Williamsburg Cultural Resources Map Project

City of Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0381

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2009

Williamsburg Cultural Resources Map Project

City of Williamsburg

Department of Archaeological Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

PO Box C

Williamsburg, Virginia 23187

Marley R. Brown III

Principal Investigator

March 1996

Re-issued

November 2001

| Page | |

| Research Strategy | 1 |

| Cultural Resource Sensitivity Mapping | 1 |

| Data Limitations | 2 |

| Prehistoric Site Potential | 2 |

| Historic Site Potential | 2 |

| Early Settlement of Middle Plantation | 2 |

| The Establishment of Williamsburg | 10 |

| Williamsburg, An Urban Center | 13 |

| The Revolutionary War and Relocation of the Captial | 16 |

| The Early National Period | 16 |

| The Civil War | 21 |

| Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917) | 25 |

| The Modern Era | 27 |

| Annexation and Growth | 34 |

| References Cited | 39 |

| Appendix 1. Historic Resources Omitted by Cartographers | 42 |

| Appendix 2. Williamsburg's Colonial Roads | 43 |

| Appendix 3. Williamsburg-James City County Plats | 44 |

| Appendix 4. York County Plats | 47 |

| Appendix 5. Historical Maps Used in Electronic Mapping | 48 |

| Page | |

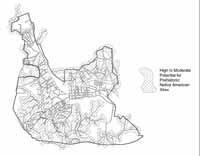

| 1.Prehistoric sensitivity map | 3 |

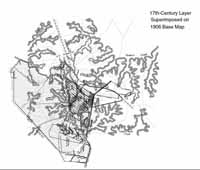

| 2.Seventeenth-century layer superimposed on 1906 base map | 5 |

| 3.Richard Kemp 1642 survey with Philip Ludwell's 1678 survey superimposed | 7 |

| 4.Middle Plantation features shown in relation to CW street plan | 8 |

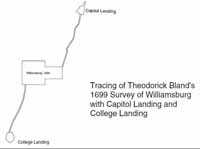

| 5.Tracing of Theodorick Bland's 1699 survey of Williamsburg with Capitol Landing and College Landing | 11 |

| 6.Matthew Davenport's 1774 survey of Princess Anne Port (College Landing) | 12 |

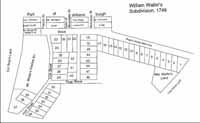

| 7.William Waller's subdivision, 1749 | 14 |

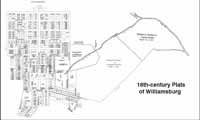

| 8.18th-century plats of Williamsburg | 15 |

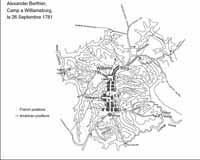

| 9.Alexander Berthier, Camp a Williamsburg, le 26th Septembre 1781 | 17 |

| 10.The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg,1782 | 18 |

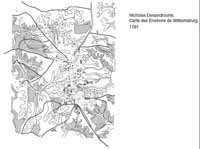

| 11.Nicholas Desandrouins, Carte des Environs de Williamsburg, 1781 | 19 |

| 12.18th-century layer | 20 |

| 13.Sketch of Battlefield and Confederate Works in Front of Williamsburg, VA, May 8th, 1862, by Lieut. McAlester | 22 |

| 14.Map showing the position of Williamsburg, by Capt. John Hope,1862 | 23 |

| 15.Vicinity of Williamsburg and Yorktown, Anonymous 1871 | 24 |

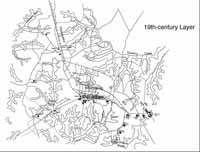

| 16.19th-century layer | 26 |

| 17.Sanborn insurance map, 1904 | 28 |

| 18.Sanborn insurance map, 1910 | 29 |

| 19.Sanborn insurance map, 1921 | 30 |

| 20.Sanborn insurance map, 1933 | 31 |

| 21.Sanborn insurance map, 1939 | 32 |

| 22.Williamsburg map, 1931 | 35 |

| 23.Williamsburg map, 1941 | 36 |

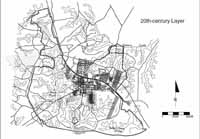

| 24.20th-century layer | 37 |

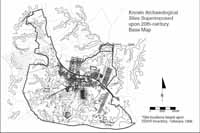

| 25.Known archaeological sites superimposed on 20th-century base map | 39 |

Research Strategy

Documentary research commenced with the identification of cartographic resources potentially useful in delineating areas of cultural sensitivity. Historic map facsimiles were examined at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, the Virginia Historical Society, the Library of Virginia, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, the National Archives, the Library of Congress, the College of William and Mary's Department of Special Collections, and the Corps of Engineers Archives at Fort Norfolk. Maps and plats on file at the Williamsburg-James City County and York County courthouses were used to document the city's development and to identify culturally sensitive areas within territory added to the City of Williamsburg through annexation. The Sanborn Insurance Company's maps of Williamsburg (1904-1930) were reviewed, as were sketches appended to Mutual Assurance Society policies. A broad but carefully selected group of historic maps were collected for digitization and compilation into temporally structured layers.

Use was made of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's base map upon which are identified archaeological sites within the historic area. Up-to-date archaeological site survey data were procured from the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's York County Project Tract Map and records of the Virginia Land Office (land patents) were examined as a means of identifying land ownership patterns and cultural features within Middle Plantation and its successor, Williamsburg. Use was made of the Resource Protection Process planning document (RP3) and management plan, reports prepared by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation personnel, students from the College of William and Mary, and archival data compiled by the project historian.

A succinct, descriptive narrative was prepared that documents developmental events that may have left an imprint upon the archaeological record. Five appendices were compiled for the convenience of city planners:

- Historic resources omitted by cartographers.

- Williamsburg's colonial roads.

- Plats and surveys on file at the Williamsburg-James City County Courthouse that show cultural features and/or subdivisions.

- Plats and surveys on file at the York County Courthouse that show cultural features and/or subdivisions.

- Historic maps used by the project's historian and draftsperson in creating a series of electronic maps.

Cultural Resource Sensitivity Mapping

Upon completion of the research process, the draftsperson began creating a multi-layered electronic base map of the City of Williamsburg. Four layers were produced, one per century of historic occupation. Each layer is a composite based upon data extracted from a substantial number of individual maps and plats.

2Every map provided to the draftsperson by the historian was digitized and saved as a separate drawing. These drawings then were inserted into a base map and scaled in relation to one another. All overlapping and repetitious information was eliminated. The end result was a layer showing the City of Williamsburg's cartographically identifiable cultural resources within a specific century. These layers can be superimposed upon one another as a means of identifying areas that have been in almost continuous use throughout historic occupation. Approximately 70 maps and plats from nine repositories were digitized.

An electronic base map was produced upon which were identified areas deemed most likely to contain prehistoric resources. Prehistoric sensitivity mapping data and a written synthesis were provided by Dennis Blanton of the College of William and Mary. The locations of known archaeological sites were entered into an electronic base map. All computer work was accomplished using AutoDesk's AutoCAD® Release 12.

Data Limitations

The identification of seventeenth century cultural resources within Middle Plantation (later, Williamsburg) is hindered by a dearth of topographically sensitive maps for that period. However, three seventeenth century plats and certain land patents were found to be particularly useful in defining culturally sensitive areas. During the eighteenth century Williamsburg was mapped by highly skilled topographic engineers, whose detailed renderings are of inestimable value in the projection of historic site locations. Nineteenth-century data are sparse and coverage of the Williamsburg area is uneven. Union Army cartographers made note of military features they deemed strategically important but largely ignored other types of cultural resources. Confederate cartographers provided relatively detailed coverage of the northwestern outskirts of the city.

Sketches made by the agents of the Mutual Assurance Society were found to provide useful information about the number of buildings associated specific properties. However, almost all of the Society's drawings are schematic representations that shed relatively little light upon the placement of individual structures. The Sanborn Insurance Company's maps of Williamsburg contain much useful information, for they were drawn to scale, often with structural detail.

Only one volume of Williamsburg's antebellum court records escaped destruction in 1865 when Richmond was put to the torch.1 However, York County's records essentially are intact. The clerk's office of the Williamsburg-James City County circuit court has an abundance of nineteenth and early-to-mid twentieth century plats and surveys that show cultural features. This contrasts sharply with York County, which has relatively few. The discrepancy probably is attributable to the procedural policies of the two jurisdictions' clerks of court. City surveyors' maps, on file in both courthouses, were helpful in understanding Williamsburg's growth and development.

Prehistoric Site Potential

A map has been prepared showing areas with the highest potential for prehistoric sites. They are defined simply as locations that lie within 500 feet of streams or wetlands (Figure 1). The strength of this pattern is confirmed by the results of archaeological studies across the region. Furthermore, local inventories show that prehistoric sites are at least as common as early historic sites.

There are some qualifiers, however, to the application of such a predictive model:

- Within this zone adjacent to wetlands and streams, locations that are well-drained and minimally sloped will have the highest site potential. Some potential exists, however, for submerged sites within wetlands, especially tidal marshes.

- Areas outside of this wetland margin zone also have potential for prehistoric sites. Sites in these areas tend to occur less frequently (in lower density) and tend to be small, sparse scatters.

Historic Site Potential

Early Settlement in Middle Plantation

In February 1633 the Grand Assembly implemented a proposal to construct a palisade across the James-York peninsula between the heads of Queens and Archer's Hope (College) Creeks, following an intervening ridge-back. By that date Dr. John Pott had patented and seated 500 acres in the "Barren Neck" just west of Tuttey's Neck (near what became the Kingspoint subdivision) and Henry Coney, Robert Martin and John Milnehouse had leaseholds in Coney Borough, to the north of Jockey's Neck. The palisade was intended to cordon off the lower end of the James-York peninsula, which was set aside for the colonists' exclusive use. Workers were conscripted and a 50 acre bounty was offered to every free man who voluntarily established a seat in the Middle Plantation before May 1, 1633. Construction of the palisade commenced immediately and shortly thereafter, a small settlement took root. The Middle Plantation palisade may have been rebuilt at least once (Hening 1809-1823:I:208-209; Nugent 1969-1979:I:17-18, 22, 89, 91, 94, 142-143, 160-161). Archaeological features discovered on the Bruton Heights School tract (44WB4) most likely are associated with the Middle Plantation palisade, which formed the northwesterly boundary of John Page's 1683 patent (Nugent 1969-1979:I:261) (Figure 2).

A preliminary study of early patents reveals that between 1635 and 1650 a few individuals came into possession of 1,200 to 1,250 acre tracts near the palisade or the horse path that ran through Middle Plantation. For example, George Menefie (later, Richard Kemp), William Davis (Davies), Charles Leach, and Richard Popeley were in possession of tracts of 1,200 or more acres that abutted the palisade or the horse path that ran through the area. As Middle Plantation became more populous, most of these large patents were subdivided into smaller parcels that were leased to tenants or sold. For example, William Sherwood and John Tulitt of Jamestown purchased part of Richard Popeley's vast patent and during the 1650s erected "three lengths of housing," which

4

Figure 1. Prehistoric sensitivity map.

Figure 1. Prehistoric sensitivity map.

Figure 2. Seventeenth-century layer superimposed on 1906 base map.

5

location is uncertain (Nugent 1969-1979:I:105, 112-113, 160, 204, 225; II:261). Others, such as Nicholas Sebrell, Stephen Hamblyn, Edward Whitakers, John Bates, and John Saines, patented lesser sized tracts, which they enlarged as time went on (Nugent 1969-1979:I:95, 102, 106, 110, 316). All of these people were obliged to use or lose their land.

Figure 2. Seventeenth-century layer superimposed on 1906 base map.

5

location is uncertain (Nugent 1969-1979:I:105, 112-113, 160, 204, 225; II:261). Others, such as Nicholas Sebrell, Stephen Hamblyn, Edward Whitakers, John Bates, and John Saines, patented lesser sized tracts, which they enlarged as time went on (Nugent 1969-1979:I:95, 102, 106, 110, 316). All of these people were obliged to use or lose their land.

Jamestown merchant George Menefie developed a plantation he called Littletown upon the 1,200 acre Rich Neck tract, where he had an orchard and garden that in March 1633 inspired David DeVries' admiration. In February 1638 Menefie sold Rich Neck to Richard Kemp, who repatented it in January 1639. Kemp enhanced Rich Neck's size through the acquisition of 100 acres that lay between the Menefie tract and the palisade and then added another 840 acres. Kemp's 1643 patent notes that seven years later he would become eligible for an additional 2,192 acres. In 1642 when John Senior made a plat of Kemp's land at Middle Plantation, he included 4,332 acres: 1,200 acres bought from Menefie, 100 acres adjacent to the palisade, 840 additional acres, and the 2,192 acres Kemp would become eligible for in 1650. Senior delimited 50 acres abutting the palisade that Kemp was leasing to William Davis and the acreage he was renting to Mr. Thomas Hill. Shown prominently within Kemp's original 1,200 acres was a three-building domestic complex in the immediate vicinity of 44WB52. Also depicted was a solitary dwelling below "the Little Creek" on property preliminary research suggests belonged to John Davis. The Davis house probably was destroyed when the Williamsburg Landing retirement community was constructed (Nugent 1969-1979:I:143; DeVries 1857:34; Senior 1642). 44WB49 and 44WB81, tentatively identified as mid-seventeenth century domestic sites, probably are associated with the leaseholds of William Davis and Mr. Thomas Hill, Richard Kemp's tenants (Senior 1642). 44JC145 also is located upon the Kemp property. Other archaeological features associated with this very early phase of Middle Plantation's development await discovery.

During late July and early August 1676, when the colony was caught up in the popular uprising known as Bacon's Rebellion, rebel leader Nathaniel Bacon Jr. held a conference at the residence of Captain Ortho Thorpe in Middle Plantation, making it his temporary headquarters. By that date Major John Page and several other notables had homes in the community and a magazine for the storage of weapons and ammunition had been built there (Washburn 1957:72, 90, 123). The rebel William Drummond was tried and sentenced to death at Middle Plantation in February 1677 and a group of the king's soldiers was stationed there the following summer. After the rebellion was quelled, Captain Ortho Thorpe, Major John Page, Mr. John Bray and Secretary Thomas Ludwell of Middle Plantation presented claims for personal losses they had suffered in the tumult (Neville 1976:30, 274, 378-380).

In 1678 when Robert Beverley surveyed the northeastern corner of Colonel Philip Ludwell's Rich Neck tract and apportioned it into three parcels, he identified the right-of-way of the "road to New Kent" (now Richmond Road), a bridge that crossed College Creek near what became the Rich Neck Mill, a spring, and "the negros quarter." Thomas Ballard purchased the southerly part of the tract Beverley surveyed. Later, it became the campus of the College of William and Mary (Beverley 1678) (Figure 3).

On May 29, 1679, when several Indian kings and queens joined Virginia officials in signing the landmark document known as the Treaty of Middle Plantation, they convened at the magazine, where a formal ceremony was held (Neville 1976:287). The

6

Figure 3. Richard Kemp 1642 survey with Philip Ludwell's 1678 survey superimposed.

precise location of the Middle Plantation magazine is unknown. Although a substantial domestic complex belonging to the Page family has been identified archaeologically and eleven other seventeenth century sites have been pinpointed within the Historic Area, many other cultural features associated with Middle Plantation await discovery through systematic archaeological survey work and archival research (Brown 1992:2, 8-9) (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Richard Kemp 1642 survey with Philip Ludwell's 1678 survey superimposed.

precise location of the Middle Plantation magazine is unknown. Although a substantial domestic complex belonging to the Page family has been identified archaeologically and eleven other seventeenth century sites have been pinpointed within the Historic Area, many other cultural features associated with Middle Plantation await discovery through systematic archaeological survey work and archival research (Brown 1992:2, 8-9) (Figure 4).

In 1683 John Page, whose 330 acre patent straddled the central portion of the ridge-back that became the Middle Plantation, agreed to donate 2½ acres of land for the construction of a parish church. Bruton Parish, established in 1674, drew communicants from the territory that extended from College Creek to upper York County's Skimino Creek. The remains of the first Bruton Parish Church are located within the graveyard enveloping the present structure. An analysis of Page's patent reveals that its origin lay in the landholdings of Richard Popeley (in York County) and Robert Higginson (in James City County) and that it was fragmented into smaller tracts that Page gradually consolidated (Nugent 1969-1979:I:261; Cocke 1964:170; Brown 1992:5) (Chart 1).

On February 8, 1693, King William and Queen Mary granted a charter to the College of William and Mary. Later in the year 330 acres of James City County land were purchased from Thomas Ballard, the acreage he had bought in 1678. The new college's campus was located west of "the church now standing in Middle Plantation old fields," extended to Archer's Hope Swamp (at the head of College Creek), followed the forerunner of Richmond Road, and straddled the track of Jamestown Road. By 1694 a grammar school had opened "in a little School-House" close to the site where the college's main building was to be erected and in August 1695 the first bricks were laid for what

7

Figure 4. Middle Plantation features shown in relation to CW street plan.

became known as the Wren Building (Hening 1809-1823:III:122; Kornwolf 1989:35-36, 67; Beverley 1947:266; Hartwell et al. 1964:71). The courtyard enveloping the Wren Building, Brafferton and President's House defines that portion of the William and Mary campus which is on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register.

Figure 4. Middle Plantation features shown in relation to CW street plan.

became known as the Wren Building (Hening 1809-1823:III:122; Kornwolf 1989:35-36, 67; Beverley 1947:266; Hartwell et al. 1964:71). The courtyard enveloping the Wren Building, Brafferton and President's House defines that portion of the William and Mary campus which is on the National Register of Historic Places and the Virginia Landmarks Register.

By 1699 a small community, which consisted of a church, an ordinary, several stores, two mills, and a smith's shop, had grown up at Middle Plantation, near the College of William and Mary. Only the sites of the church and college are known with certainty. None of Middle Plantation's commercial facilities have been discovered. Very little is known about the community's layout or its domestic sites, few of which have been identified. On April 27, the colony's assembly convened at the college because the statehouse at Jamestown had been destroyed by fire. Several days later, a group of students urged the burgesses to make Middle Plantation the colony's capital, pointing out that the site was well situated for trade and that the college's presence would attract tradesmen and other skilled workers (Anonymous 1930:322; Reps 1972:141-142).

The Establishment of Williamsburg

The burgesses with little deliberation passed "An Act Directing the Building the Capitoll and the City of Williamsburgh," which was named for King William, the Duke of Gloucester. The 220 acre town site, which was situated at Middle Plantation, straddled the line between James City and York Counties, enveloping a substantial portion of John Page's 330 acre patent. Duke of Gloucester Street, which ran along the ridge-back that separated the drainages of the James and York Rivers, formed the central axis of the

8

Chart 1.

9

town, which was to be laid out regularly into half-acre lots. Provisions were made for Williamsburg to be served by two landings or inland ports: Queen Mary's Port on Queens Creek in York County and Princess Anne's Port on College Creek in James City County (Hening 1809-1823:III:197,419-432). By the 1730s, the tandem ports had become known as the Capitol and College Landings, in accord with their proximity to two well known local landmarks: the capitol building and the College of William and Mary. In 1699 Theodorick Bland was commissioned to lay out Williamsburg and its ports, along with the roadways that linked them, the forerunners of Capitol Landing Road and South Henry Street (Figure 5). To curb the appetite of real estate speculators, the burgesses stipulated that no lots would be sold before October 20, 1700, "to the end that the whole country may have timely notice of this act and equal liberty in the choice of the lots." The new community was destined for success, for the spread of settlement inland was accompanied by steady growth in Virginia's population. In September 1701 the governor's council authorized compensation for those whose land had been taken for the new city. A few months later a Swiss visitor observed that Williamsburg was "staked out to be built." A "church, college and state house, together with the residence of the Bishop [Commissary], some storehouses and houses of gentlemen and also eight ordinaries or inns, together with the magazine" already were in existence (Hinke 1916:26). In May 1704 the assembly resolved that "four old houses and [an] Oven" that stood in the middle of Duke of Gloucester Street were to be razed and their owner, John Page, reimbursed (McIlwaine 1918:309-310, 394-395).

Chart 1.

9

town, which was to be laid out regularly into half-acre lots. Provisions were made for Williamsburg to be served by two landings or inland ports: Queen Mary's Port on Queens Creek in York County and Princess Anne's Port on College Creek in James City County (Hening 1809-1823:III:197,419-432). By the 1730s, the tandem ports had become known as the Capitol and College Landings, in accord with their proximity to two well known local landmarks: the capitol building and the College of William and Mary. In 1699 Theodorick Bland was commissioned to lay out Williamsburg and its ports, along with the roadways that linked them, the forerunners of Capitol Landing Road and South Henry Street (Figure 5). To curb the appetite of real estate speculators, the burgesses stipulated that no lots would be sold before October 20, 1700, "to the end that the whole country may have timely notice of this act and equal liberty in the choice of the lots." The new community was destined for success, for the spread of settlement inland was accompanied by steady growth in Virginia's population. In September 1701 the governor's council authorized compensation for those whose land had been taken for the new city. A few months later a Swiss visitor observed that Williamsburg was "staked out to be built." A "church, college and state house, together with the residence of the Bishop [Commissary], some storehouses and houses of gentlemen and also eight ordinaries or inns, together with the magazine" already were in existence (Hinke 1916:26). In May 1704 the assembly resolved that "four old houses and [an] Oven" that stood in the middle of Duke of Gloucester Street were to be razed and their owner, John Page, reimbursed (McIlwaine 1918:309-310, 394-395).

In October 1705, when the third in a series of town-founding acts was passed by the colony's assembly, the 1699 legislation that had established Williamsburg and its sister ports was reaffirmed. This time, however, provisions were made for implementation. In 1705 the layout and dimensions of Williamsburg and its landings were described precisely as they had been in the text accompanying Theodorick Bland's June 2, 1699 survey. Trustees were appointed and authorized to sell the town's lots, which had to be developed within 24 months of the date of purchase or be forfeited. The size of Williamsburg's lots was proscribed by law and restrictions were placed upon the dimensions, character and placement of the buildings that lot-owners could erect. An exception, however, were four half-acre lots acquired by Benjamin Harrison Jr. when the city was first laid out, for he already had built upon them. Structures erected along Duke of Gloucester Street had to conform with height and set-back rules. The lots in Queen Mary's and Princess Anne's Ports were no more than 60 feet square and "a sufficient quantity of land at each port or landing place" was left as a commons (Hening 1809-1823:III:419-431; Bland 1699). Archaeological tests at both ports, which are registered landmarks, indicate that both College Landing and Capitol Landing were well developed suburbs of Williamsburg. It is likely that both areas contain many undetected sites.

Although Williamsburg's trustees originally had a plat depicting the configuration of its ports' lot lines, that document was lost or destroyed sometime prior to 1774 when Matthew Davenport was hired to resurvey them (Davenport 1774; Figure 6). Merchants, planters, artisans and ordinary-keepers were among those who owned and developed lots in Williamsburg and its sister ports and some people had one or more lots in both places. In 1715 the seat of the James City County court was shifted to Williamsburg and some time before 1721 a county courthouse was erected at the corner of Francis and

10

Figure 5. Tracing of Theodorick Bland's 1699 survey of Williamsburg with Capitol Landing and College Landing.

Figure 5. Tracing of Theodorick Bland's 1699 survey of Williamsburg with Capitol Landing and College Landing.

Figure 6. Matthew Davenport's 1774 survey of Princess Anne Port (College Landing).

11

England Streets on Lot 204. The city and county shared the building for more than 40 years by mutual agreement (Gaines 1969:23, 26-27; Palmer 1968:I:169).

Figure 6. Matthew Davenport's 1774 survey of Princess Anne Port (College Landing).

11

England Streets on Lot 204. The city and county shared the building for more than 40 years by mutual agreement (Gaines 1969:23, 26-27; Palmer 1968:I:169).

In 1717 Williamsburg's inhabitants asked the assembly for a charter of incorporation, which received formal approval on July 22, 1722. Williamsburg's city officers consisted of a mayor, recorder, six alderman and a dozen common councilmen. The first city officials, who were appointed, had the right to choose their successors. All but the councilmen served as justices of a monthly hustings court. Williamsburg could have up to two weekly market days (Wednesdays and Saturdays) and two annual fairs (December 12 and April 23). Taxes on sales that took place during market days went toward the city's operating expenses (Barrow 1967:11-14, 25, 46, 49).

Williamsburg, an Urban Center

In 1722-1724 the Rev. Hugh Jones stated that near Bruton Parish Church was "a large octagon tower, … the magazine or repository of arms and ammunition," which was remote from everything but the courthouse. Although Williamsburg had some brick dwellings, most were frame. He said that a rich array of goods was available in local stores and that numerous artisans had moved to the city. He noted that "the servants here, as in other parts of the country, are English, Scotch, Irish, or Negroes." Edward Kimber, an English tourist, was less favorably impressed, for he described Williamsburg was "a most wretched contriv'd Affair for the Capital of a Country" with "nothing considerable in it, but the College, the Governor's House and one or two more" (Jones 1956:70-71, 74, 77-79; Kimber 1907:23) .

Williamsburg's Hustings Court was authorized to try minor cases of indebtedness from all jurisdictions. Its well-earned reputation for rendering swift justice made it popular with litigants from all over Virginia. In 1745 city officials acquired William Levingston's old playhouse on Palace Green so that they could hold "Common Halls and Courts of Hustings." Two years later the capitol burned, destroying many of the colony's governmental records. Shortly thereafter, a public records office was built (Gaines 1968:23, 26-27; Palmer 1968:I:169; Barrow 1967:61-62).

As the city grew, land adjacent to its original boundaries was surveyed and parceled into lots. In 1749 William Waller laid out a series of lots abutting what became known as Waller Street and Capitol Landing Road. In 1752 Benjamin Waller sold part of the new subdivision to Christopher Ford. In 1759 when Williamsburg's corporate limits were expanded, the Waller subdivision and lots along Page and York Streets were included. In 1762 Mathew Moody sold 6 1/3 acres to John Greenhow and made provisions for streets to be laid out. The plats for these subdivided properties are shown on a map composite that includes some contiguous parcels (York County Deed Book 1741-1754:216, 219, 222-223, 344, 473; 1755-1763:396-400; Hening 1809-1823:VII:316; Reps 1972:183) (Figures 7 and 8).

In November 1769 the House of Burgesses authorized the court justices of Williamsburg and James City County to build a new brick courthouse for both to use. Because the preferred site was on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street in York County, a small plot of ground between Nicholson Street and "the line of Hugh Walker's lot on the west and the pailing where H. Dixon's store is on the east" was annexed to James City County. James City's justices sold the old courthouse lot at a public auction,

12

Figure 7. William Waller's subdivision, 1749.

Figure 7. William Waller's subdivision, 1749.

Figure 8. 18th-century plats of Williamsburg.

13

at which time it was purchased by Robert Carter Nicholas. The 1770 courthouse, which was completed by 1772, was shared by the city and county until 1930, when the site upon which it stood was purchased by the Rockefellers. A brick clerk's office near the powder magazine reportedly was pulled down by Union soldiers during the 1860s (Hening 1809-1823:VIII:405, 419; McIlwaine 1918:1404, 1420; Tyler 1928).

Figure 8. 18th-century plats of Williamsburg.

13

at which time it was purchased by Robert Carter Nicholas. The 1770 courthouse, which was completed by 1772, was shared by the city and county until 1930, when the site upon which it stood was purchased by the Rockefellers. A brick clerk's office near the powder magazine reportedly was pulled down by Union soldiers during the 1860s (Hening 1809-1823:VIII:405, 419; McIlwaine 1918:1404, 1420; Tyler 1928).

During the third quarter of the eighteenth century Williamsburg was authorized to hold an unlimited number of market days and to build a market house, a structure that one Revolutionary War cartographer indicated lay on the south side of Duke of Gloucester Street, east of the courthouse and adjoining Market Square. It may have been the large rectangular building that an anonymous French cartographer (1782) indicated stood midway between the Powder Magazine and Lot 13 (Dewitt 1781). During a 1768 smallpox epidemic, a house was rented so that the sick could be sequestered to prevent the spread of contagious disease (Barrow 1967:46, 49).

On February 21, 1774, the residents of Williamsburg were jostled by an earthquake and a strong after-shock that occurred two days later. Although the effects of the quake are uncertain, in nearby Charles City County some buildings reportedly were jarred from their foundations. Ebenezer Hazard, who arrived in the city in May 1777, complained about the quality of its water, which he termed "vile" (Pennsylvania Gazette, February 24, 1774; Shelly 1954:410-411).

The Revolutionary War and Relocation of the Capital

In May 1776, when British General Henry Clinton invaded North Carolina and Virginia troops went to oppose him, state officials feared that Williamsburg might come under attack. On June 12, 1779, a decision was made to relocate the seat of Virginia's government to Richmond, a site deemed less vulnerable. On April 7, 1780, the state's executive department ceased transacting business in Williamsburg and on April 24th it resumed its duties in Richmond. The following week, the General Assembly held its first session in the new capital city (Manerin 1984:139-140; Reps 1972:189).

Relocating the capital had a profound effect upon Williamsburg, which no longer was at the hub of Virginia's social and political life. After the war ended, the Tidewater region's population dwindled and the city's vitality continued to wane. In 1783 one visitor described Williamsburg as "a poor place compared with its former splendor" and noted that as soon as the capital moved to Richmond, "merchants, advocates, and other considerable residents took their departure as well" (Reps 1972:189) . The veracity of that statement is open to scholarly debate.

French cartographers mapping Williamsburg at the close of the Revolutionary War recorded numerous features that are critically important in understanding the city's built environment. They identified public buildings, such as Bruton Parish Church, the capital, Governor's Palace, the Public Hospital, but one also showed a windmill that stood near the northeast corner of the intersection formed by South Henry Street and Newport Avenue. Some of these map-makers labeled troop encampments, domestic complexes, and features on the outskirts of Williamsburg. Many of these peripheral sites, which lie within today's city limits, have not been investigated by archaeologists or historians. They have been synthesized and shown on a map composite, the eighteenth-century layer (Desandrouin 1781; Berthier 1781; Anonymous 1781, 1782) (Figures 9-12).

14 Figure 9. Alexander Berthier, Camp a Williamsburg, le 26th Septembre 1781.

Figure 9. Alexander Berthier, Camp a Williamsburg, le 26th Septembre 1781.

Figure 10. The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg,1782.

Figure 10. The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg,1782.

Figure 11. Nicholas Desandrouins, Carte des Environs de Williamsburg, 1781.

Figure 11. Nicholas Desandrouins, Carte des Environs de Williamsburg, 1781.

The Early National Period

Despite the relocation of Virginia's capital, Williamsburg remained the seat of city and county government. During the first half of the nineteenth century, when court was in session, people flocked into town, often with their families in tow. In 1818 the construction of a canal from College Creek to Williamsburg was proposed. Although the waterway never was built, its right-of-way was mapped out (Ladd 1818). A visitor in 1835 wrote that the city had an asylum; a college; a courthouse and jail; Episcopal, Methodist, and Baptist churches; 16 stores; three tanyards; a saddler's shop and four nearby merchant mills. The city's older public buildings evinced "the appearance of decaying grandeur." A black woman born in Williamsburg in 1845 recalled that there was a whipping post in the ravine near the corner of Francis and South England Streets and that slave auctions were held on the courthouse green where blacks were hawked to the highest bidder (Carson 1961:99; Baker 1933:3, 5). Many of these early-to-mid nineteenth century sites have not been identified archaeologically. Since detailed cartographic works are not available, they must be sought through systematic survey work.

The Civil War

Shortly after war broke out between North and South and Richmond became capital of the Confederacy, it became apparent that the Union military presence at Fort Monroe posed a serious threat. In 1861, when Richmond was inadequately defended against a Union Army advance, Confederate military leaders decided to fortify the lower peninsula so that their adversary's progress would be slowed. Colonel John B. Magruder fixed upon the plan of building three parallel lines of earthworks across the peninsula, making maximum use of the region's steep ravines and water courses. Magruder's westernmost band of earthworks, which became known as the Williamsburg Line, extended from Tuttey's Neck at the head of College Creek to Cub Run, a tributary of Queens Creek. Fort Magruder, a strong and complex earthen feature that was situated above the junction of two public roads, formed the centerpiece of the Williamsburg Line (Webb 1881:37-43). Colonel Benjamin S. Ewell, a West Point graduate and President of the College of William and Mary, was the architect of the Williamsburg Line. Slaves and free blacks were conscripted to help Ewell and his men build the redoubts located within the city limits, near Tuttey's Pond and the trailer park on Quarterpath Road. The archaeological remains of these features have been identified and designated 44JC56, 44JC57, and 44JC58. It is likely that other Civil War sites are yet to be discovered within the city limits (McAlester 1862; Hope 1862) (Figures 13 and 14). According to an account by Colonel Ewell, the Williamsburg Junior Guard had a training field on Capitol Landing Road that they called Camp Page. Land ownership patterns suggest that it was located on the west side of Capitol Landing Road on property that in 1871 belonged to Dr. R. M. Garrett (Chapman 1984:125, 127-132; Anonymous 1871) (Figure 15).

In early May 1862 the Union Army, under the overall command of General George B. McClellan, swept up the peninsula and seized control of Williamsburg. Although its drive toward Richmond proved unsuccessful, the city was in Union hands for the duration of the war. Williamsburg, which was the westernmost Union-held community on

17

Figure 13. Sketch of Battlefield and Confederate Works in Front of Williamsburg, VA, May 8th, 1862, by Lieut. McAlester.

the peninsula, provided the opposing sides with an opportunity to spy upon one another. Local residents' accounts reveal that when the city first was occupied, several of its churches were converted into military hospitals and the Wren Building became a supply depot and headquarters of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry. A stately brick dwelling near the site of the colonial capitol (the Vest or Palmer house) was occupied by the Union Army provost who had command of Williamsburg. The men of the 5th Pennsylvania seized the Virginia Gazette's printing presses and began publishing a military newspaper they called The Cavalier, which intermingled war news and propaganda with poetry, literature and public announcements. Later, when Yorktown was made the army's headquarters, Williamsburg was classified as an outpost (The Cavalier, June 25, 1862).

Figure 13. Sketch of Battlefield and Confederate Works in Front of Williamsburg, VA, May 8th, 1862, by Lieut. McAlester.

the peninsula, provided the opposing sides with an opportunity to spy upon one another. Local residents' accounts reveal that when the city first was occupied, several of its churches were converted into military hospitals and the Wren Building became a supply depot and headquarters of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry. A stately brick dwelling near the site of the colonial capitol (the Vest or Palmer house) was occupied by the Union Army provost who had command of Williamsburg. The men of the 5th Pennsylvania seized the Virginia Gazette's printing presses and began publishing a military newspaper they called The Cavalier, which intermingled war news and propaganda with poetry, literature and public announcements. Later, when Yorktown was made the army's headquarters, Williamsburg was classified as an outpost (The Cavalier, June 25, 1862).

Figure 14. Map showing the position of Williamsburg, by Capt. John Hope,1862.

Figure 14. Map showing the position of Williamsburg, by Capt. John Hope,1862.

Figure 15. Vicinity of Williamsburg and Yorktown, Anonymous 1871.

Figure 15. Vicinity of Williamsburg and Yorktown, Anonymous 1871.

During the three years Williamsburg was in the hands of the Union Army, Fort Magruder was manned, and checkpoints were maintained at two entrances to town. One was located on Richmond Road near Casey's Corner (close to the intersection of Ironbound and Richmond Roads) and the other was on Jamestown Road, just west of Ludwell's Mill (Lake Matoaka). At both of these sites market or "line" days were held 19 when Williamsburg's townspeople could barter with their rural neighbors for fresh produce. A band of Confederate guerillas roved the countryside to the west and south of Williamsburg, occasionally ambushing the Union cavalry or slipping into town. On September 9, 1862, the men of Confederate General Henry A. Wise's legion galloped into Williamsburg, dashed down Duke of Gloucester Street and abducted the Union Army provost from his headquarters. Later, a group of outraged and drunken Union cavalrymen put the Wren Building to the torch. Afterward, the windows and doors of the college's buildings were bricked-up and ditches with strong lines, which consisted of palisades defended by chevaux de fris and a trip-wire, were constructed across Richmond and Jamestown Roads at the edge of the campus. Behind the college was an abatis of oak and beech trees, entangled with wire (Charles 1928:2; Cronin 1862-1865:8).

After three years of occupation, Williamsburg, which Union General Philip Kearney called a "lovely sweet College town of charming villas & old mansions" was scarred and dilapidated. William and Mary's main building and the Brafferton, which had been gutted, were hollow shells, grim reminders of the war. A map synthesizing the buildings, encampments and fortifications that existed during the 1860s, though providing uneven coverage of the study area, shows sites that warrant archaeological testing. Superimposed is an 1866 plat of the Bassett Hall property, which identifies Tazewell's mill dam and some buildings near Francis Street (Figure 16).

Reconstruction and Growth (1865-1917)

After the war, Williamsburg, like many other towns in Virginia, began to slowly recover from the war. But the economic problems facing Virginians were staggering. An estimated 20,000 to 30,000 men lost their lives and many thousands of others were permanently maimed as a result of war wounds and disease. The old social order was in disarray, as blacks and whites struggled to redefine their roles in society, and the state's economic system was destroyed. Confederate money and bonds were worthless, inflation was at an all time high, and legal tender was almost nonexistent. Many local families succumbed to bankruptcy.

Despite the pain of Reconstruction, immense progress characterized the 1880s and 90s. Northern capital flowed into the region, creating new business opportunities. In 1881 the Chesapeake and Ohio built a rail line connecting Richmond with Newport News. This provided local agriculturalists with access to urban markets and stimulated commercial development. Real estate speculators placed ads in Northern newspapers promoting the economic opportunities to be found in the Williamsburg area. The Peninsula Bank and Trust Company opened its doors and in 1898-99 an ice plant and a steam laundry became operational. A year later the Williamsburg Knitting Mill commenced its manufacturing operations. These sites are shown upon plats on file in the local courthouse. Around 1890 the first telephone was installed in Williamsburg residence, at a time when the city's population numbered 1,831 (Virginia Gazette, May 12, 1894; March 3, 1950).

Modern improvements, such as sewer and water lines, were installed just before World War I, at which time the old community well by the 1770 courthouse was back-filled. One Williamsburg native, who recalled the city's appearance during the early twentieth century, said that the old knitting mill near the train depot had been converted

20

Figure 16. 19th-century layer.

into a smoke-belching power plant. Duke of Gloucester Street, which lacked pavement and gutters, reportedly was "a mile long, a hundred feet wide and two feet deep," and lined with buildings in varying stages of dilapidation. Private residences were intermingled with businesses. Across from the city-county courthouse were structures that accommodated the post office, the bank and several law offices. Near the colonial powder magazine (then known as the Powder Horn) were unpainted shanties occupied by blacks. At the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street was a plaque that marked the foundations of the old colonial capitol. There, Duke of Gloucester Street flared into a V with side streets that led to Francis Street and Capitol Landing Road. Williamsburg's economy, other than serving as the seat of the city-county and district courts, revolved around the College of William and Mary and the state-run asylum, which in 1894 became known as Eastern State Hospital (Belvin et al. 1982; Larson 1984). In late 1898 or early 1899 the Virginia Gazette published a city directory intended to promote Williamsburg's development. In 1912 a large tract on the north side of Ironbound Road was laid out into streets and platted into the lots of the Roper-Tilledge Subdivision. Development failed to occur, however, and the project eventually was scrapped (James City County Plat Book 2:22).

Figure 16. 19th-century layer.

into a smoke-belching power plant. Duke of Gloucester Street, which lacked pavement and gutters, reportedly was "a mile long, a hundred feet wide and two feet deep," and lined with buildings in varying stages of dilapidation. Private residences were intermingled with businesses. Across from the city-county courthouse were structures that accommodated the post office, the bank and several law offices. Near the colonial powder magazine (then known as the Powder Horn) were unpainted shanties occupied by blacks. At the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street was a plaque that marked the foundations of the old colonial capitol. There, Duke of Gloucester Street flared into a V with side streets that led to Francis Street and Capitol Landing Road. Williamsburg's economy, other than serving as the seat of the city-county and district courts, revolved around the College of William and Mary and the state-run asylum, which in 1894 became known as Eastern State Hospital (Belvin et al. 1982; Larson 1984). In late 1898 or early 1899 the Virginia Gazette published a city directory intended to promote Williamsburg's development. In 1912 a large tract on the north side of Ironbound Road was laid out into streets and platted into the lots of the Roper-Tilledge Subdivision. Development failed to occur, however, and the project eventually was scrapped (James City County Plat Book 2:22).

In November 1901 a fireproof office was built for the clerk of the city-county court, a detached structure that stood upon the green, to the west of the courthouse. It spared the localities' records from destruction in an 1911 fire that gutted the courthouse. 21 Afterward, local officials opted to renovate the old building rather than construct a new one (Gaines 1969:30). It was during the early twentieth century that the Sanborn Insurance Company began producing detailed maps of Williamsburg. The Sanborn maps reveal much about how the city grew and developed between 1904 (when the city first was mapped) and 1930 (when local mapping ceased) (Figures 17-21).

The Modern Era

In 1917, when the United States entered World War I, an influx of workers, employed in nearby government munitions facilities, sought accommodations in Williamsburg. Providing for these newcomers brought unexpected prosperity to the city. Land prices soared and business boomed. Real estate speculators purchased large tracts, which they carved into lots and marketed as developments such as Lakeside Park, Highland Park, East Williamsburg, Bruton Heights, the Lane and Linekin Subdivisions, the Williamsburg Business Annex, Kenton Park, Capitol Heights, and Powhatan Park. Some of these properties, which then were in James City and York Counties, became part of Williamsburg when the city annexed more territory (Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 2:31,33,35,38-39,45-46; York County Plat Book 2:45,69,79,81). At the end of World War I, some Williamsburg residents found it difficult to adjust to the peacetime economy, for local businesses that had boomed during the war afterward languished for lack of support.

During this period Williamsburg held an annual community fair at the Williamsburg Hotel or the college. During the summer months, tent shows called Chautauquas were staged on the courthouse green. Traveling carnivals also pitched their tents there or in fields at the edge of town. Fairs and harness-races occasionally were held in a field off Capitol Landing Road (Belvin et al. 1982).

In 1923 Dr. William A. R. Goodwin, an ardent antiquarian and the former rector of Bruton Parish Church, returned to Williamsburg. He observed that a hodge-podge of modern structures was beginning to obscure what was left of the city's older buildings. Down the center of Duke of Gloucester Street, which had been paved during World War I to accommodate the army convoys passing through town, was an erratic line of telephone poles festooned with wires. Restaurants, laundries, pool rooms, movie theaters and filing stations were intermingled with aging, sagging eighteenth- and nineteenth-century structures. In 1926 Goodwin succeeded in interesting wealthy philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. in restoring Williamsburg to its colonial appearance. To some local people, the infusion of funds was a dream-come-true. Others genuinely resented the disruption of what was a cherished way of life. In time, a corporation was formed to handle the restoration of Williamsburg and teams of specialists began gathering information about colonial life. Williamsburg's streets were paved and shops catering to visitors were built in what became Merchants Square. In October 1934 the restored colonial city officially opened to tourists, at which time, the Raleigh Tavern, the capitol, the palace and a few other buildings on Duke of Gloucester Street were the main attractions (Belvin et al. 1982).

One of the structures acquired by Rockefeller's agents when Williamsburg's restoration first got underway was the old city-county courthouse, built in 1770-1772. By Fall 1932 its exterior had been given a colonial appearance and its interior had been

22

Figure 17. Sanborn insurance map, 1904.

Figure 17. Sanborn insurance map, 1904.

Figure 18. Sanborn insurance map, 1910.

remodeled into a museum for the display of relics. But restoration of the 1770 courthouse necessitated the construction of a replacement. It stood at the intersection of Francis and England Streets, near to the site once occupied by the 1715 courthouse. By December 1932 the new building was ready for use (Belvin et al. 1982; Gaines 1969:30).

Figure 18. Sanborn insurance map, 1910.

remodeled into a museum for the display of relics. But restoration of the 1770 courthouse necessitated the construction of a replacement. It stood at the intersection of Francis and England Streets, near to the site once occupied by the 1715 courthouse. By December 1932 the new building was ready for use (Belvin et al. 1982; Gaines 1969:30).

In January 1930 Congressman Louis C. Crampton introduced a bill into the House of Representatives that gave the Secretary of the Interior the authority to designate historic sites in Jamestown, Yorktown and Williamsburg as part of the Colonial National Monument. All three areas were to be linked by a scenic boulevard. The Crampton Bill was debated hotly by local citizens, many of whom viewed it as a major intrusion of "big government."

In 1932 an Act of Congress and a Presidential Proclamation heralded creation of the Colonial National Monument and the acquisition of all of Jamestown Island except

23

Figure 19. Sanborn insurance map, 1921.

Figure 19. Sanborn insurance map, 1921.

Figure 20. Sanborn insurance map, 1933.

24

Figure 20. Sanborn insurance map, 1933.

24

Figure 21. Sanborn insurance map, 1939.

that portion owned by the the A.P.V.A. Surveyors laid out a boulevard that linked Yorktown and Jamestown and passed through Williamsburg. Ironbound Road was paved to provide additional access to Jamestown. Six years later the City Council tried to preserve restored Williamsburg's ambience by passing ordinances that prohibited certain types of businesses, such as junk yards, from locating within the city limits (Virginia Gazette, January 17, February 14, June 6, 1930).

Figure 21. Sanborn insurance map, 1939.

that portion owned by the the A.P.V.A. Surveyors laid out a boulevard that linked Yorktown and Jamestown and passed through Williamsburg. Ironbound Road was paved to provide additional access to Jamestown. Six years later the City Council tried to preserve restored Williamsburg's ambience by passing ordinances that prohibited certain types of businesses, such as junk yards, from locating within the city limits (Virginia Gazette, January 17, February 14, June 6, 1930).

During the years colonial Williamsburg was being restored, the United States slipped into the economic crisis known as the Great Depression. One of the Roosevelt administration's solutions to the unemployment problem was the Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.), which undertook public works projects. In July 1933 William and Mary administrators asked for C.C.C. workers to develop part of the college's woods into what became known as Lake Matoaka State Park. By early fall the men of the C.C.C. had pitched their tents upon the campus. Later, they erected frame buildings that served as barracks, a mess hall, a recreation building-library, a latrine and wash house, an infirmary and several administrative buildings. C.C.C. projects in the Williamsburg area, which were part of the Emergency Conservation Work (E.C.W.) program, included repairing some of the damage done by the 1932 hurricane. Besides constructing roads, trails and picnic areas in the college woods, C.C.C. workers built a large outdoor amphitheater known as Players Dell in an area adjacent to Lake Matoaka. In 1937 when heavy rains caused Lake Matoaka's spillway to collapse, the men of the C.C.C. repaired the damage. During 1940 and 1941 the C.C.C. planted trees and grass along the Colonial Parkway from Yorktown to Williamsburg and placed fill dirt over a newly completed 25 tunnel beneath under the Historic Area. On April 15, 1942, Williamsburg's C.C.C. camp was closed and its workers were sent elsewhere (Hunter 1990).

During the 1920s and 30s new subdivisions were created as the city's population grew. It was then that Braxton Court and College Terrace were laid out into lots and the Ironbound Farms subdivision was created on the west side of town. The 1930s brought the development of Pollard Park, Capitol Heights and Matoaka Court. Almost all of these subdivisions were developed, at least in part (Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 4:19-20,50; 5:20,29,33; 6:34). Pollard Park and Chandler Court have been added to the Virginia Landmarks Register and are deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places.

When World War II broke out, workers from military bases in nearby York and Warwick Counties and on the lower peninsula stimulated Williamsburg's economy and members of the armed services flocked to town in search of rental housing. Many local people sought employment at Penniman (renamed Cheatham Annex), at the Naval Mine Depot, Fort Eustis, and Camp Peary, and spent their earnings in Williamsburg. It was during this period that Rochambeau Heights, Highland Park, Palace Heights, Pine Crest, Burns Lane, Indian Springs, Bozarth Court Extended, and Ludwell Place were laid out. After the war, Capitol Court was established (York County Plat Book 1 Part 2:523,622; 3:62; Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 7:46; 8:2,13; 9:18; 10:20,36; 12:14).

During the latter part of World War II, the Colonial Parkway tunnel was designated an air raid shelter for Williamsburg. After the war the tunnel was equipped with paving, lights and ventilation. It opened to traffic in 1949. Although it connected Williamsburg with the Yorktown segment of the Colonial Parkway (completed in 1938), it was not until 1957 that the Jamestown segment was finished, linking all three historical attractions. In 1947 the Jamestown Corporation, a non-profit educational group, built an amphitheater at Lake Matoaka and began staging nightly theatrical productions during the summer months. Attendance declined during the 1960s and in 1976 production ceased.

Annexation and Growth

During the early 1920s the city of Williamsburg succeeded in annexing portions of neighboring James City and York Counties. On July 2, 1938, the Virginia Gazette's editor noted that as a result of the city's 1924 annexation suit, Williamsburg had nearly doubled in size. The boundaries of the enlarged city, projected in September 1923, were depicted on a map prepared in 1931 by surveyor Vincent D. McManus (Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 5:21) (Figure 22). In 1941 the city initiated an annexation suit in which it tried to acquire approximately 874 acres of James City County land and a somewhat lesser amount of York County acreage. The proposed annexation would have nearly trebled Williamsburg's size.

During the summer of 1941, when the suit was settled, the city was allowed less land than it sought. Even so, its territory was doubled. Under the terms of the 1941 court agreement, James City and York Counties were compensated for the land they lost (Virginia Gazette July 2, 1938; March 14 and 21, April 18, July 10, September 12, 1941; March 19, 1954). Williamsburg's new boundaries were depicted on Vincent D. McManus's September 8, 1941, corporate line survey of the city. Shown upon a composite in which McManus's survey is used as a base map are several nearby subdivisions

26

Figure 22. Williamsburg map, 1931.

(Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 9:8) (Figure 23). The issue of annexation lay dormant until 1954, when the city tried to acquire the rest of the acreage it had sought in 1941.

Figure 22. Williamsburg map, 1931.

(Williamsburg-James City County Plat Book 9:8) (Figure 23). The issue of annexation lay dormant until 1954, when the city tried to acquire the rest of the acreage it had sought in 1941.

As the 1950s opened, the nation's economy was still riding upon the post-war boom. During this period the number of people living in Virginia grew. By 1960 America's population had increased by almost 40 million, thanks to the "baby boom" that occurred right after World War II. This population explosion created an unprecedented demand for family housing and spurred the proliferation of suburbs throughout the country. Residential development produced an increased need for the public services, fueled business and commercial interests, and both enhanced and drained tax revenues. By the early 1960s 20 percent of Americans were living between Boston, Massachusetts, and Norfolk, Virginia, in an expansive land corridor that enveloped Williamsburg. This demographic shift was a powerful catalyst for change.

By 1960 the population of Williamsburg nearly had doubled. The city attempted to annex nearly three square miles of James City County land and acreage in York County. As a result of the 1962 annexation court decision, Williamsburg's limits were expanded to include a strip of land along Route 60 west to Skipwith Farms; acreage between Lake Matoaka and Route 5; and territory between York and Second Streets. It was then that Highland Park was taken from York County and given to Williamsburg as a means of maintaining an equitable ethnic balance (Virginia Gazette, July 22, 1960). A composite map upon which the city's streets and roads are depicted, along with subdivisions that were laid out during the early-to-mid twentieth century demonstrates the manner in

27

Figure 23. Williamsburg map, 1941.

which Williamsburg has expanded outward from its colonial core. Some of the developments to which wartime housing shortages gave rise failed to thrive. This is especially true of subdivisions that lay somewhat distant from the heart of town (Figure 24).

Figure 23. Williamsburg map, 1941.

which Williamsburg has expanded outward from its colonial core. Some of the developments to which wartime housing shortages gave rise failed to thrive. This is especially true of subdivisions that lay somewhat distant from the heart of town (Figure 24).

A map depicting the distribution of archaeological sites within Williamsburg's city limits suggests strongly that relatively few cultural features have been identified within the western and northwestern portions of the city (Figure 25). Cartographic evidence indicates that this is attributable to a lack of survey work rather than an absence of cultural features. Likewise, there is a critical need for substantive archival research on outlying properties now encompassed by the City of Williamsburg.

28 Figure 24. 20th-century layer.

Figure 24. 20th-century layer.

Figure 25. Known archaeological sites superimposed on 20th-century base map.

Figure 25. Known archaeological sites superimposed on 20th-century base map.

References Cited

- 1781

- Carte des Environs de Williamsburg en Virginie les Armees Francoise et Americaine ont Campes en Septembre 1781. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 1782

- Plan de la Ville et environs de Williamsburg en Virginie. Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1866-1885

- Plan of Bassett Hall. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1871

- Vicinity of Yorktown and Williamsburg. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1930

- Speeches of Students of the College of William and Mary Delivered May 1, 1699. William and Mary Quarterly 10 (2nd Ser.):323-337.

- 1933

- Memoirs of Williamsburg, Virginia. Typescript, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg.

- 1960

- Williamsburg and Norfolk: Municipal Government and Justice in Colonial Virginia. Master's thesis, History Department, College of William and Mary.

- 1982

- Williamsburg Reunion, 1942 and Before. Williamsburg.

- 1781

- Camp a Williamsburg le 26 Septembre, 1781. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1781-1782

- [Untitled map of York and Gloucester]. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1678

- A Map of Land surveyed at the Instance of Mr. Sec. Philip Ludwell and Mr. Thomas Ballard, Major John Page… June 16, 1678. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1947

- History of the Present State of Virginia (1705). L. B. Wright, ed. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- 1699

- Draft of the City of Williamsburg and Queen Mary's Port and Princess Anne's Port in Virginia by Theodorick Bland. Reprint from William and Mary Quarterly Vol. 10 (1st Series) 72 insert; Library of Congress, Washington, DC; reprint from L. G. Tyler, Williamsburg: The Old Colonial Capital, Library of Virginia, Richmond. 30

- 1996

- Prehistoric Site Potential in the City of Williamsburg. Memorandum to Martha McCartney, February 8, 1996.

- 1992

- Research Plan for the Study of Middle Plantation, 1992-1995. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Department of Archaeological Research, Williamsburg.

- 1961

- We Were There: Descriptions of Williamsburg, 1699-1859. Typescript, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1862

- The Cavalier (Williamsburg and Yorktown).

- 1984

- Benjamin Stoddert Ewell: A Biography. College of Wlliam and Mary, History Department thesis, Williamsburg.

- 1928

- Recollections. Typescript, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1862

- Map Showing Position of Williamsburg, Virginia, from Surveys Made by Command of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, May 30, 1862. National Archives Cartographic Center, College Park, Maryland.

- 1862

- Sketch of Battlefield and Confederate Works in front of Williamsburg, Virginia, May 5, 1862. National Archives Cartographic Center, College Park, Maryland.

- 1964

- Parish Lines of the Diocese of Southern Virginia. Richmond, Virginia State Library.

- 1986

- Resource Protection Process for James City, York County, Williamsburg and Poquoson, Virginia, Draft Report II. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- [1862-1865]

- The Vest Mansion, Its Historical and Romantic Associations as Confederate and Union Headquarters in the American Civil War. Transcript, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1781

- Carte des environs de Williamsburg en Virginie. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 1782

- Carte des environs de Williamsburg en Virginie. Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

- 1857

- Voyages from Holland to America, Henry C. Murphy, trans. Collections of the New York Historical Society III (2nd Ser.):1-129. 31

- 1781

- From Allens Ordinary Through Williamsburg to York. Colonial Williamsburg.

- 1969

- The Courthouses of James City County. Virginia Cavalcade Vol. 18 No. 4:20-30.

- 1864

- Vicinity of Richmond and Part of the Peninsula. Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

- 1940

- The Present State of Virginia and the College [1697] by Henry Hartwell, James Blair and Edward Chilton. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

- 1809-1823

- The Statutes At Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia. 13 vols. Samuel Pleasants, Richmond.

- 1916

- Report of the Journey of Francis Louis Michel. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 24:1-43,113-141,275-288.

- 1862

- Map showing the Position of Williamsburg. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1990

- Civilian Conservation Corps (C.C.C.) in Williamsburg, 1933-1942. Williamsburg Area Historical Society. Historical Monograph No. 1 (Williamsburg).

- 1956

- The Present State of Virginia. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- 1907

- Observations in Several Voyages and Travels in America, 1736. William and Mary Quarterly 15 (1st Series):143-159;215-252.

- 1989

- So Good A Design, The Colonial Campus of the College of William and Mary: Its History, Background and Legacy. The College of William and Mary, Williamsburg.

- 1818

- A Plan of that part of the Virginia Canal from College Creek to Williamsburg by Thomas M. Ladd. Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia; Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1984

- The Williamsburg 1944 and Before Reunion. Williamsburg.

- 1984

- The History of Henrico County. University Press of Virginia, Charlottesville. 32

- 1862

- Reconnaissance of Part of the Rebel Works in front of Williamsburg, Evacuated May 6, 1862. Library of Virginia, Richmond; printed in Official Records of the Civil War Plate 20 Map 2.

- 1862

- Sketch of the Battlefield and Confederate Works in Front of Williamsburg, Virginia, May 5, 1862. Library of Virginia, Richmond; printed in Official Records of the Civil War Plate 20 Map 3 and 4.

- 1918

- Legislative Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia. 3 vols. Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- 1976

- Bacon's Rebellion: Abstracts of Materials in the Colonial Records Project. The Jamestown Foundation, Richmond.

- 1969-1979

- Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants. 3 vols. Dietz Press, Richmond and Genealogical Publishing Company, Baltimore.

- 1968

- Calendar of Virginia State Papers. 11 vols. Kraus Reprint, New York.

- 1774

- Pennsylvania Gazette. February 24, 1774 edition, Philadelphia.

- 1972

- Tidewater Towns: City Planning in Colonial Virginia and Maryland. University of Virginia Press, Charlottesville.

- 1642

- Survey of Richard Kemp's Land. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Archives, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1954

- The Journal of Ebenezer Hazard in Virginia, 1777. Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 62:400-423.

- 1928

- Williamsburg: The Old Capital. Williamsburg.

- 1894-1960

- Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg.

- 1972

- The Governor and the Rebel: A History of Bacon's Rebellion in Virginia. W. W. Norton, New York.

- 1881

- The Peninsula: McClellan's Campaign of 1862. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York. 33

- 1865-1955

- Plat Books. Williamsburg-James City County Courthouse, Williamsburg.

- 1747-1955

- Deed Books, Plat Books. York County Courthouse, Yorktown.

Appendix 1.

Historic Resources Omitted by Cartographers

References to the following cultural features were encountered during the research process. They are not shown on historical maps.

17th century resources:

- almost all of the homesteads established by those who first seated at Middle Plantation.

- the College Creek line of the Middle Plantation palisade

- much of the Queens Creek line of the Middle Plantation palisade

- the 1676 magazine built at Middle Plantation

- the "three lengths of housing" built by William Sherwood and Thomas Rabley during the mid-17th century

- cultural features associated with the African-American presence

- early commercial, industrial and domestic sites at Middle Plantation, extant in 1699 when Williamsburg was laid out (an ordinary, several stores, two mills and a smith's shop)

- the Middle Plantation homes occupied by John Bray, Ortho Thorpe and others

- features associated with Bacon's Rebellion

18th century resources:

- the courthouse first used by Williamsburg-James City County

- cultural features at College and Capitol Landings: ordinaries, industrial sites, domestic sites, public warehouses, tobacco inspection stations; public wharfs

- industrial sites at the edge of town

19th century resources:

- Tazewell's Mill

- Confederate and Union military encampments and features associated with the Battle of Williamsburg

- industrial, commercial and domestic sites in sectors of the city not mapped by military cartographers

- training field used by the Williamsburg Junior Guard

- sites associated with Union occupation of Williamsburg

- sites used by the Confederate prior to their withdrawal

- the whipping post in the ravine near the 1770 courthouse

Appendix 2.

Williamsburg's Colonial Roads

The following Williamsburg roads are listed in accord with their first appearance upon historical maps or their citation in other documentary sources.

17th century roads:

- the Middle Plantation horse path (Duke of Gloucester Street)

- the road to Jamestown (Jamestown and Mill Neck Roads)

- the road to New Kent (Richmond Road)

- the road to Princess Anne's Port (South Henry Street)

- the road to Queen Mary's Port (Capitol Landing Road)

- the road to York (Penniman Road)

18th century roads:

- streets laid out as part of Williamsburg's original grid plan

- Page Street

- Waller Street

- Ironbound Road

- Longhill Road

- Strawberry Plains Road

- Quarterpath Road

Appendix 3.

City Plats in the Williamsburg-James City County Courthouse

The following plats depict newly created subdivisions and/or cultural features.

- 1939

- Dec. 15, 1939, Pine Crest Subdivision. Plat Book 8:13.

- 1942

- November 23, 1942, Map to be Used in Conjunction with Plan of Williamsburg. Plat Book 10:12.

- 1950

- October 12, 1950, James Terrace. Plat Book 12:16.

- 1928

- Plat A of Block 13-1, Williamsburg Holding Corp. Plat Book 4:15.

- 1928

- March 13, 1938, Plat of Property to be conveyed to Virginia Electric Power Company. Plat Book 4:19.

- 1928

- Plat of Braxton Court. Plat Book 4:19.

- 1930

- May 1930, Plan of Pollard Park. Plat Book 5:20.

- 1912

- December 28, 1912, Map of the Roper-Tilledge Subdivision. Plat Book 2:22.

- [ca. 1916]

- Plat of Capitol Heights, Williamsburg, Virginia. Plat Book 2:31.

- 1916

- March 1916, Fort Magruder Terrace. Plat Book 2:32.

- 1916

- June 1916, Williamsburg Annex, Section A. Plat Book 2:38.

- 1916

- June 12, 1916, Powhatan Park. Plat Book 2:45.

- 1934

- November 2, 1934, Capitol Heights. Plat Book 6:35.

- 1936

- June 25, 1936, Map to Show Agreement with Williamsburg Restoration Inc. Plat Book 7:47.

- 1924

- June 24, 1924, Plat of Cedar Grove Cemetery. Plat Book 3:24.

- 1922

- August 1922, Plat of land of M. L. Norvell and Robt. M. Kent in Williamsburg and Bruton District. Plat Book 3:20.

- 1948

- July 7, 1948, Bassett Hall. Plat Book 11:24. 37

- 1938

- November 1938, Fort Magruder Heights. Plat Book 7:50.

- 1945

- March 21, 1945, Plat of Magruder View owned by John W. Newton in James City County. Plat Book 11:16.

- 1928

- March 1928, Plat of College Terrace. Plat Book 4:20.

- 1903

- November 16, 1903, Plat of 15 acres adjacent William and Mary and the Bright Farm. Plat Book 1:4.

- 1938

- Idlewood, property of Mrs. M. R. Bucktrout, 1938. Plat Book 7:7.

- 1946

- March 1946, subdivision of Burns Lane. Plat Book 10:36.

- 1916

- July 10, 1916, Kenton Park. Plat Book 2:39.

- 1921

- December 10, 1921, Revised Plat of Kenton Park. Plat Book 3:10.

- 1926

- January 4, 1926, Plat of Standard Oil Company Property. Plat Book 3:37.

- 1925

- October 20, 1925, Property Formerly Belonging to Williamsburg Power Company. Plat Book 4:5.

- 1930

- June 24, 1930, Plat of Capitol Heights. Plat Book 4: 50.

- 1916

- March 1916, Williamsburg Business Annex. Plat Book 2:35.

- 1930

- June 10, 1930, Plat of P. O. Peebles Property in Williamsburg and James City County. Plat Book 5:2.

- 1930

- Plat of Page Randall's Estate on York Street. Plat Book 5:22.

- 1930

- March 17, 1930, Plat of Property of George Rollo. Plat Book 6:41.

- 1931

- June 6, 1931, Map of Williamsburg Methodist-Episcopal Church. Plat Book 5:26.

- 1936

- November 14, 1936, Plat for the Texas Company. Plat Book 7:2.

- 1938

- January 1, 1938, Property of Colonial Oil Company. Plat Book 7:17.

- 1939

- May 29, 1939, Indian Springs subdivision. Plat Book 7: 46.

- 1939

- September 8, 1939, Bozarth Court Extended. Plat Book 8:2.

- 1942

- November 1, 1942, Highland Park Development. Plat Book 9:18.

- 1946

- January 22, 1946, Plat of Ludwell Place. Plat Book 10: 20. 38

- 1947

- July 1, 1947, Ludwell Place subdivision. Plat Book 11: 5.

- 1950

- January 31, 1950, Plat of Capitol Court. Plat Book 12:14.

- 1930

- July 11, 1930, Proposed Addition to Cedar Grove Cemetery. Plat Book 5:3.

- 1926

- Aug. 10, 1926, Plat of Property of W. L. Jones. Plat Book 4:2.

- 1935

- April 1935, Plat of Matoaka Court. Plat Book 6:34.

- 1931

- October 7, 1931, Plat showing Norton-Cole house, Peachy house, courthouse green and various streets. Plat Book 5:31.

- 1930

- November 7, 1930, Location Plan of New Courthouse. Plat Book 5:38.

- 1919

- December 10, 1919, Plan of the Coke Place in Williamsburg. Plat Book 2:15.

- 1907

- May 3, 1907, Plat showing lot extending from Henry St. to Boundary St. in Williamsburg. Plat Book 2:6.

- 1912

- August 19, 1912 plat, Map of Part of the O'Keef Property, West End, Williamsburg. Plat Book 2:20.

- 1900

- June 20, 1900, Plat of the Matty School property. Plat Book 1:3.

- 1901

- March 1901 plat of lot enclosed by Prince George, Henry, Boundary and Scotland Streets. Plat Book 1:8.

- 1901

- February 15, 1901, Plat of Greenhow Lot I, formerly Rosetta Tucker. Plat Book 1:8

- 1902

- October 9, 1902, Plat of land on College Creek, part of Delks, adjacent W. L. Jones. Plat Book 1:10.

- 1903

- May 8, 1903, Plat of Land East of College Mill Land. Plat Book 1:13.

- 1905

- November 4 and 5, 1905, Plat of Upper Part of Capt. R. A. Bright's farm. Plat Book 1:14.

- 1928

- May 15, 1928, Survey and plat of small piece of Meadowland owned by Virginia B. Houghwort. Plat Book 5:48.

- 1928

- June 1928, Ironbound Farms. Plat Book 5:29, 33.

- 1924

- December 1924, Plat of Pottstown. Plat Book 3:31. 39

- 1924

- Map of Lake Matoaka and Adjacent Property. Plat Book 3:32.

- 1925

- September 1925, West Williamsburg Heights. Plat Book 3:33.

- 1925

- June 13, 1925, Plat of Property of H. D. Bozarth. Plat Book 3:36.

- 1926

- September 1926, Plat of Property of C. J. Person. Plat Book 4:11.

- 1928

- October 12, 1928, T. H. Geddy's lot on north side of York Street. Plat Book 4:26.

- 1929

- January 18, 1929, Plat of Property of George Rollo. Plat Book 4:29.

- 1939

- March 5, 1939 map of Williamsburg Restoration Survey for Williamsburg Holding Corp. Plat Book 7:37.

- 1929

- May 1, 1929, Plat of Peachy House and Property. Plat Book 4:49.

- 1916

- April 1, 1916, Plat of Highland Park. Plat Book 2:33.

- 1916