above measuring 7 ½" x 4 ¾" x 3 ½" x 2 ½" and those below 8 ¼" x 4 ¼" x 3 ¼" x 2 ½". It was not certain whether this change was evidence of a rebuilding of the well's upper courses or whether the builder simply ran out of bricks before the job was finished. The correct interpretation is important because the lower bricks are of the same measurements as those used in the second stoop foundation for the south door in the Phase I tavern structure (See page 9 and Fig. 4). If, as the Well B evidence suggests, Well C was not built prior to 1750, it might reasonably be argued that the second Phase I stoop was built at the same time. However, if Well C is of one period of construction, the larger bricks must have been expended before the well was completed - making it unlikely that any would have been left over for other jobs. Alternatively, of course, one might contend that the small number of bricks needed for the stoop was taken prior to or during the construction of the well before the supply ran out.

Here again, as in the case of the abandonment of the Phase II bulkhead which yielded evidence of the dismantling of a chimney elsewhere in the building, (page 6) we have an example of the way in which archaeological data found in one location may have an important bearing on the 36 interpretation of features in another.

The shaft was filled with dirty clay and brickbats from a depth of approximately 19'0" below modern grade downwards. At 24'4" below modern grade the bricks became more concentrated and consisted entirely of the shorter type used in the well's lining above the 19'7" mark; then at 31'6" these gave way to ordinary rectangular bricks (8 ¼" x 3 7/8" x 2 ¾") some of which had scraps of mortar adhering to them. It is thought that the latter bricks came from the dismantling of the square well head, an operation that would have preceded the removal of the upper courses of lining and which would, therefore, have resulted in broken and fugitive bricks falling into the lower levels of the shaft.

The brick lining stopped at 39'3" below modern grade, resting on the usual wooden ring on which the courses were seated during installation. The ring was 3" in thickness and had an internal diameter of 2'1", and it served to hold the bottom course of bricks in position when the ground beneath was eroded by water action or by the cleaning of the well bottom. In theory the securing of the bottom course held all the others firmly in position, but in practice it did not always do so. In the case of Well C, a hole had developed in the lining at a depth of 36'0" below modern grade, and water and mud were pouring continuously through 37 it as the excavation went on. The danger of the entire lining collapsing was such that the shaft was not cleaned out in its entirety below the wooden ring. However, groping through the brick rubble it was possible to extract an intact wine bottle of c. 1745-60, some scraps of brass waste and pieces of turned lead used in casement windows. Scattered through the lower levels of the filling were fragments of an elaborately molded, fruit-ornamented plate coated with the green glaze that Wedgwood described in his experiment book of 1759. It is unlikely that such a plate would have found its way into the Wetherburn well much before 1765. (Pl. VII)

Among the artifacts from the lower levels was the blade and broken wooden handle from an adze. It was assumed that this find was simply one more piece of trash thrown into the well after its abandonment. But it is now considered possible that this was the tool used to pry the bricks loose as the walls were dismantled. That conclusion is based on the discovery of a similar adze (this time with its handle intact) in a colonial well shaft at the James Geddy House site, a shaft whose entire lining had been salvaged. The adze and a wooden-handled spade were the only artifacts recovered from the lower filling of the Geddy well and it is deduced that both were left behind at the conclusion of the salvage operation.

The most significant single item from the Wetherburn 38 Well C was the oak bucket used to haul water. (Pl. VIII) This was found at a depth of 32'8". It was a much larger bucket than had been found in any previously excavated Williamsburg well, 1'1 ¾" in height with a top diameter of 1'2". When full, allowing for loss during the ascent, it would have held approximately six gallons of 48 lbs. The bucket with its iron handle attached weighs 12 ¾ lbs. It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that when the filled bucket broke the surface of the water the load was close to 65 lbs. The weight was further increased by the fact that the bucket was attached to an iron chain and not to a rope. The chain was permanently anchored to the handle by means of a swivel eye and two links were rusted to it. A mass of chain of the same size links (plus sections with smaller links) was also found in the fill close to the bucket. Although it was not possible to unravel the corroded chain, it is known to have been at least five feet long with another swivel in its mid section. Both swivels were intended to enable the bucket to spin on its way up without tangling the chain. The rig had presumably seen a great deal of use, for some of the chain links had almost worn through and had been reinforce with thongs. There can be little doubt that bucket and chain were raised and lowered by means of a windlass and not by direct hauling over a block.

Among other finds from the waterlogged filling of 39 the well were fragments of twill woven with buff and purple threads, a pattern of coloring paralleled by a blanket in the Curator's collection. Also present was a small piece of red flock from an unidentifiable piece of upholstery. Recognizable plant life recovered included the following: seeds and pits from gourds, squash, plum, apricot, and peach; pine needles, and wood and twigs from grape vines, Virginia pine, red (sugar) maple, black walnut, cotton wood, mountain laurel, red cedar, mulberry, and red oak. These organic items were of considerable importance in that they provided the landscape architects with precedents for the kind of plant life to install in the vicinity of the tavern. (See Appendix II)

Well C has been reconstructed over the original shaft, and the unusual bucket has been reproduced.

WALKWAYS & YARD METALLING

Although sections of brick walkways were found south and east of the tavern, only that at the east (perhaps running between the tavern's Phase III addition and Outbuilding D.2.) being of eighteenth-century date. There is substantial evidence that during the colonial period the yard area between the tavern and the southerly outbuildings was paved with brickbats and domestic trash, the latter including oystershells, broken pottery and wine bottle bottoms. The compressed nature of this material suggested 40 that it had been deliberately and frequently rolled, perhaps with an iron garden roller of the type manufactured in the Spotteswood iron furnaces.

FENCELINES

Although large numbers of post holes were found in the course of the two seasons' excavations, very few of them could be safely associated with each other. There is much work still to be done on the dating of the individual hole and molds, and until that is completed it will be impossible to determine the various relationships. However, it would appear that there was no colonial fenceline between Buildings East A and B, though there may have been one extending south from the possible store structure that preceded Building East B.6 Three major fencelines were found on Lot 22. One ran east/west on the same line as the subsequent kitchen's north wall (Outbuilding C.1) and beside which the various caches of bottles were buried. This terminated at the northeast corner of Outbuilding B.1. The second also ran east/west but passed through the middle of the kitchen and continued immediately south of the south-east corner of Outbuilding B.1. It was clearly of nineteenth-century (post-kitchen) date, as also was another east/west line in the so-called paddock area south of the kitchen. (Fig. 1)

THE FIRE

As previously noted (page 22) there was evidence of a destructive fire in the form of debris spread in a yard surface layer between the kitchen (Outbuilding C.1.) and the tavern. (Fig. 1) This debris passed around the north-west corner of Outbuilding D.1., and beneath the tavern's Phase III southeast shed addition. Slight burning was found inside the kitchen north of the chimney, suggesting that the destruction had been confined largely to an area north of the colonial fenceline. The burning of the subsoil left no doubt that a fire had occurred on the site and that the burned debris had been spread over the heated area. However, it could not be proved beyond question that the two were related. It is conceivable, though highly unlikely, that after a fire occurred on Lot 22 in the area between the tavern and the site of the subsequent kitchen, debris from another and more intense fire was brought in from elsewhere and used as yard metalling. Evidence against this theory is provided by the Turlington's Balsam bottle from Well B. which matches a fragment from an identical bottle found in the bottom of the burned spread south of the tavern. (Pl. V) These are the only fragments of this early Turlington bottle form yet found in Williamsburg, and it is too much of a coincidence to suppose that both were found in burned deposits on 42 the same site and yet were unrelated. It is much more reasonable to deduce that they were both associated with the same fire, and if so, it is proved beyond doubt that that fire occurred after March 25, 1750 - the date molded on the side of the bottle from Well B. The bottle fragment from the burned spread7 did not come from the same part of the bottle and therefore is not, itself, dated. Further evidence of homogeneity was provided by the finding of widely scattered and heavily burned fragments of Chinese porcelain dishes of identical type. Fragments of burned pharmaceutical phials were also liberally distributed through the burned stratum, as were scraps of brass, including numerous buttons of the same ornamental type.

Although the burned debris could not be associated with a specific building, it is reasonable to conclude that a fire of considerable heat occurred on Lot 22 at some date not too long after 1750. Burned bricks were present in the upper courses of the Phase I tavern foundation in the vicinity of the bulkhead entrance, and it is tempting to conjecture that the superstructure burned in the mid-eighteenth century and that the tavern was rebuilt prior to Henry Wetherbun's death. This might explain the unusually heavy foundations on which the frame structure now rests. However, this remains no more than conjecture.

THE ARTIFACTS

These are to be the subject of a full report and will subsequently figure in a study intended to compare the finds from Wetherburn's Tavern with those form the Anthony Hay site and the Raleigh Tavern. At this point it is enough to mention only the most significant items, and to note that the site yielded more than 200,000 fragments of pottery, glass, metalwork, and small finds, excluding bones and nails.

The finds that promoted the greatest interest were undoubtedly the various deposits of once cherry-filled wine bottles found buried along the fenceline beneath the north wall of the kitchen (Outbuilding C.1.) against the east foundation of Outbuilding B.1. (dairy) and along the east wall line of the tavern. (See Fig.1 and page 20) Forty-seven bottles in all were involved, the largest single group (15) being against the east wall of the tavern at the southeast corner. (Pl. III) The cherries have been identified as Morello (a tree of English origin) and they would have been ripe in May or June, while the latest of the bottles is unlikely to date prior to 1755 or 1760. This date is therefore assumed to be that of the deposition of the entire assemblage of bottles, though were the one late bottle eliminated, the rest could easily date prior to 1750.

The best dated and most visually interesting collection 44 of artifacts came, as is invariably the case, from a colonial well shaft (Well C) and these have been discussed in an earlier section of this report (page 33). Apart from this deposit, the single most important assemblage came from a large but shallow depression (perhaps a tree hole) immediately south of the Outbuilding A complex. (Fig. 1) The material included a quantity of pottery, drinking glass fragments, broken wine bottles, as well as candlestick, a pair of tailor's scissors, a horseshoe and a hoe. The most potentially significant artifact recovered from this deposit was a wine bottle seal bearing the initials J.D. which may be that of John Doncastle who advertised in the Virginia Gazette (November 3, 1752) that he had "… taken the House of Mr. Wetherburn, in Williamsburg, to enter the first of March next, all Gentlemen, &c that please to favour him with their Custom, may depend on the best Accommodations…"

It has been argued that Doncastle rented an unidentified Wetherburn house and not the tavern. However, we do know that the term house was used to described Wetherburn's Tavern (Virginia Gazette, April 22, 1757). When Doncastle gave up tavern keeping in Williamsburg he announced "… the House I now live in is to Rented…" and that "… all the Household Furniture and Liquor [is] to be sold." (Virginia Gazette, August 15, 1755) . The association of House and Liquor could be construed as evidence that Doncastle lived and kept tavern on the same 45 premises, while the references to House in both his first and last advertisements could be to the same building, i.e., to "the House of Mr. Wetherburn." Thus the documentary evidence can be convincingly used to suggest that John Doncastle occupied Wetherburn's tavern from 1752 to 1755. As the JD bottle seal was found in a mid-eighteenth century context, it is more than tempting to identify the initials as those of John Doncastle and to look upon this archaeological clue as an endorsement of the documentary evidence.

Very few eighteenth-century rubbish pits or deliberate trash deposits were found on the site, thus strongly suggesting that the bulk of the tavern's refuse was carried away and disposed of elsewhere, perhaps in a communal city dump. However, there was no shortage of artifactual evidence, most of it derived from the yard layers south and east of the tavern. A wide range of wine glasses was found, running the gamut from the gadrooned-bowled goblets of the late seventeenth century to the air- and opaque-twist stems of the third quarter of the eighteenth century. The ceramics included a surprising quantity of Chinese export porcelain decorated in underglaze blue with overglaze red and gold embellishments. This was the kind of delicate porcelain that one would have expected to find in better class homes and its presence in such quantities on a tavern site was distinctly revealing. This, and other related evidence, has 46 been used to promote the possibility of the tavern's occasional or partial use as a coffee house. (See Appendix I).

Among the other classes of ceramics present, a particular importance is attached to the English white salt-glaze which included at least four "King of Prussia" plates, more than twenty plates with rare, molded floral rims, an early mold-decorated saucer, and fragments of two double-handled and double-spouted sauceboats. The delftware included fragments of inscribed bowls, and also a series of items having the same pattern, these comprising fragments of plates, bowls, cups, cans, saucers, and mugs. The Rhenish grey and blue stonewares offered only one surprise, a rim and wall fragment from a mug of seemingly unparalleled size akin to the large ornamental English brown stoneware tankards of the same period, i.e. the second quarter of the eighteenth century.

Small finds included cutlery, candlesticks, candle-snuffers, buttons, buckles, wine cocks, stirrups, wig curlers, tobacco pipes decorated with the British royal arms, and numerous tools and other items of hardware.

CONCLUSIONS

It is normal to end an archaeological report with a summary of the writer's conclusions. However, in the absence of a careful and certainly lengthy study of the relationship 47 between the archaeological, documentary, and architectural evidence, it is considered unwise to offer conclusions that are palpably inconclusive.

Footnotes

APPENDIX I

January 17, 1966

To: Mr. E. M. Frank

From: I. Noël Hume

Re: Archaeological evidence pointing to "Coffee-House" activity at Wetherburn's Tavern.

In the course of the 1965 season's digging on the above property the excavators were repeatedly struck by the quantities of ceramic fragments recovered which bore little obvious connection with tavern life. Particularly plentiful were sherds of Chinese export porcelain tea bowls, cans, saucers, slop bowls and plates delicately decorated in underglaze blue and overglaze red and gold, some in elaborate Imari motifs. So frequently did these pieces appear that an uneasy feeling developed that something was wrong and that either the tavern-keeper provided some additional service or that the popular idea of a tavern being a place for heavy drinking and eating does not hold up in Williamsburg.

In an attempt to resolve this question in one way or another, Mrs. Noël Hume has been scheduled to prepare a study based on the inventory and archaeological evidence from the Hay Cabinet Shop site (there being evidence that many of the artifacts came for the Raleigh), the Raleigh itself, and from Wetherburn's Tavern.

49She is to couple the artifactual evidence with that of related inventories and compare the results with inventory and (where available) artifact evidence from purely domestic sites elsewhere in town. Unfortunately, this project has not been started, and it is not expected that the results will be forthcoming at least until the Wetherburn excavations are concluded in 1967. In the meantime, therefore, the following comments stem only from the limited information currently available and should not be considered as anything approaching a definitive report. Nevertheless, the solid evidence now extant and the tentative conclusions drawn from it, do suggest the possibility that coffee and tea were served at Wetherburn's Tavern, perhaps in a room set aside for that purpose.

The Research Department's report on the coffee houses of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries1 provides an extensive assemblage of documentation for the existence of coffee-houses in Williamsburg, though it has rarely been possible to identify the exact locations. It would appear from this report that although some buildings were used as coffee-houses one year and as taverns the next, others served both roles at the same time.

50Thus, in discussing the establishment now known as Christiana Campbell's, it is stated that "In 1765 Mrs. Jane Vobe was operating this house behind the Capitol - apparently as a coffeehouse. In April of that year, a French traveller stayed there, describing his visit as follows:

' on our arival we had great Difficulty to get lodgings but thanks to mr sprowl I got a room at mrs vaube's tavern, where all the best people resorted.'"The report goes on to quote further from the Frenchman's account of his impressions of Williamsburg, saying:

"In the Day time people hurying back and forwards from the Capitoll to the taverns, and at night, carousing and Drinking In one Chamber and box and Dice in another, which continues till morning commonly, there is not a publick house in Virginia but have their tables all batered with ye boxes..."2Taken at face value, this quotation can be construed to tell us no more than that Mrs. Vobe kept a tavern and that in Williamsburg taverns in general, gaming went on in one room and liquor drinking in another. The report suggests, however, that Mrs. Vobe's establishment was a coffee-house and that "this building had separate rooms for drinking and gaming." 51 If we accept this interpretation we have reason to conclude that coffee-houses could be divided up into specific rooms for purposes other than those directly associated with coffee or tea drinking, and furthermore, a visitor could obtain lodging in the aforesaid coffee-house and find it indistinguishable from a tavern.

Irrefutable evidence that American coffee-houses did double as taverns is provided by a reference to a 1781 New York advertisement describing the services to be offered by the "City Tavern and Coffee House" wherein one might enjoy "Breakfast from seven to eleven; soups and relishes from eleven to half-past one. Tea, coffee, etc. in the afternoon as in England."3 The question that has to be answered is whether or not such a studied combination existed in Williamsburg.

The historians of coffee-houses are generally agreed that they began as places where men gathered to drink coffee, converse, do business, and read newspapers. In the early eighteenth century they expanded their services to include the provision of liquor, though this seems to have been restricted to cordials and the like. When the clientele began to band themselves together into clubs4 as they did 52 from the early eighteenth-century onward, the coffee-houses suffered a decline. But it is important to note that the ubiquitous eighteenth-century clubs not only inflicted themselves on the coffee-houses, but on the taverns as well. It is a mistake, therefore, to suppose that any paintings, prints, or drawings of carousing club members automatically depict them in coffee-house settings. The research report's identification of Hogarth's famous "Midnight Modern Conversation" (c. 1732) as a coffee-house scene could be used along with the Frenchman's Williamsburg description to suggest that as wild parties were thrown in those houses as there were in taverns. But in truth there is no evidence that the "Midnight Modern Conversation" has a coffee-house locale. Moreover, it would seem on the basis of those eighteenth-century illustrations which bear irrefutable coffee-house identifications that many more coffee cups and bowls appear on the tables than do liquor glasses or bottles, and that although the customers might throw the contents of their cups in each other's faces, drunken carousing was reserved for the taverns.

As the research report points out, meals were served in Williamsburg coffee-houses, as evidenced by William Byrd who, on September 20, 1711, went to dinner there and ate "a fricassee of chicken." On November 11th of the same year, he ate chicken pie and apparently took his bottle of wine with him. On November 29th, he "ate some toast and 53 butter and drank milk tea on it." It should be noted that on other occasions he referred to drinking tea at the coffee-house and it seems that either tea or coffee were commonly consumed there. On yet another occasion (December 24, 1711) Byrd ate "some beef for dinner" at the coffee house and on March 31, 1712, he specified "cold roast beef."

From the foregoing references we may deduce that meals were served at the coffee-house frequented by William Byrd, but as a rule he ate larger meals (?) before repairing to it; similarly he did most of his drinking elsewhere and occasionally arrived the worse for wear. His visits occurred at all times of day, but most frequently in the evening and sometimes lasted far into the night. The evening sessions generally included games of cards and dice, but at other times Byrd notes a deal of conversation, and the writing of one letter. It is significant that on October 27, 1709, Byrd turned up "very merry" from drinking cider, and proceeded to pull Colonel Churchill out of bed. Thus we know that at least one Williamsburg coffee-house provided lodgings - as did the taverns.

It is clear that when Byrd was writing there was a difference between taverns and coffee houses, and from the Diary of George Washington it is apparent that a distinction persisted until at least 1773. Between the 19th and 29th of 54 November of that year he spent six evenings "at the Coffee House", five of them after dining elsewhere. Furthermore, on three occasions he had first eaten at the Raleigh, suggesting that this particular coffee house did not provide dinner, but that it did offer something not to be found at the Raleigh - perhaps a less bibulous atmosphere.5 But if the previously quoted 1765 reference to Mrs. Vobe's establishment is to be accepted (as the research report indicates) as a description of coffee house life, we must assume that at least some coffee-houses were indistinguishable from taverns. If this be so, it is not unreasonable to suggest that taverns would also provide coffee-house services, e.g. coffee, tea, light meals, newspapers, gaming, club rooms. The question that we can then ask is whether Wetherburn provided such facilities in the mid-eighteenth century. His inventory6 might be used to suggest he did.

In the Bull Head Room we find one mahogany tea table, and in the Great Room were a tea kettle, two coffee pots and a chocolate pot. The list of his silver included one large tea kettle, two tea pots, 19 teaspoons and a milk pot. But more significant was his list of ceramics among which were tabled "1 Tea Pot and Stand 1 Slop Bason Sugar Dish Tea 55 Cannister 7 Cups 8 Saucers Spoon and Tong stands 6 Coffee Potts and 1 Plate" having a total value of 11.6.0d. Listed separately were "1 Set white flowered China", "6 Enamelled cups and Saucers 1 Cup and 4 Saucers Do", "5 Red and White Cups and 4 Saucers", "5 Blue and White China Bowls" plus four of the same in red and white. There were also "2 Japan Mugs" and "A Parcel of Old China." This is a good range of tea and coffee ware (though not enormous), but the reference to no fewer than six ceramic coffee pots in addition to one of silver and two others of unspecified materials7 is certainly more than would be needed by a single family. The visibly best equipped of the coffee-house rooms illustrated in the research report (facing p. 2, c. 1705) shows four pots heating in front of the fire and one in use.

The excavated ceramics so far recovered from Wetherburn's tavern (excluding approximately 35 per cent temporarily stored away and not available for study) comprise 52 tea or coffee bowls, 47 saucers, 7 tea or coffee cups, 10 teapots, 13 slop basons, 1 tea caddy. These figures break down as follows: 56

| Tea/Coffee bowls | Tea/Coffee cups and cans | Saucers | Teapots | Tea Caddy | Slop Basons | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese Porcelain | 29 | 6 | 27 | 4 | 6 | |

| English Porcelain | 4 | 6 | 2 | |||

| White Saltglaze | 13 | 11 | 6 | 1 | 5 | |

| Scratch-Blue | 4 | 3 | ||||

| Delft | 2 | 1 | ||||

| TOTAL | 52 | 7 | 47 | 10 | 1 | 13 |

It should be noted that this brief survey does not include milk pitchers nor does it encompass the considerable number of delft bowls whose diameter makes it debatable as to whether they can fairly be classed as slop basons. The figures as a whole may be said to be conservative in that the 35 per cent of the collection not currently available contains a high proportion of groups belonging to the Wetherburn period. It should also be noted that the present, very preliminary count includes material from all groups from the top soil down, but excludes those wares (e.g. creamware, Wedgwood green, pearl ware) which were manufactured after Wetherburn's death. It is also highly significant that this large assemblage of tea/coffee oriented ceramics comes not from wells or rubbish pits where the 57 bulk of Wetherburn's trash would have been deposited, but from the odd sherds scattered around the ground surfaces adjacent to the tavern.

The tally of glassware recovered from the same deposits as the ceramics is as follows:

| Jelly glasses | 9 |

| Tumblers | 19 |

| Wine glasses (baluster stems) | 11 |

| Wine glasses (drawn stems) | 10 |

| Wine glasses (air and opaque twists) | 16 |

| Wine glasses (various) | 13 |

| TOTAL | 78 |

All the stemmed glasses listed above are temporarily classed as wine glasses, but it is certain that the smaller examples could have been used for cordials. There are, in addition, a number of salver fragments, but there is yet no information on the number of individual items represented. Furthermore, the glass count is derived from stems and not from bowl fragments whose inclusion would certainly result in duplication.

Wetherburn's inventory lists the following glassware, a table surprisingly short of wine glasses; the list of glassware is as follows: 58

| 8 | Wine Decanters |

| 19 | Syllabub Glasses |

| 62 | Gelly Do (Jelly glasses) |

| 14 | Sweemeat Glasses |

| 21 | Wine and Cyder Do |

| 9 | Glass Salvers |

| 1 | Glass Bowl and Ladle |

| 2 | Candle Glasses |