The Williamsburg Market House : Where's the Beef?

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series -245

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

The Williamsburg Market House: Where's the Beef?

A Report for the Educational Planning Group

Architectural Research Department Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

March, 1986

This research was funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, "Planning for the Interpretive Programs for the Courthouse of 1770" (GM-21713-83).

List of Illustrations

| 1. | 1781 map of Williamsburg and vicinity |

| 2. | Detail of the Frenchman's Map around the Powder Magazine |

| 3. | Archaeological Foundations, Block 12 |

| 4. | Market House, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire |

| 5. | Plan of the 18th century Market House, Fredericksburg |

| 6. | Market House, Charleston, Maryland |

| 7. | Plan and elevation, Fredericksburg Market House |

| 8. | Market House, Louisville, Georgia |

| 9. | Market House, Newport, Rhode Island |

| 10. | Unidentified English Market House |

The Williamsburg Market House

Introduction

The southern side of market square in Williamsburg was a far more active and congested place in the eighteenth century than is now apparent from its present interpretation. The vast green space was less of an armed camp centering on the Powder Magazine and Guard House than it was the economic and judicial forum of the city and county. The routine of monthly county and borough courts insured that the space was thronged with crowds of participants and spectators. The weekly or semiweekly markets that finally became established by mid-century, brought yet more townsmen and outsiders to the heart of the borough where they purchased goods, exchanged news and gossip, and helped themselves to the food and beverages dispensed at nearby taverns. In the midst of these activities stood two important structures. On the north side of the public square was the borough and county courthouse, erected in 1770; on the south side was a wooden market house built in the 1750s. Although the brick courthouse has survived many vicissitudes, the market house has disappeared. The purpose of this report is to briefly review the historical, archaeological, and architectural information about this structure so that we can begin to put our thoughts in order about the possibility of its reconstruction.

Markets

Fundamental to the very existence of urban life is the role of the town as a center of exchange. The most basic function and one integral to towns of a certain size and economic diversity is the marketing of goods, particularly foodstuffs such as meat, poultry, cheese, eggs, butter, and vegetables. In eighteenth-century England and America, towns held markets once or twice a week in large open spaces in or near the center of the town. Most larger towns started off with a single open market, but if they prospered almost invariably ended up with several. This main market place sometimes grew smaller because stalls and temporary stands developed into permanent shops and houses or its edges were encroached upon by those who found it advantageous to be near the market. This occurred in Williamsburg where shops and taverns were built on public property. Elsewhere, in places like Norfolk, the market was enlarged to handle increased trade and divided into separate sections for the selling of fish, meat, livestock, and grain.

The local market was not a free-wheeling, open-ended emporium of petty capitalists, although there was a strong push to make it so in many English and American towns in the eighteenth century, rather it was a highly-regulated system watched over by the clerk of the market in concert with other 3 corporate officials. The right to hold a market was a sign of a town's independence and a jealously guarded privilege. Markets also provided an important source of corporate income from the rent of market stalls and an excise on certain sales. The corporation continuously intervened in the economic affairs of its jurisdiction in order to play the role of the honest broker between the merchants and the populous at large. Its chief aim was the maintenance of civic harmony but it had to steer a delicate course between over regulation which might threaten economic prosperity and a laissez-faire approach which might provoke unrest over the high price of basic commodities.

Trade in eighteenth-century market towns in Virginia took a variety of forms. At the heart of any town's prosperity was market day where tradesmen and itinerant higglers retailed their wares in the open market place. The principal goods bought and sold in the semiweekly markets consisted mainly of perishable foodstuffs and a few household items. Carts and wagons filled with provisions crowded into the open spaces in the early dawn hours each market day. Country people coming into town along with local hucksters set up movable wooden stalls and other temporary fixtures which provided a cheap and flexible venue for their produce. In market towns such as Williamsburg, Fredericksburg, Leesburg, and Norfolk, corporate officials, ambitious to attract trade, erected one and two-story market houses where sheltered stalls could be rented to certain vendors. Butchers were among the most common renters of the covered market house stalls since they needed shade to protect their meat from rapid spoilation and required spikes and hooks to support the 4 weight of hanging sides of beef and strands of game.

Where a sizeable portion of the population could not produce its own foodstuffs or have direct access to local farms, meat and vegetable markets tended to flourish. Such was the case of the port town of Norfolk where the market was well-stocked and well-regulated. In contrast, the market in Williamsburg was, at best, indifferently provisioned. Many of the town's residents chose to produce their own food on surrounding farms. In 1764 Robert Carter reluctantly decided to follow the example of his neighbors and bought a farm so that he could have "the articles to be obtained in good markets."1 In circumventing the public market, Carter well understood that he was contributing to its retardation. A few years later, the pseudonymous Timothy Telltruth bitterly complained to the Virginia Gazette about the quality of the goods sold in the Williamsburg market. His venomous pen excoriated the town's butchers who exacted exorbitant rates for meat "not fit to eat." Left hanging in the market house for long hours by neglectful vendors, sides of beef nearly spoiled. Bakers too, were no friend of the consumer. They used such unwholesome flour when they baked, that the bread they offered for sale was "very prejudicial to the health of those who eat it." It was a sellers market, especially during public times when the population of the capital swelled. If the 5 market was ever to emulate the well provisioned and regulated one in Norfolk, Telltruth believed that the magistrates needed to step in and straighten out the fishy business on market square. If it meant heavy fines for butchers and bakers or even the pillory, then all for the better.2

History of the Williamsburg Market House

Left hanging in the air along with the many sides of spoiled beef are many questions about the market house that was such an integral part of the economic activities on market square. The destruction of the records of the Williamsburg Common Hall has made it impossible to establish any detailed record or description of the market houses which stood on the south side of market square in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. This obliteration of the records may partially explain why so little interest has been expressed in the past by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in the reconstruction of the early market house.3 Although there is 6 little documentary material, there still remains the possibility that archaeological investigation of certain sections of Block 12 will reveal evidence for the precise location, configuration, and details of that market house.

What little is known of the history of the market place illustrates the great contrast that can often be found between intentions and reality. Williamsburg's small population and its easy access to surrounding farmland worked against the construction of a market house in the first years of the town's existence. The 1699 act which transferred the capital from Jamestown to Williamsburg empowered the governor to grant to the city the right to hold a market. Implicit in the act was the desire for the new capital to develop into a flourishing center of trade, something that Jamestown had never been able to do. In 7 a sense those who backed the move to Williamsburg hoped that it would take on many of the same characteristics of a provincial English town, among which include a well-stocked market place. With this in mind, the trustees of the town were given leave in 1705 to hold such markets as they thought appropriate and to "enlarge the market-place" if the need arose.4 Despite this early attention, it was difficult to get the Williamsburg market going. Governor Spotswood recognized this in 1710 when he observed the problems caused by the absence of a regular market, especially during public gatherings when the population of the town increased sizably. No doubt, like many other inhabitants, the governor favored the creation of weekly markets and worked hard to use his influence to remedy the matter.5 The next year he prompted the council to discuss the issue with the town trustees and in 1713 requested the House of Burgesses to help give some assistance towards building a market house but nothing seems to have been done.6 In 1720 the inhabitants may have enjoyed more regular markets but still faced great inconveniences 8 for "the want of a Market house."7

It's uncertain just how long Williamsburg went without a market house. There may have been one or two wooden structures on market square before the 1750s. Its just as likely that the building erected in 1757 may have been the first and only colonial market house. In April of that year the building committee appointed by the Common Hall met one evening to let the construction of a wooden market house. Although there is no evidence to confirm the actual construction of the market house in 1757, it is certain that some type of structure was standing on the south side of market square by the 1760s. In January 1764 an act of assembly authorized the city to raise what sums of money it needed to repair the market house and other public buildings when it became necessary to do so.8 A few years later Timothy Telltruth lodged his complaint about the beef left hanging in the market. In 1770 some inhabitants petitioned the House of Burgesses to convert the abandoned guard house on the square into a market house. Either the old wooden market house had been pulled down or more space was needed for marketing goods and the guard house was seen as a cheap means of meeting that demand.9 Following the Revolution and removal of the state 9 government, the market and presumably the market house were still functioning. An advertisement in the newspaper mentions a store near the market place and a traveler reported that meat and other provisions sold at a very cheap rate.10 The later fate of the market house, however, is much like its origins, unknown. By the middle of the 1790s, it may have been pulled down since the powder magazine had become the principal and perhaps only market house on the square.11 The magazine may have continued in this capacity until the early 1830s when a new market house was erected on the south side of market square.12

Archaeological Evidence of the Williamsburg Market House

A 1781 map of Williamsburg depicts the market house on the south side of the Duke of Gloucester Street, just east of the courthouse (Fig.1). Unfortunately, the scale of the map is teasingly too small to be able to provide the precise location of the building. The Frenchman's Map of the same period confirms

Fig. 1. Samuel DeWitt, "From Allen's Ordinary through Williamsburg to York," 1781. Copy of map, CWF Library.

11

the presence of at least three small structures east of the Powder Magazine on market square (Fig. 2) . The Rochambeau Map too, identifies three buildings in approximately the same location. Presumably, one of these three unidentified rectangular structures, which stood in a cluster in the northeast corner of the public square, was the market house. No other cartographic evidence appears until the early twentieth century when insurance maps show much of the area around the magazine cluttered with buildings ranging from a Greek Revival church to a frame garage. Clearance of those buildings in the early 1930s was followed by archaeological investigations.13

Fig. 1. Samuel DeWitt, "From Allen's Ordinary through Williamsburg to York," 1781. Copy of map, CWF Library.

11

the presence of at least three small structures east of the Powder Magazine on market square (Fig. 2) . The Rochambeau Map too, identifies three buildings in approximately the same location. Presumably, one of these three unidentified rectangular structures, which stood in a cluster in the northeast corner of the public square, was the market house. No other cartographic evidence appears until the early twentieth century when insurance maps show much of the area around the magazine cluttered with buildings ranging from a Greek Revival church to a frame garage. Clearance of those buildings in the early 1930s was followed by archaeological investigations.13

In 1934 and again in 1948, the area east of the Powder Magazine was excavated in the vigorous manner characteristic of early archaeological endeavors in Williamsburg. Cross-trenching revealed the foundations of a number of unknown eighteenth and early nineteenth-century structures (Fig. 3). The largest remains were those of a 40 by 60 foot building (Structure G), which stood close to the Duke of Gloucester Street, just northeast of the Magazine wall. The cryptic notes of the 1934 archaeological map mentions that the brickwork uncovered there

12

Fig. 2. Detail of market square, Williamsburg, c. 1782. Frenchman's Map.

13

Fig. 2. Detail of market square, Williamsburg, c. 1782. Frenchman's Map.

13

Fig. 3. Archaeological Features, Block 12. From a report by Patricia Samford, "Archaeological Briefing and Testing Plan; Block 12, Powder Magazine," CWF Office of Excavation and Conservation, 1985.

14

appeared to be post-colonial in character.14 Given the size and prominent location on market square, the building may have been the market house erected shortly before 1835, or possibly, some other unknown civic structure.15 At the southern edge of the 1934 excavation area, archaeologists discovered the foundations of a building which had a curious cruciform plan (Structure E). Measuring approximately 63 by 23 feet with two truncated and unevenly-sized, central projections, the Flemish bond brickwork had the "general character and appearance…of colonial workmanship."16 The unusual form of the building have led many to believe that it might have served as the 1715 James City County courthouse or the much later, early nineteenth-century county clerk's office which was demolished by federal troops in 1862.17 However, if all other evidence is to be believed, then the early county courthouse stood on the south side of Francis Street on the site of the Nicholas-Tyler House. The configuration of the plan may have some similarities to T-shaped courthouses in Virginia but its proportions are unlike any other. It would have been difficult to fit courtroom and jury rooms in the plan without severely altering known dimensional limits. An

15

alternative function suggested for Structure E is that it served as a market house. Markets with cruciform plans existed in England and America in the eighteenth century (Fig. 4). The dimensions of the Williamsburg structure nearly match those of the two-story brick market house built in Fredericksburg in the third quarter of the eighteenth century (Fig. 5) . However, there are two arguments against this interpretation. The 1781 map shows the market house distinctly located next to the Duke of Gloucester Street, nowhere near the lightly outlined Francis Street. The Frenchman's Map depicts no buildings near the position of Structure E which suggests that it was either already gone or yet to be built when the map of the town was made. Its location on the edge of the market square rather than in the center also tends to argue for some other function for the building.

Fig. 3. Archaeological Features, Block 12. From a report by Patricia Samford, "Archaeological Briefing and Testing Plan; Block 12, Powder Magazine," CWF Office of Excavation and Conservation, 1985.

14

appeared to be post-colonial in character.14 Given the size and prominent location on market square, the building may have been the market house erected shortly before 1835, or possibly, some other unknown civic structure.15 At the southern edge of the 1934 excavation area, archaeologists discovered the foundations of a building which had a curious cruciform plan (Structure E). Measuring approximately 63 by 23 feet with two truncated and unevenly-sized, central projections, the Flemish bond brickwork had the "general character and appearance…of colonial workmanship."16 The unusual form of the building have led many to believe that it might have served as the 1715 James City County courthouse or the much later, early nineteenth-century county clerk's office which was demolished by federal troops in 1862.17 However, if all other evidence is to be believed, then the early county courthouse stood on the south side of Francis Street on the site of the Nicholas-Tyler House. The configuration of the plan may have some similarities to T-shaped courthouses in Virginia but its proportions are unlike any other. It would have been difficult to fit courtroom and jury rooms in the plan without severely altering known dimensional limits. An

15

alternative function suggested for Structure E is that it served as a market house. Markets with cruciform plans existed in England and America in the eighteenth century (Fig. 4). The dimensions of the Williamsburg structure nearly match those of the two-story brick market house built in Fredericksburg in the third quarter of the eighteenth century (Fig. 5) . However, there are two arguments against this interpretation. The 1781 map shows the market house distinctly located next to the Duke of Gloucester Street, nowhere near the lightly outlined Francis Street. The Frenchman's Map depicts no buildings near the position of Structure E which suggests that it was either already gone or yet to be built when the map of the town was made. Its location on the edge of the market square rather than in the center also tends to argue for some other function for the building.

The fragmentary remains of three smaller structures just east of the Magazine wall are the most likely choices for market house. The spatial arrangement of these three buildings to each other and the Magazine is similar to that illustrated in the Frenchman's Map. In 1948 a second archaeological survey of Block 12 revealed for the first time two of the three enigmatic buildings. Too little of the easternmost building (Structure I) was uncovered to determine its size and configuration. Only one wall of brick bats and shell mortar running in an east-west direction was discovered and provided no clues to its original

16

Fig. 4. Market House, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, 1761. R. Adam, Architect.

17

Fig. 4. Market House, High Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, 1761. R. Adam, Architect.

17

Fig. 5. c. 1790 plan of the Market House, Fredericksburg, Virginia, Original in Loose Papers, Fredericksburg Courthouse.

18

function or date of construction in the colonial period.18 The remains of another building were found further south. Structure F, a rectangular building with a gable-end chimney, appeared to archaeologists to have been built in two stages during the colonial period. Not long after the building was excavated, work began on the construction of the present guard house over the first period foundations, although there was very little evidence for its appearance or location.19

Fig. 5. c. 1790 plan of the Market House, Fredericksburg, Virginia, Original in Loose Papers, Fredericksburg Courthouse.

18

function or date of construction in the colonial period.18 The remains of another building were found further south. Structure F, a rectangular building with a gable-end chimney, appeared to archaeologists to have been built in two stages during the colonial period. Not long after the building was excavated, work began on the construction of the present guard house over the first period foundations, although there was very little evidence for its appearance or location.19

The last substantial structure found on the site was discovered in the 1934 excavations just north of Structure F (the so-called guard house). The fragmentary nature of the foundations made it difficult to determine the precise dimensions of the building (Structure H). It was a little over 19 feet wide and at least 29 feet long and perhaps more. Although much of the brickwork had been robbed, that which had survived was "undoubtedly of colonial origin with oyster shell mortar of eighteenth century coloring & aggregate."20 The configuration and central location of these foundations argue strongly for Structure H as the c. 1757 market house. Its 19 relatively modest dimensions (approximately 19 by 30 feet) are similar in scale to other market houses in Chesapeake towns. According to specifications, the 1736 Norfolk market house was 30 by 15 feet and the 1752 building in Annapolis was slightly larger at 40 by 20 feet.21 The proximity of Structure H to the Magazine, the Duke of Gloucester Street, and Structures I and F strongly favors its interpretation as the market house. Only a new archaeological investigation of this building and its neighbors will help resolve questions of their origins and functions.

Market House Architecture

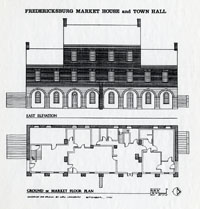

Eighteenth-century market houses followed certain standard design criteria. Foremost, they were to be as open as possible to allow for ventilation. A well-ventilated building helped preserve meat and produce and drew off the malodorous smells of overripe vegetables and decaying flesh. Most people also believed that stagnant or bad air, "malaria," caused a variety of illnesses. Added to this concern for sanitation was the desire to have a structure which would provide as much open space as possible for the exposure of goods to public view. No vendor wanted a stall stuck in a dark corner where few customers 20 would venture. To accommodate these concerns, market houses were built to stand invitingly open on columns, posts, or arcades (Fig. 6). The market houses in Norfolk, Annapolis, and Portsmouth (late eighteenth century) were supported by large wooden posts.22 Some buildings were erected to house a number of civic functions with the market on the open ground floor and courtrooms, meeting halls, or assembly rooms above stairs. Like the two early market houses in Fredericksburg, these two-story market halls were inevitably of masonry construction with the market floor accentuated by a brick or stone arcade (Fig. 7). Walls in the smaller, one-story market houses were either entirely absent or merely served to fill the small space between oversized doors and gates. The gaps between the six-foot wide doors of the Annapolis market house were enclosed with red-painted weatherboards.23

In order for every vendor to have a favorable venue to sell his goods, market houses were generally long and narrow so that few stalls would be out of public view or inadequately ventilated. Having a stall along the outer edge of the market house also made it easier for vendors to load and unload their goods from carts and wagons. In Norfolk and Annapolis, the early markets were twice as long as they were wide as may be the case

21

Fig. 6. Market House, Charleston, Maryland. Drawing by B.H. Latrobe, 1813. From Edward Carter, John Van Horne, and Charles Brownell, eds., Latrobe's View of America, New Haven, 1985.

22

Fig. 6. Market House, Charleston, Maryland. Drawing by B.H. Latrobe, 1813. From Edward Carter, John Van Horne, and Charles Brownell, eds., Latrobe's View of America, New Haven, 1985.

22

Fig. 7. Fredericksburg Market House and Town Hall, 1814.

23

in Williamsburg as well. As the success of various markets grew, market houses were either expanded or built anew with lengths sometimes measuring more than three or four times the width of the building. The lower floor of the 1814 Fredericksburg Market House and Town Hall measures 97 feet by 33 feet (Fig. 7) while the Norfolk market house dating from the same period was approximately 120 by 22 feet.24 Such long shed-like structures were commonplace in the larger seaports such as Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Fig. 7. Fredericksburg Market House and Town Hall, 1814.

23

in Williamsburg as well. As the success of various markets grew, market houses were either expanded or built anew with lengths sometimes measuring more than three or four times the width of the building. The lower floor of the 1814 Fredericksburg Market House and Town Hall measures 97 feet by 33 feet (Fig. 7) while the Norfolk market house dating from the same period was approximately 120 by 22 feet.24 Such long shed-like structures were commonplace in the larger seaports such as Philadelphia, Boston, and Charleston in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

A conspicuous feature on many market houses was the long overhanging eaves (Fig. 8). Both the Norfolk and Annapolis market houses had six foot "oversets" on each sides while the eaves on the 1797 market in Charleston extended yet another foot.25 These broad eaves provided additional shaded space for vendors and customers and allowed for stalls to be set up in front of the raised platform of the market house. For butchers, meats could be placed on the hooks of market posts behind them as a sort of advertisement while they set up their chopping blocks and trestle tables down on the ground. The large hooks driven into the stone blocks which still survive in the arcade floor of

24

Fig. 8. Market House, Louisville, Georgia. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HABS GA 82-Louvi 1-2.

the Fredericksburg market house and the early nineteenth-century illustration of the Newport, Rhode Island market house suggest

that such arrangements were commonplace (Figs. 9 & 10).

Fig. 8. Market House, Louisville, Georgia. From Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, HABS GA 82-Louvi 1-2.

the Fredericksburg market house and the early nineteenth-century illustration of the Newport, Rhode Island market house suggest

that such arrangements were commonplace (Figs. 9 & 10).

Typical of market house architecture as well was the paving of the raised market floor with stone, bricks, and tiles. Recent excavations of the eighteenth-century market house in Fredericksburg shows that the building had a brick floor as did its early nineteenth-century replacement.26 Perhaps with an eye towards cleanliness and cleaning, most of these paved floors stood one or two steps above the ground. The Norfolk market was three bricks above the ground, the one in Annapolis one foot, and the 1797 Charleston market 16 inches.27

The Williamsburg Market House: Architecture and Interpretation

Based on historical and archaeological evidence, it appears that the market house erected in Williamsburg in the late 1750s was a relatively simple wooden building raised on brick foundations. In all probability, the building had a shallow hipped roof with overhanging eaves, supported by four or five pairs of sizeable (12" by 12" for example) wooden posts set at

26

Fig. 9. Market House, Newport, Rhode Island, 1762. An 1831 engraving showing meat hanging from a pole in the left front arch. From The West Broadway Neighborhood Newport, Rhode Island, Providence, 1977.

27

Fig. 9. Market House, Newport, Rhode Island, 1762. An 1831 engraving showing meat hanging from a pole in the left front arch. From The West Broadway Neighborhood Newport, Rhode Island, Providence, 1977.

27

Fig. 10. Unidentified English Market House. From Country Life, August 16, 1984.

28

regular intervals (8 to 10 feet). The sides of the building may have been enclosed with weatherboarding, interspersed with a number of oversized doors which would be thrown open during each market day. Alternatively, if there was no desire to shut the building up when it was not in use or to enclose it during the winter months, then the market may have had no walls. Inside, stalls, which consisted of moveable or built-in tables, were set at regular intervals on the brick-covered floor. Overhead were a series of hooks, poles, and spikes for the hanging of goods.

Fig. 10. Unidentified English Market House. From Country Life, August 16, 1984.

28

regular intervals (8 to 10 feet). The sides of the building may have been enclosed with weatherboarding, interspersed with a number of oversized doors which would be thrown open during each market day. Alternatively, if there was no desire to shut the building up when it was not in use or to enclose it during the winter months, then the market may have had no walls. Inside, stalls, which consisted of moveable or built-in tables, were set at regular intervals on the brick-covered floor. Overhead were a series of hooks, poles, and spikes for the hanging of goods.

It is highly unlikely that the Williamsburg market house served any other purpose. It is significant to note that in 1757 the building committee of the Common Hall were instructed to let the contract for the market house to a carpenter which implies that the structure was to be built of wood. Since there is little indication that the borough court or Common Hall used the market house for its meetings, it seems likely that there was no room above the ground floor market and that the building was in fact a one-story structure used solely for the vending of goods.

The reconstruction of the market house on the market square would benefit many aspects of the interpretation of the economy and society of eighteenth-century Williamsburg. Whether through a static exhibit or through the performance of character interpreters, the lively routine of market day would present an 29 unparalleled opportunity to discuss many aspects of colonial life, ranging from the processing of food to the role of local government through its literal intervention in the market place. Unlike so many places in the Historic Area, it would be possible as well as sensible to have actors interpret different members of society in a place where they could interact in a variety of situations—as buyers and sellers, country people and townsfolk, slaves and masters, petty capitalists and market regulators. Whereas many crafts are interpreted in isolated or unusual places (the basket weaving exhibition at the George Wythe House for example), the market house would be a natural and correct place to have these presented before the public. It would then be possible for the interpreters to go beyond the business of explaining how such objects were made to more important discussions of how they were marketed and used. Centering around the market house too, could be all those civic activities such as the demonstration of the fire engine which are now performed out of context or in isolation. A reconstructed market house and an imaginative interpretation of the myriad of activities which took place around it on market square would help enliven one of the most important areas of eighteenth-century Williamsburg.

Footnotes

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Archives: Block 12; Market House: W. A. R. Goodwin to Harold Shurtleff, March 4, 1931; Minutes of the Research and Records Department Meetings, July 22, 1931; S. P. Moorehead to P. Middleton, March 18, 1954; and M. E. Campioli to A. E. Kendrew, April 27, 1954.

Research memos and reports on the market square and market house include: Helen Bullock, "Market House," June 22, 1932; Helen Bullock, "Markets in Colonial Williamsburg," February 24, 1933; Research Department, "Market and Fairs," 1950; and S. P. Moorehead to M. E. Campioli, "Buildings on Market Square," April 8, 1954.

Appendix

| Date | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1736 | Norfolk | -MH to be 30 by 15 with 6' "overset" on each side; 7' pitch; 4 good posts each side to support the overset; underpinned with brick 3 brick high from surface of the earth; body of the house to be covered with featheredged plank; roof to be shingled; No beef or other meat to be sold anywhere else once MH is built |

| 1737 | Norfolk | -John Taylor, merchant, paid £26 for building the MH |

| 1751 | Belhaven | -money to be raised by lottery to build a MH and church |

| 1752 | Annapolis | -MH to be 40 by 20; 10' pitch; underpinned with brick 4 courses above ground surface; brick floor; 3 doors on each side & one at each end; each door to be 6' wide & 8' high; posts & rafters to be yellow poplar; roof to be of galloping rafters, with a small turret for a bell in the middle; roof & turret to have cypress shingles; weatherboarding to be painted red; loft above with windows |

| 1754 | Annapolis | -market to be held on Wednesdays & Saturdays, market hours — morning till noon; rules stated about selling out of market hours & places outside the MH; injunctions do not apply to fish & oyster sellers |

| 1757 | Williamsburg | -Common Hall to let the construction of a MH to a carpenter |

| 1757 | Norfolk | -markets held on Wednesdays & Saturdays; permission granted to hold them more frequently if so desired |

| 1766 | Norfolk | -shops near the MH on the main street leading from the wharf |

| 31 | ||

| 1766 | Edenton | -warehouse to be laid open as a MH |

| 1768 | Williamsburg | -meat sold by butchers not fit to eat & exorbitantly priced especially during public times; in Norfolk, markets so well regulated that good meat sells at a price the magistrates think reasonable; bakers also sell bread made from bad flour; they should put in the pillory or at least fined |

| 1769 | Norfolk | -store mentioned near the MH |

| 1770 | Winchester | -lottery to be drawn at the MH |

| 1775 | Norfolk | -mention of a tavern near the MH's |

| 1775 | Fredericksburg | -MH built on public square |

| 1777 | Fredericksburg | -house built entirely devoted to dissipation; built of brick (not elegant) & contains a room for dancing & two for retirement & cards |

| 1779 | Williamsburg | -a very convenient store & part of lot where Bartlett Williams lives, opposite the house where Mr Maupin, & near the market in this city, for sale—lately the property of Graham Frank |

| 1782 | Fredericksburg | -MH to be enclosed by post & rail |

| 1782 | Fredericksburg | -country people who come to this market suffer for want of stalls; two new stalls to be erected by the clerk of the market; to be paid by private proprietors of stalls |

| 1782 | Fredericksburg | -gentry to subscribe money for the repair of the town house since it rendered accommodation not only to polite and numerous assemblies, by which youth were greatly benefitted, but also to all sorts of ancient & modern societies of fellowship; building ruinous because of war |

| 1782 | Fredericksburg | -masonic lodge to have use of one of the upper rooms for holding meetings |

| 1785 | Fredericksburg | -MH cleaned; 32 hooks for a new stall; 3 chopping blocks; 3 new stalls completed |

| 1785 | Fredericksburg | -town bell to be hung in front of MH |

| 1787 | Norfolk | -stalls to be let out; shed to be built at west end of MH for purpose of hanging the 32 scales; loft floor to be laid to store provisions brought to market for sale |

| 32 | ||

| 1788 | Fredericksburg | -sand put down in the (fire) engine house & the before the MH; ballroom of MH rented out several times for assemblies |

| 1788 | Fredericksburg | -inhabitants to meet at MH to elect by ballot mayor, recorder, aldermen, & common councilmen |

| 1788 | Fredericksburg | -house to be built over the hay scales |

| 1790 | Norfolk | -MH to be lengthened by 16' from the westernmost end of the same width; also MH to be posted all around 10' from the building with a rail & benches & to be paved within the post |

| 1791 | Norfolk | -four new stalls to be erected on the south side of the MH |

| 1792 | Augusta, Ga. | -butchers to take notice of new regulations governing the new MH |

| 1793 | Fredericksburg | -well and pump to be sunk on MH lot; pair of scales capable of weighing 30 ll to be set up |

| 1796 | Fredericksburg | -part of MH lot to be leased |

| 1796 | Fredericksburg | -question whether present walls capable of carrying a new roof |

| 1796 | Norfolk | -no person with small pox to appear at the MH |

| 1796 | Portsmouth | -Edward Newman to have use of the MH for following year; repairs to be made include glazing all windows, running up a staircase inside the MH, mending the plaster walls; trustees reserve right to use MH on public occasions, Newman to run a partition across MH |

| 1797 | Charleston | -MH to be 150 by 20; the foundation to be sufficiently compact to admit a cistern under the whole; raised 16" above street level; roof to be supported by arched pillars 10 feet high; covered with glazed pan tiles; eaves to project 7' over the pillars on every side; a cupola sufficient to hang a bell, to be in the center; inside to be lathed & plastered, & floor made sufficient for the purpose intended |

| 33 | ||

| 1798 | Portsmouth | -bell to be purchased for the MH |

| 1798 | Portsmouth | -Baptist society has leave to use the MH provided they put a new sill under the door, glaze the windows, and mend the plaster |

| 1798 | Portsmouth | -stalls to be let out for the year for no more than 20 shillings |

| 1799 | Woodstock | -clerk of the market appointed |

| 1799 | Portsmouth | -Baptist society to have leave to use the MH for worship for next year |

| 1799 | Portsmouth | -Jacob Harnage to be appointed clerk of the market with all the perquisites--4/2 for each cord of wood & 6d for each Beef brought to the market |

| 1801 | Portsmouth | -meeting of the inhabitants of Norfolk County to be held at Portsmouth town hall |

| 1801 | Fredericksburg | -bell to be affixed to the MH |

| 1801 | Fredericksburg | -stalls to be rented out to highest bidder |

| 1803 | Portsmouth | -shutter of MH to be repaired |

| 1803 | Portsmouth | -MH to be rented out as a school |

| 1803 | Fredericksburg | -floor & yard next to the street to be paved with brick & railing repaired |

| 1804 | Norfolk | -new MH to be built |

| 1804 | Norfolk | -MH to be built at the north side of Water Street & run up in the middle of Market Street towards main |

| 1804 | Portsmouth | -lock for MH door |

| 1804 | Portsmouth | -MH repaired & painted |

| 1804 | Portsmouth | -clerk of the market to cause the negroes who are in the habit of using the MH as hucksters to quit, nor are they allowed to sit in the environs of the same |

| 1805 | Norfolk | -sale of old MH not advisable at this time; the present brick pavement and outside parts are useful to the public |

| 1805 | Norfolk | -old MH can now be sold except the pavement and outside posts |

| 34 | ||

| 1806 | Portsmouth | -fine for forestalling; copies of the law regulating the market to be printed |

| 1806 | Raleigh | -roof & belfry of MH to be painted, also mounting a ball and vane |

| 1806 | Portsmouth | -market pump repaired |

| 1806 | Portsmouth | -five stalls rented for $10 a year |

| 1807 | Charleston | -fish market to be built of same dimensions as the one at the end of Queen Street; foundation to be 4 bricks thick to the height of 9'; roof to be supported on pillars 22 ½" by 4' to be carried up ten feet above the floor |

| 1807 | Fredericksburg | -engine together with axes & fire hooks to be kept in the usual room in the MH |

| 1808 | Edenton | -new MH to be built |

| c. 1809 | Norfolk | -new MH made fit for winter; propted on pillars; butchers' shambles stuck in between; railing around MH; vegetables sold there; ascend steps; market over by 8:00AM; after market the place looks wrecked |

| 1811 | Portsmouth | -market regulations: all provision brought to market except fish & oyster to be sold at the MH; anyone selling or buying outside the limits of the MH during market hours will be fined; every beef brought to market the owner shall pay the clerk 9d; bad meat or poultry sold or meat left long keeping shall be publickly burned; no forestalling of provisions, fruit, or firewood; meal shall be weighed; seller shall pay clerk 6d for each cord of firewood; limits of the market area delineated; clerk shall attend market from sunrise to 11 oclock, after that time the market hours shall cease; these rules to be set up in the MH |

| 1811 | Portsmouth | -clerk to regulate carts coming to market; MH to be swept daily & the environs at least once a week |

| 1812 | Fredericksburg | -house built over hay scales; MH painted & whitewashed |

| 35 | ||

| 1813 | Fredericksburg | -MH to be illuminated to celebrate the glorious success against the enemy |

| 1814 | Norfolk | - MH to be rebuilt on site on one lately destroyed |

| 1814 | Fredericksburg | -estimates for a new MH $6250 (the present MH) |

| 1814 | Fredericksburg | -new MH to be built |

| 1814 | Leesburg | -remnant of the old MH now standing on the public lot to be removed |

| 1816 | Portsmouth | -benches to be erected on each side of the MH |

| 1816 | Richmond | -MH to be erected on Shockoe Hill |

| 1817 | Portsmouth | -MH to be laid out into five butcher stalls; to be rented for $20 per year with no more than two stalls rented by one butcher |

| 1817 | Portsmouth | -benches to be erected around the MH and sheds thereof to be extended |

| 1817 | Portsmouth | -MH & sheds to be paved with stones; a strong post to be planted between each standard of the sheds |

| 1818 | Portsmouth | -dirt to be infilled around the MH and under the shed, and a good chinquipin post planted between each standard of the shed |

| 1820 | Portsmouth | -stalls to be rented for no less than $20 per year |

| 1821 | Portsmouth | -MH & sheds to be rebuilt where they originally stood except for the chimneys |

| 1821 | Fredericksburg | -room in the MH to be fitted out for the use of the mayor |

| 1821 | Portsmouth | -brick rubbish around the MH to be removed |

| 1821 | Portsmouth | -a plain table & 12 windsor chairs to be procured for the trustees |

| 1822 | Fredericksburg | -MH to be lathed & plastered |

| 1823 | Fredericksburg | -MH to be paved with brick and ceiled with lath & plaster |

| 1824 | Fredericksburg | -committee appointed to receive Lafayette |

| 36 | ||

| 1824 | Fredericksburg | -MH to be painted; door moved to the front of the steps |

| 1824 | Fredericksburg | -reception held for Lafayette at MH |

| 1825 | Portsmouth | -MH scoured |

| 1825 | Portsmouth | -upper part of MH whitewashed |

| 1825 | Portsmouth | -MH pump repaired |

| 1826 | Fredericksburg | -mayor's office altered |

| 1826 | Fredericksburg | -stall reserved for the country people |

| 1826 | Lynchburg | -public scale house to be erected |

| 1827 | Fredericksburg | -fish carts a nuisance to the public |

| 1827 | Fredericksburg | -the apartment at the end of the MH enclosed for a cage to be rented but not to store fish or offensive articles therein |

| 1827 | Fredericksburg | -hay scales erected |

| 1827 | Lynchburg | -hay scales and a suitable house over the same to be erected |

| 1828 | Lynchburg | -man paid for curbing, excavating, and paving at the hay scale |

| 1828 | Portsmouth | -ordinance passed prohibiting the use of steelyards for weighing meats that are sold at the stalls in the MH |

| 1830 | Portsmouth | -MH to be extended 60' to the east of the same as the present MH & to be one story high |

| 1830 | Portsmouth | -MH built by Thomas Scott received; new part of MH to be filled up and paved; outside plank to be painted; footways to be paved; necessary hooks & braces to be erected; old wall of old house to be taken down |

| 1830 | Portsmouth | -4 benches made for the wing of the MH |

| 1833 | Fredericksburg | -5 stalls & the cage rented |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -new MH patterned after one in Norfolk to be 120 by 22 |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -length of new MH to be increased 20' and pitch increased by one foot; brick work to be worth $541 and woodwork $630 |

| 37 | ||

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -MH to be built after the plan of the Norfolk one; 124' long, 12' height, with 6' eaves; George Bain to do the brickwork and find the materials for $500; Miles Minter to do all woodwork & find materials for $550 |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -MH to be 124 by 22; 13' high; twelve openings on each side 6' wide, and one in each end 14' wide; the walls two bricks thick with all laid bricks in a workmanlike manner; basement story to be dispensed with, $2500 set aside to build the MH |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -rafters to project 6' beyond without posts to support them the pillars |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -MH to be paved and plastered |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -MH to have two coats of plaster; roof painted with one coat of fireproof paint, with the end & cornice three coats of white lead paint; MH to be graded & paved with hard Baltimore or Alexandria bricks (curb stone for the same 4" thick & 16" deep) for $526 or less |

| 1835 | Portsmouth | -stalls from old MH to be put in the new |

| 1836 | Portsmouth | -stalls, benches, & scales put in new MH |

| 1839 | Fredericksburg | -question whether or not iron railing with gates were appropriate across the several entries into the market space |

| 1840 | Fredericksburg | -young men's society given leave to rent one wing of the MH now used by the infant school |

| 1841 | Fredericksburg | -lodge not allowed a room in the MH |

| 1845 | Fredericksburg | -bookcases put in mayor's office |

| 1845 | Fredericksburg | -debate whether to fill up a hole in front of the MH or make it a place for the pump to be used for cleaning the MH |

| 1850 | Fredericksburg | -disorderly behavior evident at exhibitions, shows, concerts, etc. in the MH |