Old Muddy James and the Flow of History

by Dennis Montgomery

Historic Jamestown Island today, on the banks of the James River, site of the first permanent English settlement in the New World in 1607.

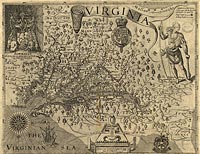

Taken from Captain John Smith’s “Generall Historie,” his map shows the James River and “James-towne.”

Today a historical marker gives notice to Pace's Paines and Indian, Chanco, who saved Jamestown settlers from a 1622 massacre.

Fort Monroe today on the James River, a fortress surrounded by a moat, has withstood foes and the elements since 1610.

Library of Congress

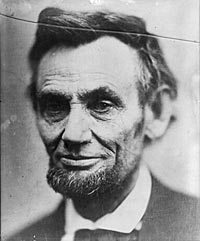

Abraham Lincoln landed on the banks of the James River in 1865 and visited fallen Richmond. The same year, photographer Alexander Gardner took this photo, traditionally called the “last photograph of Lincoln from life.”

Library of Congress

A 1905 photo of the Monument to Confederate Dead in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery, which stands on the north bluff of the James. Not far from the pyramid are the graves of rebel soldiers who died at Gettysburg, and were reinterred at Hollywood after the war.

First settlers found the river "navigable upp into the country deepe" and teeming with "sweete Fishe as no mans fourtune hath ever possessed the like"

The timeless tides of history water the valley of the old muddy James. Steady as the rise and retreat of the sea that besets it, the currents of the national saga flood and drain the broad, shallow stream, etching meanders in the chronicles of a country, inscribing passages in the epic of America. Adventure, discovery, and conquest; massacre, revolution, and rebellion—blood spilled in them all has mingled with the James.

Likewise the sweat of nationbuilding.

On this river Englishmen established their first permanent New World settlement, cultivated one of their empire's richest colonies, helped fashion it into a nation, and led it to independence. Eighty-five years later in the watershed of the James their heirs determined the question of that nation's indivisibility.

In the basin of the James historic sites scatter down byways traced before Captain John Smith trod them—asphalted Indian footpaths blazed by roadside tablets. My car flashes past them, bound for the river, the workday dawn, and the Jamestown ferry. These woods and swamps were once the hunting grounds of the vanished tribe called Quiyoughcohannock.

Jamestown, the first fasthold of Englishmen on this continent. Jamestown, the paradigm of privation, disease, and death.

An amalgam of fossil sandbars, the Jamestown isthmus was a Paspahegh possession when the colonists set up fort-keeping. They chose it for seclusion, defense, and the nearness of the channel.

On June 22, 1607, Captain Christopher Newport left 104 men and boys to their fortunes and sailed for England and supplies. By the end of the year all but 38 had died. Men succumbed to fevers, fluxes, swellings, arrows, and dissension. Mortality sometimes reached 80 percent. Graves quickly outnumbered living inhabitants, and sometimes even the survivors dwelt in holes in the ground.

A week before there was a Jamestown the Quiyoughcohannock welcomed the luckless English to their south shore village. Fashioned of sticks, vines, and leaves, the Indian settlement huddled somewhere near the brick ranch house my clan shares today on a James River bluff at Claremont.

The tribe's principal man, perhaps the werowance Chippoke, led a boat's party up a steep, sandy hill—a bank like the one above our family's childstrewn summer cabin. Colonist George Percy said the werowance "met them, playing on a flute of a reed, with a crowne of Deeres haire colored red, fashioned like a Rose, with a chaine of Beads about his necke, and Bracelets of Pearle hanging at his eares, in each eare a birds claw; of a modest-proud behauiour." He took them to town and "entertained us in good humanitie."

No doubt they shared venison from the forest, corn pone from the gardens, and clams and oysters from the vast beds of the shallow rich river. Perhaps some caviar, too.

From time to time an archaeologist in-law turns up Quiyoughcohannock bones at our neighborhood 17th-century manor, a relic of the tobacco plantation that had supplanted the aboriginals' huts by 1621. A few years back he unearthed a ring of skulls long ago secreted for a purpose now more obscure than the sound of the lost tribe's name. It's KEY-yo-ko-han-knock. It seems to have meant "gull river place," a reference to the fat, brown creek that here joins the James.

The first time I sounded out those syllables Dwight D. Eisenhower was President, and I had landed a job—my first—at a summer camp on the old tribal land. It was work in the river itself, teaching Boy Scouts how to swim.

Boy and man, the river has summoned me back. I've come by thumb, bus, automobile, and airplane from wherever life has led me. Come to court a country girl, to sail, to tent, to write, to work, to live. Back to the ragged loblolly, to the groundhog skedaddling through the peanut fields, to the surly Dark Swamp snapping turtle, to a Sunken Meadow copperhead coiled by a gum stump.

The bends of the James beckon with whispers of the past that bespeak present prospects of natural beauty. Whitetails browse a pine barren. A fog bank ghosts by on a flat-black current. Sipping morning's first cup of coffee on the cabin porch, we meditate on a great blue heron stalking the shallows by the cypress. High above my sun-swamped canoe, two bald eagles scrap over a fresh-caught fish.

By the first ship home, the English wrote: "We are sett downe 80 miles wthin a River, for breadth sweetness of water, length navigable upp into the country deepe and bold channel so stored wth Sturgion and other sweete Fishe as no mans fourtune hath ever possessed the like. And as wee thincke if more maie be wished in a River it will be founde."

For them the James began where it ends, at the bottom of the Chesapeake, below a point they named for the deep-water ease of a commodious anchorage. Percy wrote: "We came with our ships to Cape Comfort; where we saw five savages running on the shore." It was April 30, 1607, fifth day of their landfall.

For a fortnight the human stock of the Virginia Company of London--tradesmen, second-sons, and castoffs—plied the river dreaming of gold and of getting rich quick. They feasted with the tribes their coming doomed: Kecoughtan, Paspahegh, Chickahominy, Appomattuck...

The naturals called the watercourse after their emperor, Powhatan. The English named it the Kings; then, less ambiguously, after England's monarch, James His River.

Seven days after disembarking to build James Fort, one-armed Captain Newport took 23 men upriver to look for the Northwest Passage. On an island below an impassable jumble of granite rapids, they came about, and raised a cross. Mystified Indians watched. Their village is lost now in the streets of Richmond.

Noses in the early editions of the Richmond newspaper, the rural Surry County commuters on the ferry rarely glance at the river isthmus where English America began. A granite obelisk pokes out of Jamestown's trees. On the rip-rapped shore below, the ostentatious statue of the vainglorious Smith catches a shaft of the sun in the new morning damp above Lower Point.

Downstream to starboard and around a bend opens Burwell Bay. Smith bartered there for Warrascoyack corn in 1608. That December at Jamestown maid Anne Burras married carpenter John Laydon—the first Christian nuptials in English-America. Farther below, off Mulberry Island, chance forestalled a bid to abandon infant Virginia in 1610.

It was the spring after the Starving Time, a narrow winter of graverobbing cannibalism. As the survivors fell downriver for home they met an unexpected resupply fleet, and turned back, cursing.

At Buoy 55 the ferry swings to port and bends upriver in the wake of legends. President Abraham Lincoln came close by here aboard the River Queen in 1865. Answering the summons of General Ulysses S. Grant to the City Point headquarters of the Army of the Potomac, he spent the last weeks of the war anchored where the Appomattox marches into the James.

The confluence of the James and Appomattox is as good a spot as any to scoop into the sediments of history the river has laid down. Here in the environs of modern Hopewell, Newport's expedition paused at an Appomattuck village. Queen Opusoquinuske entertained.

Four years later, Sir Thomas Dale ejected her and staked Bermuda Hundred on the peninsula the rivers make. At its western limit he built Henricus, a seven-acre settlement intended to supplant Jamestown. His tools were the lash, rack, and noose. Draconian laws terrorized workmen into industry—if Indians didn't get them first.

Nemattanew tried. A warrior-magician, he boasted invulnerability to bullets, and costumed himself as a bird. He ambushed the column of laborers sent to build Henricus, tearing at its flanks as it hobbled upriver, and he became a favorite of Opechancanough, Powhatan's treacherous son.

War was persistent, if episodic, until Captain Samuel Argall kidnapped one of Powhatan's daughters. Her name was Matoaka, though the English called her Pocahontas. That was a fatherly term of endearment that translates roughly to "little wanton." Confined to Henricus in 1614, the Reverend Alexander Whittaker made her Virginia's first convert, christened her Rebecca, and married her to John Rolfe of adjacent Varina.

The Peace of Pocahontas began. Rolfe and his princess lived on his James River plantation until they embarked for England in 1616. She met the queen, impressed the preachers, amused the curiosity seekers, and shipped for home. At Gravesend, before clearing the Thames, she died.

In 1618 the London Company chartered the University of Henricus to civilize recalcitrant savages. Income from a Falling Creek bloomery—America's first iron foundry—was earmarked for the institution. The company set aside lands and laborers for support, Londoners donated money, and George Thorpe, formerly of Parliament, came over for its deputy.

The English doubted the wisdom of drinking water. Thorpe discovered how to distill spirits from maize—the first corn whiskey--and he busied himself otherwise befriending Indians.

On the bluff at the Appomattox's mouth, the colonists had established Bermuda City—later City Point. They intended a free school to prepare Henricus scholars. In their preparations they paused to elect two burgesses to the General Assembly of 1619—the first meeting of a representative, American legislature. Indian affairs dominated the session. Pocahontas was dead two years, her father one, Opechancanough ruled, and relations were unsteady. They got worse.

Two English servants slew Nemattanew in 1621. Opechancanough feigned unconcern, and plotted revenge. Groups of unarmed braves innocently drifted into the dispersed James River settlements March 22, 1622.

"And by this meanes that fatall Friday morning," a London screed said, "there fell under the bloudy and barbarous hands of that perfidious and inhumane people, contrary to all lawes of God and men, of Nature & Nations, three hundred forty seuen men, women, and children, most by their owne weapons; and not being content with taking away life alone, they fell after againe upon the dead, making as well as they could, a fresh murder, defacing, dragging, and mangling the dead carkasses into many pieces, and carryiung some parts away in derision, with base and brutish triumph."

Five died at City Point, six at Henricus, 17 at Bermuda Hundred, all 27 at the iron works. Indians killed 11 at Berkeley Hundred, hacking Thorpe apart with particular ferocity.

Jamestown escaped.

Chanco, an Indian servant, betrayed the plan. He was a denizen of Pace's Paines, Richard Pace's plantation in the Quiyoughcohannock country opposite the town. It's on the way to the ferry. The night before the massacre a warrior stole in to enlist Chanco in the attack. Instead the servant warned his master.

After seeing to the safety of his family, Pace put his boat in the James and rowed in the dark across to the colony's capital. At the 11th hour, Jamestown stood to its guard. Indians approaching the palisade saw the preparation and withdrew to the forest.

A merciless campaign of English retribution followed the attack; this time no one counted bodies. George Sandys, treasurer of the colony and the author of the first book written in English-America, went against the Gull River Place.

The ferry must cross Pace's track to the settlers' paltry bastion. In most of its renditions the fort was a tinderbox, no bigger than a house lot in Williamsburg, the city that replaced Jamestown in 1699. The notion of historicity did not attach to the compound in time to preserve the spot, or the memory of its location, before the eroding river washed it away.

At Scotland Wharf, on the river's south shore, the ferry's cement and steel landing aims vaguely toward the longsubmerged site. If anything is left of the beginnings of English-America, it is now haunted by the blue crabs and catfish that browse the river's bottom.

Some of the great James River plantation homes have proven more durable landmarks. The easternmost of the surviving mansions, Carter's Grove, reigns atop a terraced lawn on a bluff. It was built about 1753 on what was Martin's Hundred. Wolstenholme Towne was the hundred's administrative center. Staggered in the Massacre of 1622, it slipped into oblivion. A Colonial Williamsburg archaeological team led by Ivor Noel Hume unearthed it and some hatcheted victims in 1976.

What led them to their deaths was what would bring so many men and women to America—the hope of better lives.

Explorers looked up the James for the way to the Orient—and better livings—wandering into its tributaries, establishing plantations, laying out towns. As much a system as a stream, the James is the central vein in a network of capillaries and arteries that service the land.

Governor Alexander Spotswood led a party of gentlemen over the Blue Ridge past what they mistook for the river's headwaters, Swift Run, in 1716. To each explorer Spotswood gave a horseshoe pin of gold.

It took years more to gain the James's northernmost source, a silvery creek on the east slope of Jack Mountain above today's Doe Hill. Over the summit, toward Possum Trot, gather the Potomac's headwaters. The nameless run that would be the James sparkles down an Appalachian ravine strewn with cobbles and discarded bed springs. It cuts across a chestnutrailed sheepfold, recruits two brooks, and gashes the Bullpasture River on the valley floor. The Bullpasture joins the Calfpasture to sire the Cowpasture.

Above the Bluegrass Valley, the Jackson splashes off Lantz Mountain and spills south, filled by highland rushes. Falling Spring, a humble tributary, hurls itself 200 feet over a rock, and curtains a mosscovered cliff. To Thomas Jefferson's eyes this was Virginia's only remarkable cascade. For a time "Mad Ann" Bailey had the sight to herself. Widowed by Indians in 1774, she outfitted with men's clothes and weapons, then set out for scalps. For a year she holed up at the fall.

The Jackson and Cowpasture meet outside Iron Gate and slip into a bed of timesmoothed stones beneath a limestone bluff. Here the river first is labeled James. It loops out of the Appalachians, spits across the Valley of Virginia, and gropes over the Blue Ridge, slicing free at Balcony Falls. Careering through the reddirt Piedmont, it probes the land for soft parts, falling across scattered rapids a foot or two a mile.

Born in a 2,000-foot tumble down Pinnacle Ridge, the Tye fattens the James below Bent Creek, slowing its pace. In the corn-and-cattle midlands a row of trees traces each bank, doublescoring the river's sentences as it scribbles southeast. At Richmond the James makes sea level with an exclamation point, coursing down seven miles of boulders.

The lower James follows a valley flooded 9,000 years ago by the ocean. Each century the water inches upward half a foot. Twice a day it leaps. Slugs of sea tug up on the moon—thus the term Tidewater. They flow in on the north and leave on south, eroding ancient seabeds full of marl and the fist-size teeth of extinct sharks longer than nightmares.

The river's width ranges toward six miles in Hampton Roads, its depth to 85 feet off Bachelor's Point above Brandon. But the averages are 3.75 miles and a yard. At low tide on a hot summer day I can walk 100 yards into the river at Claremont before I get my chin wet. Every foot is muddy; near Carter's Grove an ounce of dirt clouds every 77 gallons.

Washing through Hampton Roads, 340 miles to its credit, the river spends itself in the Bay. Its watershed, largest in Virginia, drains 10,000 square miles—a quarter of the state and half its past.

Musket shot off Old Point Comfort at the end of the Roads the black sail of a nuclear submarine steals silently off the slate gray bay in the fiery fusion of a rising sun. All but awash, her hull radiates lazy ripples as she slips toward Norfolk. They roil down the beach where Newport grounded his shallop and feasted with the stoneage bowmen Percy saw running on shore.

The ironclads Monitor and Virginia brought modern naval warfare to the world in 1862, just upriver there to the right. A pier straddles the place where prisoner-President Jefferson Davis, suspected of plotting Lincoln's assassination, landed for two years' confinement in 63-acre Fort Monroe.

Nearby, 250 years before, captive Africans first stood on English-American soil. The only account is a by-the-way in a 1619 letter written by Rolfe. His tobacco experiments had given Virginia a cash crop, riches, and an appetite for labor. "About the latter end of August," he wrote, "a Dutch man of Warr of the burden of 160 tunes arrived at Point Comfort, the Commandors name Capt Jope. . . . He brought not any thing but 20 and odd Negroes, wch the Governor and Cape Marchant bought for victualls (whereof he was in greate need as he prtended) at the best and easyest rate they could."

Spanish-American War cannon guard the ramparts of Fort Monroe, the largest enclosed fortification in America. The first fort, Algernon, stood here in 1610. No place in America has been fortified longer.

On the James's south shore, Norfolk sprawls up the tributary Elizabeth River. Homesteaded in 1632, Norfolk became a 50-acre town in 1680. By 1765 it boasted 400 homes and was Virginia's busiest port.

Across Hampton Roads is the home of modern America's biggest shipyard, Newport News. Called Point Hope by 1619, it offered a spring where vessels stopped to water. How it came by its present name is a point of some uncertainty. By one account Newport comes from the captain; News from intelligence brought by ships calling at the spring. By another reckoning, the moniker is the corruption of the name of two 17th-century shipbuilding brothers named Neuce. They had built, but abandoned, a port in Ireland to start a new one here. New Port Neuce. Trouble is, Irish records harbor no Port Neuce.

Smithfield, across the James and up the Pagan, also served sailors. Perhaps by coincidence, the rafters of nearby St. Luke's mimic the ribs of a ship. Though they date to 1887, the brick walls beneath may have been laid in 1632. That would make the church America's oldest.

Tradition holds Blackbeard once hid in the Pagan. Other tars called for provisions, including pork well-preserved for sea. Known now around the world, salted Smithfield hams were exported as early as 1779.

Watermen's boats moor in that sluggish stream, the worn white and gray craft of men who work at the end of oyster tongs. The dark waters wind through mud flats teeming with frogs and box turtles, buzzing with mayflies and mud daubers. The first English to paddle up College Creek must have seen much the same things, though rather more of them. Fish ran so thick, they said, a man could walk across a stream on their backs. At the head of this rambling run the settlers had by 1633 set up Middle Plantation along a ridgebound horsepath that divides the watersheds of the James and York.

Here, 66 years later, Governor Francis Nicholson laid out Williamsburg, named after William III. It became the political, economic, and cultural center of England's best possession. At least until 1775 when John Murray, Lord Dunmore, ordered marines from the James to seize the powder in the Magazine on Market Square. Soon, he, too, stole away. Troops dispatched from Williamsburg won Virginia's first Revolutionary War battle, defeating Dunmore's forces December 9 at Great Bridge. The first day of the new year he bombarded nextdoor Norfolk. One of his cannon balls hangs high in a wall at St. Paul's Church downtown.

In 1780 Jefferson contrived to move the capital to Richmond. Thus Williamsburg slid into somnambulance. Nearly a century and a half later, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., awakened it to its 18th-century grace and took up part-time residence himself.

Jamestown struggled along as a port, ferry landing, and plantation. General Charles Cornwallis moved his troops there July 4, 1781, to ambush the Marquis de Lafayette. In September troops from Admiral De Grasse's fleet landed, bound for Yorktown. Confederate earthworks dot the island, their rear guarded by the Back River.

It spills into the bend dominated by Hog Island, a peninsula the settlers used for a pig pen. There at the Devil's Woodyard freeholders gathered in 1673 for America's first taxpayers' revolt. Arrested, the "Company of Giddy Headed and Turbulent persons" were accused of riot. Hog Island is now the preserve of a nuclear power plant.

Through the heart of plantation country the James winds past landmarks of its tobacco-money heydays. At Berkeley Hundred on December 4, 1619, Captain John Woodlief and 38 colonists came ashore with orders that the day "be yearly and perpetually kept holy." They conducted a service of thanksgiving, arguably English-America's first. The Pilgrims did not sail from England until September 6, 1620.

Berkeley is the birthplace of Benjamin Harrison, signer of the Declaration, and of President William Henry Harrison. To amble up its sweeping lawn from the river is to walk in Lincoln's footsteps. Twice the President came to Berkeley to confront the contentious General George McClellan.

"Little Mac" retreated to the plantation from Malvern Hill, the final engagement of the Seven Days battle and his only win. Three times on July 1, 1862, Rebels charged Yankee batteries supported by gunboats in the James. They fell in waves. McClellan recoiled from victory, Colonel William Averell guarded the withdrawal. Of the morning he wrote: "Over five thousand dead and wounded men were on the ground in every attitude of distress. A third of them were dead or dying, but enough were alive and moving to give the field a singular crawling effect."

Waiting to evacuate, General Dan Butterfield and bugler Oliver Wilcox Norton that summer composed "Taps." Confederates heard the air and echoed it across the James. Berkeley slept, abandoned, for 75 years until Union drummer boy John Jamieson returned and bought it in 1905.

Greenway is birthplace of the 10th president, John Tyler. He lived later next door at Sherwood Forest.

Though its manor has not survived, Flowerdew attracts visitors to its rich archaeological sites. Indians occupied it by 9,000 B.C., and it was the seat of Governor Yeardley who, to grind corn, built the first EnglishAmerican windmill in 1621.

Evelynton dates to the 1930s but is a representation of a colonial home Yankees destroyed. Then it was owned by Edmund Ruffin, Jr. His father fired the first shot at Fort Sumter. Bluecoats salted Evelynton's fields and girdled its trees.

Benedict Arnold burned Wakefield across the river but spared neighboring 17th-century Claremont Manor, where in 1861 lived the richest man in Virginia—measured in slaves.

Brandon ranges the adjoining shore. John Martin, who sailed with Sir Francis Drake, patented it in 1610. Exempt from Jamestown's rule, it was the refuge of Virginia's riff-raff. Martin died in 1632, the last of the 1607 settlers still in Virginia.

Upstream, Shirley remains in the hands of the original family, the Carters. A formal house from the early 1700s marks a tract settled by 1613. About 1650 Thomas Stegge II built nearby Belle Air.

The river twists toward Dutch Gap, a cut-off Union soldiers dug to shorten the route to Richmond. When it became Virginia's capital, it was a scruffy town of 684 souls and but two houses of brick. Until Stegge opened a trading post in 1637, Falls settlements came to naught. Stegge's son left the family's holdings to his 18-year-old nephew, William Byrd I, in 1670. Byrd's son turned it into a community, but debt forced William Byrd III out in 1756. Modern downtown sold at a Williamsburg lottery in 1768. George Washington bought 568.5 acres. Thomas Jefferson drew the streets.

The Second Virginia Convention met March 20, 1775, at St. John's Church. Patrick Henry rallied his countrymen from the uncertainty of fear to the fervor of armed rebellion, declaiming "give me liberty or give me death." Benedict Arnold took the town without a fight in 1781. The British stayed long enough to destroy the Westham Foundry, a source of Continental arms.

Masons laid the Capitol's cornerstone in 1785. From Paris, Ambassador Jefferson sent a model of a Roman temple to imitate. It stands today by the front door. Down the hall, John Marshall acquitted Aaron Burr of treason in 1807. A life-size bronze stands at attention where Robert E. Lee accepted command of the Army of Northern Virginia. But the building is dominated by a marble Houdon modeled in life on the frame of the great Washington.

Richmond became the South's industrial powerhouse. Amid the river wharves crowded flour mills, ironworks, printing plants, tobacco factories, and warehouses. To carry goods to the interior and raw materials out, in 1764 the legislature authorized construction of America's first commercial canal. It chartered the James River Navigation Company in 1784. Washington became its president.

On March 21, 1861, Jefferson's temple became the Capitol of the Confederacy. A tobacco warehouse became notorious Libby Prison; Belle Isle Prison opened on an island Smith bought from Indians.

Below, at Rockett's, Lincoln landed in 1865 to stroll the Confederacy's fallen capital, thronged by rejoicefully just-free blacks. He visited President Davis's house, sat at his desk, went to see the wife of one George Pickett, and accepted a wet kiss from her baby. Pickett, of Gettysburg fame, was with Lee on the road to Appomattox Courthouse. Before reboarding his flagship, Lincoln inspected Jefferson's temple.

West of town on a secluded river cliff Jefferson Davis rests beneath a bronze statue gazing for eternity at the headstone of a man named Grant. A little north a rough-hewn pile of stone rises in a pinched pyramid over 18,000 Southern dead.

Tuckahoe's Gates open on Jefferson country. The plantation belonged to their Randolph relatives, and Thomas attended school there with his cousins with his cousins. Tobacco barons patented Piedmont estates by the 1680s. The Jeffersons took up claims, too. Thomas's grandfather, Isham Randolph, built Dungeness about 1730. Among Goochland County records are the marriage bonds of Thomas's parents, Peter and Jane, and a deed for his birthplace, Shadwell. Testifying to the hospitality of a Williamsburg innkeeper, it conveys the farm "for and in consideration of Henry Wetherburn's biggest bowl of Arrack punch."

Twenty miles west of the Falls, William Byrd I led 120 French Huguenot refugees to Manakin in 1700. One discovered outcroppings of coal. By 1750, the town was center of Dover bituminous operations, America's first successful coal business.

At the Point of Fork, the James meets the Rivanna, the way to Monticello, James Monroe's Ash Lawn, and the University of Virginia. Red-coats chased militia from the confluence in 1781, and General Phil Sheridan's raiders struck Confederates here in 1865. Today the point stands abandoned, a narrow, steep peninsula down a rutted dirt road where boys fish in the shade of cottonwoods.

Scottsville was what Charlottesville became, county seat and the region's commercial hub. From here to Lynchburg, the James works a countryside of sleepy towns. At Hatton ferrymen still pole travelers across the James on a raft tethered to a cable.

The river turns to parallel the rising Blue Ridge. Clouds gather on the flanks of Brushy Mountain in a stand of timber never cut except by nature.

Lynchburg is the river's last approach to a city. The town tumbles down the south bank into a flat of factories. It began with 17-year-old John Lynch's ferry in 1757. He built a tobacco warehouse on the bank and lowered hogsheads by rope to bateaux. Flat-bottomed 40-foot craft poled by three slaves, the rough-hewn bateaux set out through the rapids for market. Striding up and down on walk-boards port and starboard, leaning on poles probing the gravelly bottom, they pushed downriver through the Virginia heat, seeking the shade of the tree-lined banks.

Jefferson had a hideaway in the neighborhood. He built octagonal Poplar Forest to which, in retirement, he escaped from Monticello callers to play with his grandchildren.

It is uphill to Glasgow, an 1890 attempt at town building. The James cleaves Buchanan, a town founded in 1811 and the terminus of the canal. Between it and the source, only fishermen and Eagle Rock—crowned by the stacks of four defunct lime kilns—interrupt the river.

So the James ends where it begins, the Jackson coming down Rainbow Ridge on the left, the Cowpasture past a straggle of sycamores on the right.

Sprawled aboard a sailboat anchored far downstream, lazing in the sticky heat, the sun low on the bank above me, the cool mountain scene floats up in my memory. Cattle wade at the edge. A squadron of ducks quacks in circles. On the flood plain crouch three homes, red-brick ranchers like the one I live in, with carports and pick-up trucks. On the lawn is the still-wet hide of a just-skinned buck. A penned dog barks and leaps. Automobiles and 18-wheelers course through a curve on the two-lane blacktop, scattering gravel into of a clump of aluminum mailboxes.

The river gathers itself and pushes on, flowing away through time, off through space, washing the past with the present, pouring forever into the future.

Colonial Williamsburg Journal Vol. 15 No. 1 (Autumn 1992) p. 48.