Historical Archaeology, Identity Formation, and the Interpretation of Ethnicity

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0385

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1999

Historical Archaeology, Identity Formation, and the Interpretation of Ethnicity

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS

Historical Archaeology, Identity Formation, and the Interpretation of Ethnicity

Colonial Williamsburg Research Publications

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Printed by

Dietz Press

Richmond, Virginia

© 1999 by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Printed in the United States of America

Graphic Design and Layout: Gregory J. Brown

Assisted by: Tami Carsillo

Cover Design: David Brown

Cover illustration (left to right): Austenaco or Ontasseté, from a 1762 engraving (courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution); costumed interpreter at door of reconstructed slave quarter at Carter's Grove Plantation (photo by Dave Doody, courtesy Colonial Williamsburg Foundation); Plaster model of Francis J. Williamson's statue of Joseph Priestley, on display at Priestley's final home in Northumberland, Pennsylvania (photo by Dave Doody, courtesy Colonial Williamsburg Foundation).

Table of Contents

| Page | |

| Acknowledgments | iii |

| Foreword: Robert L. Schuyler, University of Pennsylvania | v |

| The Exploration of Ethnicity and the Historical Archaeological Record: Garrett Fesler, University of Virginia, and Maria Franklin, University of Texas, Austin | 1 |

| Industrial Transition and the Rise of a "Creole" Society in the Chesapeake, 1600-1725: John Metz, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation | 11 |

| Where Did the Indians Sleep?: An Archaeological and Ethnohistorical Study of Mid-Eighteenth-Century Piedmont Virginia: Susan A. Kern, College of William & Mary | 31 |

| Buttons, Beads, and Buckles: Contextualizing Adornment Within the Bounds of Slavery: Barbara J. Heath, Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest | 47 |

| "Strong is the Bond of Kinship": West African-Style Ancestor Shrines and Subfloor Pits on African-American Quarters: Patricia M. Samford, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources | 71 |

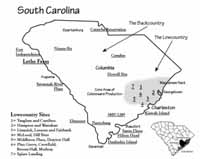

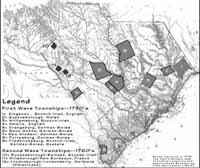

| Stirring the Ethnic Stew in the South Carolina Backcountry: John de la Howe and Lethe Farm: Carl Steen, Diachronic Research Foundation | 93 |

| In Search of a "Hollow Ethnicity": Archaeological Explorations of Rural Mountain Settlement: Audrey J. Horning, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation | 121 |

| Dimensions of Ethnicity: Fraser D. Neiman, Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation | 139 |

Acknowledgments

The editors would like to thank Cary Carson for allowing us the opportunity to publish this work through Colonial Williamsburg's new research monograph series. We are grateful to both Carson and Marley R. Brown III for their enthusiastic support of this project. We would never have reached this point had it not been for Greg Brown, who had the unenviable job of putting everything into PageMaker and ensuring that this volume was ready to go to press. Thank you, Greg. David Brown took on the job of designing the cover with little warning, and under much duress. Thanks for bailing us out, Dave.

This volume was the result of a session on ethnicity held at the 1996 Society for Historical Archaeology conference in Cincinnati.

The original panel included Margot Winer, Minette Church, and Jeff Watts-Roy. We thank these individuals for their participation in the session, and for helping to provide the basic foundation from which this volume grew. Fraser Neiman and Robert L. Schuyler served as discussants on the panel, and we deeply appreciate their initial feedback on all of the papers, and on their willingness to contribute to this volume. It is to the authors—Carl Steen, Audrey Horning, Barbara Heath, Susan Kern, Patricia Samford and John Metz—that we are most grateful. Thank you all for staying committed to this project, for your patience, and for coming through as strongly as you did.

ivForeword

Robert L. Schuyler, University of Pennsylvania

Since 1980 historical archaeology has expanded its subject matter by moving beyond basic culture history to emphasize a number of central research topics. These themes are not limited to the field of historical archaeology and archaeologists, both prehistoric and historical, are merely following the lead of current scholarship, especially the work of historians and some cultural anthropologists. Topics covered, or potential future additions, include ethnicity, class, gender, age cohorts, race, occupations, and a series of categories (such as nationality, religion and political groupings) that may or may not be subsumed under these more generalized types.

One of the first research subjects selected by historical archaeologists was ethnicity, and it continues to occupy the center of topical research, although the study of class, a related subject, is growing in popularity. This set of papers by six younger scholars all approach ethnicity as both a significant factor in human culture history and a difficult problem for archaeologists. Is ethnicity a surface phenomenon, fully active on a conscious level of behavior, purposely manipulated in a fluid environment of power and class—a suit of cultural clothing worn and changed at will and only having meaning relative to other groups otherwise clothed? Or, is ethnicity a deeply rooted, stable phenomenon grounded in enculturation and history—a manifestation of the bedrock of culture itself?

Which end of this spectrum of definitions a researcher selects will have a major impact on how one approaches the topic from fieldwork to synthesis and interpretation, as well as how successful archaeology is in recognizing material manifestations of ethnicity.

Six case studies are offered in this monograph. They range across the formation of "creole" society in colonial Virginia, Native Americans interacting with Anglo-American power centers, the ability or lack of ability of enslaved Africans to preserve or de novo generate their own cultural identity, or more specifically, to maintain their most basic beliefs, to a discussion of ethnic variation internal to Euro-American culture, a theme that has been relatively neglected. This range of essays takes the reader on a quite varied and fascinating exploration, but one unified by the same cultural region in North America. Virginia and South Carolina have both been well explored by both historians and archaeologists. Metz, Kern, Horning, Heath, Samford and Steen are all to be congratulated for an insightful if tentative set of essays.

Historical Archaeology, Identity Formation, and the Interpretation of Ethnicity, because of its authors and two organizers-editors, is a solid contribution to the growing literature on the ability of historical archaeologists to explore one of the most basic human categorizations to appear since the rise of complex societies.

The Exploration of Ethnicity and the Historical Archaeological Record

Garrett Fesler and Maria Franklin

Part 1: Introduction

Several years ago while visiting a friend excavating a sugar plantation in the mountains of Jamaica, a middle-aged man approached me at a rural taxi stand. "Who you?" he asked rather threateningly. I was not sure exactly what he wanted to know, so I told him I was an American from the United States. "No, who you?" he said again. I explained I lived in the state of California. "No, no, who you?" he implored while stepping toward me and brandishing his machete. Since I was wearing a Los Angeles Dodgers baseball cap, with some alarm I gestured to it and told him I was from Los Angeles. The man laughed, turned to the twenty or so people gathered around us, and said, "See, this bloody ras don't know who he is!" Indeed, the joke was on me. Yet, although the man took the opportunity to ridicule an outsider and in doing so, to advance his reputation within his community, in essence, we as historical archaeologists ask that same simple question of the people who formed the archaeological sites we excavate, "Who you?" And all too often, no simple answer materializes and we end up feeling as lost and confused as I did with the man at the taxi stand.

Some seventeen years ago Robert Schuyler compiled and edited fourteen essays in a volume entitled Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America: Afro-American and Asian American Culture History (1980). As its title suggests, the book introduced a variety of historical archaeological treatments of the topic of ethnicity, exclusively focused on African- and Asian-American sites. The book, like this compilation, was in part a product of its time. It was published while Iran held 52 Americans hostage, while Nelson Mandela was just another forgotten prisoner in an entrenched South African system of violent apartheid, and while Dublin, not Beirut or Sarajevo, was the world's most notorious ethnic battleground. Almost twenty years later, ethnicity remains at the forefront of the social, political, economic, and religious agenda around the globe, although the sites of its turbulence continue to change. Dozens of clashes motivated by ethnic issues occur everyday, resulting in ethnic convergence at its most deadly. It would be comforting to think that the distance between "ethnic cleansing" in Bosnia in the 1990s and the expressions of ethnic identity on an eighteenth-century Virginia plantation or in the hollows of Depression-era Appalachia are hardly comparable. Yet the germ of conflict in both locales, separated as they are by time and circumstance, is distinctly ethnic.

The word ethnicity, and its attendant terms ethnic group and ethnic identity, are relatively new idioms still in semantic flux. The term ethnicity emerged in the mid-twentieth century, but the exact origin is unknown (see Sollors 1996, footnote 2). The word only first appeared in English dictionaries in 1972 (Glazer and Moynihan 1975:1), while the term ethnic group and the adjective ethnic first surfaced in the latter nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth century (Sollors 1996, footnote 2). The root of ethnicity, ethnic, is derived from the Greek word ethnos or ethnikos which at different times translated to "heathen" or "pagan," and later as "nation" or "people," and in more general terms as "others" (Banks 1996:5; Eriksen 2 1993:3-4; Sollors 1996:x-xi). In the United States during the Second World War, "ethnics" was used "as a polite term referring to Jews, Italians, Irish and other people considered inferior to the dominant group of largely British decent" (Eriksen 1993:4). For social scientists since mid-century, the term has evolved into a referent for groups of people who consider themselves or are labeled by outsiders as culturally distinctive, sometimes conflated with other terms such as "race" or "minority" (Eriksen 1993).

Today there exists as many working definitions of ethnicity as there are groups who claim to possess a distinctive ethnicity (see, for example, Banks 1996:4-5). More than one hundred ethnic groups can be found in the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups compiled in 1980, and since then more surely have surfaced (Thernstrom et al. 1980). The term ethnicity has become so malleable and vague, some claim the expression to be virtually drained of its utility (Banks 1996:10). Yet, still the word and its multiple meanings persist, and have become part of the anthropological and archaeological language.

The debate which has dominated the anthropological discourse on ethnicity for several decades is between two schools of thought, primordialism and instrumentalism. Primordialists tend to acknowledge the core of ethnic attachment to be ineffable, emotional sentiments or psychological bonds between people centered on blood ties (Hutchinson and Smith 1996:8). Instrumentalists counter with a social constructivist view of ethnicity that places ethnic origin as a manifestation solely of culture, which is malleable and interchangeable depending upon common needs and often the sociopolitical setting (Hutchinson and Smith 1996:9). Dyed-in-the-wool primordialists can be criticized for biological deterministic leanings, while hard-core instrumentalists tend to disavow the very real emotional dimensions of ethnicity (see Jones 1997:68-72, 7679). Somewhere between the two extremes of primordialism and instrumentalism resides a broad-based approach to ethnicity which simultaneously acknowledges both cultural and seemingly unexplainable psychological ethnic ties which bind groups of people together (see Keyes 1976). Most recently, elements of practice theory have been utilized to suggest that "the construction of ethnicity is grounded in the shared subliminal dispositions of social agents which shape, and are shaped by, objective commonalities of practice" (Jones 1997:128).

In this volume we hesitate to become mired in adding another carefully crafted definition of ethnicity that toes the line between the primordial and instrumental camps. Instead, we encourage historical archaeologists to seek their own working definitions, an approach taken by each of the authors in this volume. The multifaceted nature of the issue which is apparent in the six essays here, hopefully illustrates the merit of embracing the paradoxical nature of ethnicity as a means for broadening the inquiry into the issue. Rather than mourn the fact that "the relationship between artifacts and ethnicity or culture is ambiguous and evanescent" (Upton 1996:5), we celebrate the challenge that the complexities of ethnicity and material culture pose.

Like today, ethnicity possessed differing meanings for different people in the past. Each historic archaeological site offers the opportunity to explore the varying ways in which people created, altered, and used ethnicity for themselves and sometimes in contrast to others. Thus, the question to be asked while excavating historic archaeological sites is not how past peoples fit into our rigid contemporary definitions of ethnicity, but rather how people in the past constructed ethnic identities and how the identities worked and for what reasons (e.g. McGuire 1982). The 3 results of such investigations may prove that other social dimensions dominated, or that ethnic identity was enmeshed in complex ways with other forms of identity such as gender or class (Jones 1997:85; McGuire 1983). By questioning the formation, maintenance, and use of ethnic identities, historical archaeologists can at least avoid some of the more damaging trappings of a monolithic, positivistic, and static version of ethnicity that has tended to dominate the historical archaeological treatments of the topic (Upton 1996), including some of the essays in Schuyler's volume.

Schuyler and his colleagues posed a key question in 1980 that still resonates today: "Is ethnicity … recognizable in the archaeological record?" (viii). In the intervening years, a more relevant question has emerged. Rather than framing the issues of ethnicity and ethnic groups as an issue of visibility in the archaeological record, we suggest that a more fruitful path is studying the concept of ethnicity and ethnic affiliation as a tool used by various individuals and groups to facilitate practical ends. Instead of searching for the static patterns and correlates of so-called ethnic identity, we must recognize that ethnicity and ethnic identity served as a dynamic agent of social and cultural negotiation. All peoples and the objects through which they manipulate daily life are imbued with ethnic overtones, whether it be in the meals they consume, the clothing they wear, or the spaces they inhabit.

Some 25 years after writing his celebrated introduction to Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Difference, Fredrik Barth, the anthropologist largely responsible for placing ethnicity at the forefront of the discipline, encouraged researchers to "attend to the experiences through which [ethnic identity] is formed, it is not enough, as one thought with a simpler concept of culture, to make a homogenizing inventory of its manifestations." (Barth 1994:14). Given Barth's encouragement, perhaps the more robust question at hand is: Can the findings of historical archaeologists contribute to a fuller understanding of the social uses of ethnic identity? By framing our focus on the processes of ethnic group formation, maintenance, and dissolution, rather than the end products of ethnic display, we believe historical archaeological contributions to the issue are greatly empowered.

Several recent scholars suggest that historical archaeologists are uniquely poised to investigate ethnicity (e.g. Deetz 1995; Jones 1997:27; McGuire 1982:161; Staski 1990:121-122). Thus far, however, "the existence of historical references to specific ethnic groups has resulted in the perpetuation of the 'ethnic labeling' of sites and objects" rather than more in-depth revelations of ethnic uses and abuses (Jones 1997:27). Although we might wish it to be so, simple, one-to-one correlations of ethnic identity do not exist (Jones 1997:140). Jim Deetz recently characterized the search for individual "ethnic" objects as "something of a red herring" (1995:9). Indeed, many have been distracted from the real work of ethnic understanding, entranced by the luster of mere baubles. Instead, Deetz encourages archaeological practitioners to ask how "ethnic groups manage their ethnicity in the face of adversity" and to consider each culture as an integrated whole rather than piecemeal (1995:10).

Unfortunately, the historical archaeological literature on ethnicity tends to be top heavy with assessments of items such as blue beads, cowrie shells, opium pipes, distinctively butchered animal bones, dietary products, quantities of buttons and the like with the inference that these constitute ethnic markers for some groups (e.g. Etter 1980; Kelso 1984:201-202; Klingelhofer 1987; McKee 1987; Pearce 1993; Stine et al. 1996). These objects certainly meant something to 4 the people using and creating them, and may relate in some way to discrete groups of ethnically related individuals. Yet, like most archaeologists, we steadfastly reject the "artifact=ethnicity" premise, not because many transplanted Africans, Chinese, Italians, Germans, Mexicans, Irish, etc. did not retain distinctive identities and practices related to their perceived ethnic affiliation, but because the nature of archaeological evidence of ethnicity is necessarily complex, situational, historically contingent, and culture-driven (Verdery 1994). Given this, we suggest that finding so-called "ethnic markers" at a site is not the termination of inquiry, but rather initiates the creation of questions which focus on the meaning, construction, and expression of ethnic identity for a variety of specific peoples in various settings.

In addition to encouraging archaeologists to seek the visibility of ethnicity in the archaeological record, Robert Schuyler in 1980 recognized the connection of ethnicity and issues of political domination and power, suggesting, "Ethnicity has little meaning until complex structures arose based on political domination" (viii). Indeed, issues of ethnic identity in more recent archaeologies "are often overtly political in nature" (Jones 1997:10) and issues of nationalism are intimately tied to structures of ethnic identity (see Barth 1994; McGuire 1982; Shennan 1989; Verdery 1994; Williams 1989). Thus, as Brackette Williams stated recently, "'ethnicity' is … a matter of power differentials between two or more groups in contact producing one or more additional groups, which then confront the originators" (1992:609; see also Jones 1997). Moreover, Adrian Praetzellis et al. remind us that in most contexts ethnicity only emerges in contrast to a dominant cultural tradition that functions as a lens through which we can see emulation or rejection, ethnic and otherwise (1988:193).

Throughout the literature on ethnicity, both archaeological and anthropological, the issue of what Fredrik Barth (1994) calls "social dichotomization" or "difference" is paramount. Essentially Barth recognizes that ethnicity is a method of organizing cultural differences so as to create the criteria for which to include or exclude members Barth (1969). In our zeal to recognize and understand ethnic difference, however, Katerine Verdery warns us of the dangers of accepting difference uncritically. Verdery worries that the potential uses and abuses of the heterogenization of society marks a movement toward a "new essentialism" which threatens to diminish multiculturalism. The possible misuses of concepts of ethnic difference are symptoms of the restructuring of world capitalism as it attempts to cope with recent crises and threats to its hegemony (Verdery 1994:51-55). Thus the concept of ethnic difference, whether it be at issue on a college application form, in a repatriation dispute, or a fundamental element of social organization on an eighteenth-century plantation, cannot be divorced from the larger social milieu in which historical archaeologists presently function.

We recognize that the theoretical discussion of ethnicity may well be an exercise in rhetoric unless it can be translated into practical definitions for archaeological use. Therefore, like the case studies compiled by Robert Schuyler almost twenty years ago, we hope the studies herein provide a set of blueprints from which to assist historical archaeologists as they continue to wrestle with the intertwined issues of identity in the past and the many meanings and uses of ethnicity.

Part II: Six Authors, Six New Insights

The papers presented in this volume underscore historical archaeology's sustaining 5 interest in ethnicity and culture. Moreover, they exemplify the move by a growing number of archaeologists towards more thoughtful and critical analyses of what are now more fully appreciated and recognized as inherently complex processes of identity construction. This holds true for the six authors herein, even though they variously differ on points ranging from their working definitions of "ethnicity," to their interpretations of how and why individuals and groups set themselves apart from others. The following discussion summarizes the diverse perspectives brought to bear on the question of how people in the past devised meaningful ways to negotiate both their sense of individuality, or "self," and their collective sense of belonging to a group.

To start, on a fundamental level the authors all seem to agree that ethnicity is socially constructed, from both within and without the group. Further, they all variously recognize—although they differentially emphasize— that culture and tradition, place of origin, common ancestry and history (whether real or imagined), and diverse physical attributes all combine to forge one's ethnic identity. Horning, Metz, and to a lesser extent, Steen, move beyond this basic definition in considering the role of power in the creation of ethnic groups. As Horning posits, "ethnic groups, by definition, only exist because of their relationships with other groups."

These relationships are often fraught with tension as people with divergent interests coalesce into different factions and compete for what ultimately boils down to dominance or self-determination. For example, Metz asserts in his study of English colonists that their move towards embracing a distinct, Anglo-Virginian ethnicity was largely due to their attempts to vie for control over their limited resources. Similarly, Steen acknowledges that the need to preserve the institution of slavery, and hence maintain control over Africans and blacks, made ethnic group formation pertinent to white colonists. Having each stated their case on what they mean by "ethnicity," the six authors then move in different directions, guided by varying research questions.

Metz's article deals with a crucial period in American history, when the system of indentured servitude shifts in centrality, giving way to the rise and establishment of the African slave trade. Metz focuses on the population most responsible for changing the nature of the Chesapeake labor force: Virginia's native-born, or "creole," landholders and political leaders. He contends that it is their unwillingness to be completely dependent on England for finished goods, among other things, that impels them to invest in local trades and manufactured goods. His main body of evidence is the archaeology of brick-making technology.

Metz posits that while England's main interest lay in Virginia's tobacco economy, Virginia creoles understood that tobacco monoculture was not necessarily in their best interest. Colonists re-envisioned their political and economic goals, and a growing number of native-born English subjects viewed themselves as a different sort from their English- born counterparts. Influenced by Randall McGuire's work, Metz interprets this growing division, manifest in an alternative social identity (i.e. "creoles"), as evidence of ethnogenesis brought about by group conflict. Through a careful synthesis of archaeological data on Chesapeake brick production, Metz demonstrates that this form of local manufacture is but one example of the attempt by Anglo-Virginians to move towards self-sufficiency, thus challenging England's dominance. It further attests to their growing resolve to plant themselves permanently in Virginia by building more permanent shelters than were previously common.

6Like Metz, Horning takes into account how power relations were key in forging certain aspects of Appalachian identity and group formation. She adds a fascinating dimension to her study by considering how not only emic but etic constructions of ethnicity were variously accepted by hollow residents as, in Fesler's words, "dynamic agents of social and cultural negotiation." Horning effectively argues that the imposition of negative, "hillbilly" stereotypes to "hollow folk" from the Blue Ridge Mountains was clearly motivated by deceitful politics aimed at removing longtime residents from their land. Horning strikes a blow to these persistent stereotypes, demonstrating with architectural and archaeological evidence that Appalachian families maintained vibrant and diverse communities that did, in fact, have knowledge of the outside world. Importantly, Horning's study serves as a prime example of how ethnic identity is situational. Citing oral testimonies, Horning shows how certain members of this group ably adopted the stereotypical, characteristics of "backwoods" ethnicity to their advantage in dealing with outsiders. As she observes: "Clearly, the creation of ethnicities can be a fluid and rapid process, readily able to traverse the boundaries of the emic and the etic."

A recurring theme in this volume is the caveat against using material culture as "ethnic markers." It is a message oft-cited, but less often are we given alternative, constructive ways to interpret artifacts that are indeed associated with ethnic groups. Kern does just this, in a similar fashion to Horning, by showing that just as identities are fluid and relational, so are the meanings and values we attach to objects that play a significant role in shaping identities and social relations.

Kern chooses as her focal point an assemblage of Native American artifacts that many historical archaeologists encounter, but are typically hesitant to attempt an explanation for when they are recovered from "non-Indian" sites, such as Shadwell plantation. In contrast, Kern seizes the opportunity to investigate what she perceives as potential evidence for interactions between diverse ethnic groups within the Virginia frontier. Creating a narrative from historical sources, Kern helps us to visualize a series of encounters between enslaved blacks, whites, and Indians. In doing so, she demonstrates the role that material culture played at different scales. On one hand, objects were visible in the social and political arena, as different ethnic groups worked to position themselves via status. On a smaller scale, material goods exchanging hands between individuals may have been central in forging personal relations, as Kern suggests may have been the case with Indians enjoying the hospitality of enslaved blacks at Shadwell.

Kern presents us with multi-layered interpretations of ethnic and social identities in motion, shifting to accommodate different circumstances. She does archaeology a great service in underscoring just how complex and fluid these meetings between different individuals and groups may have been, and therefore, how difficult it must be to discern the meanings of material goods associated with these exchanges.

In her innovative work on the enslaved community of Poplar Forest, Heath deals with an essential aspect of identity formation and maintenance: its outward display in the form of dress and adornment. Her article is a departure from most previous research on the emergence of African-American identity in that she begins with the premise that there did not yet exist a sense of African- American ethnicity during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Heath points out that during these early years, "African-American society" was in fact a heterogeneous mix of blacks and Africans that did not necessarily view themselves as 7 a group. Her focus is therefore on the events preceding the transformation to a more definitive African-American ethnic group, when a myriad of African-born peoples, along with an American-born population of numerous racial categories, actively sought to forge individualized identities.

By taking this route, Heath does not confine her analysis to "ethnicity" or "culture." Her study of the relationship between identity and adornment on a personal level pulls in other factors that crosscut cultural values such as occupation, gender, and enslavement. This is perhaps the greatest strength of her interpretation, in that the individuals of her study are not reduced to one-dimensional characters, devoid of multiple subject positions. Although Heath questions whether archaeological analysis can be used to address questions regarding identity and the role of adornment within enslaved communities, she nonetheless effectively demonstrates its potential to do so.

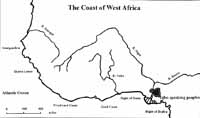

Samford's provocative article on the use of some subfloor pits as ancestor shrines will undoubtedly encourage a number of us to more closely scrutinize the contents of Chesapeake "root cellars." Like Heath, Samford's methodology includes the careful contextualization of all aspects of her case study. She begins with a historical and demographic discussion of the West African groups who were most likely to be present in the Tidewater during the eighteenth century, and who might have been likely to use pits as ritual spaces. Notably, Samford centers her attention on the Igbo, Ibibio, and Yoruba peoples. This is a refreshing departure from other work on early African-American spirituality which has tended to rely heavily on drawing analogies from Kongo-related beliefs.

Samford's persuasive argument that certain root cellars may indeed have served as ancestral shrines is strengthened by her cautious choice of examples. The two root cellars in question both contained artifacts that Samford argues were left in primary context. Moreover, her rigorous analysis of patterns pertaining to placement, artifact association, and symbolism serves as a prime example of contextual archaeology. In the end, Samford successfully manages to take two of the most popular subjects of study in African-American archaeology, i.e. spirituality and root cellars, and adds a fascinating dimension to the discussion.

Steen is also to be applauded in bringing an air of originality to the interpretation of another well-known topic in historical archaeology: colonoware pottery. Like the other authors in this volume, Steen recognizes a strong association between material culture and ethnicity. Yet Steen's objective is to demonstrate that establishing specific ties between ethnic groups and archaeological evidence (i.e. defining ethnic markers) is not only difficult at best, but self-defeating and reductionist at worse.

Steen uses the examples of colonoware and clay-walled house remains to argue that the accepted wisdom that these objects are solely the products of enslaved South Carolinians is too simplistic. By combining both regional and site-specific demographic, historical, and archaeological data, Steen explains that other ethnic groups could each potentially have also contributed to their production. His research underscores the fact that the social and cultural boundaries we as archaeologists so fervently draw around different groups often get drawn around their material culture as well, and this does not generally reflect past realities. People of very different backgrounds and circumstances exchanged ideas, transforming themselves and others in the process. As Steen posits, they created a variety of "creole" cultures. Thus, no single, over-arching interpretation could possibly fit every scenario where clay-walled 8 houses or colonowares were used. Consistent with this thesis, Steen pursues more site-specific explanations. He summarizes his finding as follows: "…the Lowcountry creation of colonoware is not something that is pan-African or even pan-African American. It is a local phenomenon…created and used within particular social and cultural circumstances."

Steen's research exemplifies the value of comparative, multi-scalar research, and will hopefully encourage others to "think locally" rather than attempt blanket explanations which tie specific ethnic or racial groups to the creation and use of specific objects.

Concluding Remarks

It will come as no surprise that the theoretical insights and interpretive schemes presented in this volume move in different directions. What binds these articles into a coherent, unified volume, however, are the authors' concerted efforts to discard the diehard "ethnic marker" exercises, and to engage in more rigorous and sophisticated analyses of the relationship between identity and material culture. Importantly, these authors privilege the archaeological record, and demonstrate that the potential for constructing viable and engaging interpretations based on the physical evidence is great.

Ethnicity remains an important topic in historical archaeology despite the recent, and legitimate, critique that it has tragically managed to displace race and racism from much academic discourse. Historical archaeology is no exception, and since Robert L. Schuyler's important, edited volume "Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America" appeared in 1980, ethnicity has remained a central subject in our discipline while race is not and never has been. Perhaps this is because it is seemingly easier to connect "ethnicity" (often interpreted as including "culture" or "tradition") to the archaeological record than "race." Whatever the reason, the study of ethnicity and that of race can, and should, co-exist in our study of the American past, for groups and individuals consciously identified themselves and others both along what we today refer to as racial and ethnic lines.

In ending, the authors in this volume have confirmed that researching ethnicity is indeed still a worthwhile endeavor for archaeologists. More importantly, they have demonstrated that as our understanding of the complexity of the individuals we study grows along with our recognition that the material record is far more complicated than we may have realized, this leads not necessarily to utter confusion, but to fuller visions of experiences once lived.

References Cited

- 1996

- Ethnicity: Anthropological Constructions. Routledge, New York.

- 1969

- Introduction. In Ethnic Groups and Boundaries: The Social Organization of Culture Differences. Little, Brown and Company, Boston.

- 1994

- Enduring and Emerging Issues in the Analysis of Ethnicity. In The Anthropology of Ethnicity: Beyond 'Ethnic Groups and Boundaries,' edited by Hans Vermeulen and Cora Govers, pp. 11-32. Het Spinhuis, Amsterdam, Denmark. 9

- 1995

- Cultural Dimensions of Ethnicity in the Archaeological Record. Keynote address, 28th Annual Meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C.

- 1993

- Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives. Pluto Press, Boulder, Colorado.

- 1980

- The West Coast Chinese and Opium Smoking. In Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America: Afro-American and Asian American Culture History, edited by Robert L. Schuyler, pp. 97-101. Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., Farmingdale, New York.

- 1975

- Ethnicity: Theory and Experience. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- 1996

- Introduction. In Ethnicity, edited by John Hutchinson and Anthony D. Smith, pp. 3-14. Oxford University Press, New York.

- 1997

- The Archaeology of Ethnicity: Constructing Identities in the Past and Present. Routledge, New York.

- 1984

- Kingsmill Plantations, 1619-1800: Archaeology of Country Life in Colonial Virginia. Academic Press, Orlando.

- 1976

- Towards a New Formulation of the Concept of Ethnic Group. Ethnicity 3:202-213.

- 1987

- Aspects of Early Afro-American Material Culture: Artifacts from the Slave Quarters at Garrison Plantation, Maryland. Historical Archaeology 21(2):112-119.

- 1982

- The Study of Ethnicity in Historical Archaeology. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 1:159-178.

- 1983

- Ethnic Group, Status and Material Culture at the Rancho Punta de Agua. In Forgotten Places and Things: Archaeological Perspectives on American History, edited by Albert E. Ward, pp. 193-203. Center for Anthropological Studies, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

- 1987

- Delineating Ethnicity from the Garbage of Early Virginians: Faunal Remains from the Kingsmill Plantation Slave Quarter. American Archaeology 6(1):31-39.

- 1992

- The Cowrie Shell in Virginia: A Critical Evaluation of Potential Archaeological Significance. Master's thesis, Department of Anthropology, The College of William & Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1988

- What Happened to the Silent Majority?: Research Strategies for Studying Dominant Group Material Culture in Late Nineteenth-Century California. In Documentary Archaeology in the New World, edited by Mary C. Beaudry, pp. 192-202. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 10

- 1980

- Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America: Afro-American and Asian American Culture History. Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., Farmingdale, New York.

- 1980

- Preface. In Archaeological Perspectives on Ethnicity in America: Afro-American and Asian American Culture History, edited by Robert L. Schuyler, pp. vii-viii. Baywood Publishing Company, Inc., Farmingdale, New York.

- 1989

- Introduction: Archaeological Approaches to Cultural Identity. In Archaeological Approaches to Cultural Identity, edited by Stephen J. Shennan, pp. 1-32. Routledge, New York.

- 1996

- Foreword: Theories of American Ethnicity. In Theories of Ethnicity: A Classical Reader, edited by Werner Sollors, pp. x-xliv. New York University Press, Washington Square, New York.

- 1990

- Studies in Ethnicity in North American Historical Archaeology. North American Archaeologist 11(2):121-145.

- 1996

- Blue Beads as African-American Cultural Symbols. Historical Archaeology 30(3):49-75.

- 1980

- Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Belknap Press of Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

- 1996

- Ethnicity, Authenticity, and Invented Traditions. Historical Archaeology 30(2):1-7.

- 1994

- Ethnicity, Nationalism, and State-making: Ethnic Groups and Boundaries, Past and Future. In The Anthropology of Ethnicity: Beyond 'Ethnic Groups and Boundaries,' edited by Hans Vermeulen and Cora Govers, pp. 33-58. Het Spinhuis, Amsterdam, Denmark.

- 1989

- A Class Act: Anthropology and the Race to Nation Across Ethnic Terrain. Annual Reviews in Anthropology 18:401-444.

- 1992

- Of Straightening Combs, Sodium Hydroxide, and Potassium Hydroxide in Archaeological and Cultural-Anthropological Analyses of Ethnogenesis. American Antiquity 57(4):608-612.

Industrial Transition and the Rise of a "Creole" Society in the Chesapeake, 1660-1725

John Metz

The first century of settlement in Virginia is best characterized as a period of great social, political, and economic experimentation that ultimately resulted in the development of a distinctive colonial society (Greene 1988; Horn 1994; McCusker and Menard 1991; Shammas 1979). Tobacco became the mainstay of Virginia's economy early in the seventeenth century virtually to the exclusion of all other economic pursuits. The cultivation of tobacco for export, clearing land for more tobacco, and raising corn and livestock for subsistence dominated the lives of colonists in the Chesapeake (Carr and Walsh 1988; Main 1982). By the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, the pattern had changed dramatically. Corn and wheat were grown for export, craft specialization and household manufacture were on the rise, and slaves had nearly replaced indentured servants in the labor force (Galenson 1981; Morgan 1975). The society that developed in the Chesapeake was so unique that British officials often made explicit distinctions between the English-born and the "natives" or "creoles" born in Virginia. A trend developed where native-born whites were increasingly singled out by English writers as "natives," "Virginians," and "creoles" as they achieved dominance in a colonial government previously controlled by English-born immigrants (Shammas 1979).

The term creole is a word born of the European colonial experience. It is derived from the Spanish word criollo, meaning native to the locality. The first use of the word is in a Spanish chronicle written in 1604 which refers to those born in the colonies of Spanish parents as criollos (Oxford English Dictionary 1971(I):1163). Criollo was quickly incorporated into the English language where it was Anglicized to creole by the late seventeenth century. Like the Spanish, the English used the term to distinguish its colonial-born citizens from those born in the homeland. The need to differentiate between colonial and English-born was based on the perception that the exposure to new climates, cultures, and surroundings influenced socio-cultural modifications within colonial society (Shammas 1979:284-286).

Just as the English began to identify the citizens born in the colonies as "creoles," the identity of any group depends upon how others perceive that group and how the members of the group, in turn, see themselves. This affiliation becomes "ethnic" when "it classifies a person in terms of his basic, most general identity, presumptively determined by his origin or his background" (Barth 1969:13). This identity often poses a threat to dominant groups in society and results in some form of discrimination, whether it be prohibited access to resources or outright exclusion from mainstream society. In the 1980s, Randall McGuire explored group formation and boundary maintenance among ethnic groups. He argued that "competition provides motivation for group formation, ethnocentrism channels it along ethnic lines, and the differential distribution of power determines the nature of the relationship" (McGuire 1982:160). These three variables are usually focused in the political or economic arenas of society. This model is applicable to the relationship between England and her colony in Virginia, especially after the political and economic aims of the Crown and of 12 the colonists had begun to diverge from one another.

"Creole consciousness" developed in the 1680s as native-born politicians began to replace their English-born predecessors in the colonial government. The English-born leaders were part of a second generation of colonists who arrived in the 1630s and 1640s. Many came with money, while others were minor gentry who maintained their ties with England even as they pursued wealth through the sale of tobacco and land speculation (Bailyn 1959:91). Although native-born colonials lacked the English connections of their forebears, they worked to achieve their goals by developing vital social, political, and economic institutions within the colony. As a result, the agendas of native leaders often ran counter to homeland interests. In 1693, for example, Governor Nicholson complained to the Board of Trade that "the country consists now mostly of Natives, few of which either have read much or been abroad in the world, so that they cannot form to themselves any Idea or Notion of these things." However, in terms of trade and economy he added simply that "they are knowing" (Nicholson 1692/1693 in Shammas 1979:286).

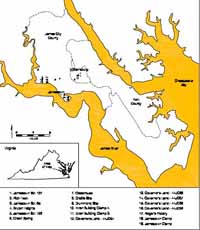

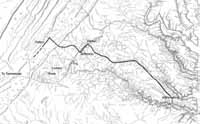

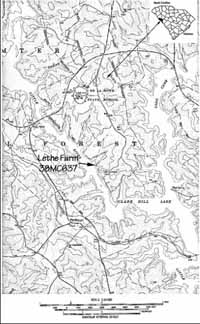

The tobacco culture that took hold of the economy beginning in the second quarter of the seventeenth century inspired colonists to amass land and focus all of their labor and capital on the cultivation of tobacco for the export market. At first, profits were high enough to discourage the development of local manufactures. Artisans who immigrated to Virginia during this period often abandoned their trades to enter the more lucrative tobacco market (Galenson 1981:127; Morgan 1975:140-141). As a result, a pattern of dependency developed where planters grew tobacco for export in return for finished goods from England. Total reliance on an outside market stagnated Virginia's economy. Anthony Langston painted a dire picture of the colony in 1657 when he wrote "wee suffer for want of Markets, Trades, and Manufactures" (Langston 1921:103). While colonial leaders continually worked to promote economic diversification, their efforts met with failure until prolonged slumps in the tobacco market gave local industry the push it needed to become a permanent element of the economy. A survey of seventeenth-century industrial sites identified in York County, James City County, and the City of Williamsburg in the Virginia Tidewater documents the diversification of the economy, an increase in craft specialization, and the emergence of new patterns of local exchange between 1660 and 1725 (Figure 1). An archaeological consideration of these sites reveals an increase in local manufactures associated with the trend towards greater self-sufficiency.

Industrial Development in Seventeenth-Century Virginia

Virginia was initially settled by the Virginia Company of London as a speculative venture designed to furnish England with staple commodities and provide dividends for investors. The Virginia Company envisioned a mixed economy of commerce, manufacturing, and farming. Virginia offered a seemingly endless supply of resources like lumber and hides which the English were formerly "enforced to buy, and receive at the curtesie of other Princes" (Billings 1975:15). The first settlers also explored the commercial viability of a wide range of crops and industries. Glass, silk, pitch, tar, and soap ash were tried with mixed success (Billings 1975:7-9; Middleton 1992:25). Likewise, many varieties of seeds were planted to test their efficacy. In 1612, John Rolfe began testing a new variety of tobacco from the West Indies

in an effort to improve upon the bitter, North

13

Figure 1. James City County, York County, and the City of Williamsburg. Map by the author and Heather

Harvey.

American leaf that Sir Francis Drake had introduced to England in 1586 (Billings 1975:175-176; Middleton 1992:28-29). After two years of experimentation, John Rolfe shipped four hogsheads of the West Indian strain of tobacco to London, touching off a craze that would shape the direction of the colony over the next century and a half.

Figure 1. James City County, York County, and the City of Williamsburg. Map by the author and Heather

Harvey.

American leaf that Sir Francis Drake had introduced to England in 1586 (Billings 1975:175-176; Middleton 1992:28-29). After two years of experimentation, John Rolfe shipped four hogsheads of the West Indian strain of tobacco to London, touching off a craze that would shape the direction of the colony over the next century and a half.

Despite the insatiable demand for tobacco after 1614, Virginia remained little more than a struggling military outpost. In 1618, the Virginia Company attempted to reorganize the colony under the Charter of 1618 which established four municipalities to serve as "focal points" for the Virginia colony (Craven 1970:129). James City, Charles City, Henrico, and Kecoughtan (later Elizabeth City) were incorporated to promote trade and commerce and provide settlers protection from Indian attack. The municipalities each consisted of 3000 acres worked by the company's tenants at half shares to pay salaries of colonial officers. An extra 3000 acres were set aside in James City County for the Governor's salary (Craven 1970:130). Likewise, 100 acres of glebe land were also set aside to provide the salary for a minister. The charter even included a provision offering 14 four acres of land in a town for a nominal rent of four pence per year to craftsmen as an inducement to immigrate (Craven 1970:130). In 1619, colonial officials initiated shipbuilding, glassmaking, and ironworking ventures, yet each failed within a few years (Horning 1995:135-136).

Efforts to promote the development of other industries and commodities continued after the demise of the Virginia Company in 1624. John Harvey, who served as governor between 1630 and 1635, and again between 1637 and 1639, attempted to create a thriving economic center in Virginia by promoting an act making Jamestown the sole port of entry for the colony (Horning 1995:146). The Crown bristled at this attempt to control trade and promptly called on Virginia's government to revoke the legislation. Although the colonial officials refused, the Crown's lack of support made it difficult to enforce the Act, thereby rendering it ineffective (Horning 1995:147-149; Middleton 1992:43).

Harvey also worked to promote economic development by privately funding industrial ventures in the 1630s. He established an industrial compound consisting of several different crafts on property he owned located near the middle of New Towne on Jamestown Island (Horning 1995:169). Two rectangular kilns (Structures 111-A and 111B) and a circular pit possibly used as an iron bloomery (Structure 111-C) represent the first crafts to be established in this area (Cotter 1958:110-111). While the exact function of the kilns remains unclear, burned oyster shell discovered on the floors of both kilns suggests that they were used at least once to slake lime. The pit used for smelting iron was dug into one of the adjacent kilns (Structure 111B). This bloomery consists of a circular pit measuring ten feet in diameter by one foot in depth where bog iron was smelted to produce bar iron (Cotter 1958:110). A large, brick structure (Structure 110) discovered twenty feet east of the kilns and the bloomery appears to have been another component of Harvey's industrial enclave. Analysis of this structure and the recovered assemblage suggests it functioned as a brewhouse and an apothecary (Cotter 1958:102-109; Horning 1995:169). Enthusiasm was not enough to spark industry at Jamestown, however. Despite Harvey's efforts, all of these ventures disappeared by mid-century.

Efforts to diversify Virginia's economy continued to fail throughout the first half of the seventeenth century precisely because tobacco was so profitable. The lucrative tobacco market encouraged planters to concentrate on a single commodity for the export market while virtually all goods and services were purchased from abroad. Planters even continued to turn a profit in the 1630s when tobacco prices tumbled nearly 90 percent from three shillings to three pence a pound (Middleton 1992:42). The conditions necessary to promote diversification were absent in the Chesapeake until after 1660. By this time, declining profits and a limited market necessitated the development of a local economy and alternative economic ventures appeared more attractive relative to tobacco.

Virginia's social and economic climate was in the midst of change early in the 1660s when William Berkeley returned to serve as governor of the colony for a second time following the death of Oliver Cromwell and the restoration of the monarchy. By the time Berkeley arrived in Virginia, England passed the first of the Navigation Acts declaring exclusive rights over Virginia's market. While these acts benefited English merchants, they did so at the expense of the colonial economy. The acts, declared "mighty and destructive" by Governor Berkeley, constricted the slumping tobacco market and prohibited cheaper Dutch goods and services (Middleton 1992:113). The volatile cycle of boom and bust that resulted made it impossible for planters 15 to rely solely on tobacco as they had in the past. Continued instability in the tobacco market prompted farmers to diversify their agricultural strategies to include corn and grain and engage in animal husbandry on a larger scale (Carr and Walsh 1988:145-146). A more diverse planting regimen diminished the reliance on English markets by allowing planters to exchange surplus produce and meat for locally available goods and services. Moreover, increased exchange encouraged the development of a host of crafts to meet the demand for services and finished goods. Ultimately, alternative sources of income, or "import replacement activities," resulted in the growth of a "complex network of local interdependence" that helped buffer Chesapeake planters against fluctuations in crop prices (Carr and Walsh 1988:145-146).

Occupational data from York County, Virginia (Table 1) reflects an increase in the number and variety of trades corresponding to agricultural diversification during the second half of the seventeenth century. The York County records are unique for their volume and consistent coverage from the 1630s through the eighteenth century. Historians with the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation compiled a database representing a 10 percent sample of the York County records providing scholars with a valuable research tool. A total of twenty-one trades are represented in the York County records database for the period between 1640 and 1740 (Table 1). Between 1640 and 1669, sixteen individuals identified were engaged in seven trades, including a sawyer, a builder, an ordinary keeper, two planters, two coopers, two gunpowder makers, and seven carpenters (York County Records [hereafter YCR]). With the exception of the ordinary keeper and the gunpowder makers, all of the individuals represented during this period were involved in trades associated with growing tobacco or preparing it for export. Planters grew tobacco, sawyers cut the wood needed for barrels and buildings, coopers made the hogsheads that would carry tobacco to England, while builders and carpenters constructed houses and tobacco barns.

Ten trades are represented in the sample between 1670 and 1699 (YCR). While a majority (75%) of the 43 York County residents counted were involved in tobacco-related occupations during this period, the number of trades not associated with tobacco cultivation increased from two to five. Ordinary keepers (two) and gunpowder makers (three) continued to be represented between 1670 and 1699, while new occupations included a brickmaker, a joiner, and a millwright (YCR). While carpenters, sawyers, coopers, and gunpowder makers were still present, the appearance of a joiner suggests that finished goods that could only be obtained from abroad earlier in the century were being produced in York County after 1690. Likewise, the presence of brickmakers and millwrights may indicate that more services were available locally. Moreover, the appearance of a millwright in 1698 suggests that planters were growing enough corn and grain to support a local mill.

The trend towards greater diversification continues after 1700 when the number of craft-related trades represented in the York County record database outnumber those associated with tobacco and agriculture for the first time (YCR). Over half (57%) of the 44 individuals identified in the records between 1700 and 1729 were artisans as compared to only 11 artisans out of 43 (25%) recorded between 1670 and 1699. Twelve trades were identified for the period between 1700 and 1729, including six trades which are represented for the first time in the York County. The occupations which appear in the records after 1700 are all craft-related, including an armorer, a brazier, ten bricklayers, three glaziers, a silversmith, a clock/watchmaker, and 16

| Trade | 1640 | 1650 | 1660 | 1670 | 1680 | 1690 | 1700 | 1710 | 1720 | 1730 | 1740 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armorer | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 |

| Brazier | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Brickmaker | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | 2 | 3 |

| Bricklayer | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3 | 3 | 4 | — | — | 10 |

| Builder | — | 1 | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 3 |

| Carpenter | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 45 |

| Cooper | — | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | — | 1 | — | — | — | 9 |

| Cutler | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Founder | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 |

| Glazier | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 2 | — | — | 3 |

| Gunpowder maker | — | 2 | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | 6 |

| Gunsmith | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | 1 |

| Joiner | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| Millwright | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 1 |

| Ordinary keeper | — | 1 | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 3 |

| Painter | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 |

| Planter | — | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | — | — | — | — | — | 7 |

| Sawyer | — | 1 | — | — | — | 2 | — | — | — | — | — | 3 |

| Silversmith | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | 2 | 3 |

| Clock/watchmaker | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | 2 | — | 3 |

| Whitesmith | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 1 | — | — | 1 |

| Total by Decade | 2 | 10 | 4 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 21 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 13 | 116 |

The Archaeology of Seventeenth-Century Industrial Sites

The growth of local Chesapeake industry is also reflected in the archaeological record. In

Virginia, nineteen industrial sites dating between 1640 and 1725 have been identified in York County, James City County, and the City of Williamsburg (Figure 2). Fourteen of the sites are located in James City County, reflecting the sustained research on Jamestown Island as well as archaeology conducted as part of development along the James River. Four industrial sites were identified in the City of Williamsburg while only one has been found in York County. The sites include a glass furnace, the remains of a bloomery, three potteries, and fourteen brick-producing sites (Table 2). With the exception of a brick kiln

17

Figure 2. Location of industrial sites in James City County, York County, and the City of Williamsburg. Map by the author and Heather Harvey.

(Structure 127) located on Jamestown Island, all of the industrial sites postdate 1660.

Figure 2. Location of industrial sites in James City County, York County, and the City of Williamsburg. Map by the author and Heather Harvey.

(Structure 127) located on Jamestown Island, all of the industrial sites postdate 1660.

The excavation of the Drummond site in James City County produced evidence of a primitive bloomery operation dating to the 1680s (Outlaw 1975a). The evidence is unusual given the fact that large-scale bloomeries and foundries were not established in Virginia until the 1720s (Harvey 1988). William Drummond was a gentleman planter who leased land on the 2000-acre Governor's Land tract. Although Drummond was executed in 1676 for joining Nathaniel Bacon in an attempt to overthrow the colonial government under William Berkeley, his family and servants remained on 18

| Site | Site Type | Date | Location | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jamestown Str. 127 | Brick/tile kiln | Ca.1650 | JCC | Cotter 1958 | |

| Rich Neck | Brick/tile kiln | Ca.1660 | Wmsbg | Metz 1994 | |

| Jamestown Str. 65 | Brick/tile kiln | Ca.1660-1675 | JCC | Cotter 1958 | |

| Bruton Heights | Brick/tile kiln | Ca.1662 | Wmsbg Metz et al. | 1996 | |

| Jamestown Str. 102 | Brick/tile kiln | Ca.1662 | JCC | Cotter 1958 | |

| Green Spring | Pottery | Ca.1665-1680 | JCC | Caywood 1955; Smith 1980 | |

| Glasshouse | Glasshouse | Ca. 1666 | JCC | Carson 1954 | |

| Challis Site | Pottery | Ca.1680-1725 | JCC | Noël Hume 1963; Pittman 1995 | |

| Drummond Site | Bloomery/tobacco pipe manufactory | Ca.1680-1730 | JCC | Outlaw 1975b | |

| Wren Building Clamp A | Brick clamp | 1695 | Wmsbg | Dearstyne 1951 | |

| Wren Building Clamp B | Brick clamp | 1695 | Wmsbg | Dearstyne 1951 | |

| Governor's Land—44JC84 | Brick clamp | Ca.1700-1725 | JCC | Outlaw 1975a | |

| Governor's Land—44JC86 | Brick clamp | Ca.1700-1725 | JCC | Outlaw 1975a | |

| Governor's Land—44JC87 | Brick clamp | Ca.1700-1725 | JCC | Outlaw 1975a | |

| Governor's Land—44JC89 | Brick clamp | Ca.1700-1725 | JCC | Outlaw 1975a | |

| Governor's Land—44JC99 | Brick clamp | Ca.1700-1725 | JCC | Outlaw 1975a | |

| Rogers Pottery | Pottery | Ca.1711-1740s | York Co. | Barka 1973; Barka et al. 1984 | |

| Jamestown Clamp Brick clamp | 1720s? JCC | Horning and Edwards | 1988 | ||

| Jamestown Clamp | Brick clamp | 1720s? | JCC | Horning and Edwards | 1998 |

Archaeological evidence indicates that William Berkeley established a glasshouse and a pottery on his Green Spring Plantation in James City County. Berkeley acquired the Green Spring property in 1641 and lived there until his death in 1677 (Caywood 1955:3). Always working to promote new industries in the Virginia colony, he raised tobacco, rice, and flax, experimented with silk, made wine, and harvested timber for export. A small glass furnace was identified east of Berkeley's residence on Powhatan Creek during the first archaeological investigation of the plantation in 1928. The furnace was reported to be of brick construction, and included a brick marked "Aug., 1666" (Carson 1954:12). Although little is known about this site, it very well may have been part of Berkeley's efforts 19 to encourage the development of colonial industry.

The pottery at Green Spring Plantation was identified near the house during archaeological investigation of the site conducted in the early 1950s. Descriptions and photographs indicate that the kiln was a rectangular updraft-type kiln with a firebox beneath a firing chamber (Caywood 1955:1213). Excavation of the kiln produced utilitarian earthenwares in a variety of forms including lead-glazed and bisque vessels, flat roofing tiles, and pan tiles (Caywood 1955:13; Smith 1980:63). Datable artifacts excavated from the kiln indicates that the site was active between 1665 and 1680. The paucity of Green Spring pottery on other sites in the region suggests that either the manufactory was short-lived or that it produced items for use on Green Spring Plantation (Smith 1980:96).

Other potteries in the region include the Challis site in James City County and the William Rogers Pottery in Yorktown. Ivor Noël Hume excavated the Challis site in the 1960s. Although a kiln was never identified, the salvage excavation of a large pit eroding out of the bank into the Chickahominy River produced enough waster material to suggest a ceramic production site that began sometime around 1680 and remained in operation until 1730 (William Pittman, personal communication, 1995). Products from the site consist primarily of lead-glazed and bisque utilitarian earthenwares. Like the ceramics produced on Green Spring Plantation, pottery from the Challis site does not appear on many sites, suggesting that it was for use on a single plantation or for very limited distribution.

The William Rogers pottery, on the other hand, was a far more ambitious undertaking. Although the name of William Rogers is historically linked to the site, he appears to have been an entrepreneur who funded the pottery and may not have been involved in the actual production of ceramics (Barka 1973, 1984). The pottery might have been in operation as early as 1711 when Rogers purchased the property, although a dated cup buried ceremoniously behind the kiln indicates that it was started in 1720. An archaeological investigation of the site conducted in the early 1970s revealed a sophisticated kiln as well as the remains of an associated factory building. The distribution of material across the site suggests that this production site may have included additional structures and possibly another kiln located on privately-owned property adjacent to the kiln site (Barka et al. 1984). Production continued into the 1740s and included a range of distribution that spanned the Chesapeake (Barka 1984; Pittman, personal communication, 1995). Despite the archaeological evidence for a successful pottery, Governor William Gooch referred to the artisan as the "poor potter" of Yorktown in a report on manufactures to the English Board of Trade in 1730 (Gooch in Barka 1973:292). Norman Barka suggests that this dismissive reference reflected the royal governor's sympathy for local industrial development at a time when English officials were trying to keep colonial trades from competing with homeland industries (Barka 1973:292).

While an increase in the number and variety of industrial sites in the Virginia Tidewater indicates growing economic diversity, the archaeological record suggests that the technology employed in some crafts may have changed within the context of a plantation economy. The development of Chesapeake brickmaking in particular reflects both the technological shifts that appear to correlate with the trend towards greater economic diversification and increased self-sufficiency on farms, as well as the transition from indentured servitude to slave labor. Brick kilns are often the most common type of industrial 20 feature found on seventeenth and early eighteenth-century sites. To date, fourteen brick kilns dating between 1650 and 1729 have been identified in James City County, York County, and the City of Williamsburg.

The archaeological remains of brickmaking appear to be so common because of their role in the building industry. Indeed, after the Great Fire of London in 1666, contractor and land speculator Nicholas Barbon declared building to be the "chiefest promoter of trade [because] it employs a greater number of trades and people than feeding and clothing, [including] those that make materials for building, such as brick, lime, tile, etc." (Barbon in Sella 1977:372) . Despite the prevalence of earthfast or post-in-ground construction in Virginia during the seventeenth century, bricks were commonly used to construct hearths and foundations, as well as to line cellars. As demand for bricks increased over the seventeenth century, it was more cost effective to burn the bricks needed for the project on the construction site. In Bedfordshire, England, during the early nineteenth century, for example, the price of 1000 bricks increased two percent for every mile they were shipped, while the cost increased 45% for every mile beyond a five mile radius of the brickyard (Cox 1979:11). The cost of transporting brick in colonial Virginia must have been prohibitive given the sprawling nature of settlement.

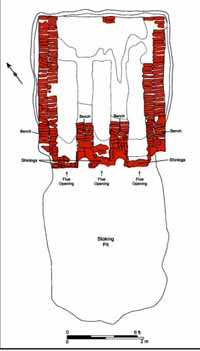

Bricks were fired in "clamps" and "kilns" throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The construction and preparation of clamps and kilns for firing varied little over time. The brickmaker and his crew stacked green bricks in rows called benches two or three bricks wide. A space measuring a finger's width was left between each brick to allow for the circulation of heat throughout the kiln. Benches alternated with channels or flues which held the wood fuel. Benches were stacked five or six courses high before bricks were staggered in towards the channels to create corbelled arches. Kilns were typically stacked to a height of 14 or 15 feet (Barka 1984:271). An average-sized kiln could hold between 3000 and 5000 bricks per channel, or a total of 20,000 to 30,000 bricks per kiln (Dobson 1971(I):141; Goldthwaite 1980:179). The structure of green bricks was encased in a shell of fired bricks and plastered over with mud to insulate the kiln. A plug of green brick called a shinlog was placed at the openings of the flues and allowed the brickmaker to control the intensity and distribution of the heat within the kiln by raising or lowering the shinlogs over the eyes of the channels.

The difference between clamps and kilns lies in the permanence of the structures. Edward Dobson, an expert on the industry in the early nineteenth century, defined a clamp as "a pile of bricks arranged for burning in the ordinary way, and covered with a temporary casing of burnt brick to retain heat" (Dobson 1971(I):38). Quite simply, "clamps" were temporary kilns constructed of the material they were producing. Once firing was complete, the clamp was dismantled, leaving only a footprint of burned soil and perhaps a few brick wasters. Clamps were generally built on a construction site to provide brick for a single project. Itinerant brickmakers often fired brick in clamps because they required less labor and expense to construct and burn than larger, more permanent kilns (Cox 1979:11). The major drawback of this kiln type was the inability to control the firing process. Unlike the more permanent structures, the heat could not be redistributed to other areas of the kiln. Consequently, clamp-fired material included a greater percentage of under- and over-burned wasters. Analysis of the brick making industry in Europe has shown that 21 clamps remained popular in areas where fuel was cheap despite their inefficiency (Goldthwaite 1980:186-187).

Kilns, on the other hand, were permanent or semi-permanent structures built of brick or stone and consisted of a distinct firebox and stoking pit (Figure 3). Dobson defined a kiln as "a chamber in which the bricks are loosely stacked, with spaces between them for the passage of heat" (Dobson 1971(I):38). A common kiln type consisted of a walled chamber above vaulted firing chambers, similar to the "Roman pit-type kiln" (Goldthwaite 1980:178). Kilns were often lined with highly refractable material such as under-fired brick for use on brickyards or for extremely large projects involving many firings. Unlined pit-type kilns considered to be semi-permanent were built to provide brick and tile for large projects or specialty items (Eams 1961:167). Burning times were also shorter with the permanent and semipermanent updraft kilns due to heavier construction and increased insulation which resulted from burying the firebox (Barka 1984:192). Better insulation also allowed kilns to achieve higher firing temperatures than clamps.

Five substantially constructed rectangular updraft kilns have been identified within a five-mile radius of Williamsburg. Three of these have been excavated, including one at Bruton Heights and two at Jamestown. Another exposed on Jamestown Island was partially excavated in the 1950s (Cotter 1958:8081). The remains of a fifth kiln recently identified at the Rich Neck Plantation site in Williamsburg appears to match this configuration as well (Metz 1994). All of the local kilns date to a period between 1640 and 1675.

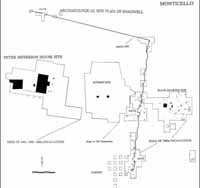

The brickyard on the Bruton Heights school property represents the most intact brick manufactory of the period (Metz 1995; Metz et al. 1997:51-67). John Page acquired the Bruton Heights property in 1655, five years after he arrived in the colony. Like many immigrants who arrived in Virginia during the 1640s and 1650s, Page was an educated man from a prosperous English family (Metz et al. 1997:43). These qualities allowed him to move freely in the upper strata of Virginia society and politics. Page was elected to the House of Burgesses by 1655, and became Sheriff of York County and the head of the county militia in the 1670s. His political career culminated in 1680 with an appointment to Virginia's Council of State. John Page swore out patents to over 7000 acres of land in southeastern Virginia and owned several plantations (Bruce 1935:253). His Middle Plantation holdings included much of what was to become the City of Williamsburg in 1699.

The archaeological evidence from the site includes an irrigation ditch, three clay tempering areas, several pugmills and water barrel stations for mixing, and an earthfast structure, probably used as a molding or drying shed, all symmetrically organized around a

single kiln (Figure 4). The symmetrical placement of the activity areas reflects the different stations involved in the brick and tilemaking process. A carved brick cartouche bearing Page's initials and the date 1662 (when the construction of his manor house was likely completed) indicates that the brickyard was active during the early 1660s. Judging from the elaborate kiln and complex brickyard, Page commissioned an English-trained brickmaker for the construction of a manor house, a large brick dependency and, perhaps, several other brick structures at Middle Plantation. The Bruton Heights kiln measured 12 x 11.5 feet and was excavated to a depth of three feet (Metz et al. 1997:5759). Three channels extended to the rear wall of the kiln. Although a kiln with three "eyes," or openings, would have had four benches, only portions of the two outermost benches survived in the Bruton Heights kiln. The

22

Figure 3. Plan of the Page kiln at Bruton Heights. Drawing by Kimberly Wagner and Heather Harvey.

23

Figure 3. Plan of the Page kiln at Bruton Heights. Drawing by Kimberly Wagner and Heather Harvey.

23

Figure 4. Plan of Page brickyard at Bruton Heights (map by Kimberly Wagner and Heather Harvey).

walls and the floor were unlined, indicating that the kiln was of the semi-permanent type

with an estimated life-span of three to four years (Cherry 1991:192; Eams 1961:167). The firebox is unlined, suggesting it was semipermanent, while artifacts recovered from the site indicate that flat roofing tile, molded and carved brick, and pavers were produced at the site (Metz et al. 1997:63-67).

Figure 4. Plan of Page brickyard at Bruton Heights (map by Kimberly Wagner and Heather Harvey).

walls and the floor were unlined, indicating that the kiln was of the semi-permanent type

with an estimated life-span of three to four years (Cherry 1991:192; Eams 1961:167). The firebox is unlined, suggesting it was semipermanent, while artifacts recovered from the site indicate that flat roofing tile, molded and carved brick, and pavers were produced at the site (Metz et al. 1997:63-67).

The other rectangular updraft kilns are similar to the example at Bruton Heights in both form and product. Structure 127 at Jamestown consisted of a subterranean firebox measuring 11 x 9 feet, and excavated to a depth of five and a half feet (Cotter 1958:145). Three benches measuring two bricks wide and two channels were identified within the firebox. The firebox was unlined, indicating that it was for a short-term project. Although John Cotter describes Structure 127 as a "probable first-quarter 17th-century enterprise," based on the domestic tobacco pipe stem fragments found in the kiln fill, it is more likely that this kiln operated some time around the 1650s based on its location in "New Towne," as well as from our current understanding of domestic pipes and their temporal affiliation (Cotter 1958:145-147; Emerson 1994; Mouer 1993:124-146).

Structure 102 is a massive, brick-lined kiln which measures 19 x 25 feet (Cotter 1958:96-98; Harrington 1950:23). Excavation revealed a large, brick-lined firebox with the remains of five channels and six benches. 24 Benches were three bricks wide and stacked in a herringbone pattern to facilitate heat distribution throughout the kiln. Presence of a replaceable brick lining indicates that Structure 102 was a permanent kiln. Artifacts recovered from Structure 102 suggest that the kiln was built to produce brick and roofing tile for several structures or a public building project. J.C. Harrington speculates that Structure 102 must pre-date 1683 because a land patent signed by Nathaniel Bacon in that year makes no mention of a kiln (Harrington 1950:28). Likewise, subsequent property deeds for the area surrounding the kiln are silent on the matter. The size of this kiln suggests it may have been built in response to the Cohabitation Act of 1662 which called for the construction of thirty brick buildings at Jamestown (Cotter 1958:96-98; Harrington 1950:23).

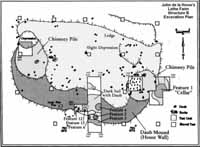

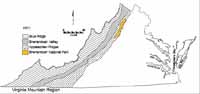

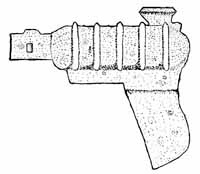

Although Structure 65 on Jamestown Island was identified as a brick kiln by archaeologist H. Summerfield Day in 1935, it was never completely excavated (Cotter 1958:7477,80-81). Judging from the limited data that exists, this kiln consists of a subterranean firebox and stoking pit. Archaeologists determined that Structure 65 produced brick and roofing tile for Structure 31, "a substantial foundation of a brick house" (Cotter 1958:77). Given the location of Structures 31 and 65 on the "Sherwood Tract," Cotter speculates that the structure and the kiln may have belonged to William Sherwood, whose house was recorded on the Ambler Plat dated 1680 (Cotter 1958:74-77). As such, Structure 65 appears to date to the third quarter of the seventeenth century.