A History of Black Education and Bruton Heights School, Williamsburg, Virginia

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0373

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

2000

A HISTORY OF BLACK EDUCATION AND BRUTON HEIGHTS SCHOOL WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0373

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, VA 23187

March 1997

Contents

| Introduction | 1 |

| PART I: Historical Background | |

| From the Colonial Period through the Civil War | 3 |

| Mandated Public Education Includes Black Virginians | 8 |

| Public Education in the South Benefits from Northern Philanthropy | 9 |

| Public Schools come to Williamsburg | 11 |

| African-American Students and Teachers | 12 |

| Black Schools in Williamsburg, 1870-1924 | 14 |

| The Black Community Supports Educational Opportunity | 16 |

| James City County Training School, 1924-1940 | 19 |

| PART II: Bruton Heights School, 1938-1968 | |

| Make Do or Start Over? | 23 |

| Development and Funding of Bruton Heights School | 29 |

| The New School Plant Takes Shape | 34 |

| Bruton Heights School Ready for Occupancy | 36 |

| Faculty and Staff | 37 |

| Curriculum | 39 |

| Bruton Heights School: African-American Community Center | 40 |

| Bruton Heights School During World War II | 45 |

| 1945-1968 | 49 |

Appendices

| Appendix 1: | "Proposed Educational Program for the Occupational and Social Needs of Negroes in the Williamsburg Area." [Report to the General Education Board]. May 12, 1938. |

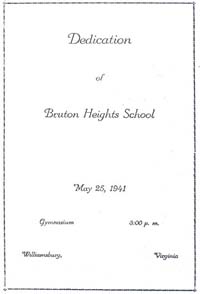

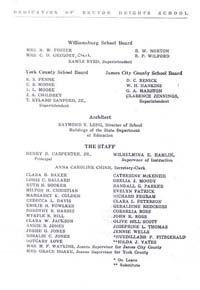

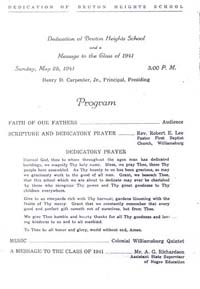

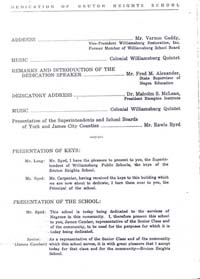

| Appendix 2: | Program for Dedication of Bruton Heights School, May 25, 1941, Williamsburg, Virginia. Printed by the Virginia Gazette Press, Williamsburg, Virginia. |

| Appendix 3: | Actual Needs and Practicable Solutions: Bruton Heights Community School. Charlottesville, Va.: Extension Division Publications, New Dominion Series 41 (November 1, 1943). |

INTRODUCTION

In more than a quarter century as an all-black institution, Bruton Heights School educated a generation of African-American children. Its accomplishments were then and remain today a source of pride in the local African-American community and among its former students, faculty, and staff. Their memories tell of outstanding teachers and supportive parents, who emphasized academic achievement and strong personal values; of enthusiastic students and sports heroes; traditional proms and homecoming parades; and a rich community outreach that included classes for adults, a clinic, a movie theater, and a USO for black soldiers and sailors during World War II. The ever-present backdrop for these stories was the struggle to achieve equal educational opportunity for black children in the Williamsburg area. Poignant recollections also carry a keen sense of loss for the old Bruton Heights School, perhaps best symbolized in the irreverent dispersal of once proudly displayed trophies and awards as officials readied local schools for desegregation in the late 1960s.

Planning and development of Bruton Heights School, and the subsequent history of that institution, are the primary focus of this study. When the city council and school board of the City of Williamsburg made the decision in the late 1930s to build a new public school for local area African-American children, black education for the first time took center stage at the Williamsburg school board. To provide historical context for this significant move forward, the report includes information about public education for both black and white children in Williamsburg beginning with the first meeting of the school board in 1870. A review of the approach to education in Virginia as far back as the eighteenth century broadened that perspective even further.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, African-Americans in Williamsburg knew first hand the bias in favor of white students under the "separate but equal" policy that prevailed in local schools until the late 1960s. As it did elsewhere, the white perspective in Williamsburg on educating blacks at public expense usually took the form of curricula that emphasized vocational training and meager allocations for buildings and supplies.

2To ease inequities, members of the black community around Williamsburg often dug deep in their own pockets to buy educational materials not funded by the school board. In the fullness of time, black citizens became less reluctant to voice their opinions to the board about matters affecting their children's education. When it became clear that Rockefeller investment in Williamsburg's colonial past would breathe new life into the local economy, they made a claim to improved educational opportunity that presaged the development of Bruton Heights School. Ultimately, African-American parents and teachers anticipated with hope and fear, assurance and dread the key to educational parity for children of both races in Williamsburg: desegregation of local public schools, a process not completed until the 1968-69 school year.

Minutes kept by the Williamsburg school board provide a continuous record of public education in Williamsburg from 1870 to the present. School board members discussed African-American students and their schools in Williamsburg right from the start. After an expanded school program for the African-American community came up for discussion in 1938, Bruton Heights School nearly always figured in one or more agenda items at every school board meeting.

Meeting minutes were a mixed blessing. For instance, issues resolved outside official meetings often were not explained fully in the minutes. Likewise, problems introduced at board meetings sometimes appear to have been resolved or dropped without further notation in board records. Some of the blanks could be filled in from Williamsburg City Council minutes, local and regional newspapers (some of them African-American newspapers), the correspondence files at Colonial Williamsburg, and other sources.

What transformed classrooms, blackboards, desks, books, students, and teachers into the vital Bruton Heights School? The Bruton Heights spirit is not to be found in the prosaic record of school board and city council meetings. Not even newspaper articles and correspondence files often captured the real essence of the school. But the written record is not the only source of information about Bruton Heights. Interviews with former faculty, staff, students, and members of the Williamsburg community at large will breathe life into the bare facts assembled here. One of the purposes of this report was to supply accurate background material to be used in taking oral histories.

The report also provided historical information for planners of a permanent exhibition covering the rich and poignant history of Bruton Heights School. The exhibition is located in the lobby of the restored and refurbished school building at the Bruton Heights School Education Center.

This report has two large sections. Part one presents a brief history of education in Virginia and Williamsburg with an emphasis on educational prospects for black people from the colonial period into the post-Civil War era. The history of educational opportunity and development of publicly funded schools for white people is necessarily part of that story. Part two traces the development and funding of Bruton Heights School and focuses on its operations an all-black institution for both elementary and high school students.

PART I

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

From the Colonial Period through the Civil War

Virginia adopted a new constitution in 1869. It included the first outright requirement that the Commonwealth provide free, public education for the youth of the state. The notion of education at public expense mandated by this new constitution was virtually unknown in the South from colonial times through the Civil War. The philosophy of education had been, and remained, that parents provided schooling at a level they could afford and thought appropriate to their children's future prospects. Within this frame of reference, public officials provided very limited educational assistance only to free indigent children.1 Rarely had education for black children been part of the equation.

In eighteenth-century Virginia, education was respected, and literacy a distinct advantage, but the largely oral culture of colonial times encompassed everyone from classically educated gentleman to resourceful slave. Slave children learned from their parents and other adults techniques for survival in a in a society that afforded them little protection. They acquired work skills as they labored alongside adult slaves under the direction of their masters. If this was the experience for most blacks in the colonial period, there is, nevertheless, evidence in Williamsburg and vicinity that a few black children received a "book" education similar to that of some of their white counterparts.

The colonial Virginia legal code did not forbid slaves and free blacks to learn to read and write. Some slave owners even found it expedient to teach a trusted slave to read and do simple arithmetic, but most slave holders balked at the idea of either educating their slaves or introducing them to Christianity. They feared the pride and rebelliousness learning could engender, and literacy often made the difference between a successful or failed escape attempt.2

There is the occasional reference in a will or estate account of resources set aside to pay for the education of an individual slave child. For instance, in October 1754, Elizabeth Wyatt billed William Dawson's estate, 1.6 for schooling his slave Jinny for one year.3 After the Revolution, George Wythe taught Jamie, a young slave boy in 4 his Williamsburg household, to read and write.4 Moreover, among apprentices bound to artisans to learn a trade there were a few slaves and free blacks. Like their white counterparts, by law they would have been eligible to be taught not only the skills of a trade but to read and write as well.5

Religious training brought a measure of education to colonial Virginians including some African-Americans. James Blair, rector of Bruton Parish Church in Williamsburg from 1710 to 1743, advocated Christian education for "Negro & Indian Children." He reported to the Bishop of London in the late 1720s that he encouraged "the baptizing & catechizing of such of them as understand English, and exhort their Masters to bring them to Church and baptize infant slaves."6 Consequently Blair and his successors baptized nearly a thousand slaves between 1739 and the Revolution.7 William LeNeve, minister of nearby James City Parish reported at about the same time that among slaves born in Virginia, he had "examined and improved" several of them. LeNeve used "Directions for the Catechists &c.," printed by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts to "plant that seed among them which will produce a blessed harvest." A few miles from Williamsburg, Francis Fontaine rector of Yorkhampton Parish (covering Yorktown and parts of York County) responded to the bishop that he exhorted masters to send their slaves to him to be instructed and that "in order to their conversion I have set apart every Saturday in the Afternoon and catechize them at my Glebe House." Another minister reported that he baptized slaves in his parish when they could "say the Church Catechism."8

In 1743 Commissary William Dawson wrote to England for a copy of school rules "which, with some little Alteration, will suit a Negro School in our Metropolis, when we 5 shall have the Pleasure of seeing One established."9 Whether Dawson envisioned occasional catechism classes for slaves or more general instruction is unclear, but he later wrote that he visited three of these schools in Bruton Parish.10

More significant for its longevity, continuity, and scope was the school for slave children in Williamsburg funded by the Associates of Dr. Bray, a philanthropic organization allied with the Anglican Church in England. Open from 1760 to 1774, the school ran at capacity (25-30 students at a time) for the whole period. The schoolmistress was Mrs. Anne Wager, formerly tutor to the Burwell children at Carter's Grove and later to a group of white children in Williamsburg. She used the Bible and Anglican religious materials to teach her pupils to spell, read, and speak properly as she communicated Christian doctrine according to Anglican tenets.11 The list of materials sent from England included instructional materials designed for Indians, simple English primers, and catechisms.12

Reports from the eighteenth century tell of slaves imported as adults from Africa understanding too little English to benefit much from religious instruction, but as early as 1724 Hugh Jones noted that "the Native Negroes" were among "the only People that speak true English."13 The large number of native-born slaves in the Williamsburg area were probably no exception.14 Peres, a slave who had lived for many years around Williamsburg, ran away in 1761 after he had become George Washington's property. 6 The newspaper stated that Peres spoke good English, with little evidence of his "Country Dialect."15

At the Bray School, Mrs. Wager undoubtedly amplified the language skills noted earlier by Jones. A broad cross-section of slave owners in Williamsburg and a few free black parents in the vicinity sent their children to the school between 1760 and 1774. While it is likely that Mrs. Wager reinforced her pupils' subservient status with scriptural passages such as "Servants obey your masters," and slave owners all too often found work at home for the children before they could get the intended three years' instruction, the fact remains that Mrs. Wager taught a significant number of black children in Bruton Parish and Williamsburg to "mind their Stops & … to pronounce & read distinctly."16

Advertisements in the Virginia Gazette in the 1760s and '70s give evidence that slaves in some numbers around Williamsburg could read and write, skills still to be found among local slaves early in the next century.17 When a nineteenth-century Baptist historian reported in 1810 that a church book was kept by early members of the black Baptist church founded in Williamsburg in the last quarter of the eighteenth century, it was further confirmation of a subculture of literate slaves in the area.18 What toleration there had been for slave literacy evaporated in the early nineteenth-century, however, as fear of slave rebellion spawned laws against educating slaves.

Education for African-Americans was the exception not the rule from colonial times through the Civil War, but neither was a regularized system of compulsory education the norm for white children. White children in colonial Virginia usually learned the rudiments of reading at home from the Bible or simple primers, often at their mother's (or other female relative's) knee. Continuing the traditional link between education and religion, Anglican ministers in the colony, who wanted to supplement their modest clerical salaries, frequently set up small schools where older children continued their education for a fee.19 Well-to-do plantation owners or town dwellers hired private tutors to prepare their sons for a classical education or sent their boys to 7 the Grammar School at the College of William and Mary. Tutors coached daughters of the gentry in writing and reading for recreational purposes and sometimes taught them simple arithmetic. The College in Virginia or a university abroad awaited sons of the well-to-do.

Less well-off parents arranged apprenticeships for their sons and (less frequently) daughters or paid a teacher to give their children from one to three years' instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic. A few promising young men from families of modest means even received scholarships to attend William and Mary. For white children of destitute parents, the story was much different. The fortunate few attended free schools for a few years, such as the one operated in the middle of the eighteenth century by the Bruton Parish vestry made possible by a bequest in Mary Whaley's will.20 In spite of colonial laws designed to ensure that poor children got basic instruction (including religious), free parents of small means, black and white, often could do no more than pass on practical skills by word of mouth, while their sons and daughters learned by doing.

Between the Revolution and the Civil War the idea of universal public education was slow to take hold. Upper class Virginians looked upon it as intended for paupers, and the poorer classes suffered the stigma associated with accepting aid from the state.21 Conservatives took a dim view of a system for which they would be taxed but had no intention of using themselves. Moreover they were suspicious of the effects of educating the poor claiming it would lead to "disappointed hopes" among the lower classes and thus to unrest and societal instability.22

Having thwarted efforts to create a system of public education in Virginia from Thomas Jefferson's plan in 1779 onwards, the Virginia legislature nevertheless saw fit to establish a Literary Fund in 1810. The act that created the fund ordered that certain small revenues accruing to the state be set aside for the "encouragement of learning." In 1816 the federal government repaid a loan to Virginia (dating from the War of 1812) in the amount of $1,210,550. Virginia legislators added this sum to the accumulating assets in the Literary Fund. Income from the Fund (and poll tax receipts after 1851) was distributed to counties and towns to provide schooling for indigent white children. A board of local officials appointed by the county courts identified appropriate recipients and employed a teacher at the rate of about four cents per pupil for every day they 8 were in actual attendance. In 1829 the General Assembly permitted about 10 percent of the allotments from the Literary Fund to be used to build schoolhouses.23

Mandated Public Education Includes Black Virginians

After peace was declared in 1865, rebuilding the war-ravaged South brought with it the need for better education for southerners of both races. But if the more democratic idea of state aid for education in partnership with localities gained appreciable momentum before the War (expenditures from the Literary Fund increased from $44,000 in 1836 to $214,000 in 1860), the idea still took a back seat after the war to internal improvements such as railroads, turnpikes, and canals. Those were expensive projects, and money was in short supply. To Virginia's public debt, initially acquired in 1838 when Virginia legislators had approved the sale of state bonds to obtain money for internal improvements, had now been added the enormous expense of the war effort itself. In the post-war era, the state's economy and infrastructure were in shambles. Few Virginians were in a strong position economically, and outright poverty was the reality for many whites and most blacks, making for a weak tax base. Such revenues as could be collected were stretched thin. Too thin to support public schools in the opinion of conservative political interests in Virginia. Nor were taxpayers (primarily landowners) prepared to accommodate tax hikes. Conservatives thought limited revenues ought be applied to retiring Virginia's lingering state debt and to attracting new industry. 24 An education mandate that would extend schooling at public expense to white children and children of liberated slaves (former slaves were 30 percent of the total population) was just too costly.

To be sure, many Virginians also dreaded the "leveling" among all ranks in society they thought public education would bring. Moreover, ranking members of Virginia society, suspicious before about the effects of educating poor whites, now viewed educating blacks as having but one purpose forced upon the South by northern interests: to "break down all ranks and put the negro upon a plane of equality with the whites." And the system of doling out money from the Literary Fund had prolonged an 9 unfortunate association in many Virginians' minds between indigence and publicly funded education. 25

In spite of the strength of these opinions, the public school system in Virginia was destined to gain rapid popularity. In 1869 the Virginia constitution makers provided for "a uniform system of public free schools and for its gradual, equal, and full introduction into all the counties of the state by the year 1876." The practical necessity of public education for all Virginians, and for African-Americans in particular, now coupled with an education provision in the new constitution, brought a flurry of activity in the 1869-1871 period supported by the likes of Gov. Gilbert Walker, Gen. Robert E. Lee (then a college president), and others. Drafting school regulations and selecting local school officials fell to the Rev. Dr. William Henry Ruffner, elected state superintendent of schools in 1870.26 In December of that same year, the school board of the City of Williamsburg held its first meeting.

In many localities, including Williamsburg, public education was more enthusiastically embraced in the African-American community than among the white population. Publicly funded schools and a system to run them came at a time in Virginia and the nation when African-Americans actively sought the education that would prepare them to participate successfully as free citizens in the American democracy. Booker T. Washington wrote movingly about that time of the freed peoples' desire for education saying that "it was a whole race trying to go to school. Few were too young, and none too old, to make the attempt to learn." These same sentiments were expressed by a James City County resident in 1871 when he wrote that "great excitement prevails among the colored race. Young and old, little and big, seem eager to obtain knowledge." 27

Public Education in the South Benefits from Northern Philanthropy

Before the end of the Civil War, a number of individuals and religious societies in northern states had responded generously to appeals for aid to escaping slaves and refugee freedmen who sought protection and assistance behind Union lines. Initially, their concern was timely supply of food, clothing, shelter, and medical treatment, but a number of philanthropists and benefit societies turned their attention to matters beyond 10 immediate relief of physical suffering. Among other things, they strongly suggested that schools and churches be organized for these displaced persons.28

A month before the end of the war, Congress created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, commonly called the Freedmen's Bureau. The work of the Bureau was significant for making the care and protection of freed persons part of official structure, but perhaps more significantly, it backed the teachers sent by benevolent societies to establish schools in communities of displaced African-Americans in the South. Wherever these teachers went, they found a strong desire for literacy among recently emancipated African-Americans.29

Among educators who responded to appeals by Union generals was Mrs. Mary Peake, daughter of a slave, who opened the first of these schools at Fortress Monroe in Virginia in 1861. Religious groups and other benefactors in the north, the Freedmen's Bureau, and freed men and women themselves all contributed funds to sustain these schools. Before the educational program under the Freedmen's Bureau reached its five-year mark, benevolent societies aided by the Bureau also had begun to establish a system of colleges and universities for African-Americans. The American Missionary Association established Fisk University, Talladega College, and Atlanta University before turning its attention to the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute of Virginia where Gen. S. C. Armstrong created a program in which "Negro teachers and leaders might be properly trained." In 1868 Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) opened with two teachers and fifteen pupils. The school received a charter from the Virginia legislature two years later. Hampton Institute had the support of the Freedmen's Bureau and northern philanthropists, among them the Rockefeller family.30

The philanthropic impulse benefited public education for both races in the post-war era. A number of foundations made moneys available to southern school systems, not to effect integration, but often for the express purpose of improving educational opportunities for African-Americans. Many southern school boards formed in this period (including Williamsburg's) were chronically short of funds, and black school facilities in Williamsburg and elsewhere usually felt the pinch first. The Slater Fund (founded in 1882 by John Slater, a textile mogul from Norwich, Connecticut), the Anna T. Jeanes Foundation (set up according to the terms of this Philadelphia Quaker's will in 1908), the General Education Board (a Rockefeller foundation incorporated in 1903), 11 and the Rosenwald Fund (organized in 1917 by Julius Rosenwald, a New York industrialist) were among the organizations that eventually had an impact on schools in Williamsburg. These men and women were forward-looking and genuine about their desire to give black people in the South the basic skills they needed to survive and participate in American society. They were concerned both for the individuals who stood to benefit from their programs and for the fragile nature of the recently reunited United States that they believed would gain stability largely through an educated citizenry.31

Trustees and agents of these foundations crisscrossed the South by train and automobile gathering data for their developing programs. They sought out southern educators such as Jackson Davis of Virginia, who shared their vision of equal educational opportunities for whites and blacks in the South. They also hoped to engender change in white southern society as well. Donations from these funds usually were contingent upon the receiving agency (usually a local school board) raising like sums of money, matching funds in the modern parlance. A resolution of the trustees of the Slater Fund summed up the philosophy subscribed to by nearly all educational foundations of the period:

RESOLVED, that … in all cases where appropriations are made to schools, colleges, or institutions … it is particularly desirable to make such appropriations dependent upon a like or larger sum being raised for the same specific purpose by the parties interested.

Local white authorities thus had a vested interest in sponsoring new projects and, more importantly, in their continuation. Aid was often granted on a sliding scale, perhaps $500 the first three years, $250 annually for the next two years, and $100 for equipment after the five years. Foundations usually made these appropriations with the understanding that public school boards eventually would assume full financial responsibility for the programs. 32

Public Schools Come to Williamsburg

Williamsburg after the Civil War was not only long since past its colonial glory, it was also suffering as much of the South was from the after effects of the Civil War. It now gave the appearance of just one among many other small southern towns. The 12 town's principal employers were the College of William and Mary and a state mental hospital.

On December 2, 1870, Col. Robert H. Armistead, William H. E. Morecock and P. T. Powell (known then as the Trustees of the Free Schools of the City of Williamsburg) held the first school board meeting for Williamsburg. The first order of business was to ask Powell, clerk of the board, to take a census "of persons between the ages of five and twenty-one in this district." At its second meeting on January 17, 1871, the board ordered the clerk to post notices of the election of teachers "at such places in this City as he may deem best." The board appointed its chairman Robert Armistead a committee of one to draft rules and regulations for the free schools in the city.33 At a time when localities expected funds for teachers' salaries and other expenses to come from state moneys, the Williamsburg city council appropriated to the school board part of the money needed to pay teachers and rent the spaces in which classes were held.34

By 1900 the free schools of Williamsburg served 245 white children and 278 black children. The school board routinely gave short shrift to the black school. While minimal repairs to the school building, lists of teachers, and limited supplies were noted in school board minutes, when it came to special ceremonies for opening and closing the school year, starting a library, providing pictures for the walls and special equipment, books, and a piano, it was the white children that got the lion's share of school revenues.

African-American Students and Teachers

In addition to children of both races who resided in Williamsburg proper, black and white pupils from outside Williamsburg (mostly from the Jamestown District of James City County and the Bruton District of York County) attended schools in Williamsburg as early as the 1880s and probably earlier.

When Virginia localities began putting their publicly funded school systems in place, they faced an immediate need for teachers of both races. At first there were relatively few educated members of the black community to undertake teaching positions or to provide state-wide leadership for black public school teachers. By 1890, however, there were nearly as many black teachers as white in Williamsburg and James City County. One historian has judged it evidence of the great value placed on 13 education in the black community that a majority of black teachers in the Williamsburg area in the late nineteenth century were men.35

Early antipathy among white Virginians toward publicly funded education for every child coupled with a scarcity of normal schools to train and qualify teachers sometimes resulted in shortages of white teachers. School boards relied on a pool of "genteel ladies" in reduced circumstances after the war and disabled veterans who were not unwilling to undertake respectable employment in the public schools.36 Small private schools or private tutoring arrangements probably already occupied a number of these men and women.37

At its third meeting on January 27, 1871, the school board elected its first teacher, James W. Edloe, to teach at the "colored school of this City, no other person having regularly applied." Later, the board elected Mrs. Virginia T. F. Southall and Miss Lucy H. Hansford for the white school. Both had taught privately before they signed on with the public schools in Williamsburg. At that time, there were separate classes for white boys and girls. Southall taught the boys, Hansford the girls. This same practice was followed in the black school as soon as the school board hired more than one teacher for black students. That occurred in December 1874 with the appointment of Miss M. A. Bright.38

Teacher's salaries were not set in advance during the first three years of operation of the Williamsburg public schools,39 but Edloe, Southall, and Hansford were not to be paid more than twenty-five dollars each per month. School board minutes in December 1871 ordered that salary moneys be distributed equally among the three teachers in the Williamsburg schools.40 It was not long, however, before teachers at the black school received smaller salaries than their white counterparts. In 1873 the school board hired Charles S. Dod of Lexington to assume the position of principal teacher of the white school in Williamsburg (Southall resigned in 1872).41 In February 1874, 14 the board paid Dod seventy-five dollars out of a combination of city and state funds. Lucy Hansford, assistant teacher at the white school and James Edloe, principal teacher at the black school received only $37.30 each from city funds.

Serious disparity between the salaries of white and black teachers continued in one form or another into comparatively recent times. By September 1875 the pattern was established: Carter H. Harrison, principal teacher of the white school, had a salary of $500 per session, Lucy Hansford, the assistant teacher, $270. D. H. Bourbon, principal teacher at the black school, took home the same salary as Hansford ($270), and Pauline Hill, assistant teacher at the black school, only $100.42

Black Schools in Williamsburg, 1870-1924

Records of the public schools in Williamsburg suggest that the school board relied on improvised accommodations for public school students of both races for a number of years. Rented school rooms in private houses or other buildings were usually crowded, inadequately lit, poorly ventilated, and the furniture makeshift. The school board achieved a stable environment for a "white male school" in 1873 when it took over from the College of William and Mary the Matty School on the site of the old governor's palace, but difficulties with first one space and then another prompted school authorities to shift both the black school and white girls from pillar to post.

When James Edloe gathered his African-American students together on the first day of public school in Williamsburg, February 1, 1871, they met in an as yet unidentified room or building, the first of a number of spaces rented by the school board for the black school. Evidence suggests that they may have used a rented building converted to school use. In November 1871, the school board ordered "eight hundred feet of inch plank to be used for the colored school," probably to re-sheath the roof of its rented quarters.43 Among accounts paid by the school board in August 1873 was $24.91 "to W. S. Peachy Matty for M. J. Smead for Rent of col[ored] school house." Two subsequent references refer to a room rather than a building or house, perhaps an indication that the school had moved : On May 22, 1874 the board paid $72 to S. 15 Morse [or Moore] for "Rent of room for Col[ore]d School." The following July a school room rented from S. Morse for the black school again shows up in school board minutes. In December 1874 the school board hired an assistant teacher for the black school, after which the boys and girls met separately.44

Local records for the next several years yield few clues to the locations where classes for black children were held, but in 1883 the black school shifted its operations to Mt. Ararat Church on Francis Street. Church trustees charged the board $36 for a year's rent. The board asked Samuel Harris, a prominent African-American businessman in Williamsburg and a member of the school board, to oversee the transfer of school furniture from the old schoolhouse (wherever that was) to the church.45

For many years, the Williamsburg school board did not even consider the prospect of erecting a school building from the ground up. A chronic shortage of funds, uncertainty about which funds school boards could legally spend to build schools, and inexperience in design and construction of schools all contributed to the delay. In 1883 the school board appointed a committee to "Enquire what funds may be Legally used for the Purpose of Building School Houses."46

Perhaps because the white male school was reasonably well situated after 1873 in the old Matty School, the first school constructed at public expense by the local board would be for African-American children. In 1884, the board appointed one of its members to get a drawing and specifications for building a school house for the black school not to exceed $950 and appropriated that amount of money for the project. At about the same time, the board appropriated around $400 for necessary renovation and repair of the white school.47

Samuel Harris kept tabs on construction at the Francis Street site acquired for the black school. The property faced "82 feet on north of Francis Street & running back 16 108 feet between the lots of M. R. Harrell and J. H. Barlow bounded on the north by a public square." Specifications for the school called for a brick foundation and a building measuring 22 feet x 62 feet on the inside with "14 windows 10" x 14" glass 18 lights to the window in the main building," cloak room in each school room (probably two), platform for the teacher in each room, and roof covered with good quality "heart-shingles" painted red. The board authorized Harris, as "inspector of the colored school" to contract for fencing and outhouses for the school not to exceed $60 in value and to arrange for stoves and fuel for the school. It was probably early 1885 before the contractor turned the new building over to the board.48 Part of principal Arthur F. Tate's compensation from the school board included his living quarters in the school building.49

The next year, the board designated the schools School No. 1 (white) and School No. 2 (black). School No. 1 continued in the Matty School until the contract between the school board and the College expired in 1894. The school board then rented the western half (three rooms) of the Armistead house in the Green Hill section of town for white students.50 By 1897 a new building known as the Nicholson School (named for the street on which it faced) housed the white school.

In 1907, the board ordered that building that housed School No. 2 be moved from its Francis Street location to the corner of Nicholson and Botetourt streets. In 1920 the school board rented the "Colored Odd Fellows Hall" in Williamsburg "for school purposes," apparently for temporary additional space for the expanding black student population. At the same meeting, board members authorized an additional teacher for the black school if "we can get an additional room without increased rent."51

The Black Community Supports Educational Opportunity

The United States Supreme Court held in 1896 that as long as public facilities for blacks and whites were on a par, the fact that they were maintained separately for the races did not infringe the civil rights of either group. The ruling (to be overturned by the high court in the next century) provided a workable solution for southern whites, but in practice black and white schools in the South were far from "equal." In Virginia as 17 elsewhere, white people, wary of educating blacks at all, were reluctant to have states and localities bear the expense and thought funding should come from the federal government. Their resistance was based in part on the fact that a large percentage of African-Americans in Virginia and elsewhere in the South did not own land or other taxable property, the principal sources of revenue for public schools.52

From 1870 onwards the school board in Williamsburg had separate school facilities for black and white pupils, but white and black schools in Williamsburg did not share equally the resources available to the school board. Although not addressed outright in board minutes, budget figures demonstrate that black schools in Williamsburg were nearly always funded at fewer per student dollars than white schools.

By the first decade of the twentieth century, there were reasonably substantial school buildings for students of both races in Williamsburg, but the white Nicholson School got preferential treatment. The school board authorized the purchase of maps and charts, water coolers, a piano, library books and an encyclopedia, and pictures for the walls at the white school. Moreover, they enlarged the building and faculty, and as previously noted, paid the white staff better salaries. The board saw to it that the opening of the fall school session at the white school included an "educational rally," and contracts for teachers at the Nicholson School actually contained a clause guaranteeing an end-of-term ceremony.53

Meanwhile, the school board sometimes addressed the need for better equipment and improvements in the physical plant at School No. 2, but the black school was clearly a lower priority. The board authorized the purchase of a globe for School No. 2 in 1907 and moved the school building to a new location at the corner of Nicholson and Botetourt streets that same year. They bought window shades (like those at the Nicholson Street School) for the building and a teacher's desk in 1914. But the school board also defeated a move to employ a janitor for the school, and board members were often unwilling for the city to foot the whole bill for improvements.54

In the face of such inequities, black parents and teachers across the South volunteered time and money on their own initiative or raised money for specific projects when school boards asked them to do so.55 "Colored school leagues" formed by 18 parents, teachers, and other members of African-American communities coordinated fund-raising and other activities intended to upgrade educational facilities. Records of public schools in Williamsburg reveal the same initiative locally where the Williamsburg School Improvement League was active.

In 1906, when the school board withdrew janitorial services from the black school in Williamsburg, teachers and students took on the cleaning in addition to their administrative duties, lesson preparations, and studies. Moreover, the school board asked black parents to provide more than half the cost of a sewing machine for the school, half the price of a school library, and half the rental price when additional space was needed in 1914. School board members agreed to have the school interior painted in that year too, but only if the black school bought the paint. The board seemed ready in February 1915 to purchase a "cottage" from the College to house industrial arts classes for School No. 2. When instead the College donated the cottage to the city, the school board purchased a lot adjoining the black school for $300 to accommodate it, but they agreed that the building could be moved to the new location only "provided that the $200 now in the hands of the colored school league, be turned over [to] the Supt of Grounds and Buildings of this board." 56 At another time, black parents bought a vehicle and paid $1.35 per month to transport their children from the Grove area to school in Williamsburg.57 Parents and teachers also may have arranged opening and closing ceremonies to mark school sessions at the black school.

Young people in the African-American community could not have been unaware of the obvious favoritism shown by the board toward Nicholson School nor of the sacrifice of both their parents and teachers to improve their educational prospects. That awareness may have contributed to an incident on the streets of Williamsburg before the turn of the twentieth century. School children of both races evidently used the same path going to and from their respective schools (white school on Palace Green and black school on Francis Street). It was February 1895 when one Eli Brown was suspended from the black school for "unbecoming conduct in the street." Brown had refused to yield the pathway to white students returning home from school. When some of the white boys pushed Brown aside, a scuffle ensued. Questioned by the superintendent about his conduct, Brown stated that "he would die before he would 19 give the path to those boys."58 A local resident recalls that incidents such as this one caused the school board to stagger the opening and closing times at the black and white schools in order to minimize contact among students.59

James City County Training School, 1924-1940

The black school continued to be housed in the 1883 building moved in 1907 from Francis Street to the corner of Nicholson and Botetourt streets. A room or rooms in the Colored Odd Fellows Hall in Williamsburg provided additional classroom space by 1920.60

In early 1919, a letter from the Committee of the Improvement League of the black school to the school board asked the members to authorize a new school building for the black school. The League wrote that "they were ready to rase [sic] their portion of the money needed." After a discussion, the board referred the matter to the superintendent of school and the League to get together and formulate plans about size and costs.61 In March 1919, L. W. Wales, Jr. and Andrew Jones of the Improvement League appeared before the school board as advocates for the new school. On a motion the school board guaranteed a four-room school house provided the League first raised $1000 and placed the same in the hands of the board. Wales and Jones stated that they already had pledges of $767.50 as well as prospective buyers for the old school complex (main building and industrial cottage).62

In July, Wales again appeared before the school board to announce that the League had the $1000 in hand. He also pointed out to the board that the black community preferred a male principal for their school.63 In September of the same year, the board decided to secure a loan of not more than $5000 from the state Literary Fund to help finance the new black school. At the same meeting they noted that they intended to borrow about $15,000 from the Literary Fund and float a bond issue for 20 $30,000 in order to proceed with a new high school for white students to be constructed at the north end of Palace Green.64 Officials of the Literary Fund approved both loans late that same month.65

By 1922 the new black school still had not been built, although three lots on Nicholson Street had been purchased for it (the black school League later contributed $350 toward the purchase price). Andrew Jones and W. H. Hayes (principal of School No. 2) of the "colored school League" came before the school board on June 6 to pledge $2500 in addition to the $1200 already raised. Their reason was that they wanted a six room school plus "a room suitable for a training school" instead of the four room school house that the board had planned. The board "fully appreciated their requests, & promised to give them such a building as their finances would permit."66

The very next month, July 1922, the superintendent of James City County schools asked the Williamsburg school board to consider combining the "agricultural schools" (usually called "training schools") of James City County and Williamsburg to be located in Williamsburg but jointly operated by the city and county school boards.67

Establishment of county training schools usually came in response to several conditions: a need for a larger and better school to supplement elementary education provided in small rural schools, a demand for teachers better prepared for their jobs, a preference for offering agricultural and industrial training, and a willingness on the part of local officials to cooperate in securing support from a philanthropic organization. Assistance from the Slater Fund required that a training school be part of the local public schools, that there be an appropriation of at least $750 dollars for teachers' salaries from public funds (state, county, or district), and that grades extend at least through the eighth with two more years added as soon as possible. The length of school terms was also a concern of philanthropic organizations. The Slater fund required an eight-month school term if aid was to be forthcoming.68

21Schools usually did not carry the "training school" name unless they received Slater moneys. Officials of the school boards of both Williamsburg and James City County recognized a financial advantage in deeming School No. 2 on Nicholson Street a training school, as long as it was still in use. They would call the new facility the under development James City County Training School. The state supervisor of Negro education notified Principal Hayes in September 1922 of $500 from the Slater Fund for teachers' salaries "this year" and sent a course of study for "our Virginia training schools" which he hoped Principal Hayes would follow at the "new colored school." By October the state supervisor of Negro education informed the Williamsburg school board that the General Education Board (G.E.B.) had promised $200 to the "James City County Training School" for miscellaneous equipment for the current session (1922-3), clearly indicating that this name was applied to the old school because bids for erecting the new school were not taken until May 1923.69

The new James City County Training School (1924-1940) opened on Nicholson Street in Williamsburg not far from the old School No. 2. In the training school tradition, it was designed to prepare its students to become school teachers themselves, that is it offered professional training for students wishing to meet state teacher qualifications and agricultural courses particularly helpful to students from rural areas.70 The school took students from the first grade through the eleventh.71

Disparities that had existed all along between black and white school facilities in Williamsburg persisted in the 1920s and '30s. For instance, in 1931, the operating expenses for the James City County Training School and the new white Matthew Whaley School stood at about $1500 and $5470 respectively. At the black school there was a principal (salary, $1050), a vocational agricultural teacher ($1200), and eight other teachers to cover eleven grades ($525 to $650). Matthew Whaley on the other hand had a principal, Rawls Byrd, who was also the superintendent of schools ($2300), seven elementary teachers ($900 to $1900), eight high school teachers ($1110 to $2350), and five special teachers for art, physical education, music, industrial arts, and home economics ($900 to $1934). The school board, which nearly always met at Matthew Whaley, continued to give priority to "the school," meaning the white school.72

Further widening the funding gap was the fact that the College of William and Mary was closely involved in educating the white children in Williamsburg from 1873 22 onwards. Not only was the College entirely responsible for running the elementary grades for a number of years, it contributed sizable sums to the operating budgets of the white school.73 Public school teachers at the white school who agreed to supervise student teachers from William and Mary got a salary supplement from state money via the College. By the late 1930s Matthew Whaley's budget reached $38,338 ($22,503 of which came from the College). In that same year, $8115 was expended by the school board on the James City County Training School.74

PART II

BRUTON HEIGHTS SCHOOL, 1938-1968

Make Do or Start Over?

The James City County Training School, an early beneficiary of Rockefeller, Rosewald, Slater, and Jeanes foundations, served the African-American school population in the Williamsburg area for about sixteen years. Williamsburg's first black high school which also included the elementary grades, it was not only bursting at the seams by the late 1930s but in need of extensive repairs.

A local development that had already brought major changes to the Williamsburg community at large was to have profound consequences for public education, particularly black education, in the area. John D. Rockefeller, Jr.'s decision in 1926 to restore Williamsburg to its eighteenth-century appearance according to the vision of The Rev. W. A. R. Goodwin was well on the way to becoming a reality.75 And it was not long before a Rockefeller representative made contact with the school board in Williamsburg. As early as 1928, Goodwin initiated negotiations between the Williamsburg Holding Corporation76 and the board about acquiring the white high school and elementary school and the land on which they sat, the site of the eighteenth-century Governor's Palace.77

24The first recorded contact between the Williamsburg Holding Corporation and the school board regarding the black school came in June 1931. The Restoration offered the school board, without cost to the school, the use of an old frame building diagonally across the street from the James City County Training School. School officials converted it into a shop (industrial arts) building for the 1931-1932 school year. Two years later the Restoration notified the board that the "building used for manual training work at the colored school" had to be vacated at the end of the 1933 school term, because it was to be torn down shortly thereafter. The Restoration donated the lumber to the James City County Training School where it was used for roof repairs.78

These and other negotiations regarding public schools in Williamsburg made for frequent correspondence and personal contact between the superintendent of schools Rawls Byrd and other members of the school board and Vernon Geddy, resident director of the Williamsburg Holding Corporation. On June 23, 1935, Geddy took a seat on the school board.79

While the school board and city council juggled funds in the thirties to do little more than jerry-rig the dilapidated James City County Training School, a movement toward an improved educational plan for their children was once again afoot in the black community. A committee from the School League of the James City County Training School appeared before the school board on July 11, 1935, asking the board to repair the walls of the auditorium, paint the interior of the school, paint the home economics building, hire a music teacher, rearrange the rooms, fix up the basement of the school, paint the outside, and repair the sills of the building where needed.80 At their meeting on July 18, 1935, school board members recommended that a letter be directed to the city council describing the poor condition of the black school building. The letter also pointed out that certain repairs to heating and plumbing systems would be made before school opened in the Fall, whether or not the city had the funds to pay for them.81

25City council finally coughed up $700 in September for repairs to the roof and plumbing. Council also suggested that application to the Works Progress Administration might bring in funds for additional improvements at the James City County Training School.82 At about the same time the school board hired a music teacher for black students. In October 1935, they voted a ten dollar supplement to the music teachers' salary out of a small amount of money received in tuition from York County pupils. But budgetary shortfalls continued to delay critical repairs at the James City County Training School. When the school board presented its 1936 budget to the city council in late 1935, board members had agreed that the council "should be made to feel some share in the responsibility" for plastering and painting all woodwork at the school. The city council, however, refused to make a special appropriation of $1000 for the work.83

The subject of constructing a new school to replace the James City County Training School was not addressed head-on in the early 1930s, but at least as early as July 1933 (and again in February 1935) school board members recognized that the proximity of the school to the restored town could mean that the Restoration might decide to buy (and subsequently remove) the old building on Botetourt Street. By February 1936, the school board had begun to take a serious look at constructing a new building for black students. They appear to have supposed that they could undertake this project for about $25,000. At this early stage, school board members thought that the Restoration might agree to pay about $20,000 of this sum for the James City County Training School and grounds.84

The school board was not encouraged by a report from Raymond B. Long, director of the division of school buildings of the Virginia state department of education. His estimate of $45,000 for a new building seemed well beyond the city's and school board's resources, but the board was unwilling to abandon the idea altogether. Board members hoped to persuade James City County to provide some of the funds necessary to erect a new black school, if it planned to continue sending children from the county to school in Williamsburg. Even though some 40 percent of the enrollment 26 at the James City County Training School was made up of county children, the county was lukewarm about a joint project and made no commitments.85

In June 1936 the board asked Vernon Geddy to meet with a James City County official to point out that the county's then-current plan to add three rooms to one of the elementary school buildings in the county for county high school students would not be in the best interests of those pupils. At the same time, Williamsburg school superintendent Rawls Byrd reported that the Restoration had offered $10,000 cash and a new building site in exchange for the James City County Training School building and grounds. To its credit, the school board went on record in 1936 as opposed to continued "piece-meal repairs which they are convinced are neither economical nor efficient" should the city council ultimately decide to repair the old "unsanitary and inadequate" black school building instead of finding a way to finance a new school plant, by July 1936 estimated to cost around $60,000.86

With offer in hand of $10,000 and a piece of land from the Restoration, the idea of a new school building for African-American pupils in and around Williamsburg gained momentum. The city council and the school board began to take steps, halting at first, to secure funding for the project. The board approved an application to the Public Works Administration (P.W.A.) for $27,000 (45 percent of $60,000) at their meeting on July 27.87

But with the 1936-1937 school year bearing down upon them, school board members recommended that contracts be sent "to the Negro teachers of the past school year," since there was not time to do major repairs to the training school building, let alone build a new school before the fall session. In fact, that would be the tack taken for another year or more. The city council and the school board continued to weigh the merits of effecting major repairs to the old James City County Training School and constructing a brand new black school. Moreover, application for outside funding was a slow and tedious process. No word on the fate of the application to the P.W.A. filed by the school board prompted superintendent Byrd and the mayor of Williamsburg, Channing Hall, to send the city attorney to Washington to investigate in January 1937. He returned hopeful that the application would be successful, if they sent the P.W.A. additional information about the site of the new school, guarantees from city council to 27 furnish "their part" of the money, and assurances that the proposed school "is an agricultural high school."88

Other sources of funds were also available. The board approved about this time an application for state aid in erecting and equipping a home economics cottage for the black school ($800 toward a building costing $3000 and half the $700 cost of equipment).89 Byrd had also determined that 60 percent of the value of the proposed building and grounds could be borrowed from the Literary Fund of the State Department of Education. In view of these developments, board members advised that new feelers be put out to James City County to find out what part of the costs of a new black school the county could be expected to shoulder.90

Meanwhile, members of the "Negro school league" had not only pressed the school board to refurbish the James City County Training School, they now kept close tabs on plans for a new building. In the same month (February 1936) that the school board first broached the subject of a new school for black students, a committee from the league went to see Rawls Byrd. They pointedly asked that they be consulted before the board or the city took any steps to dispose of the present building or began construction of a new facility, and they strongly advised that the league be consulted about the location of a new building.91

Neither was the Restoration and its meaning for their community lost on the black citizenry of Williamsburg. Addressing themselves to Williamsburg Holding Corporation in 1937, the James City County Training School League explained their ideas for a comprehensive educational and community center for the African-American community in Williamsburg and nearby rural areas. The League's vision was clear:

We wish to let you know that, as Negro citizens we are interested in the Restoration Movement in the Yorktown, Jamestown, and Williamsburg area. We are interested in the movement because (1) colored people were among the earliest settlers in this area, (2) we have helped to build up and to preserve the Nation and stand willing to sacrifice again and again to uphold law, order, and peace, and (3) we desire our sections of these communities, wherever they might be, to harmonize with 28 the Restoration Movement. We are extremely anxious that the members of the city School Board, the County School Board, the Williamsburg Holding Corporation, and others who are responsible shall know that as Negroes we are in accord with the movement and stand ready to cooperate, and we hereby beg the interest of the above mentioned bodies toward us as a race in this monumental area.

The League had a plan in mind for a central school facility that would house students from the first grade through high school. They suggested the school serve as a community center for the black community as well. To quote the letter again:

That Negro schools be consolidated and that the high school be made such type as to care for the boys and girls within a radius of fifteen miles. We need a building of the modern colonial type with twelve classrooms for academic work, two classrooms for agriculture (or a small building outside), two classrooms for home economics, a cafeteria, library, office, auditorium and gymnasium combined, one large room for special meetings and for feeding special groups, adequate playground space, and inside lavatories including provisions for male and female teachers and janitor's supplies.Deferential in tone though this letter was, it nevertheless claimed the right to improved educational and community facilities: "We believe you appreciate the contributions colored people have made to Virginia's historical progress and prestige."92

Rawls Byrd read a letter from the League, possibly a copy of the one addressed to the Restoration, or one written along similar lines, to board members at their meeting on March 1, 1937.93 A direct answer to these communications do not appear to have been forthcoming from officials at either the Restoration, the city, or the school board. Conspicuous by absence, initiatives from the black community do not figure in later accounts of events leading up to development of Bruton Heights School.94 Still, Kenneth Chorley, president of the Williamsburg Holding Corporation later said that John D. Rockefeller, Jr. knew that the existing black school was badly in need of repair.95 Rockefeller contacts in the local black community were to prove fortuitous.

Development and Funding of Bruton Heights School

On February 10, 1938, almost exactly one year after the James City County Training School League wrote to the Williamsburg Holding Corporation and the Williamsburg school board, the city council asked the city manager to get yet another set of concrete comparative figures on the costs of building a new school for the black students and repairing the old James City County Training School on Nicholson Street. City officials brought Kenneth Chorley, president of the Williamsburg Holding Corporation, into this round of deliberations early. The council ordered Rawls Byrd, superintendent of schools, to get two sets of plans for a proposed school in March 1938; one set was earmarked for Chorley.96 The very next month, school board member Vernon Geddy, representing the Restoration at this meeting, told the school board that the company was very interested in improving "Negro education and living conditions for Negroes in Williamsburg and James City County." Geddy further stated that he believed the Restoration could be of help making plans for the future of education in these black communities by getting a survey made at no cost to the school systems.97 This suggestion apparently came directly from Rockefeller himself. He had recommended that Chorley approach the General Education Board "to see if a study could not be made and a full and complete program for Negroes developed with the new school as a center."98

A joint communiqué from the Williamsburg and James City County school boards on April 27, 1938, requested that "such organizations as they deemed proper to make a survey of existing educational facilities for Negroes [and] render to the two boards findings and recommendations for improving Negro education in these communities."99 Negotiations with the General Education Board were soon underway and put on the fast track. Not only was it a Rockefeller foundation, but associate director Jackson Davis, the Board's "eyes and ears" in the southern states since 1915 from his office in Richmond, had reason to remember Williamsburg.

Davis, a native Virginian and 1903 graduate of the College of William and Mary, had served as principal of the Nicholson School (white School No. 1) in Williamsburg in 30 the 1902-1903 school year.100 By 1905 he had assumed the post of superintendent of Henrico County schools. His duties in that job took him into both black and white public schools. What he saw in the black schools propelled him into a lifelong commitment to meeting the educational needs of the black community. In 1908 he had become Virginia's first state agent for Negro schools.101 Moreover, the public schools in Williamsburg were not unknown to the General Education Board itself. The Board had awarded $200 to the black school for the 1922-1923 school year. In 1925, a year after the James City County Training School opened, disbursements for operation of the school included $300 from the General Education Board.102

With assistance and participation from Davis, a committee made up of school superintendents from Williamsburg, James City County, and York County; various state agencies including the state supervisor of Negro Education and supervisor of School Buildings; several officials from Hampton Institute including the director; the state supervisor of agricultural education, and the state supervisor of home economics education set about gathering data about Williamsburg and its black citizenry. Davis arrived in Williamsburg on Saturday, May 7, 1938, and the survey began in earnest shortly thereafter.103

Davis and the committee prepared a report in just ten days in May 1938. It analyzed economic, educational, occupational, and public health conditions in the black community in Williamsburg. The resulting "Proposed Educational Program for the Occupational and Social Needs of Negroes in the Williamsburg Area" (Appendix I) called for an educational program that not only raised the standards for instruction and faculty qualifications but called for a modern school plant and twelve grades for black students.

31The cost of a building required to house students from the first grade to the eleventh and meet the needs outlined in the report now came to $245,000 ($210,000 for the building and $35,000 for equipment), more than four times the amount originally proposed by the school board. It was clear that the city alone could not finance a project of that size. Only 200 students at the new school would be from Williamsburg itself; the other 500 pupils in the expanded school program would come from the two adjoining counties. Nevertheless, the school boards of James City and York counties declared themselves unable to make contributions for capital outlay, all the while agreeing to work with the Williamsburg school board toward the proposed program "as an ideal" as rapidly as possible.104

Ultimately, a combination of borrowed funds and outright grants and gifts provided the money for the proposed school that Jackson Davis called "the best plan of Negro education which has ever been developed in this country up to the present time; and, if the program should be put into effect, it would be the only place in the country to have such a program."105 Potential sources of funds included the Public Works Administration, the Virginia State Literary Fund, the sale of the James City County Training School property, a city bond issue, and the Rockefeller family.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. authorized Chorley to reaffirm to the city council that the Williamsburg Holding Corporation was prepared to buy the James City County Training School buildings and grounds for $10,000 plus land for a new school. After this announcement, mayor Channing Hall of Williamsburg met privately with Chorley in the hope that the Restoration could be persuaded to pay more for the old school building and grounds or could find some other way to assist the city in securing a new building. Chorley had no doubt that the council "had in the back of their minds Mrs. Rockefeller's interest in the Negroes."106

Williamsburg had applied to the P.W.A. for a grant to cover about 45 percent of the $60,000 they had planned to spend; the agency awarded $27,000 to the city in the summer of 1938. After the city adopted the revised plan for the black school, Jackson Davis wrote directly to the P.W.A. asking that the application be increased to a $210,000 project. Byrd read a copy of Davis's letter to the school board on May 30, 1938 together with a telegram from the regional director of the P.W.A. in which he advised local school officials to file a new application with plans and specifications for the proposed building. The school board adopted a resolution authorizing Rawls Byrd 32 to file an amended application to the P.W.A. immediately. If approved, about $95,000 in federal funds would be forthcoming.107

The city council and the school board continued to have grave misgivings about whether or not Williamsburg could afford this expanded school project even with a sizable infusion of federal money. Rawls Byrd wrote to Jackson Davis on July 9, 1938 that in order for the school board and the city council to continue to work for the revised school plan, they needed some assurance that additional funding was in the offing to help the city chip away at $115,000 that a grant from the P.W.A. would not cover.108

Even if $100,000 could be borrowed from the state Literary Fund, the loan had be paid off at 4 percent interest in thirty years. That together with the bond issue the city appeared likely to pass for part of the needed funds added up to a debt load the city was unlikely to be able to sustain. Increased operating costs of the larger school plant were another serious concern. The county boards agreed to pay Williamsburg a sum equal to the per capita expenditures the counties currently spent to run their soon-to-be closed rural schools, but these funds, figured at pre-Bruton Heights School levels, were not likely to make up the nearly $15,000 per year in increased operating expenses Byrd anticipated.109

Byrd looked to Davis for "encouraging information" that the General Education Board would help fund the project since it had underwritten the survey of educational needs in the African-American community in and around Williamsburg and since Davis himself had participated in that process.110 Byrd was not to be disappointed. Davis told Kenneth Chorley that the General Education Board did not appropriate funds for capital expenditures for secondary schools, but he recommended that the G.E.B. make an annual appropriation for perhaps five years to cover increased operating costs. The G.E.B. also decided to provide $35,000 for equipment and furnishings for the new school.111

Meanwhile, Chorley broached the subject of a gift to the city with John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Chorley realized that the expanded school program as it now stood 33 was "a much larger one than Mrs. Rockefeller ever had in mind when she expressed an interest in the Negro problem in Williamsburg," but wondered if Rockefeller thought it was "something she might possibly like to consider."112 Although a public announcement was not made for some time, Chorley knew in August 1938 that Mrs. Rockefeller was prepared to contribute $50,000 toward construction of the new black school in Williamsburg.113

Inquiries from Rawls Byrd and others to officials in Washington generally sounded promising, but by September 1938 there was still no word on the fate of Williamsburg's amended application to the Public Works Administration. At that point, Chorley wrote to Harold L. Ickes, secretary of the interior. Before mentioning the P.W.A. application to Ickes, Chorley brought him up to date on "the Negro school project" and confidentially divulged Mrs. Rockefeller's pledge of $50,000. Chorley cannily told Ickes that he while he doubted that the application would have come to Ickes's personal attention, he (Chorley) felt justified in writing to him about it because of Ickes's "interest in the negro and education." Chorley went on the say that "if these educators [in charge of the survey funded by the G.E.B.] are correct that this is the most up to date program for negro education in this country and that it may have a possibility of influencing negro education throughout the South, it becomes much more important than simply another negro school."114

Ickes responded to Chorley's letter in two days. He disclosed that the amended application was under consideration and that Chorley's comments about the project's potential influence on black education in the South "have been noted." Ickes went on to say that Mrs. Rockefeller's offer to aid the city in financing its share of the costs and Chorley's own interest in the school "will not be overlooked."115 Less than a week later, on September 23, the Public Works Administration announced that it had approved a grant of $94,500 to the city of Williamsburg for what was to become Bruton Heights School.116

In December 1938, the Williamsburg school board received a letter from Abby Aldrich Rockefeller in which she officially offered $50,000 toward the proposed black school. Board members proposed that the letter be published in the newspaper. Local 34 newspapers carried the story on December 16.117 Later that month the General Education Board pledged $35,000 (increased to $77,000 in 1939) toward equipment and an operating subsidy.118 True to form, the African-American community promised raise about a thousand dollars toward the cost of landscaping.

The New School Plant Takes Shape

Having secured most of the funding for the new black school, the school board and city council set about locating a suitable site in October and November 1938. At first, land belonging to John D. Rockefeller on York Street between the city limits and Quarterpath Road was considered. A York Street resident submitted a petition to the city council requesting that "The new colored school not be located where designated."119 When it became apparent that a tract large enough to accommodate a shop building and agricultural plots would be needed, the city council took two or three other locations under consideration. A large parcel in an area called Bruton Heights soon emerged as the most promising. There were objections from white residents on Capitol Landing Road whose property would back up to school grounds, and several members of the black community objected to it as well.120

In December 1938, the mayor of Williamsburg presented to the council a petition from a large number of black citizens "asking that the location of the new school be left to the discretion of the City School Board."121 Soon after, Kenneth Chorley wrote to Mrs. Rockefeller that Vernon Geddy had mediated the differences by "attending the meeting of negroes, which was very representative of the negro population at Williamsburg, at which he spoke for an hour and a half" and in interviewing the white residents of Capitol Landing Road. At its next meeting, council unanimously accepted the site on the north side of the railroad track, let contracts, and on December 15, 1938, broke ground.122 Williamsburg Restoration, Inc. bought the old James City County Training School for $10,000 and deeded the thirty-acre site in Bruton Heights to the school board.

35The "Proposed Educational Program" incorporated a number of ideas remarkably similar to the broad outline of a school and community center put forward by the James City County Training School League in 1937. The building would be large enough to accommodate an initial enrollment from Williamsburg, the Bruton District of York County, and the Jamestown District of James City County(somewhere in the neighborhood of 700 pupils. The plan called for several county elementary schools in James City County to close and those students to come into Bruton Heights. High school students from the Bruton District of York would also be part of the newly consolidated student body.

Geddy's and school superintendent Rawls Byrd's research on school construction took them to Richmond where they got estimates from a private architectural firm and met with Fred Alexander, director of Negro education in Virginia; Raymond Long, director of the department of architecture in the state board of education; Dr. Van Oot, supervisor of trades and industrial education; and others. They visited an industrial school in Hershey, Pennsylvania, funded by Milton S. Hershey; they went to a black industrial and agricultural school in Powhatan County, Virginia "which had the finest equipment of any school, either colored or white, in Virginia" at the time; and they also visited a Catholic school. These meetings and a conversation with Jackson Davis persuaded Geddy and others that Raymond Long "was by far the best qualified man in the State to prepare these plans" and that the advice of Long and Alexander was sound.123

The school complex was designed with a main building for eighteen classrooms, a library, gym, auditorium, cafeteria, clinic, and music room. Plans also called for an industrial arts building with several shops and classrooms. It would also house the "horticultural and agricultural divisions" which would use the surrounding grounds to teach farming and gardening techniques. A home economics building, or cottage as it came to be known, included a living room, dining room, bedroom, bath, kitchen, laundry, demonstration kitchen, and classrooms where students of both sexes would be taught hygiene, sanitation, meal planning, and how to care for a home.124 The school was also intended to be an educational center for African-Americans within a five-mile radius of Williamsburg. Evening adult education classes and clinics would be held in the building.125