Wren Building at the College of William and Mary Restored: Summary Architectural Report of Interior Restoration 1967-1968 Block 16 Building 3The Wren Building at the College of William & Mary (Block 16, Building 3) Restored Summary Architectural Report of Interior Restoration: 1967-1968

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0194

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE WREN BUILDING at THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM & MARY

(Block 16, Building 3)

RESTORED

SUMMARY ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

of

INTERIOR RESTORATION: 1967-1968

Architects' Office

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

June, 1968 (Revisions: July, 1979)

THE WREN BUILDING

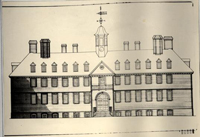

Façade

Drawing by Singleton P. Moorehead

Drawing by Singleton P. Moorehead

Architects' Office

The colonial Williamsburg Foundation

[1958]

See: Marcus Whiffen's The Public Buildings of Williamsburg (Williamsburg Virginia: Colonial Williamsburg, 1958), Figure 38, page 102.

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

By means of steel beams and concrete footings, the interior framework is supported independently of the exterior walls.

PB note

re: "curtain wall" construction

Daguerreans

[HANDWRITTEN NOTE]

Previous Public Bldg:

Church Jamestown

(3) State House, Jamestown

Bruton Church, Wmsbg.

By time 2nd Bldg. finished:

Spotswood's energetic building accomplishments -

Capitol (1705)

Palace - ca. 1716.

Gaol

Magazine

Bruton Church.

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

RG Checked in sketches

File

(B1. 16 #3.)

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Ck - fireplace in plan

ELP.

Sketch SK-

p. 50-A.

(Summary Report)

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

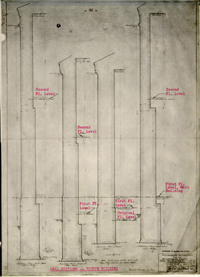

Main Building of College Wm. & Mary

#120

dated 8/1/29

by John A. Barrows

checked WMM OMB

rev. March 10, '30 OMB

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Main Building of College of W. & M.

Dwg. #117

8/1/29 John A. Barrows

3/4"

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Main Bldg. of College of W. & M.

#118

8/1/29

John A. Barrows

rev. 9/30/30 RAW

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Wren Bldg. alt.-

June 16, 1967

1/8" = 1'-0"

JFW

A 2

Rev. 8-11-67

9-26-67

ELP

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Wren Bldg, Alterations

June 16, 1967

1/8" = 1'-0"

ELP

A 1

Basement [cellar] Plan

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Wren Bldg. alt.

June 16, 1967

1/8"=1'-0"

ELP

A 3

6-21-67 ELP

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Wren Bldg. alt.

June 16, 1967

1/8"-1'-0"

1/4" = 1'-0"

ELP

A 4

Rev.

6-21-67

7-12-67

9-26-67 ELP

53-DB-4846 An old photograph showing the ravaged walls after the fire of 1859 corroborating the archaeological evidence.

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Photo of ptg. given CW by Miss Ellen Bagby of Richmond (for many years active in A.P.V.A.)

Whereabouts of ptg. unknown, artist unknown.

8-18-71 Mrs. Goodwin says that Miss Bagby gave C.W. a photograph of her original ptg. - Where is that photo?

WREN-

RAVAGED WALLS AFTER FIRE [illegible]

(c.1953) Rec'd.

[HANDWRITTEN NOTE]

p.33.

Several other locations were considered and Townsend Lands or the Lands of Col. Townsend on the South Side of York River - was the site specified in the charter.

[HANDWRITTEN NOTE]

fn. only about 30 acres of the orig. tract remain.

See: pp. 33-34- Hist Notes

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

[illegible]

GRADE RAISE OF 3 FT. (P. 18)?

How, since whole plot is level?

From Archaeo. Report + docu records and evidence of drain tunnel

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

I thought that Michel was Swiss. Was he French?

(p. 17)

yes - Swiss

[illegible]

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

Where did you get the Jazzbo about Curtain Walls (p. 13)? It isn't right I don't think.

Cleverdon Report

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

[illegible] The fireplace is [sketch], not [sketch] in plan, isn't it?

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

(p. 74) The common room is virtually the same size (and would have originally been a tad larger) as the moral philosophy room below.

ck. dimensions

Ones I have say Common Rm. slightly smaller

PHOTOCOPY OF HANDWRITTEN NOTE - [no digital image available]

(p. 14) I read Michel's drwg as having the door above the bsmt instead of into it.

CK

[HANDWRITTEN NOTE]

Put: Room Numbers

Dimensions

Ceiling heights

Change page #s.

Xerox pages back/front

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Title Page | |

| Table of Contents | |

| List of Illustrations | |

| Restoration Chronology (C.W.F.: 1928-1968) | 1. |

| Preface | i. |

| Historical Chronology (W.& M.: 1963-1979) | 3. |

| Bibliography | 6. |

| [Index] | |

| PART I: Historical and Architectural Research | |

| Historical Summary | 7. |

| Restoration Summary | 9. |

| Condition | 12. |

| The First Wren Building (1695-1705) | 14. |

| The Second Wren Building (1710-1859) | 22. |

| Pictorial Records of the Second Wren Building | 29. |

| Design | 30. |

| The College Environs | 31. |

| PART II: The Interior of The Wren Building | |

| Plan | 34. |

| General Notes | 35. |

| Ceiling Heights | 36-37. |

| First Floor | 37. |

| Lobby | 37. |

| Main Stair Passage | 39. |

| Piazza | 41. |

| South Stair Passage | 43. |

| North stair Passage | 45. |

| Grammar school Room | 45. |

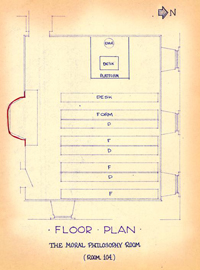

| Moral Philosophy Room | 50. |

| The Great Hall | 52. |

| The Chapel | 59. |

| Second Floor | 68. |

| The Long Corridor | 68. |

| Lobby | 69. |

| The Convocation ("Blue") Room | 69. |

| Common Room | 73. |

| ADDENDA | |

| Appendix I: Memorandum of Several Faults..." | 77. |

| Appendix II: The Wren Controversy | 78. |

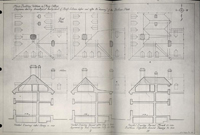

| Appendix III: Floor Plans | 87. |

| FOOTNOTES | 88. |

| [INDEX] | 92. |

| PAGE | |

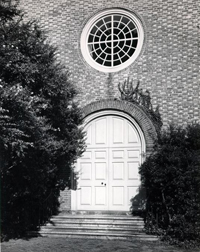

| The Wren Building: East Elevation. Restored. (Drawing by Singleton P. Moorehead, C.W.F., 1958.) | Frontispiece |

| The Wren Building: East Elevation. Restored. (C.W.F. Negative #K62-JC-446.) | 6. |

| The Wren Building: West Elevation. Restored.(C.W.F. Negative #51-W-341.) | 7. |

| Dormitory Room Depicted in The Second College Building.(Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, August 17, 1866.) | 10. |

| The Fourth College Building: Southeast View.(Photograph, unknown photographer, 1870s.) | 12. |

| The First College Building: Outline of Original Plan. (Survey Map by Theodorick Bland, 1699.) | 14. |

| The First College Building: East Elevation. (Watercolor sketch, Franz Ludwig Michel, c.1702.) (C.W.F. Negative #L-185.) | 17. |

| The Second College Building: Southeast View. (Portrait: James Blair; attr. Charles Bridges, c.1735.) (C.W.F. Negatives #N-4234; #L-179; #51-T-1629.) | 21. |

| The Second College Building: East Elevation - College Yard. (Bodleian Copperplate, engr. unknown, c.1740.) (C.W.F. Negative #N-4172.) | 22. |

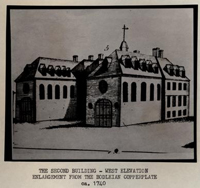

| The Second College Building: Southwest View. (Bodleian Copperplate, engr. unknown, c.1740.) (C.W.F. Negative #N-4173.) | 25. |

| The Second College Building: East Elevation. (Daguerreotype, unknown photographer, c.1856.) (C.W.F. Negative #N-1960.) | 29. |

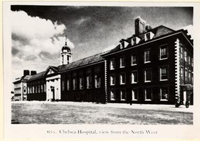

| Chelsea Hospital, London, England. (Design by Sir Christopher Wren, 1682-1691.) (Photostat: Engraving by S Nicholls, c.1700.) | 30. |

| Arlington House in [London], England. (Photostat:: Engraving by S. Whitehead, n.d.) | 31. |

| College Yard: The Second College Building; The Brafferton; The President's House. View: East Front. (Bodleian Copperplate, engr. unknown, c.1740.) (C.W.F. Negative #N-4986.) | 32. |

| Layout of The College of William and Mary. (Frenchman's Map, unknown cartographer, c.1782.) (C.W.F. Negative #N-3436.) | 34. |

| The Second College Building: Floor Pan & Addition. (Drawing by Thomas Jefferson, c.1772.) (C.W.F. Negative #L-189.) | 35. |

| -2- | |

| The Wren Building: Piazza (Restored). Northwest View. (C.W.F. Negative #53-2055.) | 41. |

| The Second College Building: West Elevation. (C.W.F. Negative #L-184.) | 42. |

| The Grammar School Room: (Restored). Northwest View. (C.W.F. Negative #68-SMT-1573.) | 45. |

| The Grammar school Room: (Restored). Southwest View. (C.W. F. Negative #68-SMT-1573.) | 45. |

| Eton College, Buckinghamshire, England. Headmaster's Desk, Upper School Room. (Design attr. Sir Christopher Wren, 1694.) | 46. |

| Eton College, Buckinghamshire, England. Assistant's Desk, Upper School Room (Design attr. Sir Christopher Wren, 1694.) | 46. |

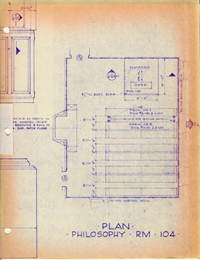

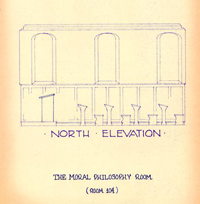

| The Moral Philosophy Room: (Restored). Floor Plan. (Drawing by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1967.) | 50. |

| The Moral Philosophy Room: (Restored). North Elevation. (Sketch by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1967.) | 51. |

| The Great Hall, (Restored). View to West End of Room. (C.W.F. Negative #68-SMT-1574.) | 52. |

| The Great Hall, Chelsea Hospital, London England (C.W.F. Negative #67-CK-393.) | 53. |

| The Great Hall: (Restored). East Elevation. (Drawing by John A. Barrows, C.W.F., 1929-1930.) | 54. |

| The Great Hall: Exterior (Restored). West Elevation. (C.W.F. Negative #46-W-658.) | 55. |

| The Chapel: (Restored). East View of Altar. (C.W.F. Negative #52-W-150.) | 59. |

| The Chapel: (Restored). View of West End of Room. (C.W.F. Negative #66-SMT-1921.) | 59. |

| Christ Church, Newgate Street, London, England. (Design by Sir Christopher Wren, 1677-1687.) | 63. |

| The Chapel, Chelsea Hospital, London, England. | |

| The Chapel, Trinity College, Oxford University. (Design reviewed by Sir Christopher Wren, 1692.) | 63. |

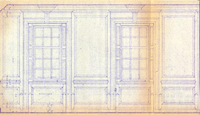

| The Convocation ("Blue") Room: North Elevation. (Drawing by John A. Barrows, C.W.F., 1929.) | 69. |

| The Convocation ("Blue") Room: East Elevation (Drawing by John A. Barrows, C.W.F., 1929-1930.) | 69. |

| The Common Room: (Restored). Elevations. All Walls. (Drawing by John A. Barrows [?], C.W.F., 1929) | 73. |

| The Common Room: (Restored). Design of Floorcloth. (Drawing by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1968.) | 76. |

| -3- | |

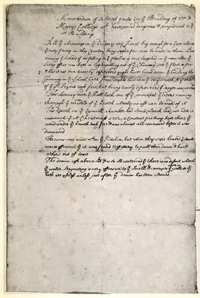

| Appendix I | PAGE |

| "Memorandum of several faults in the Building of William and Mary Colledge..." Francis Nicholson Papers, Manuscripts Collection, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. c.1704-1705. (C.W.F. Negative #57-CL-224.) | 77. |

| Appendix II | |

| Chelsea Hospital, London, England: Northwest View. (Design by Sir Christopher Wren, 1682-1691.) | 78. |

| Appendix III | |

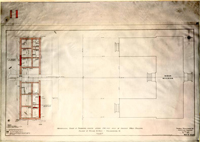

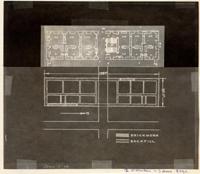

| The Wren Building: Basement [Cellar] Plan. Alterations. (Drawing by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1967.) | 86. |

| The Wren Building: First Floor Plan. Alterations. (Drawing by James F. Waite, C.W.F., 1967.) | |

| The Wren Building: Second Floor Plan. Alterations. (Drawing by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1967.) | |

| The Wren Building: Third Floor Plan. Alterations. (Drawing by E. Leroy Phillips, C.W.F., 1967.) | |

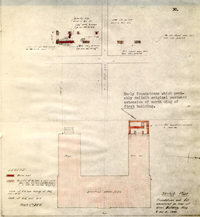

| The Wren Building: Quadrangle Foundations Excavated. (Drawing by James M. Knight, C.W.F., 1950.) | |

| The Wren Building: Quadrangle Foundations Discovered. (Drawing by James M. Knight, C.W.F., 1940.) | |

| The Wren Building: Comparison of Excavated Quadrangle Foundations (1950) with Jefferson's Plan for An Addition to the College (c.1772). (Sketches, Architects' Office, C.W.F., 1950.) | |

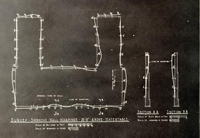

| The Wren Building: Wall Sections of Fourth Building. (Drawing by J. Everette Fauber, C.W.F., 1930.) | |

| The Wren Building: Structural Survey of Wall Warpings. (Drawing by Herbert S. Cleverdon, C.V.&P., 1930.) | |

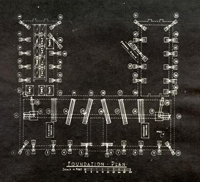

| The Wren Building: Foundation Plan - Footings. (Drawing by Herbert S. Cleverdon, C.V.&P., 1930.) | |

| The Wren Building: Roof Sections - Before and after Discovery of Bodleian Plate in 1929. (Drawing by Andrew H. Hepburn, P.S.&H., 1947.) | |

| The Second College Building: Ruins after 1859 Fire. (Painting, 1859, Ownership and Artist Unknown.) (C.W.F. Negative #53-DB-4846.) | Finis |

| Footnotes | |

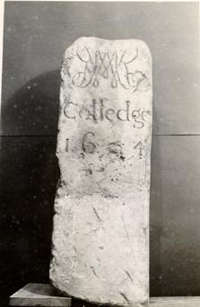

| Meare [Boundary] Stone: The College of William and Mary. Inscribed: 1694. Original at Swem Library. (C.W.F. Negative #63-CK-677.) | 87. |

SUMMARY ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

The Wren Building was restored during 1928-1931 by The Williamsburg Holding Corporation (corporate precursor of Colonial Williamsburg) under the direction of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Architects. Cleverdon, Varney, and Pike, Engineers, was the structural consulting firm. The contractor was Todd and Brown, Inc. That project involved complete exterior restoration and partial interior restoration.

| Restoration started: | June, 1928 |

| Restoration was completed: | June, 1931 |

Adaptation of the interior in 1928 assured that the Wren Building would continue to function in its original educational role with modernly equipped classrooms and offices. Subsequently, during 1967-1968, six rooms in the Wren Building were restored to authentic eighteenth-century appearance by the Architects' Office of Colonial Williamsburg for exhibition purposes.

| Restoration started: | June, 1967 |

| Restoration was completed: | June, 1968 |

Catherine Savedge

Architectural Research Department

Colonial Williamsburg

June, 1968

PREFACE

The following summary report records architectural changes made at the Wren Building during a partial restoration conducted in 1967-1968. This recent project entailed only interior restoration, and was confined to six rooms of prime historical significance. Its purpose was to revise certain areas of the Wren Building, according to documented scholastic usage, for display among buildings in Colonial Williamsburg's exhibitions program. As first treated in 1928, these rooms were not fully restored, but, rather, fitted as modern classrooms and meeting rooms (one of the latter in accordance with long-standing tradition identifying it as domain of the faculty and Board of Visitors), so that the structure would continue to fulfill its active, educational role.

The current architectural work, along with arrangements for regularly scheduled conducted tours for to the public, were implemented through special agreement with The College of William and Mary. Founded in 1693, under authority of the Church of England, it The College has operated since 1906 as a state institution of higher education. Ownership of all structures at the College hence resides with The Commonwealth of Virginia.

Drawings for this project were executed by E. Leroy Phillips of the Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg, in consultation with Paul Buchanan, Director of Architectural Research. Mrs. Mary R. M. Goodwin's Research Report (1967), written in Colonial Williamsburg's (ii) Research Department, provided documentary and pictorial reference to substantiate these renovations. Limitations imposed by scanty primary source material detailing the Wren Building's original interior appearance meant that much specific precedent for academic features had to be derived from traditional arrangements surviving among historic preparatory schools, colleges, and universities in England. Virginia's colonial stylistic mannerisms, however, were followed throughout in interpreting British design prototypes.

This report concerns primarily the six rooms thus restored to an authenticity reflecting the Wren Building's early (c.1716-1779), vibrant period of scholarship and architectural development. Reorganization of the College curriculum under Governor Thomas Jefferson's innovations in 1779 afterwards reassigned the usages of particular rooms. Outlined here, therefore, are architectural descriptions and supportive evidence for alterations accomplished in 1968. Those rooms undergoing major change included:

| 1. | The Grammar School Room | (24' x 32'3") |

| 2. | The Moral Philosophy Room | (20' x 24') |

| 3. | The Great Hall | (25'6" x 59') |

| 4. | The Chapel | (25'6" x 59') |

| 5. | The Convocation ("Blue") Room | (24'3" x 32'4") |

| 6. | The Common Room | (19'10" x 24'4") |

The present report is an interim summary, intended to provide factual update supplementary to Howard Dearstyne's definitive (1951), two-volume Architectural Report on The Wren Building. More comprehensive studies must be consulted for complete analysis of the Wren Building, the history of the College, and the background of all structures and features related to the eighteenth-century College Yard, including the two other, colonial, brick structures situated there -- The Brafferton and The President's House which unify the original scheme. A list of related documents and sources can be found in the selected Bibliography which accompanies this report.

Catherine Savedge

Architectural Research Department

Colonial Williamsburg

June, 1968

[Revised: (CSS) July 10, 1979]

The Summary Architectural report is a resume of information on the subject building, condensed form data filed in the Architects' Office. It is intended for the use of authorized personnel within Colonial Williamsburg and visitors having a serious interest in colonial American architecture. It is not for public distribution.

THE WREN BUILDING -- HISTORICAL CHRONOLOGY

| 1693 | - (February 8) Royal Charter founded The College of William and Mary. |

| - Queen's College, Oxford University, England built by Sir Christopher Wren. | |

| - School at Appleby, Leicestershire, England designed by Sir Christopher Wren. | |

| - All Hallows Church, Lombard Street, London, England built, at Sir Christopher Wren's design. | |

| 1695 | (August 8) Foundation of First Wren Building Laid. |

| 1699 | Theodorick Bland Survey |

| 1700 | First Wren Building Completed. |

| 1702 | Franz Ludwig Michel's Drawing of First Building. |

| 1705 | - (October 29) First Wren Building Burned. |

| - Robert Beverley published The History and Present State of Virginia (London: 1705), 1st edition. | |

| 1709 | Second Wren Building Begun. |

| c.1716-1718 | Second Wren Building Completed according to new design by Governor Alexander Spotswood. |

| 1723 | Sir Christopher Wren's death. |

| 1723-1724 | The Brafferton Constructed |

| 1724 | Hugh Jones published The Present State of Virginia (London). |

| 1728-1732 | Chapel (South Wing) Built: Second Wren Building Complete. |

| 1732-1733 | The President's House Constructed. |

| c.1733-1746 | The Bodleian Copperplate Engraved [Oxford University, England] |

| 1735-1740 | Portrait of James Blair (attr. to Charles Bridges). Detail: Façade of Second Wren Building & Phoenix Rising from Flames. |

| c.1771-1772 | Thomas Jefferson's Floor Plan: Design for Enlargement of Original Quadrangle Scheme (into rectangle) at Request of Governor John Murray, Lord Dunmore. |

| 1774 | Quadrangle Addition Construction Begun. |

| (4) | |

| 1776 | American Revolution: College of William & Mary lost British ecclesiastic support, patronage, and crown revenues. |

| 1779 | Curriculum established under (1693) Royal Charter Revised by Virginia General Assembly under scholastic innovations of Governor Thomas Jefferson. |

| 1780 | Quadrangle Addition Abandoned because of Revolutionary War. |

| 1781 | General Cornwallis occupied President's House as Military Headquarters before final Revolutionary battle. |

| Wren Building and President's House occupied as Hospitals following Cornwallis' Surrender at Yorktown. | |

| 1781 | (November 23) President's House Burned while Occupied by wounded French Officers. |

| c.1782 | Frenchman's Map depicts College Layout. |

| 1786 | President's House Rebuilding Completed with Funds Appropriated by Government of France. |

| Late 18th c | [Humphrey Harwood Accounts for Repairs to College Structures.] |

| 1801 | Statue of Lord Botetourt Bought & Erected in College Yard. |

| c.1820 | Painting of Second Wren Building by Unknown Artist. |

| c.1840 | Watercolor of Wren Building by Thomas Charles Millington. |

| Lithograph of Second Wren Building by C. L. Ludwig. | |

| 1856 | Extensive Renovations to Second Wren Building. |

| c.1856 | Daguerreotype of Wren Building by Unknown Photographer. |

| "Little Girl's Drawing" of Front and Rear of Wren Building by Mary F. Southall. | |

| 1859 | (February 8) Second Wren Building Burned. (Eighteenth-Century Stone Tablets in Chapel Calcined.) |

| Unidentified Sketch of Ruins. (Original & Source Unknown.) | |

| Third Wren Building Constructed. Italianate Design by Henry Exall and Eben Faxon, Architects. | |

| 1862 | (September 9) Third Wren Building Burned by Union Soldiers. Burial Vaults beneath Chapel Plundered during Civil War, and Botetourt Statue temporarily moved to Eastern State Hospital. |

| (5) | |

| 1867-1869 | Fourth Wren Building Constructed. Alfred L. Rives, of Richmond, Architect. |

| 1888-1919 | Two Original Boundary (Meare) Stones placed flanking Wren Building Steps by President Lyon G. Tyler. |

| 1893 | United States Government partially Indemnified College for Losses Sustained during Revolutionary and Civil Wars. |

| 1906 | Ownership of College transferred to The Commonwealth of Virginia. (Corporation known as "President and Masters or Professors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia" became "The College of William and Mary in Virginia".) |

| 1928-1931 | Wren Building Restoration (c.1716-1859 period). Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Architects, of Boston, Massachusetts. John Davison Rockefeller, Jr., patron. |

| (Restoration of the Wren Building was accomplished through joint consultations of the architects, Perry, Shaw & Hepburn; their Advisory Committee of Architects; President J. Alvin C. Chandler and the State Art Commission representing The Commonwealth of Virginia. Engineers were Cleverdon, Varney, and Pike of Boston, Massachusetts. Contractors were Todd & Brown, Incorporated of New York City. Chief Archaeologist was Prentice Duell.) | |

| 1950 | Foundations of (1774-1780) Quadrangle Addition Discovered and Excavated. James M. Knight, Archaeologist, Colonial Williamsburg. |

| 1966 | Botetourt Statue (Norborne Berkeley, Baron de Botetourt, [1718-1770], Governor of Virginia, 1768-1770) by Richard Hayward, sculptor, of London. Set up in Capitol portico, 1773; moved to College Yard, 1801; temporarily moved to Eastern state Hospital, 1862-c.1869; transferred into the Swem Library, 1966. |

| 1967-1968 | Partial Interior Restoration of Wren Building (Six Rooms). Ernest M. Frank, Resident Architect, Colonial Williamsburg. |

| 1970 | Burial Vaults beneath Chapel Vandalized. Inspection led to positive identification (for first time in College research) of Lord Botetourt's tomb. |

| 1979 | Burial Vaults beneath Chapel again Disturbed. |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

THE WREN BUILDING OF THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY

Illustration: Draft Title Page for Howard Dearstyne's (1950) Architectural Report.

This building was restored by the Williamsburg Holding Corporation under the direction of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, Architects

This volume contains the following:

- A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FOUR FORMS OF THE BUILDING

(Archaeological Report, 1932) by Prentice Duell - ARCHITECTURAL REPORT ON THE RESTORATION OF THE WREN BUILDING

by Thomas T. Waterman - NOTES ON THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ROOF OF THE WREN BUILDING

by Andrew H. Hepburn 1947 - STRUCTURAL FEATURES IN THE RESTORATION OF THE WREN BUILDING

by Herbert S. Cleverdon - EVENTS IN THE ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY OF THE WREN BUILDING

by A. L. Kocher and H. Dearstyne

The material in this volume was assembled and supplementary notes and illustrations were added by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne - September 29, 19[deleted]

[PHOTOCOPY OF CARD]

Morpurgo, J. E. Their Majesties' Royall Colledge: William and Mary in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries. Williamsburg, Virginia: The Endowment Association of The College of William and Mary of Virginia, Incorporated., 1976.[Jack E.] Morpurgo.

Washington, D.C.: Hennage Creative Printers

378.75

M871

c.3 Research Library

Available: Alumni Office (W&M) $25.00 (7/23/79)

- Bullock, Orin M. Wren Building: Architectural Report. Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg: Unfinished draft report, 1959. Typed: May, 1968.

- Dearstyne, Howard. The Wren Building of the College: Architectural History. Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg: Architectural Report (typescript), 1950. Revised: 1951. 2 volumes.

- [This report includes three important articles as follows.]

- Cleverdon, Herbert S., "Structural Features in the Restoration", II, 114-138.

- Hepburn, Andrew H., "Notes on the Reconstruction of the Roof", II, 109-112.

- Addendum: "Supplementary Facts about the Restoration of the Building", II, 138-a-138-s.

- Duell, Prentice. The Wren Building: A Brief History of the Four Forms of the Building. Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg: Archaeological Report (typescript), 1932.

- Duell, Prentice. The Wren Building, College of William and Mary: Literary References. Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg: Research Report (typescript), n.d. [c. 1930].

- Goodwin, Mary R. M. Historical Notes: The College of William and Mary. Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg: Research Report (typescript), 1954. 5 volumes.

- Goodwin, Mary R. M. Notes on the "Wren" Building of the College of William and Mary: A Brief Sketch of the Main Building of the College and of the Rooms to be Restored to their Eighteenth-Century Appearance. Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg: Research Report, (multilith), 1967.

- Goodwin, Mary R. M. The President's House and the Presidents of the College of William and Mary. Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg: Research Report (typescript), 1975. -2-

- Kocher, A. Lawrence and Dearstyne, Howard, "Discovery of Foundations for Jefferson's Addition to the Wren Building", Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, X. no. 3 (October, 1951 [?]), 28-31.

- Moorehead Singleton P. Wren Building Furnishings Report. Architects' Office, Colonial Williamsburg: Special Study, compiled c. December, 1962. Typed: October, 1964.

- Nash, Susan H. Notebooks, Papers, and Photographs Related to the Restoration of the Wren Building. Nash Papers (1927-1934), Architects' Office, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1971.

- Savedge, Catherine. The President's House: 1776. Architects' Office, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Report for Antiques Forum Speech by Roy E. Graham, Resident Architect (typescript), 1976.

- Savedge, Catherine. The Wren Building: Exterior. Architectural Research Department, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Summary Architectural Report (typescript), 1968.

- Savedge, Catherine. The Wren Building: Interior Restoration: 1967-1968. Architectural Research Department, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Summary Architectural Report (typescript), 1968.

- Savedge, Catherine. The Wren Building: Architectural Summary of Interior Restoration, 1967-1968. Architectural Research Department, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Architectural

ReportSummary (typescript), 1969. - Savedge, Catherine. The Wren Building: The Chapel Burial Vaults and Memorial Tablets. Architectural Research Department, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation: Special Study (Unfinished draft report), 1970.

- Waterman, Thomas T. Architectural Report on the Restoration of The Wren Building. Williamsburg, Virginia: Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Architects, c.1932.

- Whiffin, Marcus. The Public Buildings of Williamsburg. Williamsburg, Virginia: Colonial Williamsburg, 1958. (Second printing: 1968.)

- The Architectural, Structural, and Mechanical Working Drawings; The Specifications; Photograph Albums of Progress and Completion Pictures; The Architectural Research Files (Block 16, Buildings #1, #2, #3). Architectural Research Library, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1927-present.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Sir Christopher Wren Building of the College of William and Mary stands at the western end of Duke of Gloucester Street. Facing due east, it overlooks the three-quarter-mile avenue which, in the eighteenth century, linked the important public edifices of the Virginia Colony. "The College" or "the Main Building of the College", as the Wren Building was known for two centuries, is the oldest academic structure in America and the earliest building extant in Williamsburg. Its brick walls have stood for 273 years. The Wren Building, in fact, pre-dates the founding of Williamsburg. It appears today in its fifth form, having suffered the been devastationed of by three fires before being its restorated ion during 1928-1931. Its present appearance is a restoration of the Second Building (1716-1859).

HISTORY:

The Royal Charter establishing " William and Mary College in Virginia"1 was granted on February 8, 1693. After considering four locations,2 the General Assembly selected Middle Plantation3 as the site for the College, ordering on November 18, 1693 "that the said college be at that place erected and built as neare the church now standing in Middle Plantation old ffields as convenience will permitt."4 A month later the College visitors purchased from Colonel Thomas Ballard 330 acres of land for the College environs. The property was situated west of the seventeenth-century Bruton Parish Church; it extended as far south as Archer's Hope Creek and westward to Ludwell's Mill (Lake Matoaka). Boundary stones, inscribed with the date and the monogram of King William and Queen Mary, were erected in 1694 to mark the College acreage.5 The site for the College buildings was chosen near the eastern extremity of the College lands, about 1,716 feet (104 poles) from the Church.

Page 8The first foundation bricks for the Wren Building were laid on August 8, 1695. Construction progressed slowly, but by 1699 the building was in use; by 1700 it was essentially complete. Accurately, the Wren Building has never been finished, for only three sides of its intended quadrangular plan were ever realized. Two parts of the proposed square, the east block and the north wing, were standing when the President, masters, ushers, and students took occupancy following the Christmas vacation of 1700. The First Building survived for a period no longer than that which elapsed during its construction. Fire gutted the building on October 29, 1705, destroying everything but the substantial brick walls (three-and-a-half feet thick at the base) and some moveable property. Despite controversy, the old walls were used in rebuilding the College. The Second Building, like the first, consisted of the east portion and the north wing. It was completed ca. 1716-1718. The third site of the envisioned quadrangle was erected during 1728-1732, when the south wing (Chapel) was built to correspond to the north wing (Great Hall). The idea of finishing the original design of the College quadrangle persisted for eighty years. Around 1771 or 1772 Thomas Jefferson draughted a floor plan for the, completion of the square. Foundations for the addition were partially laid, but the work was interrupted by the Revolution and never resumed. By the middle of the nineteenth century recurrent repairs and alterations had slightly changed the appearance of the building. Extensive interior renovations were made in 1855-56, but the improvements were short-lived. On the College's 166th Charter Day, February 8, 1859, the building burned a second time. Though the walls were severely warped and cracked Page 9 by the fire, they were again incorporated in the work of reconstruction. The Third Building, speedily erected, was completed within the year. The effort expended in replacement was soon negated by disaster, for the Wren Building was once more consumed by flames on September 9, 1862. Less damage was inflicted on the walls by the third fire than in the two previous conflagrations, but seven years passed before the structure was rebuilt. Maintaining the continuity, the Fourth Building was raised on the original walls. It was completed in 1869 and stood intact until 1928.

RESTORATION:

Between 1928 and 1931 the Wren Building was restored by the Williamsburg Holding Corporation, predecessor of Colonial Williamsburg. The project was undertaken through a reciprocal agreement between the College of William and Mary (the owner) and the restoration corporation. Appropriately, the Wren Building was the first structure in Williamsburg considered for restoration; preliminary sketches were drawn by the Boston architects, Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, in the fall Jan-May of 1927.

Archaeological investigation of the building, its foundations and the surrounding area was begun by the architectural staff in 1928 and continued in the spring of 1929. Prentice Duell, a consulting archaeologist, completed the excavation and analysis during the summers of 1929 and 1930.

[West (quadrangle foundation archaeo date? 1950]

Several factors influenced the decision to restore the Wren Building to its second form. The determining reason was expressed by the building committee of the College's Board of Visitors on January 2, 1929: Page 10

The Committee feels that inasmuch as the building as it exists today was just completed as a whole in 1732 (when the Chapel was completed) and as there is little authentic evidence of its actual appearance prior to 1705 and that considerable documentary evidence of its condition between 1705 and 1859 does exist it feels justified in its desire to set the restoration date as of 1732.6

The architects were able to authenticate the exterior appearance of the Second Building with great accuracy. The original walls themselves were primary evidence. Besides extensive historical documentation, including detailed descriptions of the building, several valuable pictorial records were available. Outstanding among these were:

- Theodorick Bland Survey Map of Williamsburg, 1699

- Franz Ludwig Michel's Drawing, ca. 1702

- Portrait of Reverend James Blair, ca. 1735-40

- Bodleian Copperplate, ca. 1740

- Plan for Addition by Thomas Jefferson, ca. 1772

- Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg, ca. 1782

- Rochambeau Map of Williamsburg, ca. 1782

- Thomas Charles Millington Watercolor, ca.1840

- C. L. Ludwig Lithograph, ca. 1840

- A Daguerreotype, ca. 1856

- Mary F. Southall's Drawing, ca. 1856 (Little Girl's Drawing) [young lady's?]

Less positive information pertaining to the interior was found. The best guide to the arrangement of rooms was Jefferson's plan which, however, was made over a half-century after the Second Building was finished and showed only the first floor. A drawing of the dormitory room supposedly occupied by John Randolph of Roanoke when he attended

ILLUSTRATION - THE ROOM FORMERLY OCCUPIED BY JOHN RANDOLPH, OF ROANOKE, AT WILLIAM AND MARY'S COLLEGE, VIRGINIA

ILLUSTRATION - THE ROOM FORMERLY OCCUPIED BY JOHN RANDOLPH, OF ROANOKE, AT WILLIAM AND MARY'S COLLEGE, VIRGINIA

DRAWING PUBLISHED IN FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER ON AUGUST 17, 1866

Page 11

the College (1792-1793) was found in the August 17, 1866 edition of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. The reliability of the picture was questionable, although it was the only professed illustration of a room in the Second Building.

Many interior features and details were, of necessity, conjectural restorations. Where documentary proof was limited or lacking, designs were based on known local examples of the period and on English prototypes. A practical adaptation of the floor plan was devised; clues to the original interior arrangement were few and almost nothing was known of the rooms on the second and third floors. The College moreover, urgently needed classrooms and offices. Deference to tradition, was an influential consideration: by custom every William and Mary student attends at least one class in the Wren Building, so the requisite classrooms had to be provided. Facilities essential to the College's function, such as electrical, telephone, heating and sanitary equipment were installed. A fire protection system and fire fighting equipment were also added. Stairways not fully justified by evidence were included as concessions to fire regulations and convenience.

The question of interior restoration was renewed in 1966. Through an agreement with the College of William and Mary, Colonial Williamsburg obtained permission to restore six rooms in the Wren Building to their probable eighteenth-century appearance. Allowance was granted to air condition the entire building and to exhibit publicly -- on an annual basis -- the six restored rooms.

Historical research of the Wren Building was exhaustively reviewed with concentration on the interior appearance of the Second Building.

THE FOURTH COLLEGE BUILDING

PHOTOGRAPH, 1870s

THE FOURTH COLLEGE BUILDING

PHOTOGRAPH, 1870s

(Note Brickwork Repairs)

Page 12

Contemporary English and colonial schools were also investigated in search of analogies and precedent. The period of interior restoration was selected to represent the years 1716-1779. After 1779 the curriculum of the College (as stipulated by the Charter) and the usage of rooms in the Wren Building were somewhat modified; the Grammar School was abolished for a time and the Great Hall ceased to function as a dining hall or refectory. The original uses of five rooms chosen for restoration are certain; the designation of the Common Room, in its restored location, is conjectural, though highly probable.

On July 1, 1968 the restored areas of the building will be opened under the auspices of Colonial Williamsburg's expanded exhibition program. Exhibition of the Wren Building is possible only through the courtesy of the College of William and Mary. The structure will continue to serve pre-eminently the scholastic purposes for which it vas conceived.

CONDITION:

The exterior brick walls, several interior walls in the basement and first floor, and the vaults under the Chapel are the only original portions of the existing building. The original brickwork in the east block and north wing dates largely from ca. 1716, though sections remain from the seventeenth century. The Chapel walls are extant from the period 1729-1732 and the vaults are of subsequent dates. Most of the interior walls and all of the chimneys that survived the fire of 1705 fell in the 1859 conflagration. The walls are preponderantly eighteenth-century, though many areas were patched, altered and repaired during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. (See: marked photostats) Much of the non-original brickwork is concentrated Page 13 around the windows and doors. During the restoration, all post-colonial brickwork was replaced with bricks fired in Williamsburg especially to match the original bricks.

The east block and three two sides of the north wing are laid up in English bond. (Five courses on the south side of the front pavilion and eight courses on its north side, directly above the water table, are laid in Flemish bond.) The west wall of the north wing and the walls of the Chapel have Flemish bond brickwork, liberally decorated with glazed headers. Below the water table, all the foundation walls are laid in English bond. In the east block and north wing, the original walls are 3' thick at the foundation, with footings projecting three-inches on either side; 2' 4" thick on the first floor; and 2' thick on the second floor. The third floor thickness of the main portion's west wall is 1' 8". The Chapel walls are uniformly 2' 9" thick for their full height.

At the time of restoration, the walls were found in relatively poor condition, having been severely warped and cracked by fire and age. Behind the facing were large quantities of salmon, or inferior bricks, commonly used in the eighteenth century to complete wall thicknesses. Compounding the weakness incurred during disaster and time, it was discovered that none of the exterior walls had been plotted at precise right angles when built.

The condition of the walls posed an unusual engineering problem. A unique structural system was devised to insure the permanent preservation of the greatest possible amount of original brickwork. The engineering solution resulted in one of the earliest examples of modern curtain wall construction in Wmsbg. By means of steel beams and concrete footings, the exterior brick walls were supported independently of the interior framework. A Page 14 separate steel frame bears the three-story interior load. The two frameworks were tied together with pliable connectives at intermittent points, allowing flexibility for expansion and contraction and at the same time firmly stabilizing the structure. The exterior walls were entirely relieved of structural weight.

The construction of the roof was complicated by the irregularity of the walls. The roof framing and the cornice had to be adjusted to the warping of the walls. Though there are virtually no plumb lines in the building, it nonetheless gives a symmetrical appearance.

THE FIRST BUILDING (1695-1705)

The First College Building "was intended to be an intire Square, when finished,"7 but only two sides (the east block and the north wing) were built. Financial deficits and political dissensions crippled the building effort so that construction was protracted over five years (1695-1700).

From the beginning the work was approached in stages; there seems to have been little optimism that more than one-fourth of the quadrangle would be erected in the first phase of construction. Examination of the brickwork during restoration revealed that the north wall of the north wing was not bonded into the north wall of the main block. This condition intimates that the two portions were not put up simultaneously or premeditated as an initial unit. Evidently, a fortuitous and unforeseen circumstance enabled the builders to proceed beyond the east block and achieve an L-shaped building in the first period of construction.

The origin of the design is unknown, though the first building was allegedly "modelled"8 by Sir Christopher Wren. Presumably the plans were drawn in England, for it seems unlikely that the Virginia colony had

THE FIRST COLLEGE BUILDING OUTLINE ON SURVEY MAP OF WILLIAMSBURG MADE BY THEODORICK BLAND IN 1699.

ACCORDING TO BLAND, "THE BLACK LINES REPRESENT THE BUILDING

ALREADY ERECTED, THE PRICKT LINES THAT PART WHICH IS TO BE BUILT."

Page 15

a designer of requisite ability. Whether Wren can be credited as architect is disputable (See pp. 78-85). Whoever the architect, his plans were changed. Hugh Jones noted in 1724 that the design was "adapted to the Nature of the Country by the Gentlemen there."9 The Reverend James Blair, President of the College, charged that Governor Nicholson had "shamefully spoilt" the building by making (among other things) "several unnecessary additions of his own invention."10

THE FIRST COLLEGE BUILDING OUTLINE ON SURVEY MAP OF WILLIAMSBURG MADE BY THEODORICK BLAND IN 1699.

ACCORDING TO BLAND, "THE BLACK LINES REPRESENT THE BUILDING

ALREADY ERECTED, THE PRICKT LINES THAT PART WHICH IS TO BE BUILT."

Page 15

a designer of requisite ability. Whether Wren can be credited as architect is disputable (See pp. 78-85). Whoever the architect, his plans were changed. Hugh Jones noted in 1724 that the design was "adapted to the Nature of the Country by the Gentlemen there."9 The Reverend James Blair, President of the College, charged that Governor Nicholson had "shamefully spoilt" the building by making (among other things) "several unnecessary additions of his own invention."10

Whatever the derivation of the design, substantively, much of the building did come from England. Workmen were brought to Virginia specifically to implement the construction. An Englishman, Thomas Hadley, was appointed surveyor, or overseer, of the work. English brickmakers, bricklayers (George Cryer and Samuel Baker), carpenters (Robert Harrison, head carpenter), sawyers and laborers worked under Hadley's direction. When the building was finished, most of these men returned home.

Building materials, including paving stones, glass, and hardware, were imported in large quantities. Much of the collegiate furniture was purchased from English merchants; Micajah and Richard Perry of London served as principal agents. (If it is assumed that Wren was the architect of the building, it might be speculated that he also designed some of the college furniture. Such was occasionally his procedure when engaged for English collegiate designs. Examples of his furnishings are found, for instance, in the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge University, dating from 1677-1699.)

Page 16The fundamental building supplies were obtained in Virginia. The bricks were burned on the site. Remains of the kilns were discovered by archaeological excavation in 1928 and 1929. The kilns, originally averaging about 25'-30' in length, were located at the southeast corner of the rear courtyard and southeast of the Chapel. (It is suspected that the kilns occupied the whole area where the Chapel now stands.) Besides the bricks, oyster shells for lime mortar and plaster, timber (mostly pine), shingles (either cedar or cypress) and the interior woodwork were supplied locally, in large part perhaps from the College lands. The quality of wood used in finishing the building was sharply criticized by James Blair. He felt that the structure was seriously impaired "partly by the Plank & timber being green & unseasoned & partly by employing a great number of unskilled workmen."11

Impediments to the construction continually emerged. James Blair, in a letter to England, outlined some of the major and typical hindrances encountered:

Virginia 21st January (1696/7?)

As to the Coll. the early Winter took us before there was a shingle layd upon it; so that That is dealyd till the spring. The main Timbers are up; but the Roof could not be finished, because the Chimneys which are to go up through it, are not yet carryed up for want of Bricks, & by reason of the unseasonableness of the Weather, to lay them if we had them. Mr. Hadley (A) has been out of the Service of the Coll. about two months ago. The Work is like to meet with a full stop for want of money; for the building hath already exhausted Page 17 what money we had either in Mr. Perrys &c. (B) their hands; or in Col. Birds: (C)and of this Country will come in: most people shifting the payment, & shew plainly that they intend not to pay, unless the Law compel them...12

Despite the many encumbrances, the building was partially in use by 1699 and completed in 1700. A survey map of Williamsburg, made by Theodorick Bland in 1699, shows an outline of the First Building, differentiating the completed sections from the parts unfinished. Bland's notation on the map states that "The black lines represent the building already erected, the prickt [dotted] lines that part which is to be built."13

Robert Beverly described the accomplished work in his book, The History and Present State of Virginia, published in London in 1705:

The Building is to consist of a Quadrangle, two sides of which, are yet only carried up. In this part are already finished all conveniences of Cooking, Brewing, Baking, &c and convenient room for the Reception of the President, and Masters, with many more Scholars than are as yet come to it; in this part are also the Hall, and School-Room.14

One picture of the First Building is known to exist. A French Swiss traveler, Franz Ludwig Michel, visited Williamsburg briefly in 1702 and recorded in his journal observations on the town, its inhabitants and its buildings. The original manuscript has been lost, but a copy made by Michel's brother contains a tinted, crudely sketched drawing of the College. Though it depicts just the east front, the drawing -- along with Michel's commentary -- clarifies many architectural features of the structure.

[(see: A.V. Library - Color prints from Michel journal obtained by Jean Sheldon after this report written.)]

A fairly clear impression of the First Building can be pieced together from the various sources. The east range was

"THE COLLEGE STANDING IN WILLIAMSBURG IN WHICH THE GOVERNOR HAS HIS RESIDENCE, 1702"

"THE COLLEGE STANDING IN WILLIAMSBURG IN WHICH THE GOVERNOR HAS HIS RESIDENCE, 1702"

Page 18

137'6", long and 46' wide; the north wing measured 64' x 32'. The east block rested on a high basement, had three full stories and a half-story beneath the roof, and was crowned with a two-story cupola. The basement story looked much taller than it does today because the original grade has been raised about three feet since the seventeenth century. The exterior brick walls were twenty-seven inches thick on the first floor (the thickness was graduated from foundation to roof) and they rose to a full height of 46'. The walls of the north wing were only 32' high, encompassing two-and-a-half stories. Below the water table the walls were laid in English bond, above that point the pattern was possibly Flemish bond. A moderate scattering of glazed headers adorned the brickwork. The size of the seventeenth-century bricks was 9"-9- ½" x 3-¾" - 4-¼" x 2-¼" - 2-7/16". Michel's drawing shows faceted stone or, rusticated stucco on the foundations and frieze. No physical evidence supports such a treatment, nor is there any recorded mention of it. The stylized blocks under the roof eaves probably represent interstices between cornice modillions, but there is no explanation for the foundation facing. String courses of gauged brick demarked the three stories of the east block. The building must have had at least seven chimneys, though Michel's sketch shows only six. The chimneys, laid up in a faulty manner, caused considerable hazard and inconvenience in the First Building. (See Appendix I) The steeply pitched, shingled roof was pierced with dormer windows and, in the center, topped with the cupola. Lead gutters were mounted along the roof line.

The main entrance was in the center of the east elevation on the basement level; its arched doorway was approached by a long flight of stone steps and surrounded by a balustrade. On the second floor and from the roof, balustraded balconies projected directly above the entrance platform. Michel counted three balconies on the front, obviously including the entrance porch as one. Ranged on either side of the middle bay were three tiers of twelve windows, six on either side. (Michel showed only ten windows in each story.) The number and placement of dormers and basement windows would have corresponded to the windows in the body of the building. The central dormer window was oversize, giving access to the balcony on the roof. All windows certainly had casement sash. Vertical sliding sash with rectangular panes were introduced in England around 1685, but there is little chance that the innovation was used in the First College Building. Side doors to the east block were located near the west corners of the north and south ends. In addition, the ends had two first floor windows and three windows in the second and third stories. The side walls of the north wing had five arched window openings exactly like those in the Second Building. Basement windows were aligned below the larger windows. The west end of the wing corresponded in arrangement to the Second Building: a large, central arched doorway with double doors was flanked on either side and overhead by a rou[nd] window. A piazza with open arches on the outside, extended across the entire west elevation of the main block.

Page 20The interior arrangement closely resembled the plan of the Second Building, with two notable exceptions. One disparity was the placement of the entrance lobby, which was in the basement of the First Building. The main stairway was, moreover, "in ye Middle of ye pile"15 in the First Building. Stairs led from the basement lobby to the first floor middle room, where the "great stairs" were located. The "Stair head" on the second floor was described as being in the "Passage" outside the Convocation Room.16 The location of the stairway accounts for the placement of doors near the west corners of the first and second floor center halls. It also explains the absence of a basement brick partition under the south hall of the Second Building's stair passage (the room south of the center hallway). The kitchen serving the College, following Italianate styles, was originally in the basement, as were all the domestic conveniences and servants quarters.17 A well was located in the northeast corner of the basement. President Blair's living quarters were on the first floor in the two roomssouth corner room? See: depositions after fire ([illegible]Col. Hill south of the stair passage. The "School-Room" (Grammar School) was on the north side of the stair hall. It had two entrances: a folding or double door at the southwest corner and another door "next to the North end."18 The northeast and southeast (corner) rooms on the first floor were classrooms. The "great room" (Great Hall) occupied the entire floor area of the north wing and was two stories high. The Great Hall served both as a dining hall and Chapel. It was sometimes called "the public hall" and in the French edition of Robert Beverly's book (the first edition, published in 1705), it was termed "the refectory". Page 21 Across its west end was poised a gallery, through which "a pair of back stairs" or "private stairs" led up to "the northmost Chamber in ye very roof".19 That upper floor over the Great Hall was a student lodging. The second floor of the east front was subdivided into classrooms, meeting rooms and, most likely, dormitory rooms for the students and apartments for the masters. The Convocation (Blue) Room was situated directly over the School-Room. Above the piazza was a long hall. The Library was apparently on the second floor, though its location has not been ascertained. One room in the building was set aside for philosophical apparatus, but the room in which that equipment was kept is also uncertain. The third story and "the rooms under the roof" were designated student dormitories. One master spoke in 1705 of obtaining the "Porch Chamber" for his servant, but the object of his reference has not been deduced.20 The average dormer in Michel sketch

The interior of the First Building was plastered and the important rooms were probably panelled in some way. The floors would have been uniformly boarded with yellow pine, except in the basement where paving stones were used.

On October 29, 1705 "about 10 a clock at Night, in a publick Time"21 the College caught fire. "the building, Library and furniture" were "in a small time totally consumed."22 The cause of the fire was mysterious never discovered, though there was a notorious blackness about the chimney in the President's room (President Blair was away at the time and his apartment was being occupied by a member of the Council). and arson was whispered Apparently a fire in the dirty and poorly constructed chimney ignited the blaze.

THE SECOND BUILDING (1710-1859)

Four years elapsed before arrangements were made to rebuild the College. The visitors and governors deliberated at length over the advisability of maintaining the walls, but they "at last determined to build the college on the old walls and appointed workmen to view them and [compute] the charge."23 Two months later, on October 31, 1709:

The committee met to receive proposals for the building the College and Mr. Tullitt undertook it for £ 2,000 provided he might wood off the College land and all assistants from England to come at the College's risk...24

When Governor Alexander Spotswood arrived in Virginia in June, 1710, the work was little advanced. The new governor, an amateur architect, took avid interest in the reconstruction and lent it contribution and impetus. Hugh Jones wrote in 1724 that the Second Building was "rebuilt and nicely contrived, altered and adorned by the ingenious Direction of Governor Spotswood ."25

As was the case in the first structure, many building products, furnishings and workmen were imported brought from England. The fundamental supplies were Virginian raw materials. Because of financial exigencies, the second project was no more ambitious than the first effort: two sides of the planned quadrangle, the same east range and north wing, were built. The Second Building was finished between ca. 1716-1718.

Hugh Jones' description of the structure is the most illuminating contemporary account:

The Front which looks due East is double, and is 136 Foot long. It is a lofty Pile of Brick Building adorn'd with a Cupola . At the North End runs back Page 23 a large Wing, which is a handsome Hall , answerable to which the Chapel is to be built; and there is a spacious Piazza on the West Side, from one Wing to the other. It is approached by a good Walk, and a grand Entrance by Steps, with good Courts and Gardens about it...26

When the College was transferred from the Trustees to the President, masters and Professors in 1729, the Second Building was described as:

... more convenient than before, and is now fitted with a hall, and convenient apartments for the schools, and for the lodging of the President, masters, and scholars, and hath in it a convenient chamber set apart for a Library, besides all other offices necessary for the said College, and is adorned with a handsome garden.27

Because the old walls were reused, there were few alterations to the basic plan. The facade of the Second Building differed substantially, however, from the east front of the first. Some of the outstanding dissimilarities between the two versions of the structure were:

28

- 1.Height of the Walls : Probably because of damage to the brickwork, the east block of the Second Building was reduced to two-and-a-half-story height on the front and sides. The interior brick wall on the east side of the piazza protected the outer west wall from serious damage in the fire of 1705, so it was left as its former three-story height.

- 2.Roof : The disparity between the heights of the front and rear walls of the east block would have caused asymmetry in the east and west roof slopes; consequently the east range was covered with a hip roof on three slopes and with a series of six transverse hip roofs across the west side.

- 3.Pavilion : The lowering of the east elevation called for a feature to emphasize the front and relieve the long horizontal expanse. Probably at Spotswood's influence, a focal, projecting pavilion, two-stories high, was raised at the center of the east elevation. It was surmounted with a symmetrically correct, though stiff, right-angle classical Page 24 pediment.

- 4.Cupola : Replacing the First Building's two-story cupola or "high tower", a one-story hexagonal cupola, topped with a weathervane, was added to the Second Building. Its design, too, probably originated with Spotswood.

- 5.Gutters : The First Building bad lead gutters. It would seem logical that the Second Building had ground level brick gutters, but insufficient archaeological evidence of these was found. Wood gutters at the roof eaves were probably installed. cornice gutters used to protect walls from erosion see p. 11, Vol. II Bricks (illegible) brick butter (North) I

- 6.Drainage : Drainage was a problem in the First Building; water did not run off from the building properly and often stagnated around the structure and in the basement. This condition was rectified in the Second Building by a drainage system that emptied from the front to the back of the building via the basement. The yard was also regraded.

- 7.Entrance : The grade in front of the Second Building was raised about a foot and a half and the main entrance was placed on the first floor level.

- 8.Position of Staircase : The center stair passage doubtless provided an excellent flue for the fire which gutted the First Building. For that reason, and perhaps for aesthetic considerations, the main stairway in the Second Building was moved to a separate stair hall, in the room south of the entry.

- 9.Sash and Glass : Apparently vertical sliding sash were used in the Second Building, instead of the diamond-paned casements that appeared in the First Building. "Sash Glass" was ordered for "the Colledge Hall" on October 24, 1716. Spare glass was also written for "to repair the windows of the Colledge."

The interior arrangement of the Second Building closely paralleled the floor plan of the first structure, except for the position of the main staircase. President Blair's apartment was again on the first floor, probably in the room south of the re-located stair passage. It was certainly after Blair moved into the newly completed President's House (1733) that the southeast middle room vas converted to the Writing Schoolroom (its designation on Jefferson's floor plan). The southeast corner room was

Page 25

used for a short period in 1716 by William Levingston for his dancing school. Later it was assigned to the Professor of "Physicks, Metaphysicks and Mathematicks" (natural philosophy and mathematics) who was one of two professors in the Philosophy School. Possibly some of the philosophical apparatus was housed in that southeast room. By the time of the Revolution there was a specifically allocated "Apparatus-Room," but its location is uncertain. The other professor in the Philosophy School, the Professor of Moral Philosophy who taught "Rhetorick, Logick and Ethicks", lectured at the opposite end of the east range. His classroom was in the northeast corner on the first floor. The Grammar School Room, Piazza, Great Hall and Convocation (Blue) Room were exactly as they had been in the First Building. The Library and the Common Room (used by the President, Masters and college officials for social gatherings) were on the second floor. Student dormitories were on the second floor and in the rooms under the roof. Apartments for the masters and ushers were likewise on the upper floors. A letter dated March 26, 1765 from Stephen Hawtrey to his brother, Edward, (a prospective professor) concerned the accommodations he could expect at William and Mary:

You have two rooms -- by no means elegant tho' equal in goodness to any in the College -- unfurnished & will salute your Eyes on your Entrance with bare plaister Walls -- however Mr Small assures me they are what the rest of the Professors have & are very well satisfied with the homliness of their appearance tho' at first rather disgusting -- he thinks you will not chuse to lay out any money on them.29

THE SECOND BUILDING - WEST ELEVATION

ENLARGEMENT FROM THE BODLEIAN COPPERPLATE ca. 1740

THE SECOND BUILDING - WEST ELEVATION

ENLARGEMENT FROM THE BODLEIAN COPPERPLATE ca. 1740

In the late eighteenth century some of the second floor rooms were devoted to classrooms and student society rooms. The kitchen remained in the basement, though the Bake-house and Brew-house were installed in outbuildings. The oven had been removed outside before the fire of 1705. Meals were not served in the College after 1779, so with the cessation of boarding, the kitchen was no longer needed. no outside kitchen?

Between 1728-1732 the third side of the quadrangle was erected. Henry Cary was appointed undertaker, or contractor, for the construction of the Chapel, the southwest wing that was "answerable"30 to and built "in [the] form of"31 the Great Hall. The most explicit and detailed description of the chapel interior is found in a letter from Lord Botetourt's executors to the Duke of Beaufort, nephew and heir of the governor. Botetourt was buried in the College Chapel on October 19, 1770; the letter concerned a memorial monument the nephew wished to erect over his grave:

Virginia 27th May 1771.

My Lord Duke.

...The Monument cannot be conveniently erected over the Grave as it would spoil two principal Pews & incommode the Chapel considerably in other respects.

If it is proposed to have it in the form of a Pyramid, it can be placed conveniently in no part, except at the Bottom of the Isle fronting the Pulpit, where it would appear to advantage, if the Dimensions should not be thought too much confined; the Isle itself is about ten feet wide; there must be a Passage left on each side of the monument at least two feet & an half so that the width of the monument, which will form the Front can be no more than five feet.

A flat monument may be fixt still more commodiously in the side of the wall nearly opposite to the Grave. Page 27 Between two large windows, there is a strong brick Pier six feet and an half wide; the length of this pier from the ceiling down to the wainscot is twelve feet and an half, & from the Top of the wainscot to the floor eleven feet and an half more; if the Height from the Wainscot to the ceiling should not be thought sufficient, we suppose there would be no Inconvenience in letting the monument down into the wainscot as low as the Floor, but then the bottom Part of it would be hid by the Front of the Pew.32

While arrangements were underway to mark the spot of Botetourt's interment with a suitable monument, his successor, Lord Dunmore, was initiating an enlargement of the College. In 1771 or 1772 Thomas Jefferson, at the governor's request, drew plans for the long-delayed completion of the college square. The addition, as shown on Jefferson's drawing, would have achieved an enclosed rectangle rather than the smaller quadrangle that was planned in 1695. Bids were let in the fall of 1772 and evidently construction was begun soon thereafter. Foundations for the west side were laid and building materials (nails and scantling) were purchased. The work came to no greater fruition, though, for the Revolution put an end to it. The foundations were still visible in 1777 when Ebenezer Hazard, a traveler from the North, noted in his journal: still visible in 1859? see p. 8

... there is also the Foundation of a new Building which was intended for an Addition to the College [opposite the Piazza], but has been discontinued on Account of the present Troubles ... 33

The foundation bricks were later salvaged when it became apparent that the quadrangle would not be finished for lack of funds.

Few changes were made to the fabric of the building through Page 28 the rest of the eighteenth century. The usages of certain rooms were discontinued or rearranged, but not until the nineteenth century were extensive repairs and alterations financially feasible. The interior was greatly refurbished and the roof was reshingled during 1855-1856. When the Second Building burned on February 8, 1859, its original interior characteristics had been appreciably transformed, but the exterior looked much as it did ca. 1732.

PICTORIAL RECORDS OF THE SECOND WREN BUILDING:

EAST ELEVATION:

- Portrait of James Blair, 1735-1740 [ca1735] (Blair died 1743)[Mr. M. Godwin]

- Bodleian Plate, after 1733, ca. 1740

- Painting by unknown artist, ca. 1820

- Millington Watercolor, ca. 1840

- C. L. Ludwig Lithograph, ca. 1840

- Daguerreotype, ca. 1856

- Little Girl's Drawing, ca. 1856 (Mary F. Southall)

WEST ELEVATION:

- Bodleian Plate

- Little Girl's Drawing

SOUTH ELEVATION:

- Bodleian Plate

- Blair Portrait

NORTH ELEVATION:

- None

FLOOR PLAN:

- Jefferson's Plan, ca. 1771-1772

OUTLINE:

- Theodorick Bland Survey, 1699

- Frenchman's Map, ca. 1782

- French Billeting Maps (Rochambeau, Capitaine)

- 19th-Century Maps (Bucktrout, College, Galt, Brown)

INTERIOR:

- John Randolph (of Roanoke) Room, (1792-1793); published FRANK LESLIE'S ILLUSTRATED NEWSPAPER, August 17, 1866

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY - SECOND BUILDING

THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY - SECOND BUILDING

ENLARGEMENT OF BACKGROUND DETAIL

IN

PORTRAIT OF THE REV. JAMES BLAIR

ATTRIBUTED TO CHARLES BRIDGES

ca. 1735-1740

THE SECOND BUILDING

THE SECOND BUILDING

ENLARGEMENT FROM THE BODLEIAN COPPER PLATE

ca. 1740

DESIGN:

The restoration architects termed the style of the Wren Building (the second structure) a medieval form, "typical of the middle English Renaissance."34 When the College in Virginia was begun, its proposed quadrangular plan was several centuries old as an English collegiate pattern. Had the design been executed, the College building would have been the first quadrangle in British America. Inadvertently, the Wren Building became the harbinger of a new collegiate type American; its open, U-shaped plan was one of the earliest examples in the colonies of the transition from court to campus. In another way, the Wren Building exemplified a new colonial building type. It established a style suitable to its function, departing from the domestic form that, until then, had been adapted for public structures.

The Wren Building has been compared to several coeval structures, but no actual source or unqualified prototype has been found. Its basic inspiration was akin to the buildings at Oxford and Cambridge and numerous other English universities and schools. English collegiate designs Hugh Jones wrote that it was "not altogether unlike Chelsea Hospital"35 in London, designed by Wren and begun in 1682. Its initial plan closely resembled Heriot's Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland (1628-1650), a school for orphans. Also analogous was Codrington College in the Barbados, designed by Christian Lilly in 1713 and imitative of Chelsea Hospital. The Wren Building's west elevation (rear) bears a superficial relationship to Arlington House in England (1700). Under Governor Spotswood's influence, the Second Building acquired certain motifs and

THE SECOND FORM OF THE WREN BUILDING

THE SECOND FORM OF THE WREN BUILDING

A DAGUERREOTYPE

ca. 1856

CHELSEA HOSPITAL, LONDON

CHELSEA HOSPITAL, LONDON

VIEW FROM THE SOUTHEAST ca. 1700

Page 31

the regularity associated with classical themes in architecture. As Marcus Whiffen concluded, however:

It would be a mistake to try to affix any stylistic label too firmly to the second College building -- as indeed to much English building of its time. Nor would a search for specific prototypes be a profitable occupation.36

The traditional claim that Sir Christopher Wren designed the main building of the College of William and Mary has tacit approbation in the persistent use of his name for the structure. The attribution, however, has dubious historical support. Some of the arguments raised over the contention are enumerated in Appendix II.

THE COLLEGE ENVIRONS:

Before the main building of the College vas erected, only one sizeable structure [Blair's House] stood near its site. That was "the little School-House close by it,"37 described as the one "fit house upon the place."38 The Grammar School students were educated there from ca. 1694-1700 and President Blair, the schoolmaster and the scholars lived in it until the Wren Building was finished in 1700.

When its foundations were laid, the east front of the Wren Building was oriented along a due north/south line. Hugh Jones noted that the structure was disposed at a latitude "37° 21' North".39 Williamsburg's central axis, the Duke of Gloucester Street was plotted in 1699. It was laid out by compass on an east/west line that tilted slightly to the north. Consequently, the Wren Building did not front squarely on the long avenue.

The Wren Building was situated less than a quarter of a mile from Bruton Parish Church. By 1705 there were a tavern and several

ARLINGTON HOUSE, ENGLAND

1700

ARLINGTON HOUSE, ENGLAND

1700

[a previous building on site of Buckingham Palace]

Page 32

houses (one belonging to President Blair) not far from the College and a cluster of buildings had sprung up in the vicinity (stores, gentlemens' houses, ordinaries, and inns). The Capitol stood at the opposite end of Duke of Gloucester Street. A quarter of a century elapsed, however, before any buildings of consequence arose in proximity to the College edifice.

During the 1720s and 1730s the College flourished in a period of architectural expansion. The Chapel was finally appended to the Wren Building. An endowment for the foundation of an Indian School (Robert Boyle's legacy) enabled the construction of the Brafferton in 1724. The structure was an imposing, two-story, brick house, situated immediately southeast of the Wren Building. The complement to the Brafferton was erected in the College yard during 1732-1733, when the President's House was built opposite the Indian schoolhouse at the northeast corner of the main building. It was also a handsome two-story, brick dwelling, similar, but not identical, to the Brafferton. The arrangement of the three structures was slightly uncoordinated. The Brafferton had been placed exactly parallel to Duke of Gloucester Street, whereas the Wren Building was not perpendicular to the main street. To diminish the irregularity of the east composition, the President's House was set at right angles to the Wren Building. The deception was successful for, in the end, a seemingly balanced frontal effect was achieved. When the Chapel and flanking buildings were finished, the eighteenth-century architectural development of the College was brought to culmination.

THE WREN BUILDING (CENTER), THE BRAFFERTON (LEFT) AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE AS THEY APPEARED ABOUT 1740 (FROM THE BODLEIAN PLATE).

THE WREN BUILDING (CENTER), THE BRAFFERTON (LEFT) AND THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE AS THEY APPEARED ABOUT 1740 (FROM THE BODLEIAN PLATE).

The College and its appurtenances were described in 1724:

It [the main building] is approached by a good Walk, and a grand Entrance by Steps, with good Courts and Gardens about it, with a good House and Apartments for the Indian Master and his Scholars, and Outhouses; and a large Pasture enclosed like a Park with about 150 in acres of Land adjoining for occasional Uses.40

In August, 1732 William Dawson wrote to the Bishop of London:

The foundation of a common brick House for the President was laid opposite to Brafferton [on July 31]... These two buildings will appear at a small distance from the East front of the College, before which is a Garden planted with evergreens kept in very good order. The Hall and Chapel, joining to the west Front towards the Kitchen Garden form two handsome wings...41

The Bodleian copperplate (ca.1740) illustrates the east perspective of the College, showing clearly the features of the yard. Rows of topiary plantings surrounded grassy plots and lined the walks approaching each building. A low fence extended from either side of the Wren Building and returned to enclose the side and rear yards. Fence gates were located opposite the north and south end doors of the main building.

The surroundings changed little over the ensuing forty years. Two references from the 1770s echo earlier descriptions:

The college makes a very agreeable appearance, and the large garden before it, is of ornament and use...42

Ebenezer Hazard, the Northern traveler, noted in 1777:

At this [east] Front of the College is a large Court Yard, ornamented with Gravel Walks, Trees cut into different Forms, & Grass ... [On the west front] opposite to this Parade [the Piazza] is a Court Yard & a large Kitchen Garden ...43

[DETAIL FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP]

[DETAIL FROM FRENCHMAN'S MAP]

The Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg (ca.1782) corroborates accounts of the College layout. It depicts a large enclosure, probably fenced, to the west of the Wren Building. This was undoubtedly "the Pasture" of 1724 that became "a large Kitchen Garden" by 1777. Four outbuildings were disposed symmetrically between the west enclosure and the main building. The two contiguous to the fence line may have been the "Brew-house" and "Bake-house". Those facilities were moved outdoors from the College basement not long after the completion of the Second Building. The other two outbuildings were probably necessary houses. Apparently fences encompassed three sides of the east yard and the area west of the President's House. A kitchen west of the Brafferton was balanced by the President's House kitchen on the opposite side of the front yard. A stable for the President's use stood at the roadside to the northwest of his house. Dotted markings on the map, presumably representing two double rows of trees, linked the Wren Building to its brick adjuncts. The configurations could not indicate architectural connectives, for it is well documented that the two brick houses were "not joined"44 to the Wren Building. Brafferton) Pres. House) Remote Outbldgs)

Present College Triangle [illegible]

INTERIOR:

Plan