John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Special Collections

After losing a father who hadn’t left enough money, a child, even one with a mother, could be bound in apprenticeship.

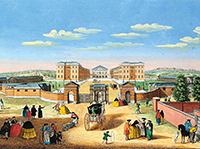

Colonial Williamsburg

The DeWitt Wallace Museum exhibit "Threads of Feeling" was put on in cooperation with the Foundling Museum in London.

Colonial Williamsburg

A hand-colored engraving, "A View of the Foundling Hospital," by Robert Sayer, ca. 1755, in the Colonial Williamsburg collection.

Library of Congress

The Orphan House in Charleston, the oldest city orphanage in the country, opened in 1795.

This Helpless Human Tide

Bastards, Abandoned Babes, and Orphans

by Michael Olmert

Among the accounts of ship arrivals, runaway slaves, and unrest in Boston, the March 4, 1775, issue of the Virginia Gazette reported that an unidentified infant had been abandoned on the road between Newcastle and Richmond, Virginia. The child was swaddled in a tiny box, along with £10 cash and a note promising a future payment to anyone who took up the child and gave it a life, though just how and to whom that money would be paid went unsaid. The entry concluded with the news that some kindly citizen had made the harmless babe his foster child.

Just below this notice, on the copy of the Gazette I consulted, someone had inserted the name “Jos. Lyle, Manchester” in thick black ink, and in an eighteenth-century hand. Was the mysterious Mr. Lyle of Manchester, Virginia, now part of Richmond, our Good Samaritan?

Here is the sum of what we know about Mr. Lyle: That there were not enough people like him in the eighteenth century. Great Britain and her colonies were struggling under a tsunami of infants with no one to care for them. These were babes who lost their mothers in childbirth, a regular outcome in an age of little or no maternal or postpartum care. Out-of-wedlock births to housemaids, servants, and slaves were another sure way of producing children untethered to those able or willing to care for them.

There were also embarrassing pregnancies among the stylish daughters of posh families who wanted the diapered evidence to disappear. A bastard child was a sure way to lose respectability and, with it, marriage prospects. Infants were also given up because their extra mouths put impossible strains on already strapped family incomes. Infanticide—especially for deformed or afflicted infants—was known. The evidence for it is hard to come by, but records show 118 women executed for infanticide in Britain between 1735 and 1829.

In the colonies, oils from the easily harvested pennyroyal plant could be infused in drinks to induce abortions. In lighter doses, spearminty pennyroyal was often used to cure minor ailments in men and horses. Similarly, the caustic irritant called savin, derived from the bushy juniper, Juniperus sabina, could also be used to abort pregnancies. In 1658, in Patuxent, Maryland, Elizabeth Robins “confessed that She had twice taken Savin; once boyled in milk and the other time Strayned through a Cloath.” She excused this, in court, by declaring she was unaware she was “with child” and took the savin to rid herself of worms. Now, however, “She Supposeth her Self to have a dead Child within her.”

The rising commonplace of prostitution in the cities—especially London—was a creature of economics. Working in the sex trade may have been the only available job for too many eighteenth-century women. Birth-control methods were undependable and expensive. The common sheep’s intestine condom was ineffective. There are reports that condoms were mainly for protecting men from disease anyway, not for preventing pregnancy in women. The result was abandoned or neglected children.

The corollary problem, somewhat more prevalent in rural areas—away from watching eyes—was girls having babies. Sometimes, the infants were fathered by the girls’ uncles and sometimes by their fathers. Partly, this was the result of overcrowding—large, or extended, families living in one room, for instance. This source of troubled births was known in cities, too. In the nineteenth century, Emmeline Pankhurst, a women’s rights advocate, knew of poor girls as young as twelve giving birth to children fathered by relatives.

With so few people to care for this helpless human tide, by the mid-nineteenth century it was said that one-third of London’s annual deaths were children. Charles Dickens saw what was happening:

The two grim nurses, Poverty and Sickness, who bring these children before you, preside over their births, rock their wretched cradles, nail down their little coffins, pile up the earth above their graves. . . . I shall ask you to turn your thoughts to these SPOILT children in the sacred names of Pity and Compassion.

In America, “these spoilt children” were never far from the institutional mind-set of the colonial courts and of the Church of England. The local parish was a font of welfare and moral support in the colonies, just as it had been in Britain. In the same way, the county courts worked to bring a measure of justice and stability to little lives blighted by the incompetence or death of parents. In both cases, it has to be said that this concern was driven by an instinct to prevent the lost children from becoming a burden to the colony and its taxpayers.

By definition, a child was legally an orphan if its father died. If the father had not left enough money or property to see the child through to adulthood, even if the mother were still alive, the parish or court could step in and settle the children in foster homes, ensure they were educated, and “bind them out” into apprenticeships.

June 15, 1761, the York County, Virginia, court ordered the wardens of Yorkhampton Parish to bind out the poor orphan Benjamin Palmer and the children of one Thomas Combs, who “neglects to Educate them,” into useful apprenticeships. In Orange County, on August 25, 1763, the court noted, “John Carrel a poor man is Runaway & neglects to maintain, Instruct & Educate his son John in the principles of Christianity.” They required St. Thomas’s parish bind out the neglected son to Robert Beadles, a shoemaker. And Frederick County, on April 6, 1773, required the churchwardens of Frederick parish to enter Solomon Wright into an apprenticeship. Solomon was the son of Isaac Wright, “who hath absconded and left a wife unable to Educate & bring up her Children.” Solomon was to be bound to Abel Walker, “who is to learn him to read Write & Cypher.”

For cases when a father bequeathed sufficient funds and property, special orphans courts saw to it that the wardens of minors’ estates could not impoverish children by liquidating their property and spending the income. In George Farquhar’s 1706 play The Recruiting Officer, the sarcastic line, “All captains have a mighty aversion to timber,” refers to the habit of army captains’ marrying rich widows and harvesting the timber on the family’s land. Although they could not sell the property, they could whittle away its assets. Standing trees were a valuable commodity in an island nation dependent on a large navy. February 12, 1736, The Recruiting Officer became the first play mounted in Charleston, South Carolina, at the Dock Street Theatre. Its “timber” line is meaningless without an understanding of the straits of orphans beset by greedy supervisors.

The economic pressure to get rid of excess or unwanted children could be so great that some people resorted to folklore. Embedded in Western culture is the idea of the changeling, a fairy infant left in the crib in place of a human baby. The belief was that you could induce the fairies to return your child if you began to slightly harm the changeling. Babies might be stuck with pins, dangled over the fire, or left in the forest for the time it took a candle to burn. Any of these were thought to strike pity in fairy hearts, in which case the human baby would be restored to its home crib.

June 25, 1752, the Virginia Gazette reported the arrest of an English mother-in-law in Malden, Essex, for using the feet of an infant to stir the coals in the hearth. After the neighbors noticed the child’s “Toes were rotted off,” the babe was taken by the parish and put in a workhouse, where it died. It is possible, in an age when the spirit world was a reality of daily life for many, that this saga echoes a sincere belief in fairy lore. It also is possible the child was deformed or sickly, or had to be sacrificed for monetary reasons. And so the family blamed the fairies to justify itself.

Another solution to the overpopulation problem and child neglect was foundling hospitals, which came to be called orphanages in the nineteenth century. The Greek and Roman world had such places. Renaissance Florence had the Ospedale degli Innocenti, “The Hospital of the Holy Innocents,” a vaulting example of civic humanism, which opened in 1445. Designed by Brunelleschi, the building had a small basin near the entrance for mothers to leave their infants. In 1660, it was replaced by a revolving-door mechanism that prevented people inside from seeing the stricken mother.

In the North American colonies, places of refuge for children were thin on the ground. Institutions tend to be expensive; the courts and the church were a cheaper alternative. There were exceptions. The Charleston Orphan House, the oldest city orphanage in America, was established in 1790 and opened its doors in 1795.

In Georgia, the charismatic preacher George Whitefield laid the first stone of his orphans home at Bethesda, near Savannah, in 1740. Preaching to crowds in Britain and America, the Calvin-istic Whitefield was constantly raising funds for this pet project. In 1754, he brought twenty-two English orphans across the Atlantic to Bethesda, his “House of Mercy.” Trouble was, Whitefield used an iron hand with the children, possibly hoping they would become small versions of his devout self. The project bogged down in controversy and debt. By 1770, when Whitefield died, Bethesda was nearly a ruin, despite supporting 180 children in its thirty fitful years.

An influence on Whitefield’s thinking about orphans was the Foundling Hospital in London, chartered by King George II in 1739 and opened in 1741. Here, the word “hospital” signifies a sense of succor and hospitality for the afflicted.

Its begetter was the wealthy shipbuilder and merchant Thomas Coram, who hoped, out of his good fortune, to leave something for “the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children.” He did that. The best and brightest Londoners flocked to aid his charity, including William Hogarth, who donated art to the project, and George Frideric Handel, who gave concerts in aid of the foundlings. In 1867, Dickens, who lived a few blocks away on Doughty Street, would co-write the play No Thoroughfare, in which a woman tries to regain a child left at the Foundling Hospital years earlier.

Its main buildings were completed between 1743 and 1752, and designed by the merchant and amateur architect Theodore Jacobsen, who built a U-shaped brick structure of two wings and a chapel, not unlike the college at Williamsburg, Virginia. The sides of the site were lined with loggias, or pavilions, Doric structures associated with outdoor teaching. Some of these are still in place, heavily restored.

Today, the chief remainder of the old hospital is a stone gate that stands unremarked next to the leafy playground now called Coram’s Fields. The curved niche in the limestone was to be seen as a safe place for desperate mothers to drop off their infants in the dark of night. Here you can just begin to imagine the shame and dread of having to abandon a child. Pointedly, the gate was not shunted off to one side, but was front and center, as if to say harmless babes were the whole point. The gateway is the only surviving part of the original hospital; the rest was demolished in 1926.

The DeWitt Wallace Museum at Colonial Williamsburg exhibited infant tokens from the Foundling Museum in London, which stands today near the site of the original hospital. The tokens were sometimes pinned to abandoned infants. They are an odd assortment—a thimble, a note, ribbons, defaced coins, brass hearts, swatches of cloth, a playing card, or a bone fish used in card games. They were meant to be telltales against the hoped-for day when the mother might return and reclaim her child. New babies were always given a new name and a number and file. Infants were sent out to wet nurses for several years. Since many a child came with either no name or a pseudonym, its token was also kept in the file. Children’s looks change, but their tokens kept faith. The tokens we see today are mainly from children who were never reclaimed.

Some mothers clipped off a swatch from their clothes or their infants’ rags as identifiers. The Foundling Museum’s collection of swatches is the finest collection of eighteenth-century textiles in the world, particularly of cotton prints worn by the poor. All told, the tokens mean this was not cynical, selfish child abandonment. It was abandonment in hope. In hope of care and nutrition. And in hope of education for the girls to become housemaids, and for the boys to become sailors.

The exhibit looked at items of material culture that are small, but bighearted. It’s not fine architecture or good silver. It’s us. Dickens understood that:

I shall not ask you on behalf of these children to observe how good they are, how pretty they are, how clever they are, how promising they are, whose beauty they most resemble—I shall only ask you to observe how weak they are, and how like death they are!

Michael Olmert is a professor in the English Department at the University of Maryland. His article “On Garden Mounts” appeared in the summer 2014 journal. Special thanks to Stephanie Chapman, of the Foundling Museum, London; Harold Gill, of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (retired); and Jean Russo, of the Maryland Archives.