Pamunkey Recognition

by Ben Swenson

Dave Doody

Warren Taylor, a Colonial Williamsburg interpreter and a Pamunkey, shares his tribe's history as part of the Foundation's American Indian Initiative.

Dave Doody

The Pamunkey and Mattaponi pay their annual tribute of wild game and gifts, dating back centuries, to then-Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell.

Dave Doody

Warren Taylor says he's eager to tell Pamunkey-themed stories from pre-revolutionary Virginia. "This is my people's history and I'll take any opportunity to educate others about that. My work honors the history of my people," Taylor says.

Dave Doody

In 2014, actors re-created the wedding of Pocahontas, the daughter of Powhatan, and John Rolfe.

Dave Doody

A striped jacket, which is a reproduction of 17th-century diplomacy, is on display at the Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center.

Dave Doody

Colonial Williamsburg's American Indian Initiative helps portray the complexity of cross-cultural relations.

Colonial Williamsburg

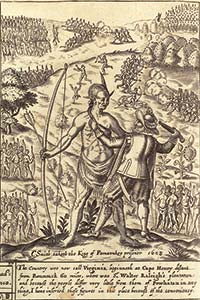

John Smith's "General History of Virginia" of 1624 includes this depiction of Smith, who was captured by Opechancanough, the tribal chief of the Powhatan Confederacy.

Pick defining events of American history. A surprising number — the settlement of Jamestown, the American Revolution, the Civil War, the Jim Crow era — were connected to the Pamunkey Indians. And yet, a nation so deeply woven into the American story has waited until the 21st century to learn whether the United States will officially acknowledge its existence.

Later this year, the Interior Department's Bureau of Indian Affairs will announce a final determination on whether or not the federal government will recognize Virginia's Pamunkey Indian Tribe. The decision will be the product of more than four decades of work, and for the Pamunkey, federal recognition, if it comes, will be a beginning as much as an end. Federal acknowledgement, as it is also called, is practical in its effects, giving tribes specific rights and access to resources that are off limits to other groups. But recognition is also a point of pride among Native American communities because it acknowledges the identity they have nurtured for much longer than the United States has existed.

The historical relationship between the U.S. government, its colonial predecessors and Indian nations has been fraught with mistrust and violence. Objects considered sacred by its people are all that's left of some tribes that once populated the North American landscape. Just west of Williamsburg, for instance, is a golf course community called Governor's Land at Two Rivers. There among the links is a plaque marking the site where the remains of 18 Indians, discovered when the property was developed, were reinterred in 1993. That forlorn grave and a historical marker on a nearby state highway are among the few remaining traces of the Paspahegh community, whose land Englishmen settled in 1607 and named Jamestown.

The Paspaheghs, part of a paramount chiefdom that included the Pamunkeys and were led by Chief Powhatan, often attacked Englishmen, whom they saw as interlopers. Englishmen returned the violence manyfold, and in one instance, abducted the Paspahegh chief's wife and children. Soldiers threw the children into the James River, then shot them to death. The Paspahegh queen they took ashore and ran through with swords.

Those sorts of depredations and tit-for-tat reprisals against indigenous communities continued for more than three centuries as Americans' manifest destiny rolled westward across the continent. More unfortunate Indian tribes faced diaspora, confinement, or worse, extinction.

Yet along that timeline, the United States established relationships with individual tribes through treaties, laws and executive actions, acknowledging that these groups were distinct nations. Unbeknownst to most Americans, the principle that federal lawmakers engage tribes as they would a separate government is enshrined in the Constitution. But after passage of a couple in the mid-20th-century laws that bolstered Native rights and privileges, some Indian tribes that had never forged such a government-to-government relationship with the United States began clamoring for that acknowledgment. One reason — federal recognition historically came with certain concessions, such as self-government.

There were financial incentives, too. The federal government's history of providing assistance to Indian tribes began in the 18th century and continued unabated through the present. The federal budget now allocates about $2.5 billion annually for Indian affairs, to cover a range of such services as education, construction and environmental grants.

As much as anything, however, the impetus that drives many Indian tribes to seek recognition is the acknowledgement of nationhood. Petitioning tribes want to hear from the United States government that they are who they claim to be.

Recognition is also a legal concession that grants privileges reserved for only those tribes. In guarded storage near the nation's capital, for instance, lie the bones of thousands of Native Americans. The remains are carefully protected by Smithsonian Institution curators, catalogued and shelved under lock and key in climate-controlled rooms.

This odd collection is a legacy of an era that lasted into the 20th century when scientists, researchers, even everyday curiosity seekers often excavated sites sacred to Native Americans and other groups both in the United States and around the world. Those investigations took items of cultural significance, funeral objects laid to rest with the deceased and even human remains. In 1893, for instance, anthropologist Gerard Fowke wrote of what he called the "most interesting site yet discovered" in Virginia during his years-long quest to study indigenous burial mounds: "... more than 200 skeletons were exhumed, with a great number and variety of associated relics."

In the latter half of the 20th century, mounting protests from Native American communities decrying the excavation of sacred sites and human remains shifted public opinion against keeping so sensitive a collection. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act required museums and agencies that receive federal funding to repatriate these items from whence they came. Tens of thousands of people and objects disturbed from their eternal rest have since been returned to tribes across the country.

An estimated 1,400 sets of Virginia Indian remains are still in the custody of federal curators because the law proscribes that they may only be given back to a modern tribe of likely descent that is recognized by the federal government.

The Pamunkey are not sure if the repatriation of the collected artifacts from historic Virginia Indians will be among their priorities after recognition. For now, according to Chief Kevin Brown, they'll take a measured approach to all the prerogatives of federal acknowledgement. But the future of any action, or inaction, will be theirs to decide; the United States will concede a federally recognized tribe's sovereignty in the matter.

In 1978, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or BIA, established criteria that, if met, would result in a tribe';s federal recognition. Policymakers, many of them Native Americans, set the bar high. Indians regard their Native identity and sovereignty with gravity, and don't want to debase their proud heritage with spurious claims. And the bureaucrats controlling the federal purse strings are likewise loath to open federal coffers to people whose Native identity is more wishful thinking than blood quantum.

To date, the United States government has recognized 566 Indian tribes.

Tribes petitioning the BIA for federal recognition must prove they're a longstanding, distinct community of Native Americans with established governing authority among members, which is no easy task. Since 1978, 17 have met this burden of proof — and 35 have failed. Tribes often navigate the process, only to be told after decades of perseverance that their petition has been declined.

There are two other methods for acquiring federal recognition — through an act of Congress or a ruling of a federal court, both of which rarely occur. Six Virginia tribes — the Rappahannock, Chickahominy, Eastern Chickahominy, Nansemond, Upper Mattaponi and Monacan — have tried unsuccessfully to secure recognition through Congress.

The Pamunkeys never doubted their identity, so in the early 1980s, they began the process of seeking federal recognition through the BIA.

Odd about the Pamunkeys' bid for recognition is that it has taken so long for the federal government to consider acknowledging so well known a tribe. The Pamunkey were among the first to greet the Europeans who explored and colonized their land, Tsenacommacah, and they were the tribe of Chief Powhatan and Pocahontas — or, as they were known to their contemporaries, Wahunsonacock and Matoaka.

The Pamunkey signed a couple of 17th-century treaties that established their reservation. Their land and that of the Mattaponi tribe 10 miles north, are the two oldest reservations in the United States. To this day, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi pay an annual tribute of wild game and handcrafted gifts to Virginia's governor at his residence. They have continued this tribute every year for as long as their reservations have existed, more than three centuries.

The Pamunkey appear early and often in the historical record. They are in the writings of John Smith and Thomas Jefferson. Virginia's archives teem with Pamunkey paperwork, as the tribe often petitioned the state government on matters ranging from their reservation to legal rights, demonstrating their knowledge and protectiveness of their identity. There are also numerous snapshots in local daily newspapers as with this from an April 1894 issue of Washington, D.C.'s The Evening Star: "Powhatan's Men Yet Live," reads the headline. "Its Last Remnant Still Exists in the Pamunkey Indians of Virginia."

The article understates the case; several existing Virginia tribes — none federally recognized — claim descent from the Powhatan chiefdom. In fact, Powhatan's men, Pamunkeys, are alive and well, and one of them can often be found in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area interpreting his tribe's rich history.

Warren Taylor shares Pamunkey history as part of Colonial Williamsburg's American Indian Initiative. Taylor and another Native American interpreter depict Pamunkey-themed scenes from pre-revolutionary Virginia, as with the story of Robert Mush, a Pamunkey who attended Williamsburg's Brafferton Indian School in 1769. "This is my people's history and I'll take any opportunity to educate others about that," says Taylor. "My work honors the history of my people, which is not known by many."

Indeed, few Americans know of the central role of the Pamunkey tribe in the early American chronicle, which is why Colonial Williamsburg sponsored several programs to shed light on that hidden history. Aside from the street characters who have been added to the interpretive platform, Colonial Williamsburg partnered with Preservation Virginia to put on "The World of Pocahontas," which included roundtables, lectures and other events to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the notable Pamunkey's wedding to Englishman John Rolfe. At an April 2014 re-enactment of the marriage ceremony, more Pamunkey Indians set foot on Jamestown Island than at any time since the 17th century.

Taylor appeared in that program as one of Pocahontas's brothers, a role he was happy to assume. "I feel like being able to portray Pamunkey people of the past is an opportunity to talk about the daily and tribal struggles that my people faced," says Taylor. And those struggles, he adds, by no means stopped when Pocahontas wed.

The Pamunkey Indian Reservation is a 1,200-acre bubble adjacent to King William County in Virginia that fills an oxbow of the Pamunkey River. This part of southeastern Virginia seems an old landscape, with bucolic, rolling countryside reminiscent of a simpler time before high-speed anything. The reservation — or "The Rez," as the Pamunkey call it — is a tidy rural community of about 80 people whose well-kept homes are situated on large lots in between expanses of corn, wheat and soybean fields. In the spring, Pamunkey men net American shad along the arcing waterfront. Their catch is brought to the tribe's fish hatchery, where milt and roe are combined to create millions of fry or newly hatched fish, which tribesmen release back into the river.

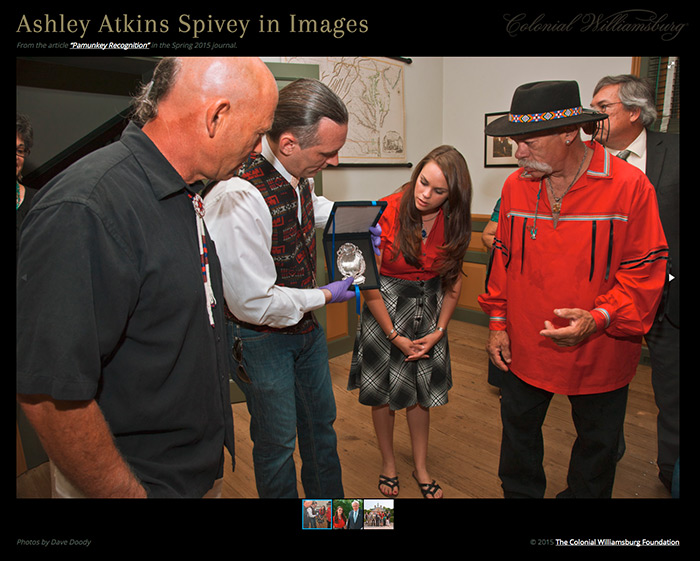

In the middle of the reservation sits the Pamunkey Indian Museum and Cultural Center, a cozy building housing artifacts found on the reservation and other displays that tell of their ancestors' 10,000-year residence here. Two reproductions of 17th-century objects of diplomacy — a frontlet, or medallion, and striped jacket — are displayed in the museum's "Treaty Room." Colonial Williamsburg tradesmen fashioned the pieces to represent originals made because of Anglo-Pamunkey treaties.

The building doubles as an administrative headquarters. In a room off to one side of the galleries, the chief and seven-member tribal council meet. For elections and sensitive issues, they circle a basket for proposals and drop in a kernel of corn to vote in favor, a pea to vote against. Behind the museum is a restored, one-room clapboard schoolhouse from the early 20th century where Pamunkey children attended school until the 1940s. Although the reservation is very much a thriving rural community, there is no mistaking its deep Native bearings.

Ashley Atkins Spivey is a member of the Pamunkey tribe and a Ph.D. candidate in anthropology at the College of William and Mary. Spivey grew up in Richmond, Va., where she now lives with her husband and son, although trips to the reservation to visit family are frequent. Aside from her personal connection to the reservation, she knows through her profession how deeply Pamunkey history is embedded in this land.

The four treaties the Pamunkey signed with the English predated the United States by more than a century. So they never really had an occasion for a face-to-face reckoning with the federal government, the kind of interaction that resulted for other, more westerly tribes in recognition. They were well integrated into the cultural landscape by the time the notion of recognition came into being.

The Pamunkey weathered several outside attempts to deny their Indian identity. In the 19th century, King William County residents twice sought to have the Pamunkey divested of their reservation because the petitioners feared racial mingling with African Americans. In the 20th century, a zealous eugenicist and white supremacist assumed the position of state registrar of vital records. He ordered Virginia Indian birth and marriage certificates read "colored" instead of "Indian."

But overwhelming evidence establishes the Pamunkeys' existence and continuity as a tribal community. Census, church and tribal records allowed genealogical researchers to flesh out a sort of massive family tree stretching back to the 18th century. Every one of the current 208 tribe members can demonstrate a generation-by-generation descent from Pamunkey Indians who were alive to witness the creation of the United States.

So the Pamunkeys' identity is in their history, government, customs and land. Their identity is also, as they have been saying all along, in their blood. They hope the Federal Register will soon say so, too.

If they are recognized, the Pamunkeys will take on a role as trailblazers. Fourteen other Virginia tribes — 10 of which, aside from the Pamunkeys, have been recognized by the state government — have expressed an interest in federal acknowledgement. More than 300 across the United States have, as well. They can all now look to the Pamunkeys' saga for guidance. Their federal recognition is, above all else, a lesson in perseverance through challenges.

"We just want people to know that the Pamunkey people still exist," says Spivey. "Many people in this country don't know that Native people exist east of the Mississippi River, much less in Virginia. We have always been here and we still are."

Colonial Williamsburg's American Indian Initiative is generously supported by donors including Douglas N. Morton and Marilyn L. Brown of Englewood, Colo.