The Public Hospital: An Architectural History and Chronicle of Reconstruction Block 4 Building 11

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0143

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE PUBLIC HOSPITAL:

AN ARCHITECTURAL HISTORY AND

A CHRONICLE OF RECONSTRUCTION

Architectural Research Department

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

1986

VOLUME I

| Page | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Chapter | |

| I The Hospital is Established | 5 |

| II Philadelphia and Williamsburg Design, Construction and Use | 14 |

| III The Building Committee and Construction | 27 |

| IV Plan, Function and Use | 41 |

| V Nineteenth-Century Growth | 53 |

| VI New Directions, 1838-1885 | 58 |

| VII Colonial Williamsburg and Eastern State Hospital, 1928-1969 | 71 |

INTRODUCTION

On the eve of the American Revolution, the Public Hospital "for the Reception of Ideots, Lunatics, and Persons of insane Mind" was constructed in Williamsburg, Virginia. It was the last public building to appear in Virginia's colonial capital. In addition, the building took on contemporary significance as one of Williamsburg's largest structures.

In retrospect, it seems that the reconstruction of the Public Hospital was inevitable. The replacement of significant structures, especially public buildings, has been considered absolutely necessary to fulfill educational goals of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The reconstruction and interpretation of the Public Hospital are essential for presenting a more complete history of Williamsburg in the late colonial era. A mental hospital is, without a doubt, an unlikely institution in the late eighteenth-century social milieu in which Colonial Williamsburg has been portrayed heretofore. The building is also an important example in the chronological development of Williamsburg's architecture and as an example of the work of its architect and builder. A combination of these factors justifies its reconstruction.

The significance of the Public Hospital is derived from a discrete event, though not the usual political or historical happening which characterizes most historic buildings and sites. Its significance lies in its establishment as an institution.

2The Public Hospital claims the honor of being the first hospital in America built expressly for the treatment of the mentally ill. Such a distinction is equal to that of the Capitol or the Palace.

In a very simple manner, a building can be defined as the result of a social need. In the case of the Public Hospital, a new social need resulted in a new building type. As that need changed over time, so did corresponding aspects of the building's form and function. The meanings inherent in this social/architectural interdependence are as elusive as the causes of mental illness. The intended purpose of the building, its intended clients, and its intended architectural image are complicated by the fact that a mental hospital was not a traditional institution in America and its designer responded to a need communicated to him over a long distance. Cross-regional translation of the architectural form resulted in its transformation, being "adapted to the Nature of the Country by the Gentlemen there," as the Wren Building's design had been described in an earlier time. Analytical clarity is further complicated by the fact that the building has been gone for a century now and its original drawings are lost or destroyed. Nevertheless, the means of construction, i.e. local traditional forms and local technology, can be determined by documentary and comparative evidence so that the ultimate function and meaning of the building can be sorted into a contextual perspective and, hopefully, understood.

3Part I of this report treats the architectural history of the building through its establishment, design, construction, evolution and rebirth. Part II is the chronicle of the Public Hospital's reconstruction between 1981 and 1985. This second part is divided into essays or chapters covering each design element. For each element the chapter is arranged into sections comprising description, documentation, prototypes and comments on construction. These sections are further expanded as necessary. Part III covers materials and is organized in a similar manner.

Parts II and III are an attempt to record, as completely as possible, the history of each design decision. In the past, too many CWF architectural reports were written long after the fact and were confined to a post restoration/reconstruction description of the building rather than a record of the decisions from which it was created. Keeping this in mind, this report was written to fill those voids where future questions are likely to rise. It is impossible, of course, to recapture the entire decision-making process because many discussions and exchanges are spontaneous and survive only in short term memory. Therefore, observing the historians' cardinal rule, readers are encouraged to investigate the primary sources for this report: file notes, memorandums, letters, minutes of meetings and site reports. In particular, the minutes of the Design Review Committee and the chronology/site reports are of importance regarding details, and in many cases, the personal, intimate story of the project.

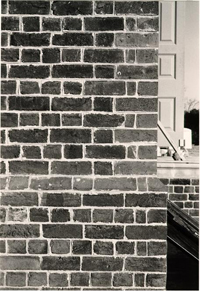

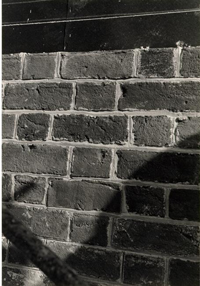

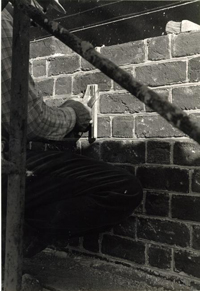

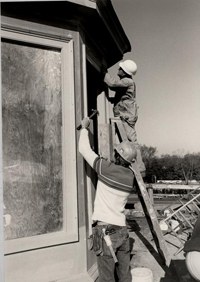

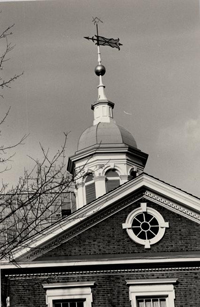

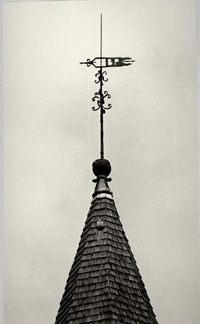

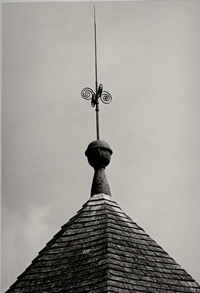

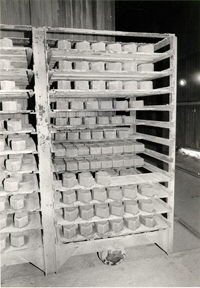

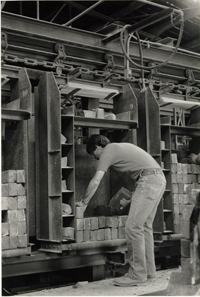

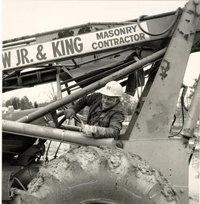

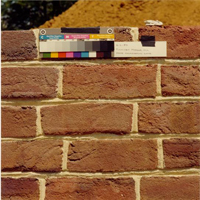

4The pleasures of my involvement with this project have been many. Every project of this scope is unique and no doubt breeds many personal stories of discovery and frustration, victory and defeat. I like to think that those of us who have been actively involved in the project during the past five years will continue to think of the experience as a great one. Working at Colonial Williamsburg in the 1980s era of neo-realism has been exciting. Certain memories remain vivid: two weeks of hand-blending 60,000 bricks in the North Carolina heat; driving all over the countryside in search of the right mortar sand; trudging through muddy Tidewater swamps looking for that ever elusive perfect cypress tree; climbing precarious ladders to erect bamboo weather vanes; learning the quirks of various craftsmen; and last, but certainly not least, spending many hours hashing out some life-or-death inch of a design or construction problem with the best group of colleagues with whom I have ever had the pleasure of working.

CHAPTER I

THE HOSPITAL IS ESTABLISHED

The establishment of the Public Hospital will probably always remain something of a mystery. There are, of course, readily given reasons for its existence, some of which are undeniably clear. The curiosity, however, of why a new type of institution occurs in its particular time and place will be forever begging for those bits of rationale which inevitably fall between the recorded lines of history.

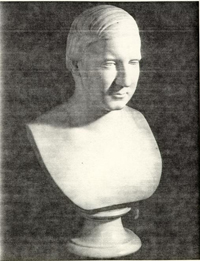

There is no doubt that the founder of the Public Hospital, Governor Francis Fauquier, was a gentleman of considerable intellect and humanism, a man of the Enlightenment (Fig. 1). Unfortunately, Fauquier left no evidence of what specifically led him to propose this new public building to the House of Burgesses in the fall of 1766. The two repeated themes seem to be some concern for the safety of society and affecting a cure for insanity, as mentioned in Fauquier's proposal:

It is expedient I should also recommend to your Consideration and Humanity a poor unhappy set of People who are deprived of their senses and wander about the Country, terrifying the Rest of their Fellow Creatures. A legal Confinement, and proper Provision, ought to be appointed for these miserable objects, who cannot help themselves. Every civilized Country has an Hospital for these People, where they are confined, maintained and attended by able Physicians, to endeavour to restore to them their lost Reason.1

Figure 1

Figure 1

Governor Francis Fauquier, Founder of the Public Hospital. (CWF #67-2033)

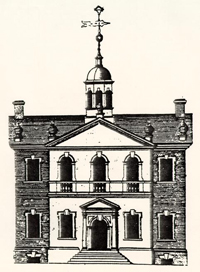

Fauquier knew of general voluntary hospitals in England and he most probably knew Bethlehem Hospital for the insane in London (Fig. 2). Hospitals of any type in America were virtually nonexistent in 1766; there was only one, the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia (Fig. 3). Specialized hospitals did exist in England, Scotland and on the continent, but they were rare even there. Public provision for the insane in colonial American consisted of jails and, in some cases, almshouses for the indigent. However, with the exception of care provided at the Pennsylvania Hospital, no institutional system of treatment existed. If treatment was in evidence at all, it was a private matter for those families who had the means and the desire. Regardless of the reason, the eventual result of Fauquier's effort was not new legislation to ban the homeless insane from public areas, or construct additional jail cells. It was a hospital designed for the confinement, care and treatment of the mentally ill.

When additional encouragement for legislation was needed the following spring, Fauquier considered the hospital of "some importance to the ease and comfort of the whole community, as well as a point of charity."2 Fauquier died before making his proposal for a third time and the issue passed to his successor, Lord Botetourt. Perhaps inspired by a Virginia Gazette editorial of July 6, 1769, which referred to a murder by a lunatic that might have been prevented if a proper place of confinement existed, the House of Burgesses moved closer to enactment on

Figure 2

Figure 2

Bethlehem Hospital, Moorfields, London about 1750. (CWF #84-2764)

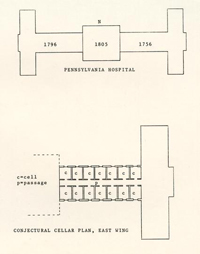

Figure 3

Figure 3

Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, founded in 1755. This illustration was a subscription print. The right wing was constructed in 1756; the left wing dates to 1796; and the central pavilion dates to 1804. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

7

November 15, 1769, when it ordered draft legislation for the hospital. Just prior to this, Botetourt had asked William Byrd III to request the general hospital in Philadelphia to receive four lunatics then confined in the Public Gaol in Williamsburg. The Pennsylvania Hospital, which had set aside its cellar cells for the insane, replied favorably to the request. Upon hearing this, the House of Burgesses passed a resolution thanking Botetourt "for his kind and humane Attention to the Piteous Situation of the four unhappy People, who are disordered in their Senses . . . .3 Both the editorial and the request by Botetourt indicate an awareness and a realization that the issue of mental illness was, to some degree, a social and a public matter rather than a private one. It was not until June 4, 1770, that the burgesses passed a bill to establish the Public Hospital. In enacting the bill, the significant passage in the preamble, in addition to the need for restraint of those "who may be dangerous to society," is the statement that "no provision . . . [has] been yet made . . . towards effecting a cure of those whose cases are not become quite desperate."4 When the hospital opened in the fall of 1773 and began its uncharted course, its trustees emphasized cure, rather than mere confinement. Although security played its part, the desire for cure remains one key to this building's enigmatic beginning and to its medical and social significance thereafter.

ENGLISH VIRTUES

Of all the populated centers in colonial America, Williamsburg seems an unlikely choice for the establishment of an institution like the Public Hospital. After all, Williamsburg was not a bustling urban center with a disproportionately large number of the mentally ill. Virginia as a whole, in fact, had a large, yet dispersed population exceeding that of Pennsylvania, Maryland and Massachusetts. Except for the brief legislative seasons, Williamsburg remained a comparatively small community inhabited in 1770 by about 1500 people. The impetus for establishment, then, seems all important, since the actual need for a hospital in terms of patients did not appear great. In the first few years after its completion, the Public Hospital could not even fill up its first floor of twelve cells. In contrast, the Pennsylvania Hospital reported a rather large number of mentally ill patients in 1770, accounting for about one-third of the total patient population of 135.5 The reasons seem to lie more with the perceived rather than with the actual need. Even though proposed by a royal governor, the Public Hospital was accepted, managed and molded by citizens, albeit gentry, who fashioned themselves after English counterparts. If it is true that Virginia was a colony of "transplanters," a gentry-controlled society wishing to establish English institutions and to "fulfill English virtues," the Public Hospital could have been part of that desire.6 Despite the conceptual or physical 9 prototypes, however, the result was American, as were many other transplanted works. The imposition of a civilizing order on the American wilderness is a common theme in early American history, It is natural for man to create order out of disorder. The College of William and Mary, established in 1693, can be considered an example of intellectual order in a partially tamed wilderness. Similarly, the Public Hospital was a new type of institution for both a disorder in society and those "disordered in their senses." Establishing a "first" institution of any kind amounts to what Anthony King has characterized as a "formal acknowledgment of a change in society's arrangement for meeting a particular social need."7 The Public Hospital represented a change in the "moral boundaries" of the Williamsburg and Virginia communities. It was an age-old cultural problem recognized in a "formal" manner by associating it with a building type which connoted both societal control and medical cure.

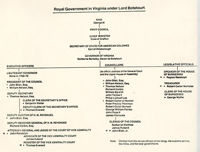

Once established in legislation, the reality of a hospital fell out of the governor's hands and into those of the local citizens. From June 1770 until well into the next century, the hospital was run solely by a Court of Directors made up of selected trustees, the first of whom had been named in the establishing act: John Blair, William Nelson, Robert Carter, Peyton Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas, John Randolph, Benjamin Waller, John Blair, Jr., George Wythe, Dudley Digges, Jr., Lewis Burwell, Thomas Nelson, Jr., Thomas Everard and John Tazewell. These were the men who held political authority and wielded 10 political power (Fig. 4). Members of this group occupied seven out of ten positions on Governor Lord Botetourt's executive officer staff. Among the hospitals' trustees were all three of the colony's legislative officials and four as councillors in the upper house of assembly. These men would have had the confidence of the Governor and would have been early advocates of the need for a hospital, if for no other reason than their enlightened "liberal" sense of social and community responsibility.8

The governor empowered this core group of trustees to choose an unpaid Court of Directors, consisting of a president and six other members, who would administer the fledgling operation of this new institution. To these laymen fell the task of selecting and purchasing a site; directing the construction of a building; selecting a hospital staff; setting regulations for its operation; overseeing many administrative and financial details; and most significantly, meeting frequently to examine and decide who would be admitted or discharged as patients. Beginning on Tuesday, October 12, 1773, the court set every following Tuesday as a time to meet and to receive prospective patients sent by the county magistrates. Sheriffs accompanied the patients and were paid five pounds of tobacco per mile for the trip. If they were necessary, other guards received three pounds of tobacco per mile.

Figure 4

Figure 4

Royal Government in Virginia in 1770. Public Hospital Trustees denoted by ? and Public Hospital Building Committee denoted by +. (Chart by John Hemphill)

EARLY TREATMENT

Both the Act of Assembly and the announcement in 1773 that the Public Hospital was accepting patients mentioned the term "proper objects." "Proper objects" were neither the untreatable mentally retarded, nor the social problems of a community such as paupers, the homeless or alcoholics. But just what was the treatment for those "proper objects" and how did it affect cure?

Although the Public Hospital was actually run by lay keepers until the 1840s, local physicians attended the directors' meetings and treated the patients when necessary. Doctor John De Siqueyra was the first physician on call. Dr. Philip Barraud and Dr. John Minson Galt first assisted De Siqueyra and then succeeded him. Basically, treatment of the mentally ill was little different from the general practice of medicine in eighteenth-century America. There were special forms of treatment used at the hospital, involving both water and electricity, but, for the most part, traditionally-trained physicians practiced the so-called "heroic" treatment according to traditionally held medical theories regarding body humors:

…the functioning of the body and its temperament were governed by four humors, each corresponding to one of the elements that composed the cosmos. There was blood, corresponding to air and tending toward heat and moisture; phlem, corresponding to water and tending toward wet and cold; yellow or green bile (choler), corresponding to fire and tending toward heat and dryness; and black bile (whence the word "melancholy"), corresponding to earth and tending toward cold and 12 dryness. The health of the body depended upon the maintenance of balance in these humors.9There were no specialists for mental illness. That field would not come into being until the mid-nineteenth century. Even the "father of American psychiatry," Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia who foreshadowed the nineteenth-century Moral Management revolution in the treatment of mental illness, maintained his belief in humors with reference to the treatment of the insane. Despite the reliance on medical tradition, American physicians of the eighteenth century, especially those in Virginia, have been characterized as more successful "healers" than their European colleagues. This theory is based on the close association of medical theory and practice in America, a reliance on the apprentice system, and the practical necessity of less extreme forms of treatment.10 As Normain Dain notes in his history, Disordered Minds, patients at the Public Hospital were treated well, if only by virtue of a kind keeper and staff, a small town atmosphere and an attentive group of trustees. By circumstance, then, early care and treatment at the Public Hospital was as good as that available in comparable facilities in Philadelphia and probably better than in many of those described by John Howard in Europe.11

For a much more complete discussion of the administrative and medical history of the hospital the reader is directed to Shomer Zwelling's Quest for a Cure.

CHAPTER I

NOTES

CHAPTER II

PHILADELPHIA AND WILLIAMSBURG:

DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION AND USE

The Public Hospital's architectural history, like the history of its inception, is a combination of rich, well documented facts and plausible assumptions. There is no doubt that the most talented third generation builder-architect of Philadelphia, Robert Smith, designed the Public Hospital. The connection of Smith with Williamsburg is the undocumented and tantalizing part of the story, but it can be well imagined. William Byrd III of Westover is the person easily chosen as the Williamsburg-Smith connection (Fig. 5). Byrd knew Philadelphia through both personal experience and family connections and most likely knew Robert Smith and his work.

PHILADELPHIA CONNECTIONS

It was probably at the request of newly arrived Governor Botetourt that William Byrd corresponded with Mayor Thomas Willing of Philadelphia in 1769 regarding four lunatics in the Williamsburg Public Gaol.1 Willing's letter to Byrd in November 1769 stated that the four lunatics could be accommodated at the Pennsylvania Hospital. After the House of Burgesses secured the Governor's authorization, the "four unhappy people" were taken to Philadelphia the following March.

Figure 5

Figure 5

William Byrd III of Westover by Cosmo Alexandre (Virginia State Library) (CWF #56-CL-403)

Byrd was the logical person to correspond with Willing, having married Willing's sister, Mary, in 1761 (Fig. 6).2 If Robert Smith was not known to Byrd personally, Thomas Willing was, at least, well acquainted with Smith's work. Willing was a trustee of the Old Academy and New College of Pennsylvania, part of which was remodeled by Smith in 1750; he was-a subscriber to Christ Church, whose steeple Smith designed and constructed in 1751-1754; he was also a subscriber to the Presbyterian Church in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, which Smith designed in 1757; and he was a subscriber to the Pennsylvania Hospital, for which Smith was a subscriber and a design consultant.

Still another family connection could have put Byrd in touch with Smith. Dr. William Shippen, a well-known Germantown physician, was the maternal uncle of Mary Willing Byrd. Shippen is directly associated with Smith through the design for Nassau Hall at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), where the trustees approved in 1754 "the Plan drawn by Doct. W. Shippen and Mr. Robt. Smith." Edward Shippen, William's brother and a trustee of the College, mentioned the plan in a letter to his son, who was in school there.3

The other very likely link in this puzzle is Samuel Powel, a wealthy, well educated young man, who was the mayor of Philadelphia at the time of the Revolutionary War. In 1769 Powel, having returned from European travels, married, bought a house and began extensive remodeling work. Powel married Elizabeth Willing, Mary Willing Byrd's sister. Powel's house

Figure 6

Figure 6

Mary Willing Byrd (1740-1814), second wife of William Byrd III. Attributed to Matthew Pratt. (Virginia State Library) (CWF #81-FD-1207)

16

stood on Third Street in Society Hill across the street from Thomas Willing and next to the house William and Mary Byrd had built and lived in from 1761-1764.4 Perhaps most interestingly, Powel employed Robert Smith from 1769-1773 to remodel and finish the interior of his house, during which time Smith provided plans for the Public Hospital.

Robert Smith and William Byrd no doubt had other mutual friends besides the Willing family, but suffice it to say, Smith's reputation would have been assurance that had Byrd inquired after a capable architect, Smith's name would have been mentioned. The fact that Robert Smith's drawings, or at least his "Description" of the hospital, were dated two months prior to the actual act establishing the institution and the appointment of a committee to determine a design, clearly indicates that he had been asked personally to submit a scheme. In all likelihood, Smith was chosen as the designer long before the public call for proposals.

ROBERT SMITH OF PHILADELPHIA

Robert Smith was born into a Scottish family of masons and builders in Dalkeith, near Edinburgh in 1722.5 The name Smith was well associated in the Edinburgh area with the building trade, the most prominent representative being James Smith (16461731).6 James Smith had replaced William Bruce as the leading architect in Scotland and held the position of overseer of Royal Works for thirty-five years. By the time Robert Smith had reached apprentice age, William Adam (1689-1748) had overtaken James Smith as the most prominent Scottish architect. Adam had served his apprenticeship under William Bruce and was the father of four sons, including architects John, Robert and James Adam.7 It is unknown whether Robert Smith actually worked for William Adam or perhaps John Adam, who had taken a greater role in the family business by the 1740s. The opportunity would have been possible, for Adam's business was booming in the 1730s - 40s. Of the many Adam works in the Edinburgh area, two coincide with Robert Smith's apprentice years: Dalkeith House, in his hometown, which Adam was remodeling in 1741-42; and the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, which, although begun in 1738, was not completed until 1748 (Fig. 7). Smith probably emigrated no later than the end of 1748, since his first known American works were the Second Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia in February 1749 and the remodeling of Bush Hill, Governor Hamilton's house, in the same year. Historians have speculated that Smith's emigration is somehow connected to either the death of William

Figure 7

Figure 7

royal Infirmary, Edinburgh by William Adam, 1738-1748. From Adam's Vitruvius Scoticus. (CWF #84-2129)

18

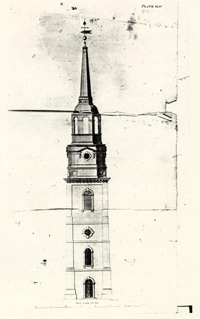

Adam in June 1748 or to Pennsylvania Governor James Hamilton, who had been in London in 1748 to receive the governorship and may have visited family in Scotland.8 In any case, Robert Smith arrived in America well versed in his carpenter trade. Through his earliest known commissions, which included the building and possible design of Philadelphia's Christ Church steeple in 1751, his patrons quickly regarded him as a leading carpenter-architect in that city (Fig. 8).

The last fifty years of Philadelphia's colonial period (1725-1775) have been referred to as a "Golden Age."9 This was the period in which the city witnessed many of its noted cultural achievements, most of which were represented by masterful architectural designs. The second half of this era also encompasses Robert Smith's professional career. Smith certainly did not find Philadelphia an architectural vacuum. Gentlemen-architects and carpenter-builders had designed structures which rivaled England's most fashionable buildings.

Smith's known works can be considered among the best and most competent of those produced by second generation of Philadelphia "architects." They are not, however, extraordinary or innovative; it would be the next, the post-war, generation of builder-architects that would imaginatively expand upon traditional forms. Smith's generation, however, was responsible for the often overlooked role of translating architecture from British colonial to American. Although analysis is based on only a partially known oeuvre, with many buildings destroyed, altered

Figure 8

Figure 8

Christ Church Steeple, Philadelphia, 1752. From Owen Biddle, The Young Carpenter's Assistant, 1810. (CWF #84-2131)

19

or poorly illustrated, there is a discernible design pattern to Smith's work. His buildings may be grouped into three broad categories: domestic, ecclesiastical and institutional. A lack of extant examples and information prevents the inclusion of Smith's domestic buildings in the following sections.

During the decade of 1757-1767, Robert Smith built five churches: the First Presbyterian Church, Carlisle, Pa., 1757; St. Peter's Church, Philadelphia, 1759 (Fig. 9); St. Paul's Church, Philadelphia, 1760 (Fig. 10); the Third Presbyterian Church, Philadelphia, 1766 (Fig. 11); and Zion Lutheran Church, Philadelphia, 1767.10 With a few exceptions, these churches are designed in a fairly consistent form: three-bay pedimented gable ends, usually serving as a facade; gable-end Palladian window; bull's eye window in the tympanum; modillion cornice; roundheaded sash windows; giant order pilasters (chimneys are aligned with these on the long sides); five-bay sides composed of three central window bays between end door bays; and central gable-end doorways, usually with pediments. Smith's first church, the Second Presbyterian, 1794, which is preserved only in poor illustrations, was different from the others by virtue of its tower and steeple; St. Peter's Church alone had a cupola which was later replaced by a tower and steeple.

Just as Smith's ecclesiastical work falls into a form pattern, so does his institutional work: Nassau Hall (the University of New Jersey, later renamed Princeton University), New Jersey, 1753 (Fig. 12); Carpenter's Hall, Philadelphia, 1768

Figure 9

Figure 9

St. Peter's Church, Philadelphia, Robert Smith, 1759. The cupola was later replaced by a steeple designed by William Strickland. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Figure 10

Figure 10

St. Paul's Church, Philadelphia, Robert Smith, 1760. Altered in the early nineteenth century. (CWF #84-TCM-502)

Figure 11

Figure 11

Third Presbyterian Church (Old Pine Street Church), Philadelphia, Robert Smith, 1766. Altered in the nineteenth century. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Figure 12

Figure 12

Nassau Hall (the University of New Jersey, later renamed Princeton University). Robert Smith, 1753. Smith also designed the Dean's House seen on the right, ca. 1754. (Princeton University Library)

20

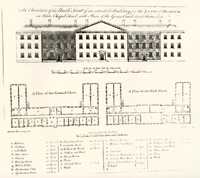

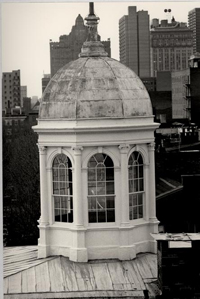

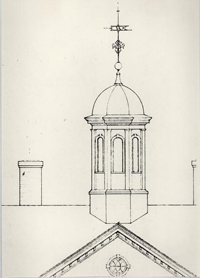

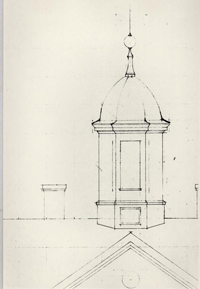

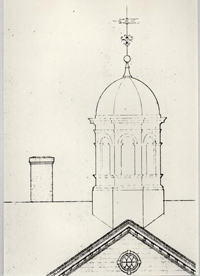

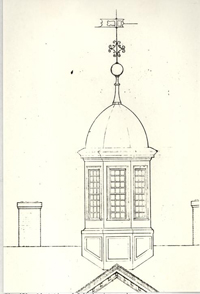

(Fig. 13); the Public Hospital, Williamsburg, 1770; and the Walnut Street Jail, Philadelphia, 1773 (Fig. 14). Because of its size and its function, Carpenters' Hall is not completely comparable, but were its wings extended, it would very much resemble the others. Typically, these large Georgian institutional buildings, a college, a hospital and a prison, were indistinguishable in exterior form. Each long side of the rectangular form (the Jail was U-shaped) was symmetrically divided by a projecting central pavilion composed of a central doorway flanked by windows. The hospital and jail had more typical three-bay pavilions, while Nassau Hall had a wider five-bay pavilion due to its excessive length. Centered in the pediment of each pavilion was a bull's eye window or in the case of the jail an elliptical window. Square-headed windows with arches, in contrast with the round-headed church windows, gave the facade a rather plain, flat appearance, which in the case of the college and jail was only enlivened by rusticated door surrounds. Also in contrast to Smith's church designs were the projecting lintels over the door arches. Georgian horizontality was maintained through a projecting watertable and a hip roof and on the hospital by a second story beltcourse. The jail, in a more fashionable design milieu, had corner pilasters without bases or capitals, which rose from the watertable. Finally, each building was graced with an octagonal cupola. In short, the large institutional building by Smith was a standard form, with certain details altered in each case. As exemplified by other

Figure 13

Figure 13

Carpenter's Hall, Philadelphia, Robert Smith, 1769. (CWF #86-372)

Figure 14

Figure 14

Walnut Street Jail, Philadelphia, Robert Smith, 1773. This is considered America's first penitentiary and was the structure which first drew Benjamin Henry Latrobe to Philadelphia when he was designing the Richmond Penitentiary.

21

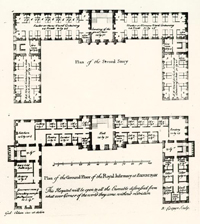

college buildings, such as the rebuilt Wren Building at William and Mary, 1705 (Fig. 15); the second Harvard Hall, 1764; Hollis Hall at Harvard, 1762; University Hall at Brown, 1770; and Dartmouth Hall, 1784, the Georgian academic form did not deviate much after the early eighteenth century. Smith's hospital and jail (prison), both new building types in America, followed this academic form. Interestingly enough, the completed form of the Pennsylvania Hospital (1755) and the Almshouse (1766) (Fig. 16), both in Philadelphia and built by Samuel Rhoads and worked on by Robert Smith, seems to be based on British hospital examples, specifically the Orphan's Hospital, Walton's Hospital and the Royal Infirmary in Edinburgh and Bethlehem Hospital in London. The common form for these hospitals was that of an 11H11 or 11U11 in plan, with a central pavilion block which rose higher than the wings and was emphasized by a domed roof or steeple and transverse gable-end pavilions. American hospitals which appeared after Pennsylvania's, namely the New York Hospital, 1773-1776 (Fig. 17-18), and the Maryland Hospital for the Insane, 1797 (Fig. 19), follow the Pennsylvania example. Smith's design for the Public Hospital, on the other hand, did not conform in exterior appearance to the obvious prototypes, but, as suggested, was rather an undifferentiated Georgian form. It more closely resembled, both in scale and form, domestic designs in Scotland and England.11

Stylistically, the Public Hospital fits comfortably within the American Georgian design of the third-quarter of the

Figure 15

Figure 15

Wren Building, College of William and Mary, 1716. (CWF #K62-JC-446)

Figure 16

Figure 16

House of Employment/Almshouse (left) and the partially completed Pennsylvania Hospital (right) drawing by Nicholes Garrison. Engraved by James Hulett, 1767. (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

Figure 17

Figure 17

The New York Hospital as it appeared in the early nineteenth century. The building was completed just in time to be occupied as a Revolutionary War barracks. It opened as a hospital in 1791. The building on the left is the 1808 Asylum for the insane. (CWF #84-TS-1836)

Figure 18

Figure 18

Plan of New York Hospital and Asylum. (CWF#84-TS-1837)

Figure 19

Figure 19

The Maryland Hospital for the Insane, Baltimore, 1797. Print by August Kollner, 1848. (Peale Museum)

22

eighteenth-century. It was, of course, characteristically provincial and outdated when compared to contemporary English works. Bootham Park Asylum in York (1772-77) (Fig. 20) and competitive designs for the new St. Luke's Hospital in London (1777), both for the insane, exhibit current neo-classical or neo-Palladian styles. In Williamsburg, the Public Hospital slipped into the colonial capital's architectural setting like an old friend. When compared to its two late colonial contemporaries, the Bruton Church tower (1769) and the Courthouse, (1770), the Public Hospital held an aesthetic edge only in its details, and even those had been simplified. Considering his ambitious architectural ideals, it is not surprising that Thomas Jefferson referred to English Georgian architecture as "the most wretched style I ever saw" and Virginia's version of it as "worse than any other part of America that I have seen."12 Jefferson obviously felt that an architectural opportunity had been lost with the Public Hospital, calling both it and the college "rude, misshapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick-kilns."13

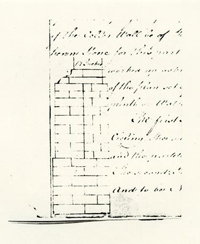

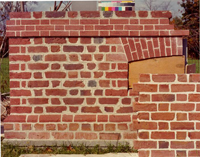

Smith's design for the Public Hospital was characteristic of his work only to a certain extent. Despite the fact that he had provided drawings and a written description, many details were locally derived. Eighteenth-century architectural drawings were generally very schematic; details such as moldings, hardware, brick bond, etc. were left to the supervising builder, and in the case of the hospital this was

Figure 20

Figure 20

Bootham Park Asylum, York, England. 1772-1777. (CWF #85-EAC-1150-15)

23

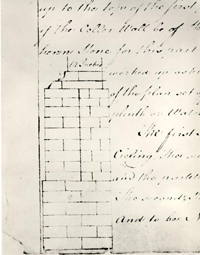

Benjamin Powell. Robert Smith's "Description" closed with a statement which acknowledges the general nature of his drawings and description: "The above hints and a careful inspection of the plan may be sufficient to perform any part of the Building."14 Powell, perhaps at the direction of the Building Committee, relied on many Smith details but rejected others. One of the few sketched details copied into the directors' minutes provides an example. In his "Description," Smith states that the "plinth or Water table . . . may be of Moulding Bricks."15 The wall section sketch depicts a two-part molded watertable that was a common Philadelphia detail (Fig. 21). Photographic and archaeological evidence suggests that Powell ignored this recommendation and substituted a one-part bevelled watertable brick common to Williamsburg and Virginia. Similarly, Powell rejected Smith's recommendation to use stone for the foundation walls, probably as stone was not abundant in the Tidewater region. A survey of eighteenth-century Williamsburg and Virginia buildings, just as a survey focused on Philadelphia, Charleston, or any other region, indicates a common pool of architectural details used by local builders. Some of the hospital's design elements can be traced to Smith's design vocabulary seen in his previous work. Due to his absence in Williamsburg, however, the building also reflected local materials and building traditions.

Economic and social factors also played a part in the design process. The disputed price of imported materials indicates a measure of economy, which is not contradicted by

Figure 21

Figure 21

Sketch of Robert Smith's proposed watertable which was copied along with his "Description" into the Hospital Directors' Minutes Book. (CWF #81-1769)

24

architectural documentation. Although concerned to a certain degree about the building's appearance, some of the trustees conscientiously valued medical over architectural treatment, as the bequest of trustee William Nelson states:

I give and bequeath to the Court of directors appointed by Act of Assembly to erect and superintend the Public Hospital for the Reception of Lunaticks &c. the sum of one hundred pounds Current Money to be by them applyed towards the farther Relief of such poor Patients as may be sent to the said Hospital, as they in their Discretion may think fit, but not to the enlargement of the Building or to any other purpose.16For all intents and purposes, the Public Hospital had been organized and was administered like voluntary hospitals in England. If Nelson's bequest can be seen as a colonial extension of the English system, a loose parallel might be drawn to the idea suggested by Adrian Forty that ornament was "generally eschewed [at hospitals] . . . on the grounds that it was a misuse of charitable funds," giving eighteenth-century English voluntary hospitals an "austere and institutional appearance."17 During the construction of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1755, Robert Smith and William Coleman were consulted about a "projection on the South side of the Ward and had given it as their Judgment that it would be no ornament and that several Physicians were of Opinion it could not be of any Advantage to the Patients, and it appearing to be likely to cost a considerable Sum, it is now agreed to drop the said proposed Projection."18 This reference suggests that Smith and Coleman considered the projection to be unornamental and therefore expendable, which seems to contradict the "austere" thesis, at least in this one instance.

CHAPTER II

NOTES

CHAPTER III

THE BUILDING COMMITTEE AND CONSTRUCTION

After the passage of the hospital act in June 1770, the trustees quickly moved to ensure its implementation. An unrecorded number of them met officially for the first court of directors' meeting at the Capitol on July 10, 1770. At this meeting five members were appointed as a building committee to "agree on a Plan for the hospital, and to advertise the building thereof; as also to receive Proposals for that Purpose of the several Undertakers, and to make a report of their Proceedings to the next Court."1 In less than a month the committee, composed of Peyton Randolph, John Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas, John Blair, Jr., and Thomas Everard, had made a decision, which was announced in the Virginia Gazette on August 2:

The Committee appointed have, in Pursuance of the above order, agreed on a Plan for the HOSPITAL, and are ready to treat with all Undertakers, who may incline to engage in the Work. It is to be a large commodious Brick Building, and to be erected in or as near the City of Williamsburg as conveniently may be.2The plan agreed upon was that by Robert Smith. Curiously, Smith's description, which survived by virtue of its being copied into the first court of directors' minutes, is dated April 9, 1770, a full three months before the public call for a plan.

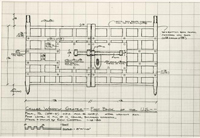

A Description of the Plan and Elevation of a Hospital for Virginia

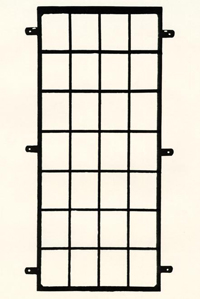

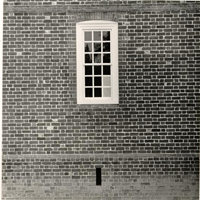

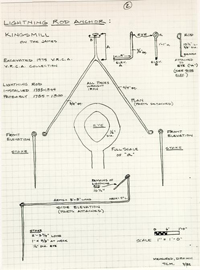

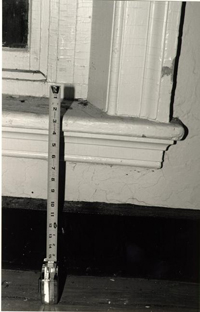

The Plan consists of a Hall for a Staircase, behind There is the Keepers apartment, and 12 other Rooms chiefly for the Reception of mad People. The Stairs begin near the front Door and land on /blank/ 28 passage in the second Story. The second Story has 12 Rooms the same Dimensions as those in the first Story, and a Room over the Keepers Apartment which may serve the Managers of the Hospital to meet or may be divided which will make two other Rooms for Patients. The Hall is designed to be open as far as the landing of the Stairs the whole hight of both Storys. The cellers, shoud be about eight feet high between the under side of the joices and the Surface of the Celler floor. And the foundation must go 12 Inches lower which will make the whole hight of the Celler Wall on which you lay the first floor 9 feet. This Wall should be 19 Inches thick either of Stone or very hard Brick and the Partition Walls shoud be 14 inches thick. The first floor is designed 3 feet above the Surface of the Ground which will require the Wall about 2 feet or a little more raised above the said Surface. This part from the ground up to the top of the first floor should be cased-with hard Brick if the Celler Wall be of Stone, unless you go to the Expence of hewn Stone for this part which will be better. After the wall is worked up as high as the first floor to the full Demensions of the plan set off about 4 Inches for the finishing of the plinth or Water table which may be of Moulding Bricks. /Sketch included here/

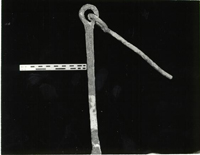

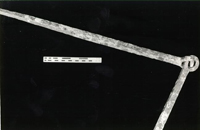

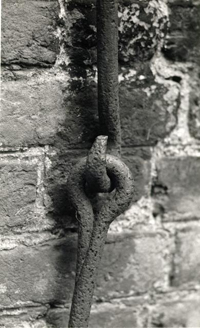

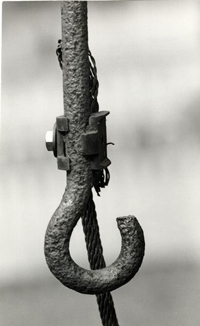

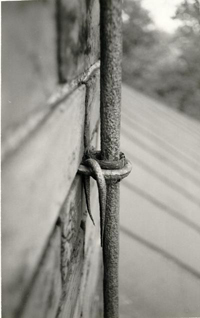

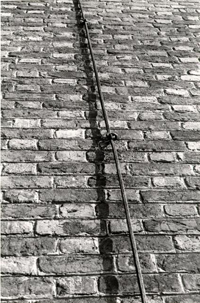

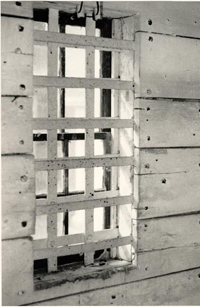

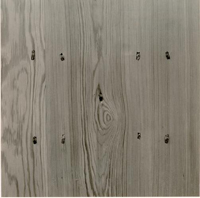

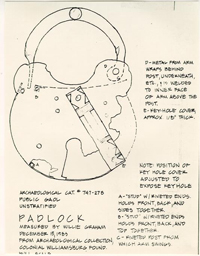

The first Story is ten feet high from floor to Ceiling. The outside Walls all round 14 Inches thick and the partitions nine Inches thick of Bricks. The second Story is designed the same thickness and to be Nine feet six Inches high. The Windows are 6 hights of Glass 10 by 8 Inches for the hight and 4 for the Width. There must be a grate of Iron to the inside of each Window which may be fixed in the following Manner. Suppose this to be the Jaums of a Window and Irons fixed ready to receive the grates when the Building is finished. /Sketch here/ I would have 2 eyes of Iron made like the rough Scratch above, which should be made of Common flat bar Iron with a hole of an Inch diameter to receive a hook which will be fixed to the Grate, the other End split and turned up or down one Inch and built in the Brick work. These two eyes should be fixed about eight Inches above the bottom of the Window and two more fixed about the same distance from the top of the window, the Grate having four hooks to fit into those eyes May be set in and a hasp fixed to the Grate at top that will fall on a Staple drive into the lintel over the Window head fix on a padlock the whole will be safe. See this rough Scratch. /Sketch here/ 29

Dimensions of the Plan feet The Keepers Apartment 22 feet In: 6 Rooms on one side 11.0 70.6 2 End Walls 14 2.4 6 Ditto 9 4.6 2 Water Tables 4 .8 Whole length of Building 100. feet in: 2 Rooms 10.9 each 21.6 1 Passage 6.2 6.2 2 Walls 14 thick 2.4 2 Ditto 9 do. 1.6 2 Water Tables 4 do .8 Whole Width of Building 32.2 N. B. The middle part projects 3 feet 6 38.2 If there shoud be occasion for Fire to warm the common Rooms, there may be Stoves fixed in the Partition between two Rooms with the Mouth open to the Passage, by which means they make fires and the mad People cannot come at them. They should be fixed about two foot above the floor for fear of the Patients falling against the Stoves. See to the left hand on the Plan the place of two Stoves.

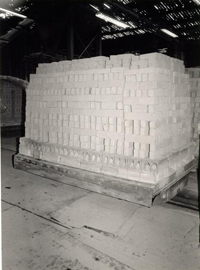

This Building will require about Two hundred thousand Bricks each Brick about 8 ¾ Long 2 3/8 Thick and 4 ½ Broad about 13 of such Bricks with Mortar will make one foot Superficial of a Nine Inch Wall or 19 ? of such to a fourteen Inch Wall. The Bricklayers must order it so that the Chimneys come out in the Roof at Equal distance from the middle otherwise they will have a very ill Effect. This may be easily done.

About 40 Thousand feet of Scantling will be wanted Superficial, which we reckon at one Inch 12 such feet makes one foot Cubical Measure.

16 Thousand feet of plank for Doors and floors about 1 1/2 Inch thick 2 Thousand feet of plank very good for Sashes &c.

5 Thousand of Inch Boards for Cornice to the Eves and other finishing besides Boarding the Roof.

The above hints and a careful inspection of the 30 plan may be sufficient to perform any part of the Building.

Philadelphia April 9, 1770

Robt. Smith

3

It would be interesting to know what information or instructions Smith's Williamsburg connection gave him. Had a prototype been suggested or was Smith expected to provide an appropriate design? The fact that the description was copied into the minutes without qualification indicates that the committee accepted the design without change. No evidence has ever placed Smith in Williamsburg, which might explain his recommendation of stone foundation walls. Unfamiliar with the region and its building practices, Smith did not know that Tidewater Virginia is virtually without native building stone. Not surprisingly, then, portions of Smith's specifications were simplified and adapted to local custom.

In September 1770, the building committee publicly announced that it would select a contractor on the 15th of the next month. In the intervening time, the committee left the "Plan and Terms" for the building with Jacob Bruce, clerk to the court, for the "Inspection of the Workmen."4 No record of the October meeting survives, but, according to the building contract which was not signed until January 1771, local builder Benjamin Powell had successfully bid the job.

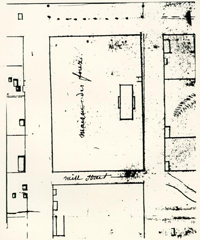

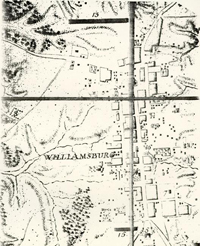

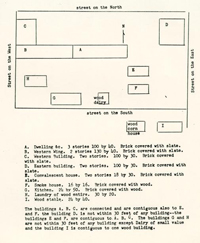

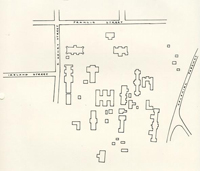

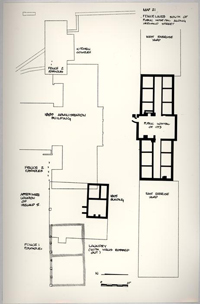

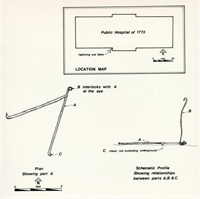

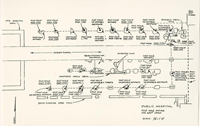

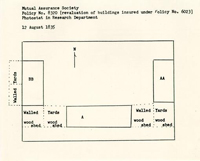

Finding a builder had not occupied all of the committee's time, however, Efforts had been underway during the fall to select a suitable site for the building. The legislative act had called for a site not larger than four acres and "the 31 most healthy in situation that can be procured, and as convenient as may be to the city of Williamsburg."5 The directors reached an agreement in November and paid Thomas Walker £112 on December 1 for eight lots in the block bounded by Francis, Henry, Ireland and Nassau Streets (Fig. 22). A deed for the same was recorded nine days later.

Before about 1760, these lots were not available for development. Their selection as building sites was only possible after the seventeenth-century house on the block burned. The house, believed to have been built by Thomas Jones, was one of the few surviving seventeenth-century dwellings in Williamsburg. It may have been the house occupied by Governor Francis Nicholson after the State House in Jamestown burned in 1698 and the capital moved to Williamsburg.6

The chosen site in the southwest section of town was essentially on the boundary of the dense half-acre lots in the center of town and the open tracts that spread out from it. (Fig. 23). The four-acre tract bought for the hospital was in fact part of a pattern of larger open town lots that developed on the south side of Francis Street, contrasting with the smaller, more typical lots on the north side of the street.7 The William Byrd III property to the west contained a house placed near the street with outbuildings and gardens fenced within its ample four-acre expanse. Similarly, to the east was the four-acre Custis tract, which contained an enclosed group of outbuildings, gardens, and pasturage.8 In conformance with the adjacent tracts, the

Figure 22

Figure 22

Detail from the Frenchman's Map, 1782, indicating a perimeter fence around the entire grounds. (CWF #N3434)

Figure 23

Figure 23

Public Hospital site and environs in 1773. (CWF #84-TS-2114)

32

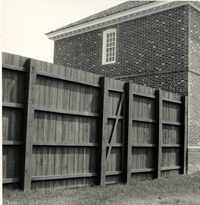

directors ordered the entire hospital grounds to be enclosed by a fence almost a year before completion of the building in 1773.9 This enclosure can be seen especially well on the town maps drawn during the Revolutionary War era (Figs. 24-25). The major departure from the treatment of neighboring sites was the hospital's placement on the rear of the lot, rather than near the street. This siting, for which no documented reasons exist, later became a major determining factor in the pattern of the hospital's nineteenth-century growth.

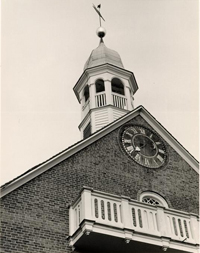

Benjamin Powell was a logical choice as the undertaker for the hospital construction. The Public Hospital, along with a number of projects, broke the hiatus in public building which had existed in Williamsburg since the completion of the Palace addition and Public Records Office of the early 1750s. Powell seemingly took the lion's share, if not all, of the new work in the 1760s and 1770s, due either to his experience and ability or, perhaps, to his social standing. He built the addition to the Public Gaol, the tower and steeple of Bruton Church in 1769, and made various repairs at the Capitol and private houses.

As a prominent man in town, Powell held a number of public offices. He owned a number of houses and lots, including his own house near the Capitol and an 1012 acre plantation in nearby York County. Although Powell is most remembered as an undertaker or contractor, he is variously described as a wheelwright, carpenter, and blacksmith. He directed a very successful business, engaging many laborers, craftsmen, and

Figure 24

Figure 24

Simcoe Map, ca. 1781, indicating a perimeter fence around the Public Hospital (number 2) with a gate on axis with the front door. (CWF #68-2329)

Figure 25

Figure 25

Detail of map, 1781 showing the Public Hospital (number 7) with its perimeter fence. (CWF #69-1512)

33

slaves, including his own. He is also known to have trained young and orphaned apprentices in the "art and mystery of a Carpenter or Joiner."10

The hospital directors later stated that "several Months elapsed before they could engage with a proper Person agreeable to their Wishes … ."11 Did Powell not bid on the job in October, 1770? If he didn't, why? Possibly Powell was engaged in other work and declined to get involved until January, conceivably upon the urging of several hospital directors. If this hypothetical explanation is the case, Powell might have been involved with the Courthouse on Market Square. All accounts pertaining to the construction of the Courthouse have been lost or destroyed, leaving part of its history to speculation. In any event, the following contract was made with Powell to complete the hospital within two years for £1,070:

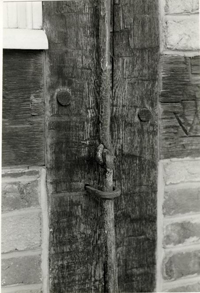

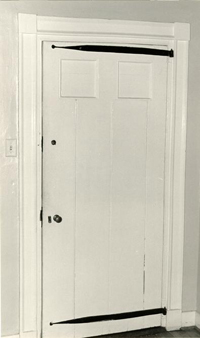

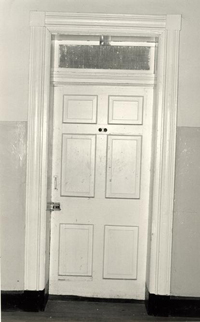

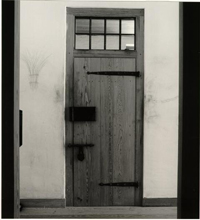

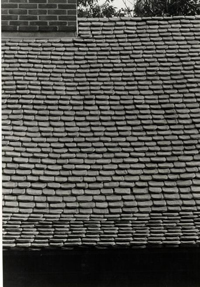

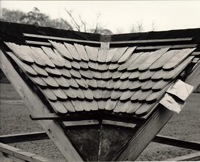

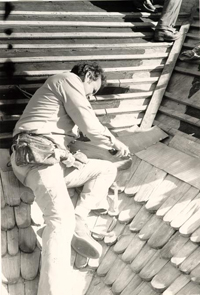

Articles of Agreement indented made and concluded this the eighteenth day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand seven hundred and seventy one Between Benjamin Powell of the City of Williamsburg carpenter of the one part and the Court of Directors of the Hospital for the Reception of Ideots Lunatics and persons of insane and disordered Minds of the other part Witnesseth that the said Benjamin Powell for and in consideration of the sum of Money herein after mentioned doth covenant and agree with the said Court of directors that he will erect a large brick Building for an Hospital for the Reception of Ideots Lunatics and persons of Insane and disordered. Minds on the Lots lately purchased by the said Court of Directors of Thomas Walker agreable to the plan and explanation thereof hereto annexed The whole Wall of hard well burnt Bricks and laid with good Mortar the North front of the middle Building to have a neat Pediment of the South East and West ends to be hipped to have a neat Mundelian Cornice round the whole the Roof to be covered with plank and good Cypress Shingles the Frame and Scantling to be of good Oak or poplar and of proper 34 Sizes for such a Building the Floors to be laid with good Plank well seasoned one and a half inch thick and free from Sap the outward Doors and those to the Middle Rooms to be paneled and the others strong batten Doors and the said Benjamin Powell doth agree to furnish all the materials for the said Building except the Grates and such other things as are usually imported from England and that he will finish and compleat the whole in a neat strong and workman like manner agreable to the plan and explanation thereof aforesaid within two years from the date hereof In Consideration whereof the said Court of Directors do agree to pay the said Benjamin Powell one thousand and seventhy pounds in the following manner that is to say two hundred and fifty pounds part thereof in hand and the Residue at such Times and in such proportions as the said Court of Directors shall think fit to direct having regard to the progress of the work.12

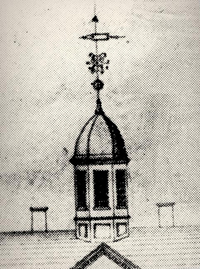

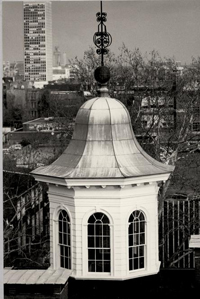

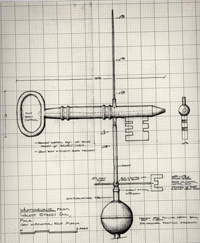

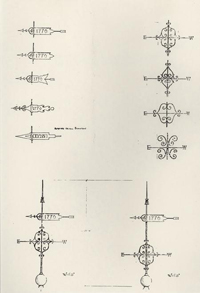

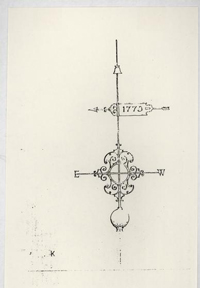

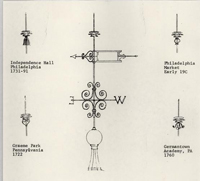

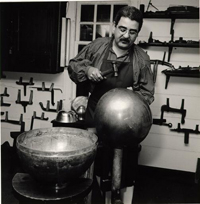

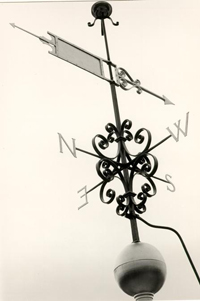

Presumably, a number of sawyers began the task of felling oak, poplar, and pine trees in the winter of 1771. Through the spring and summer, hewn and cut logs were added to the increasing inventory of finished timbers which were numbered and set aside.13 At the same time, frames for windows and doors would have been started, with the actual sash and doors following. Meanwhile, to certain directors fell the responsibility of procuring materials "as are usually imported from England." Three days following Powell's commitment to the project William Nelson wrote to London merchant Robert Cary for an unspecified number of "Articles,"14 which amounted to the sizeable sum of £188.13..9.15 The only documented item from this order is the weather vane, recorded by virtue of a price dispute, as these letters from Nelson to Cary testify:

[Sept. 5, 1771]

35…the Invoice of the Cross, Vane & ca amounting to 27.14..-which is received & I credit you for it in Account; but the Builder says that it is most extravagantly dear, & that he hath had one made here nearly as Good for £12 our Currency, tho' the spindle is not turned, as this is; and therefore, if no Abatement is made, I shall think they take a very unfair Advantage of Charging what they please for their goods.

16

[Nov. 21, 1771]

I hope you will try to get some Allowance for the Excessive Charge of the Weather Cock, which I complain'd of before or I shall think I am hardly dealt by.17

[Feb. 21, 1772]

I observe the Reasons, which Mr. Millington gives for the high Price of the Vane & Ca. which I suppose I must be satisfied with tho not convinced that it was not too Dear.18

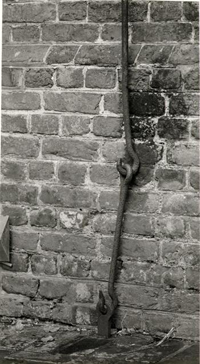

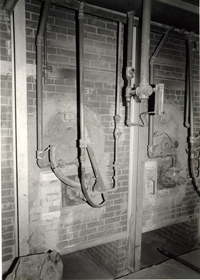

Director Robert Carter was responsible for ordering the window and transom grates specified in Smith's "Description." Carter's charge was not due to circumstance; he was a partner in the Baltimore Iron Works from which he ordered the grates in April 1771:

. . . I send 2 patterns of wood to shew the sizes of grates wanted for an hospital now building here for the reception of Lunaticks 24 of the larger size are wanted 24 of the other size are wanted, both sizes to be made of wrought iron and 48 hoocks--the directors who superintend the building expect that you signify to me the price you ask for the same, also the time you require to finish the said work-- . . . .19The grates, which Smith must have modelled on a Philadelphia example, were shipped from Baltimore on October 2, 1771.20

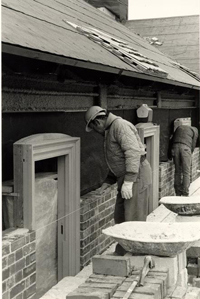

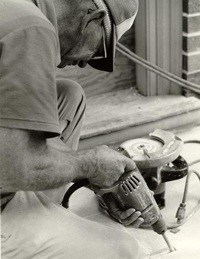

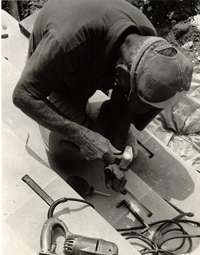

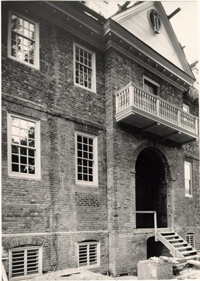

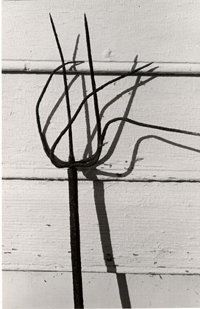

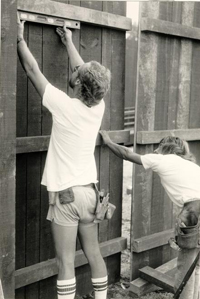

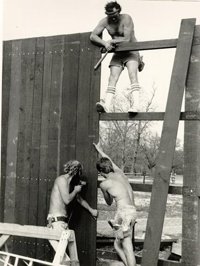

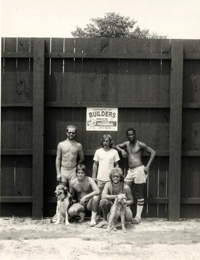

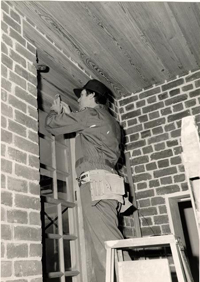

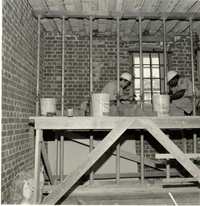

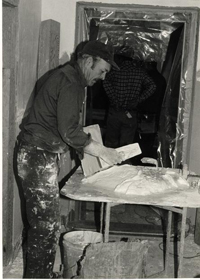

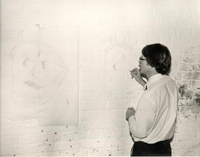

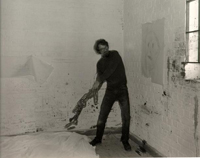

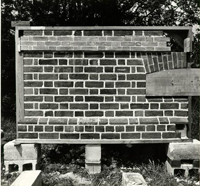

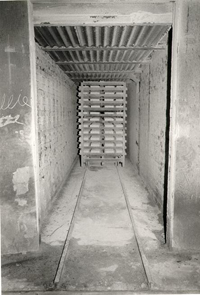

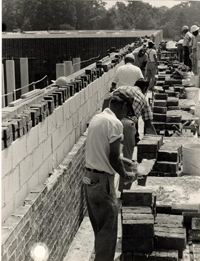

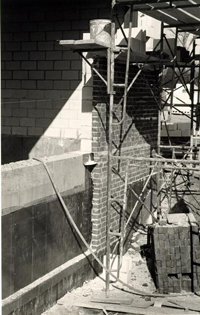

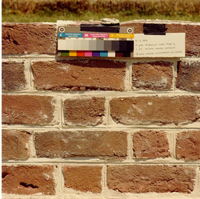

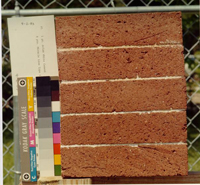

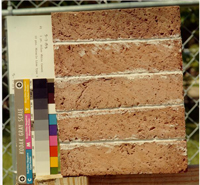

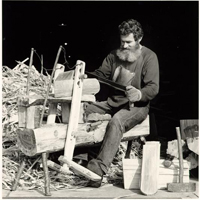

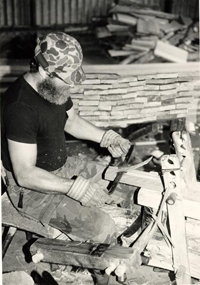

Having coordinated the acquisition of several crucial materials by the fall of 1771, Powell began putting them all 36 together (Fig. 26). Brick mason Samuel Spurr had been chosen by Powell earlier in the year. Spurr had previously worked for Powell at the jail and probably at the church as well.21 While the wood framing members were prepared and the grates were wrought, Spurr was undoubtedly making bricks and lime for the hospital, as indicated by his advertisement in the Virginia Gazette on October 2, 1771:

The frames for doors and windows, as well as the grates for the same, had to be on hand before Spurr began his work, even though the late starting date meant that not much would get done before cold weather halted the work.Williamsburg, October 2, 1771.

THE Subscriber will give good Wages, and Accomodations, to two or three Journeymen BRICKLAYERS, for the remaining Part of the Season, to work upon the Hospital building in this City. Plenty of Bricks and Lime is ready, so that they were will be no Delay.

SAMUEL SPURR22

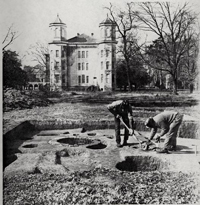

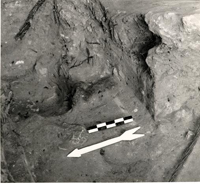

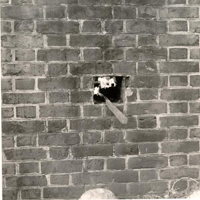

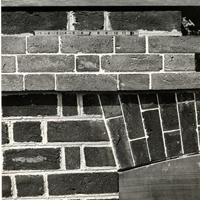

On December 16, 1771, soon after Spurr started the foundations, the directors ordered that the walls be increased by one half brick from the width specified by Robert Smith. Either the builder or the mason had recommended thicker walls. Archaeology confirmed this increase of about 4" for the outer foundation walls and the central north-south pavilion walls.23 On the average, Spurr's bricks were found to be slightly larger than the specified size.24

By February 1772, the directors realized that there would be a building cost overrun. Just to finish the building

Figure 26

Figure 26

This illustration from Diderot depicts the type of activity associated with the Hospital's construction. (CWF #85-235)

37

they would have to spend thirty percent more than their appropriated E1200. In addition, they pointed out to the burgesses that other necessary expenses were apparent, including the enclosure of a "Garden and Yards for Patients to walk and take in Air in" and salaries for a keeper and matron.25 The burgesses responded with an additional allocation of £800 in April of that year, the same month in which the stone steps ordered by Director Robert Carter Nicholas arrived from England.

Work proceeded during the spring, summer, and fall of 1772, but the building was not yet finished by the scheduled completion date of January, 1773. Eight months later, however, the directors met, examined the building, found it finished "according to Agreement," and turned its operation over to James Galt, the first "Keeper of the Hospital."26 Two days later an advertisement appeared in the Virginia Gazette informing the public of the hospital's completion and opening date, October 12, 1773.27

CHAPTER III

NOTES

CHAPTER IV

PLAN, FUNCTION AND USE

The Public Hospital's exterior appearance was culturally determined its institutional and public nature. Its familiar style associated it with a certain class of society, whose values and ideas were implicit in establishment and purpose of the institution. Yet, as we have seen, the exterior form was undifferentiated as to function. Robert Smith designed a college and a prison which did not look all that different from the Public Hospital. If the architect used such an ideal exterior form, did he also design an ideal interior plan to facilitate the hospital's intended use and purpose? To answer this we must look to the founders or clients of the building, who established its social role and setting; to the traditional or existing architectural prototypes available, which may or may not have reflected a similar need in different regions or cultures; and to the users of the building, who eventually determine the success or failure of the interior spatial arrangement.

Even though it was established as a publicly funded institution and then continued under the jurisdiction of the state after the Revolution, the Public Hospital was, by and large, operated along the lines of the private voluntary hospital system in England. Medieval hospitals in Europe had developed principally by benefactors and monastic nursing orders who hoped for spiritual salvation through charitable acts.1 These open

42

plan hospitals were consequently arranged around religious services, specifically an altar. By the eighteenth century, the religious hospital had been replaced by a secular version established, funded and privately administered by mid-level gentry. According to Adrian Forty, cure for the indigent and "poor" represented only one part of these hospitals' function. Moral reform was the other goal. The private subscribers administered the hospital, appointed the doctors, and controlled admissions. Along with the prestige, these managers used the hospital as a device to reform and control the cost of the relief system for the poor. Concern for both the "deserving" and the "undeserving" poor led to the creation of an institutional setting as a means of moral reform. In America, the hospital system developed in a dual manner. Publicly controlled almshouse hospitals served the pauper, the criminal, the insane, the orphan, foundlings, and all those who could not afford a physician's house call.2 Voluntary hospitals of a better nature also developed, the Pennsylvania and New York hospitals being early and prime examples. These institutions were modelled on the subscriber-run voluntary hospitals in Britain, for example, the London Hospital of 1752 (Fig. 27). They differed from almshouse hospitals by having a more competent staff, selected patients, medical students, and a lay board of administrators. Physicians who served in voluntary hospitals did so primarily as a social and honorary obligation. The arrangement of space in

Figure 27

Figure 27

The London Hospital, 1752. (CWF #84-TS-1839)

43

such a hospital was consequently organized by authority and social function.

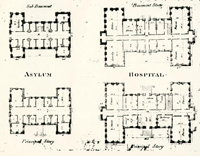

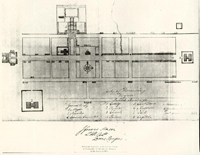

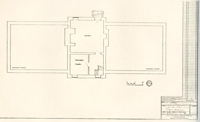

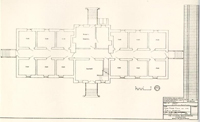

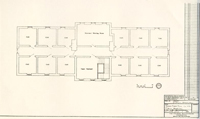

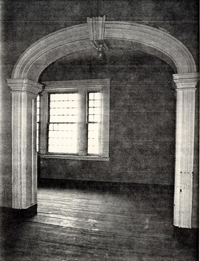

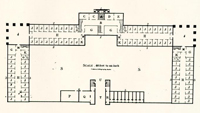

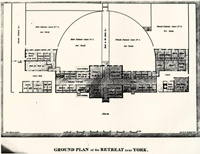

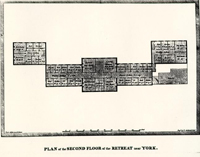

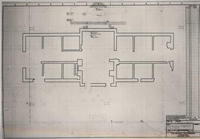

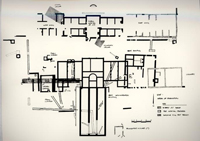

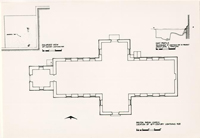

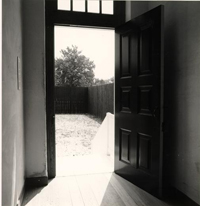

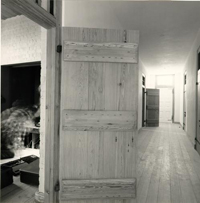

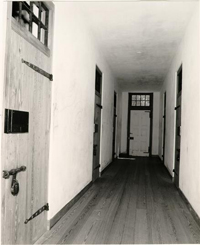

Robert Smith arranged the Public Hospital interior in response to the four groups of people who would interact within the building. This approach resulted in the placement of public and administrative spaces in the most prominent positions, very much like both English and Scottish examples and also Smith's other institutional works. Upon entering the Public Hospital through its north doors one encountered an entrance and stair hall that occupied the north half of the central pavilion (Figs. 28-29-30). An open staircase on the east wall of this hall led to the second floor and the most significant room in the building: the directors' meeting room. In this room the directors administered the hospital and interviewed patients for admission or discharge. There was no physician's room, indicating his relatively adjunct position at this time. Next in terms of importance were the keeper's quarters separated from the entrance hall by a lateral passage in the central pavilion. The keeper thus lived in the building and oversaw the daily supervision of the patients and staff. From his central location the keeper could easily reach the cells on either floor, the hail, the directors' room, the cellar, and the exterior through a south door. The staff, consisting of a matron and several attendants (both hired and slave), had use of the central pavilion cellar, which contained a kitchen, laundry, and storeroom, with access through an exterior bulkhead entrance on

Figure 28

Figure 28

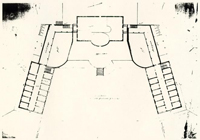

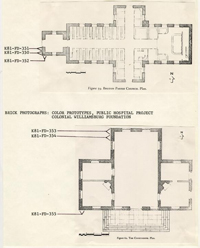

Public Hospital. Reconstructed cellar plan ca. 1773. (JFW, TCM)

Figure 29

Figure 29

Public Hospital. Reconstructed first floor ca. 1773. (JFW, TCM)

Figure 30

Figure 30

Public Hospital. Reconstructed second floor plan ca. 1773. (JFW, TCM)

44

the south or by interior stairs. The most inaccessible spaces, the cells of the patients, were reached through closed central passages in the wings of both floors. Patients took food in their cells and went out only for exercise in the flanking exercise yards reached by east and west end doors. Physically, and in principal, this arrangement is not very different from Robert Smith's plan for Nassau Hall, where the most socially important spaces were grouped in the central pavilion with lesser functions in the wings (Fig. 31). Smith's plan for the Walnut Street Jail also had a similarly organized plan of important administrative spaces in the most publicly accessible parts of the building, with the work and storage spaces and the prisoners' cells in privately controlled areas (Fig. 32). Thus, we find that a system of interior arrangement was at work, with certain basic principles applied in each case. Given this premise of a basic social governing system, Smith could very well have designed the Public Hospital's interior based on the requirements combined with the preferred overall form of the building. There is, however, good reason to think that Smith turned to a specific and appropriate prototype when designing the hospital's "ideal" interior.

On December 7, 1754, Samuel Rhoads presented the managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital with a plan and elevation for the new building. Two weeks later Rhoads appeared again and "laid before the Managers the plan of the several floors and Elevations of the Edinburgh Infirmary some parts of which they

Figure 31

Figure 31

Nassau Hall (College of New Jersey: Princeton). Plan by Paul Norton (?) (Princeton University Library)

Figure 32

Figure 32

Walnut Street Jail, Robert Smith 1773-1777. (Library Company of Philadelphia)

45

have taken into their further considerations" (Figs. 33).3 While this prototype was not copied in all respects for the first general hospital in America, the individual basement cells for the insane, arranged on either side of a central corridor, most certainly were taken from the Edinburgh example (Fig. 34).4 Robert Smith probably saw the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary firsthand, as discussed earlier, but more importantly, he knew of its adaptation for the Philadelphia building, which would have been a much more vivid prototype.5

What then were the determining factors which made this interior arrangement an ideal plan for the Public Hospital? The clues can be found in society's reasons for needing the institution. To reiterate, in their legislation the founders of the hospital expressed two concerns: fear and cure. Until the nineteenth century, medical treatment had little effect on the patients' physical environment. on the other hand, security played a great role in the purpose, function and design of the hospital. In fact, accommodations for the insane were more closely allied with those for the criminal than those for the sick. Before specialized settings were created, the insane were commonly placed in jails where the use of individual cells was typical, especially in large institutions. European and American examples were similar except perhaps for scale (Figs. 35 & 36). The intention was to remove a threat to society and, once inside an institution, to separate and secure the patients from each other and from their keepers. This was achieved primarily

Figure 33

Figure 33

Edinburgh Infirmary, ground and fourth floor plans. (William Adam, Vitruvius Scoticus) (CWF #84-2130)

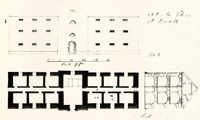

Figure 34

Figure 34

A conjectural east wing cellar plan showing the hyphen where the cells for the insane were located. (TCM)

Figure 35

Figure 35

Northhampton County Jail, Eastville, Virginia, eighteenth century. (WF #83-1224)

Figure 36

Figure 36

Fisherton Anger County Gaol, cell block, E. Lush, 1791. The type of English county jail that might have typically held the mentally ill. Note the remarkable similarity to the Public Hospital Plan. (CWF #84-TS-1835)

46

through physical restraints: individual cells, barred windows, barred transoms, locked and bolted doors, high fences and walls, and one or a combination of individual leg and wrist fetters, straight jackets, or special restraining beds and chairs. Again, even if Smith had known of Scottish settings for the insane, he would have been much more familiar with the Pennsylvania Hospital. "Mechanisms" of security were used routinely at the Pennsylvania Hospital, including fetters, straight jackets, heavily secured doors, high exercise yard fences, and barred windows; The latter were documented in the hospital minutes for 1758: "It appearing by the Reports that several of the Lunaticks have made their Escape owing to the iron bars of the Cells being too slender. Tis agreed that the Monthly Committee employ the same Smith [i.e. blacksmith] who made them to make them stronger & more secure."6 When it came to designing the Public Hospital, Robert Smith's explicit description and sketches of window and transom grates expressed at least one purpose and intention of its managers.

EARLY USE AND FUNCTION

The early use and function of the hospital can best be described as trial and adaptation. With a small patient population in its earliest years of operation, the keeper, physicians and directors slowly learned the business of a "Madhouse." Much of this business involved ordinary daily activities such as might be found on a plantation with a similar number of people to feed and clothe, gardens to tend, and structures to maintain. Outbuildings mentioned in 1744 were a well, a smokehouse, and a house for straw (necessary for patients' bedding). Other outbuildings were added to the complex at a steady rate. Garden implements seem to dominate the accounts of purchased goods, along with domestic items such as candles, soap, blankets, mops, brooms, buckets, tin and earthen cans and pans, wooden trays, chamberpots, etc. Provision of clothing (breeches, jackets, gowns and shoes) appears to have been adequate, and the extensive accounts of purchased food items indicate a surprisingly complete diet.7

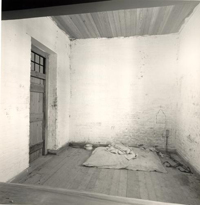

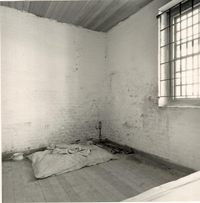

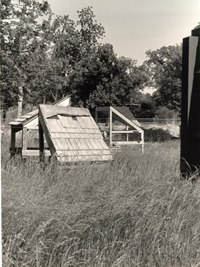

In the earliest years, local builders, carpenters, and masons were called upon to replaster walls and fix broken windows (planked up or filled with "dead lights"); to repair the cellar kitchen floor, chimney or hearth and to build an oven; to whitewash the interior almost annually; and frequently to construct coffins. Other accounts reflect the specialized function of the building, which necessitated certain additions or alterations. Before the building was finished the directors 48 realized that enclosed "airing" yards would be required for the patients, so in their request for additional funds in 1772 they mentioned that "it will be necessary to inclose a Garden and Yards for Patients to talk and take the Air in."8 Although there is no mention of yards, fences or walls in either Smith's "Description" or in Powell's contract, an "airing" yard was an indispensable appendage of any facility of incarceration. European almshouses, prisons, and hospitals for the insane all had attached yards enclosed by high fences or walls. Typically, these were adjacent to the building, segregated, and usually barren of amenities (Fig. 37). The fence erected by Benjamin Powell in the fall of 1773 most likely served the dual purpose of enclosing the hospital lots and providing an area for air and exercise. Due to the small number of patients during the earliest years and the advent of the war, it was not until about 1790 that a sufficient number of patients justified the addition of 80' x 30' fenced exercise yards flanking the hospital at each end. These paled fences, which were replaced in 1799 by ten foot high brick walls, enclosed yards which until 1800 were devoid of structures or shelters, resembling the description of an English "airing" yard "where no tree nor shrub nor flower nor blade of grass grew...;"9 The two yards made possible the segregation of male and female inmates. In large hospitals for the insane, such as Bethlehem Hospital, and in prisons or almshouses, men and women were further classified by degree of illness into separate yards.10

Figure 37

Figure 37

the first Bethlehem Hospital, 1676, shown here, originally had one exercise yard at each end of the building enclosed by 14' brick walls. When the new Bethlehem Hospital was constructed in 1815 it featured numerous exercise yards for various classes of patients. (Bethlehem Hospital Archives) (CWF #86-365)

The hospital stayed in operation during the Revolutionary War, but only barely. Petitions to the governor and the House of Delegates throughout the war years consistently refer to a shortage of operating funds, supplies, and salaries for the keeper and physicians. These problems forced the hospital to close sometime around 1781, but by 1786 a new General Assembly act of incorporation had put it back in business.

Years of neglect necessitated extensive repairs after this hiatus. But, more importantly, a level of full operation in the late 1780s led to alterations that indicated the interaction of patients and staff in the building. One of the obvious oversights in Robert Smith's interior plan was the reliance on one stairway to the second floor. By its placement, this one staircase served all of the user groups: the directors, the staff, and the patients. For patients to be taken from the second floor out to the exercise yards, they had to walk through the entrance hall, the most public space. It was apparently decided that this created a circulation problem, and staircases were ordered built at each end of the passages in 1790, providing a more private means of circulation for both staff and patients.11

Other alterations at about this same time include the installation of a partition dividing the keeper's quarters into two rooms and the addition of isolation cells in the cellar for patients with the "raving phrensy."12 This last alteration foreshadowed the classification system that became a major aspect 50 of the Moral Management era in the nineteenth century. In effect, there was some acknowledgement at this time that separating patients by degree of disorder would be beneficial to the patients, especially those with less severe problems. The specific solution, however, cannot be seen as humanitarian.

The new state government's commitment to reopen and reestablish the Public Hospital in 1786 was a crucial one. Continuance of the institution after the war meant that it had become the first state-controlled hospital for the insane in America. Equally important, it had been given new life at a time when the town needed an economic anchor. Onley Winsor, who visited Williamsburg just after the repairs in 1786, left a graphic picture of the hospital's physical relationship to the town at that time.

Here is a large handsome brick Mad House (for Lunaticks &c)--all the public buildings except the Mad House, are in a decaying situation, as most of the Private buildings, business haveing almost entirely left this place since the removal of the Government.13

By June 1799 the directors announced to the public that the hospital was full and would not accept new patients. With the new century the hospital steadily expanded in both its number of patients and number of buildings. The hospital was also entering the age of the American psychiatric profession, an age during which hospital architecture and medical treatment became much more closely allied.

CHAPTER IV

NOTES

CHAPTER V

NINETEENTH-CENTURY GROWTH

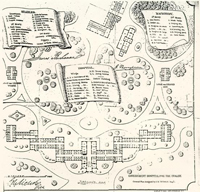

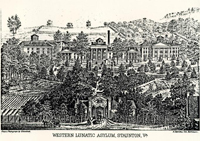

If the eighteenth-century history of the Public Hospital is characterized by a somewhat isolated and idiosyncratic effort at treatment, its nineteenth-century history reflects the "age of the asylum" and the increasingly important role of the psychiatric profession in the appearance and function of hospitals. But, as Norman Dain has noted, the administration of Dr. Alexander D. Galt in the hospital's second major period, 1800-1841, did not take advantage of the new theories of Moral Management which had developed in England and France around the turn of the century.1 From Pinel and Tuke, in France and England respectively, came a revolutionary theory regarding the treatment of the insane that stressed non-restraint, kindness, and provision of un-jail-like environment for the patients (Figs. 38 & 39). The hospital in Williamsburg evolved in relative isolation from these new theories of mental health treatment until just before Dr. John M. Galt II became superintendent in 1841.

By 1804 outbuildings had accumulated to the south of the hospital, giving the site a full range of subsidiary domestic structures: well, smokehouse, house for straw, privies, stable, dairy, corn crib, sheds, and bath house.2 A small one-and-a-half story house, which came with the property just south of Ireland Street, eventually served as the matron's residence (Fig. 40).

Figure 38

Figure 38

Dr. Philippe Pinel, one of the pioneers of moral management theories. (CWF #81-FD-4376)

Figure 39

Figure 39

Samuel Tuke, founder of the Retreat in York and the father of Moral Management practices. (CWF #86-373)

Figure 40

Figure 40

The Galt Cottage. (CWF #66-791)

By this time, a wooden fence enclosed the entire hospital site; gardens, with their own fences, occupied part of the enclosed grounds; ten-foot-high brick walls had replaced the exercise yard fences flanking the hospital; and the exercise yards contained "covered walks" for the patients. Because the hospital had continued to run at capacity since 1799, an additional building for "the accommodation of the patients, the keeper and matron" was constructed in 1804-1805 as a detached structure slightly south and east of the main building. The new building was later referred to as the convalescent or "bettering house." An 1821 insurance policy described this building as "brick with a wooden roof, two stories high, and 32' x 18'."3

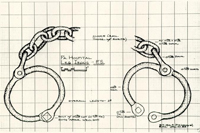

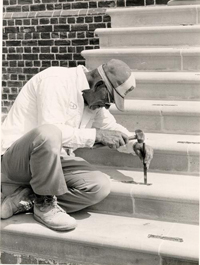

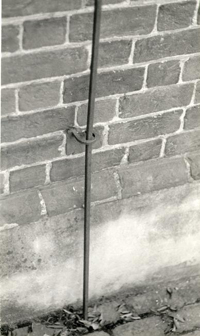

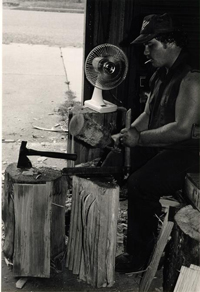

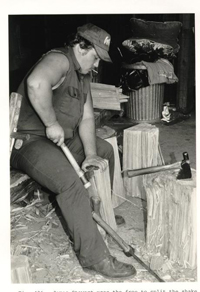

Minutes of the Board of Directors are missing for the period 1801-1822, but repair accounts survive and indicate a wide range of maintenance work. Typifying this maintenance work are three accounts by a bricklayer, a carpenter, and a blacksmith. Bricklayer James Semple's 1805 account shows that he repaired ovens, chimney backs, doors, and windows; underpinned a smokehouse, stable and necessary; built a well; laid a brick cellar floor; did plaster work; and whitewashed 27 rooms. In 1811 carpenter John Bowden replaced or installed window glass, locks, doors and door sills, floors, steps, washboards, and cellar caps. He also made coffins. Blacksmith James Hay's account from 1815 documents a wide range of work: repairing keys, locks, carts, wheelbarrows, hasps, tools, and a ducking chair. There are also many references to Hay altering or 55 repairing leg irons and chains--typical eighteenth- and early-nineteenth century leg irons required a blacksmith to put them on and take them off (Fig. 41).4

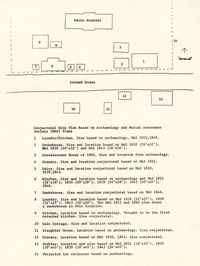

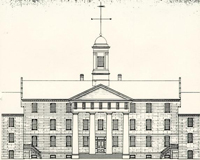

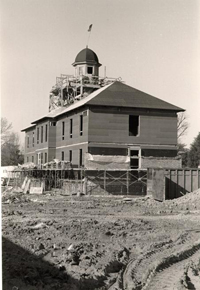

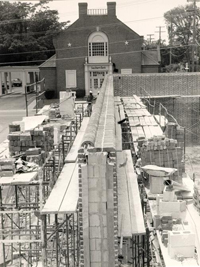

The location of outbuildings to the south of the hospital on the four-acre site dictated the placement of any new buildings for patients to the north or front of the original building (Fig. 42). The first of these additions was a 40' x 33' two-story brick building containing twelve cells, constructed in 1820-22 just to the northeast of the original building. This $4,000 building, which was roughly equal in both size and accommodation to one wing of the original building, was duplicated with a corresponding building to the northwest in 1824-25. These flanking buildings can be seen in a drawing (believed to have been executed by keeper Dickie Galt in 1829) that shows the north elevation of the original building after the addition in 1828 of a "portico" or porch and the replacement of original window sash and sills (Fig. 43). The full range of cellar windows in the drawing is a mystery, since archaeologists determined that the cellar was originally confined to the pavilion. The dotted lines connecting the buildings represent the 10 foot-high brick walls enclosing the exercise yards. If the two buildings identified on the drawing as a kitchen and laundry are reversed, the kitchen plan corresponds to the detached kitchen documented by archaeology.5